In the darkness of London’s Casino Cinerama, a 21-year-old David Bowie stared at the space embryo floating across the theatre’s huge, 70mm screen. It was summer 1968, and this was the third time the singer-songwriter had been to see 2001: A Space Odyssey, released in April that year.

“It was the sense of isolation I related to,” Bowie told Classic Rock in 2012. “I found the whole thing amazing. I was out of my gourd, very stoned when I went to see it – several times – and it was really a revelation to me. It got the song flowing.”

While Stanley Kubrick’s film provided the setting and title for Bowie’s first Top 10 hit, Space Oddity, there were other inspirations shaping the song’s sound and vision. That summer, Bowie was hooked on Simon & Garfunkel’s Bookends album – especially Old Friends, whose breezy chords he borrowed for the ‘tin can’ section of his song. More significant was the downward spiral of Bowie’s relationship with his actress girlfriend Hermione Farthingale.

“It was Hermione who got me writing for and on a specific person,” Bowie said. The break-up would yield a handful of songs, but the lonely void that Bowie felt in her absence found its perfect metaphor in the marooned space capsule of Major Tom.

While Bowie has never commented on the origin of his astronaut’s name, there is one intriguing theory. As a kid growing up in Bromley, he saw posters advertising the well-known music hall performer Tom Major (Prime Minister John’s dad), and the name lodged in his brain.

Whatever the source, Major Tom became the first in a long line of mythical characters to float through Bowie’s musical universe (and one who would return in 1980’s hit Ashes To Ashes).

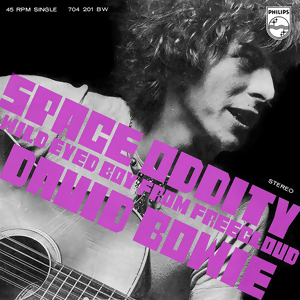

With the song’s neatly designed, rocket-like structure in place – it had seven distinct sections, as opposed to the three or four of most hits – Bowie recorded a demo in late 1968 for the short promotional film Love You Till Tuesday. That version, thin and reedy, with Bowie mimicking the spaceship sounds himself, failed to make commercial waves. But it got him signed to Mercury Records. With that mission accomplished, the first order of business was to record a proper, full-on version. Bowie assumed that he’d be working with his friend and producer Tony Visconti. But Visconti hated the song, calling it “a cheap shot – a gimmick to cash in on the moonshot”. Into the breach leapt Visconti’s young engineer Gus Dudgeon.

“In those days a gimmick was a big deal and people who had gimmicks were taken more seriously than those who hadn’t,” Dudgeon has said. “Bowie’s was that he’d written a song about being in space at a time when the first US moonshot was about to take place. I listened to the demo and thought it was incredible. I couldn’t believe that Tony didn’t want to do it.” Recorded on June 20, 1969 at Trident studio in London, the track was plotted out with the precision of a space launch.

From the well-timed entrances of Herbie Flowers’ bass and Rick Wakeman’s Mellotron, to the controlled chaos of the lift-off and the spooky distress calls dotting the outro, the clever arrangement propelled the song into an atmosphere far beyond the demo. The song’s majesty is even more remarkable when you consider the session costs were under £500. Dudgeon mixed the track in stereo, which was almost unheard of for radio singles at the time.

It was rush-released on July 11, nine days ahead of the Apollo 11 Moon landing. Copies were air-mailed to US disc jockeys. But despite the efforts to piggyback on NASA’s moment of glory, it got little play in the States. The reception in England was much warmer, however.

“It was picked up by British television and used as the background music for the landing itself in Britain,” Bowie said, then added with a chuckle: “Though I’m sure they really weren’t listening to the lyric at all; it wasn’t a pleasant thing to juxtapose against a moon landing. Of course, I was overjoyed that they did. Obviously, some BBC official said: ‘Right, then. That space song, Major Tom…’ blah blah blah, ‘That’ll be great.’ Nobody had the heart to tell the producer: ‘Um… but he gets stranded in space, sir.’”

“I don’t think it was like anything anybody had done before, and that’s why the record is still a classic.”

Gus Dudgeon

Space Oddity remains Bowie biggest-selling single in the UK and his signature song. It won an Ivor Novello Award in 1969. And although there were a few commercial bumps in the years following, it was kind of a scouting mission for the worldwide fame that would come in 1972 with the extraterrestrial Ziggy Stardust.

A theatrical set piece of his live set, Bowie used to sing Space Oddity while being lowered by a hydraulic lift into a giant hand. The song has been covered by more than 20 artists, including Def Leppard, Tangerine Dream and Cat Power, and featured in the videogame Rock Band 3. In 1979 Bowie recorded a stark version of it for BBC TV’s The Kenny Everett Show and performed it inside a padded cell.

Intergalactic lullaby, break-up tune, NASA tie-in, Space Oddity is all this and more. A five-minute, wildly inventive story song which began Bowie’s fertile decade of ground-breaking pop. “I don’t think it was like anything anybody had done before, and that’s why the record is still a classic,” Gus Dudgeon said.

Even Tony Visconti admitted: “I wish I’d dropped my peacenik hippie ideals and recorded this classic track.”

“When I originally wrote about Major Tom,” Bowie said, “I thought I knew all about the great American dream and where it started and where it should stop. Here was the great blast of American technological know-how shoving this guy up into space, but once he gets there he’s not quite sure why he’s there. And that’s where I left him.”

And that’s where he remains, an icon of rock music, and a glittering star in the firmament of Bowie’s legacy.