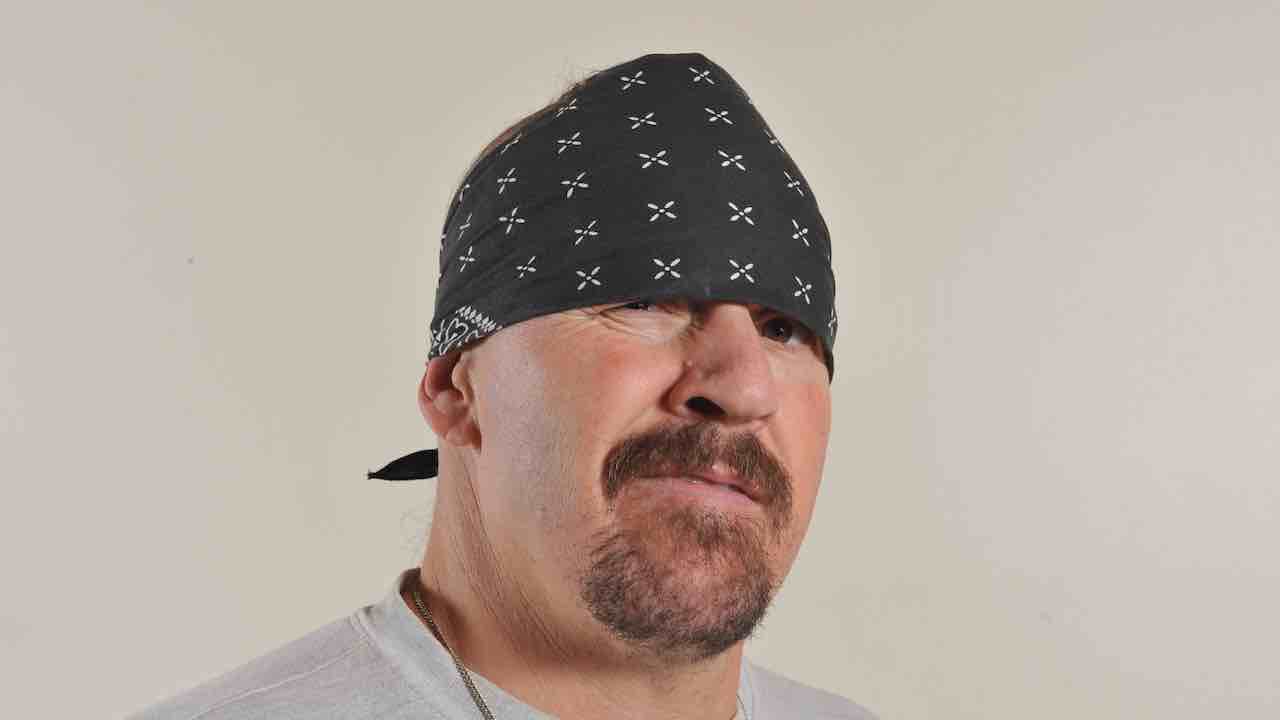

Mike Muir is a hardcore original. The leader of Suicidal Tendencies since they formed in Venice Beach in 1980, he navigated the band through the chaotic LA punk scene to late 80s MTV fame before diversifying into funk-rock with his Infectious Grooves side-project. Here, he looks back on a life less ordinary.

When and where were you born?

“My birth certificate says LA. I take their word for it. There’s a picture of my mom holding an ugly baby in front of the Queen Angels Hospital and that was me. I’ve no reason to think that she tried to trade me. Well, she probably would have but I don’t think she did. And when? I don’t talk about my birthday.”

How would you describe your childhood?

“My parents were always there for me. Sometimes I didn’t think I wanted them to be there, and that’s esteem and it goes a lot deeper. My dad would always go without to make sure we got what we needed, and not what we thought we needed, y’know? I was very fortunate.”

Was the are you grew up in as tough as it seems from the image Suicidal Tendencies has always presented?

“In hindsight, I wouldn’t want my kids to grow up there. But it was a different time and different things went on. We were in the same situation as everybody else so we thought it was normal. I never thought that anything was wrong. Every school year I got a new pair of shoes and a new pair of pants and that was all I needed. I was happy with that. I got to play baseball and do the stuff I wanted.”

- Metallica's James Hetfield: My Life Story

- Testament’s Chuck Billy: My Life Story

- Slayer’s Kerry King: My Life Story

- Ministry’s Al Jourgensen: My Life Story

When did music become important to you?

“When I was probably nine or 10, my brother was 14 or 15 and getting into music, so for Christmas and my birthday he’d give me Black Sabbath and UFO records. Then when I tried to play them, he’d beat me up for playing his records! Ha ha! So I heard music based on what he was listening to and that was good because I bypassed the whole pop thing. People would have the radio on; they’d be singing along and I’d think, ‘Man, this is rubbish!’ The first time I heard some- thing that made me go, ‘Woah! This isn’t like anything I’ve heard!’ was a great experience. When you heard something you liked, it was a special thing.”

Was Suicidal Tendencies your first band?

“Yeah. I moved out from home when I was 16 and lived with my brother and two other guys in Oakland in Venice and we started having rent parties, so we’d charge people and that was how we paid the rent. One of my friends had drums and he lived in this apartment, and his landlord was going to evict him, so we said, ‘Put the drums at our house!’ so he brought them over and everyone was playing them. Then someone said, ‘Dude, I’ve got a guitar!’ and that was it. We started messing around. It wasn’t like starting a band, it was just something fun. We decided to play at one of our parties and charged people more to get in! It went so well that we started renting out halls and doing our own shows.”

Suicidal always seemed to be working class kids from the street. How true to life was that?

“When we started off, a lot of punk rock in the early 80s was just rich kids that were rebelling. It was mostly a white, middle-class kind of thing; people trying to piss off their parents. I got into punk rock because there were no rules, then I realised that everyone that was into punk rock had rules that they expected us to follow; it was a major contradiction. I always said that it doesn’t matter how you dress: do what you believe in and do it for the right reason. Don’t regurgitate what everyone else is doing. People were saying, ‘Dude, you can’t dress that way! It’s not punk rock!’ But we weren’t trying to fit in, we were just doing our thing, and I think that really bothered people.”

Did it surprise you when the band became popular?

“My first experience of that was in LA. They had a commercial station, KROQ, and I was in my car and Suicidal was on and I went to push the cassette out and it wouldn’t come out, and then I realised that it was on the radio! It freaked me out! A couple of days later I was at the 7-Eleven and they had KROQ on and it came on again and I thought everyone was going to say, ‘Turn that shit off!’ but there were a couple of chicks saying, ‘I love that song!’ and it was weird. At the end of the year, we were in KROQ’s top 10 songs of the year, with Culture Club and David Bowie and all that. Strange!”

You existed between punk and thrash. Were you happy being in the middle?

“In the States the word ‘thrash’ didn’t really exist. The punk fanzines said we sucked because we were metal and the metal fanzines said we sucked because we were punk. The first people that really got into us were the people from where we were from and the skaters too. We’d go to a lot of skate contests and you’d hear a lot of Suicidal. It got to the point where we had such a mixture of people at our shows and no one group was dominant, and when you get bigger that way, that really bothers other people too!”

You recruited future Metallica bassist Robert Trujillo in 1989 and began to drift towards the whole funk metal thing that was going on at the time…

“Robert was never into heavy music. A Mexican wasn’t going to hear any really heavy music in Venice, except for Suicidal! There was a debate about whether the bass should be played with fingers or a pick, because that’s what everyone does, but I said, ‘Rob, we’re not everybody! I want you to slap it!’ When that record [1990’s Lights… Camera… Revolution] came out, no one said that it was funk, but when we did Infectious Grooves, everyone started saying it was funk. No one thought Send Me Your Money was funk until Infectious Grooves came out. It’s just that the bass was so prominent and it brought that across more. We took a different approach and added a power to the music that people hadn’t done before.”

Was that the peak of your success?

“In England, we went downhill at that point, but in the rest of the world we went up! But we had Lights Camera Revolution out for nine months and then we went on tour in the US with Queensrÿche. At that time in 1991, Queensrÿche was the most played band on MTV and I heard they were really worried about taking us out! They said, ‘You guys might have to go home!’ Ha ha! But it worked really well and we played 77 shows. The album had been out for nine months, then in a couple of months we sold another 200,000 records with no airplay, no video or anything. It was great to see that if we can play in front of people, a lot of people are gonna like it. Back then we did a lot of stuff and you stopped and thought, ‘Dude, I will always remember this!’ Fortunately there’s been a lot of times like that.”

Suicidal split up briefly in the 1990s. What happened?

“We were opening up for Metallica, playing in front of 20,000 people, and I was absolutely miserable. You walk out at a show and it’s like, ‘I don’t want to be around these people!’ because it’s the people I tried to avoid in school. Someone comes up and goes [adopts annoying shouting voice], ‘Dude! You’re that fuckin’ dude! Fuckin’ A, dude!’ It’s a five-minute conversation like that and I’m thinking, ‘Scotty, beam me up!’, you know? My head’s spinning. This is not what I want to do! The manager would say, ‘The bottom line is, it doesn’t matter as long as you’re selling records!’ and when he said that, a lightbulb went off in my head and I said, ‘You know what? It does matter.’ Sometimes it’s hard, but it’s time to take a step back and re-evaluate everything.”

You seem to do things at a more leisurely pace these days. What made you decide to get off the treadmill and take a more relaxed

“We’ve always said that we don’t want this to be a job. When you’re touring nine months of the year, it’s your life and you sit there going, ‘Is this the life that I really want? Am I really accomplishing something that I think is important?’ and when you’re in that situation there’s going to be many times when you’re sick or something happens and you think, ‘I don’t wanna be here!’ but you’ve just got to do it. We live in our own skewed universe, you know?”

What do you hear when you listen to Institutionalized now? Can you still relate to that teenage kid?

“Definitely. When I was 18 I was going, ‘When I was 16 I was screwed up!’ and when I was 21 I was going, ‘When I was 18 I was screwed up!’ and when I was 25 I was going, ‘When I was 21 I was screwed up!’ I look back and I can say that I’m screwed up now, but not as screwed up! But that first album is a great record and I’m proud of what we did. When we did that record there wasn’t really an audience for what we were doing. Selling 5,000 copies was a big deal. You just did what you did and it was a surprise if anyone else liked it!”

What’s the best thing about being Mike Muir today?

“My dad said a long time ago, ‘If you want to be happy, you’ve got to learn how to say no.’ I learned to say ‘no’ a long time ago, and now people accept it! I think I’ve earned the right to say it and I think that’s great because then when you say yes, it’s a good thing. That’s the best thing for me, feeling in control. That’s not something a lot of people can say. So yeah, I’m happy to be able to say yes and happy to say no. And I wake up the next day and I have no regrets.”

Published in Metal Hammer #205

While you’re here, why not take advantage of our brilliant new subscribers’ offer? Get a digital pay monthly subscription for as little as £1.78 per month and enjoy the world’s best high voltage music journalism delivered direct to your device.