"I felt a rage towards him that has taken decades to subside": The mysterious case of the fake Fleetwood Mac

Critically acclaimed and loved by their contemporaries, Stretch were perhaps doomed from the start by their involvement in one of the strangest chapters in music history

“Where the hell is he?” York College, York, Pennsylvania, USA, 22 January 1974, and Fleetwood Mac are waiting for an important member of their band to arrive: Mick Fleetwood. The drummer is the only original member in this latest version of the group that has been re-modelled by manager Clifford Davis and the rest of the band are getting increasingly uneasy. Singer Elmer Gantry (a veteran of the London scene) and up-coming guitar hero Kirby Gregory (who had been in Curved Air and played sessions with Phil Lynott, Brian Eno and John Kongos) are ready for their first Mac gig, but Mick is nowhere to be seen.

Convinced that they may face an audience riot and legal action if they don’t appear, the group reluctantly go on-stage with deputy drummer Craig Collinge. Assured that Mick will appear each time, they play two more concerts and arrive in New York City for a show at the Academy of Music. Again they are told that the drummer won’t be appearing. During the long break following support acts Silverhead and Kiss, New York promoter Howard Stein and manager Clifford Davis argue. Davis tells him that this is Fleetwood Mac – that he put the group together and owns the name.

It is only then that Elmer and Kirby realise how this is starting to look. To miss one gig was unfortunate. To miss two, a nasty coinicidence. But four?! With a ‘Fleetwood-free’ band growing ever-more mutinous and a restless audience to deal with, an exasperated Davis heads towards the crowd, takes a mic, walks calmly to centre stage and declares: “I am Fleetwood Mac!”

Elmer recalls, “It didn’t feel right and we didn’t know who to trust. We’d started to hear that there were claims being made in the media that we were a bunch of nobodies trying to steal the Fleetwood Mac name which was absolutely ridiculous: Kirby and I had already been in the business for years, we’d established our credentials with Velvet Opera, Armada and Curved Air. We had appeared on radio and TV and had released singles and albums - we were far from unknown!”

39 years later, Gantry sits in a London rehearsal room, finally prepared to talk about the incident that cursed his career but inspired Kirby’s most famous song – Stretch’s Why Did You Do It – aimed at Mick Fleetwood. “It’s time this story was corrected so that my great grandchildren don’t end up reading all the old bullshit that’s been peddled unchallenged in the music papers and national press and on TV,” he says.

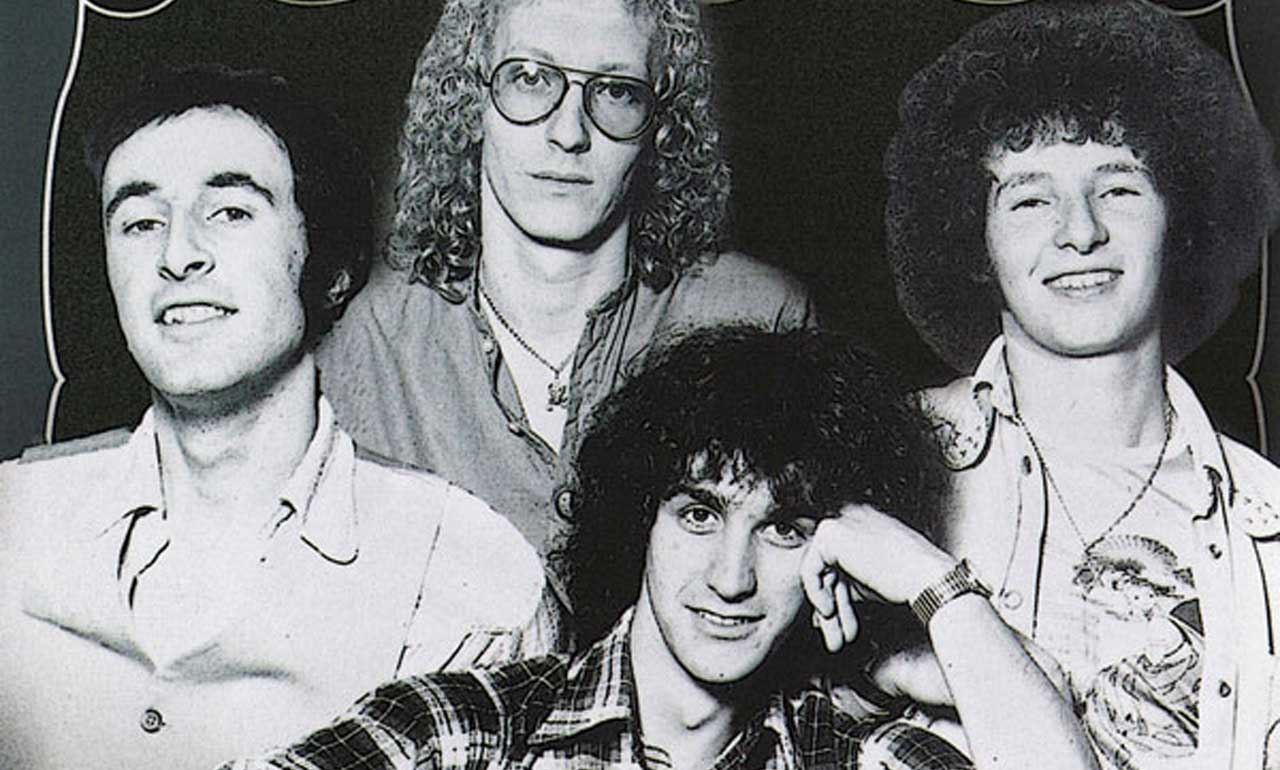

To some, Stretch were one of the finest British blues rock outfits of all time. In January 1976, Sounds earmarked them as a major breakthrough band and proclaimed: “Ol’ Elmer Gantry’s growling vocals and young Kirby’s menacingly tough guitar suggest they may become quite monstrous.” But the road towards the formation of Stretch had commenced much earlier.

Gantry’s musical career began in the early 60s. Inspired by Ray Charles and Howlin’ Wolf, Elmer (known then as Dave), started singing in a variety of upcoming blues groups and guested with Long John Baldry and The Downliners Sect. In 1967 he recorded a ground-breaking album as the vocal and focal point of Elmer Gantry’s Velvet Opera. Inevitably, as the front-man, Dave acquired the nom-de-plume Elmer, probably influenced by his habit of wearing a preacher’s hat and cape. The name Elmer Gantry was taken from a famous 1920s satirical US novel – later a 60s film.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“At first it was fans who called me Elmer, then the band did it to take the piss and it eventually stuck,” says Gantry. Elmer Gantry’s Velvet Opera was once listed among the ‘Top 100 Greatest Psychedelic Albums Of All Time’, while Clash frontman Joe Strummer was a fan of the LP and Elmer’s composition Flames became a UK hit single, covered by Led Zeppelin in their early live sets in 1968.

During this period, Elmer jammed with many musicians including Jimi Hendrix and Jeff Beck. Gantry: “Velvet Opera had a residency at The Speakeasy and all sorts of people would would join in and play. Hendrix was one. He got [Velvet Opera guitarist] Colin Forster’s guitar one night, turned the amp full up and we did a slow blues.

"Jimi then took the axe off and began to hammer a riff with one hand. He held the guitar out into the crowd and Jeff Beck took over while Jimi grabbed John Ford’s bass and we started to jam. Halfway through the number, Eric Burdon stepped up and we finished as a duet. It was a real event. Viv Prince from The Pretty Things got up too but was too ‘tired and emotional’ to stand.”

Following the split from Velvet Opera, Elmer formed The Elmer Gantry Band with bassist Paul Martinez and drummer Johnny Sutton from The Downliners. Stretch guitarist Kirby Gregory meanwhile, influenced initially by Freddie King and Johnny Winter, joined his first pro-band at 17 – the progressively-inclined Armada, featuring world famous reed player Sammy Rimington and bassist Rik Kenton, later of Roxy Music.

Elmer joined the band as vocalist in 1971 and Armada became a popular live act, one of their songs later inspiring the brass arrangement for Why Did You Do It. Rimington recalls: “Elmer had a phenomenal voice and presence and Kirby was amazing for someone so young. He owned a broken Framus guitar and was only able to try out for Armada using a borrowed Telecaster, but you could see Kirby’s ability and incredible potential – he won hands down!”

As a restless 19-year-old, Kirby left Armada in 1972 to join Curved Air, appearing on the album Air Cut. Eight months later however, he and drummer Jim Russell were back playing blues-rock with Elmer. Curved Air manager Clifford Davis held no grudges and placed their first recording, as Legs, with Warner Brothers. But despite critical acclaim and a number one on Time Out’s alternative chart, Elmer’s lyrical reference in So Many Faces to ‘the pigs and the poets’ attracted a stupid ban. Lou Reed sang about ‘givin’ head’ in 1973, but the BBC ignored that, perhaps more worried that Legs might be “insulting the police”.

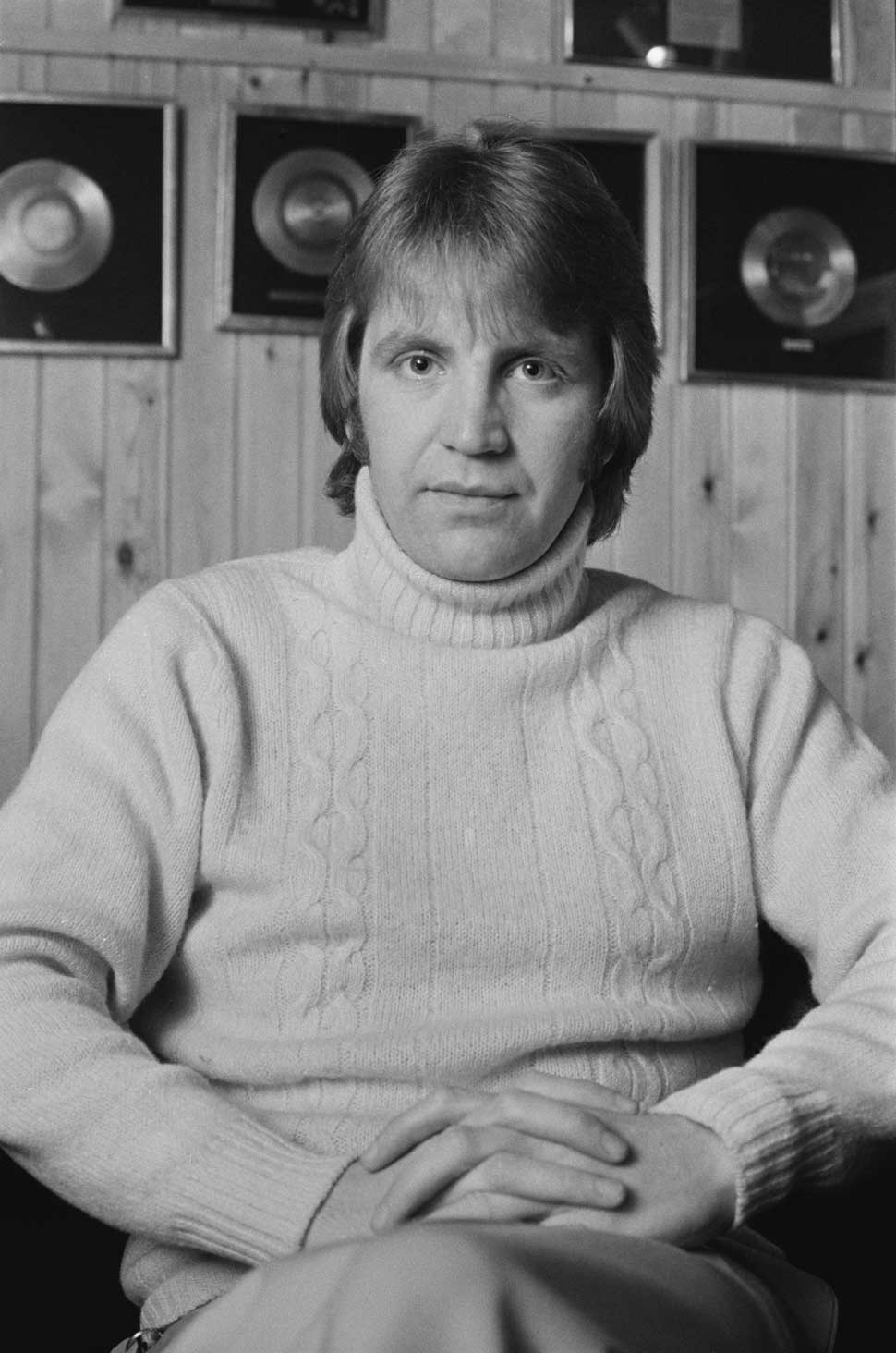

Clifford Davis also managed Fleetwood Mac. The band had lived out a dramatic soap opera of tour cancellations and personnel changes during their early years and, in the middle of yet another US trek in late 1973, Mick Fleetwood discovered that his wife Jenny Boyd (sister of Patti, then the wife of George Harrison) had been having an affair with guitarist Bob Weston. The tour was aborted and Gantry and Gregory claim that in November that year Clifford Davis and Mick Fleetwood invited them to join the fragmented group. Now nearly 40 years on, Elmer finally feels able to give his side of the story.

Gantry explains: “After our Legs single, Clifford suggested to Mick Fleetwood that Kirby and I would be ideal figures to be part of a new formation of Fleetwood Mac”.

According to Elmer and Kirby, Fleetwood met with them at their home to discuss details for an upcoming tour, including the possible line-up and material to be played. Fleetwood later testified that he was “non-committal” to the prospect of joining this new line-up. Whatever the truth, both sides agree that he did not rehearse.

“Mick later asked to be excused rehearsals as he was going through heavy personal issues,” says Gantry, “but he knew the songs inside out and would join at the start of the tour.”

In the event, the tour began and Fleetwood was still nowhere to be seen. “For a while we believed that Mick would show,” Gantry continues. “However, when he never appeared and we were later branded in the press as imposters, I felt a rage towards him that has taken decades to subside – even slightly. We desperately wanted out, but we were convinced that we had to do the gigs or end up in court in the States, so we carried on.

“We were receiving encores and ovations, but it felt bad. I thought: ‘What’s the point? This has no future’. Kirby and I were getting really depressed and stoned all the time. We even sacked the pianist on stage one night as he was too drunk to play. Two gigs later, mercifully, Cliff pulled the plug.”

In the end, the ‘New’ Fleetwood Mac played around 15 gigs in the States. The band felt bitterly betrayed, but bassist Paul Martinez has some fond memories: “The US live dates were great because we were a tight band and against all the odds we still managed to play some really good shows. Joe Walsh told me at one gig in Florida that despite Mick Fleetwood not being there, he thought we were rockin’ with the best of ’em. I don’t recall any major hostility towards us either. Elmer and I just thought: ‘We are stuck with this so let’s make the most of it’ – and we gave it all we had.”

Eventually legal action was brought between the original Fleetwood Mac and their manager. “Last year I saw details of a 1974 Fleetwood Mac versus Clifford Davis court case which were extremely interesting,” says Gantry. “I also saw Mick’s book Fleetwood [1990] at the same time. In his biography he wrote that he didn’t even know our names, but that I contacted him years later to apologise. Total bollocks!”

In his book, Fleetwood commented, “To this day, I don’t know the names of the musicians involved and I don’t wanna know,” a fact contradicted by 1974 court documents in which the judge noted: “on 13 November, as the plaintiff’s own evidence discloses, the plaintiff Fleetwood alone went to see the third and fourth defendants [Gantry and Gregory] and discussed the position and did not object”.

“If Mick had at any point said to us that he had changed his mind, or simply didn’t want to do it, we would never have gone to the States,” says Gantry. “I don’t know what his motives were and I’m not going to guess, but I can say, despite all the lurid claims, we never were required to go to court. Davis split with the original band of course, and I believe an ‘accommodation’ was reached. Cliff certainly didn’t seem to be any poorer for the experience.”

Paul Martinez has his own take: “I think Mick Fleetwood, in a moment of despair over his wife’s infidelity, agreed to do something that he later regretted, and to save face with his fellow bandmates he denied having made any agreement. It’s regrettable that he was not man enough to admit his mistake and come clean with everyone. So as far as I am concerned, he not only lost his wife, he lost his honour too – not to mention his hair!”

Gantry, Kirby and Martinez felt emotionally drained and damaged by the Mac debacle, but forming Stretch in 1975 with Jim Russell, they recorded Why Did You Do It, which tore into Mick Fleetwood – and several international charts.

Kirby: “The line that says: ‘The only ones who know the truth/Man that’s him, me and you,’ was about the fact that me, Elmer and Mick sat in our Tooting flat and discussed the new Fleetwood Mac.” Stretch’s debut album Elastique, produced by Martin Rushent, was also a classy disc, encompassing blues, hard rock, funk and folk. Elmer: “We recorded at Rushent’s first home studio, in the garage under his house. It was full of second-hand eight-track equipment that was all fairly knackered, but Martin got a fantastic sound for us. He was such a tremendous engineer and we were hoping to continue working with him, but Martin also had a major falling out with Cliff and it didn’t materialise.

“It took me some time to get the measure of Clifford because I had viewed him, like us, as one of the victims of the Mac situation. It wasn’t until the initial success and excitement had died down a bit, that I began to have serious doubts.”

Why Did You Do It hit No.16 in the UK singles chart and was Rushent’s first Top 20 record. The band even made a stunning promotional film for Why Did You Do It with director Bruce Gowers in the same month that he shot Queen’s Bohemian Rhapsody, both projects employing multi-layered and cascading screen imagery. While the Queen video launched them on the path to worldwide success, the Stretch promo never even got aired. What Kirby describes as “a typical Stretch management-record company faux-pas” meant that the film was completed after the single had peaked and had begun moving down the chart.

In the US, journalists were praising Stretch’s debut album, including Guerin Wilkinson in the Michigan Free Press who hailed them as “the best new rock band I’ve heard all year”, and Elastique as “a masterpiece of mean, funky rock and roll”. Instead of touring the USA however, label and management had Stretch playing Birmingham, Brentwood and Bury St Edmunds. Melody Maker described the excitement that Stretch captured on record as extraordinary.

But while the group thought that the diversity of songs on Elastique was an artistic asset, audiences were confused. Kirby: “The album sounded like three completely different bands. We thought that was good until Why Did You Do It was a hit and everyone expected everything we played to sound the same. In hindsight, the album seemed a bit schizoid.”

Engaging former Armada bassist Steve Emery and drummer Jeff Rich, the band recorded You Can’t Beat Your Brain For Entertainment, a more blues and boogie-based album, but their next 45, That’s The Way The Wind Blows missed the chart. Kirby: “People believed that song was from a completely different group after our debut single, but we never were a funk band and didn’t want to become one.”

In 1976 Stretch joined Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow Rising world tour, taking plaudits away from the headlining act. Brian Harrigan heaped praise on Stretch in his Melody Maker review: “Stretch in my opinion blew Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow off the stage when the two bands played at London’s Hammersmith Odeon. They are a summation of what rock music should stand for – tight, sharp, tasty and modern too – with enough class to put them above the other two hundred thousand in that league."

Tony Mitchell also enthused to Sounds readers: “I don’t think anyone expected the band that supported Ritchie Blackmore’s Rainbow to be as good as Stretch were – they were treated very much like the stars of the show. There is little doubt as to the bright future this band should have before them.”

After multiple encores at two Hammersmith Odeon gigs however, Blackmore’s management told Stretch they were “not required” for subsequent European, Australian and Japanese dates and the band was replaced by a fledgling AC/DC.

“I don’t think that Stretch was ever the same after this,” says bassist Steve Emery. “But I think those live reviews had really rubbed too much salt into Blackmore’s wounds.”

Stretch soldiered on with Lifeblood, a fine third album featuring some cover versions that acknowledged their musical influences; DJ John Peel risked upsetting Johnny Winter devotees by describing Stretch’s Rock And Roll Hoochie Coo as the finest version ever recorded when he played the album track on Radio One. The band also remained an explosive prospect live. Brian Faloon, Stiff Little Fingers’ original drummer, reviewing for Sounds music weekly, described a Stretch show in Belfast as “magic”.

Sadly, however, circumstances and management had taken its toll on Stretch. Elmer quit in frustration, Jeff Rich later joined Status Quo and Kirby released a solo album. Gantry: “By the time we were making Lifeblood, I was finished. Kirby and I hardly spoke and I wanted out."

“We became very self-critical in Stretch and ultimately self-destructive,” says Elmer. “I felt in a hopeless, desperate situation and made the mistake of trying to solve this by self-medicating. My rock’n’roll lifestyle, manageable through the 60s and 70s, got more chaotic. I still did occasional sessions and gigs – Alan Parsons, Jon Lord, Cozy Powell and Jimmy Page – but I was getting seriously unwell.

“Then, in 1987 – health gone, veins gone, at death’s door – my wife organised my kidnap into drug rehab. Richard O’Brien [The Rocky Horror Show creator] and Peter Blake [the actor] paid the bill and I survived. I felt scared about re-entering music and it took me a couple of years before I did anything again. I still felt a lot of conditioned negativity about Stretch and the music biz generally. It wasn’t until some years later when Stretch’s BBC sessions were released on CD that I re-listened to some of our material and said: ‘You know what? We really were a great band’.”

Kirby went on to record with Joan Armatrading, Cozy Powell, Graham Bonnett and Gloria Mundi, but Elmer and Kirby’s relationship had fractured. Gantry: “When I realised that I had to get away from Cliff, I handled it badly. I simply stopped writing and withdrew from the creative process. Kirby, on the other hand, was trying to make the best of it and seemed to me to actually be shifting up a gear. We had to split – it was all over. I found out later that Kirby had eventually split from Cliff too and had followed his own downward spiral of depression and self-destruction through the bottle.”

The spirit of Stretch, however, survived through re-issues of Why Did You Do It and the song’s inclusion in the movie Lock, Stock And Two Smoking Barrels. In the early 90s, Elmer and Kirby also reconnected. Bumping into each other at a drug treatment conference in Bristol, they were astonished to find that they had both moved from addiction into addiction counselling.

“We were amazed at the parallel paths we had taken,” says Gantry, “working in senior positions for major rehabilitation organisations. I suppose it’s logical really – we had both given ourselves a real hammering, emotionally and physically. I’d survived the 60s before I met Kirby and was under the impression that drink and drugs were compulsory in the music business. It eventually bit me really badly. Both of us know a lot about self-destruction and a good bit about getting well and we used that knowledge in a new direction.”

The singer and guitarist decided to do a charity performance, ‘for old times’ sake’, but rehearsals were by phone, the soundcheck unexpectedly aborted and they ended up playing the gig without even a run-through.

“It was a real stormer,” says Elmer. ”It felt as if we had never stopped playing together. After that, every couple of years or so, we’d do something together in different line-ups for charity which was both a pleasure and a frustration.”

In 2007, Elmer and Kirby agreed that they had unfinished musical business and Stretch re-united briefly, supporting The Jeff Healey Band with dazzling success. They released a new CD, Unfinished Business, in 2011, featuring re-recordings of Why Did You Do You It and Flames and inventive versions of Live The Life I Love, Down In The Bottom and See That My Grave Is Kept Clean. Gantry: “We’re really pleased with the new album. We picked favourite numbers, including some I did in my first band nearly 50 years ago.”

In the words of former Stretch bassist Paul Martinez (no longer involved with the group): “Unfinished Business is what the Stones could have sounded like had they not been drowned in money.”

Stretch’s legacy continued in 2012 with UK and German live dates and work on an album of new songs. “Stretch reformed because we’ve still got something to say,” says Kirby. “When I was 14, I went to see a John Lee Hooker gig. That night I left with the realisation that there is no age limit to this stuff if you really mean it…"

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock 168, in March 2012.

Campbell Devine is the leading authority on Mott the Hoople and the author of All The Young Dudes : Mott The Hoople & Ian Hunter, the definitive Mott biography as well as Rock'n'Roll Sweepstakes: The Authorised Biography of Ian Hunter. Devine also wrote the liner notes for the posthumous Mick Ronson release Just Like This.