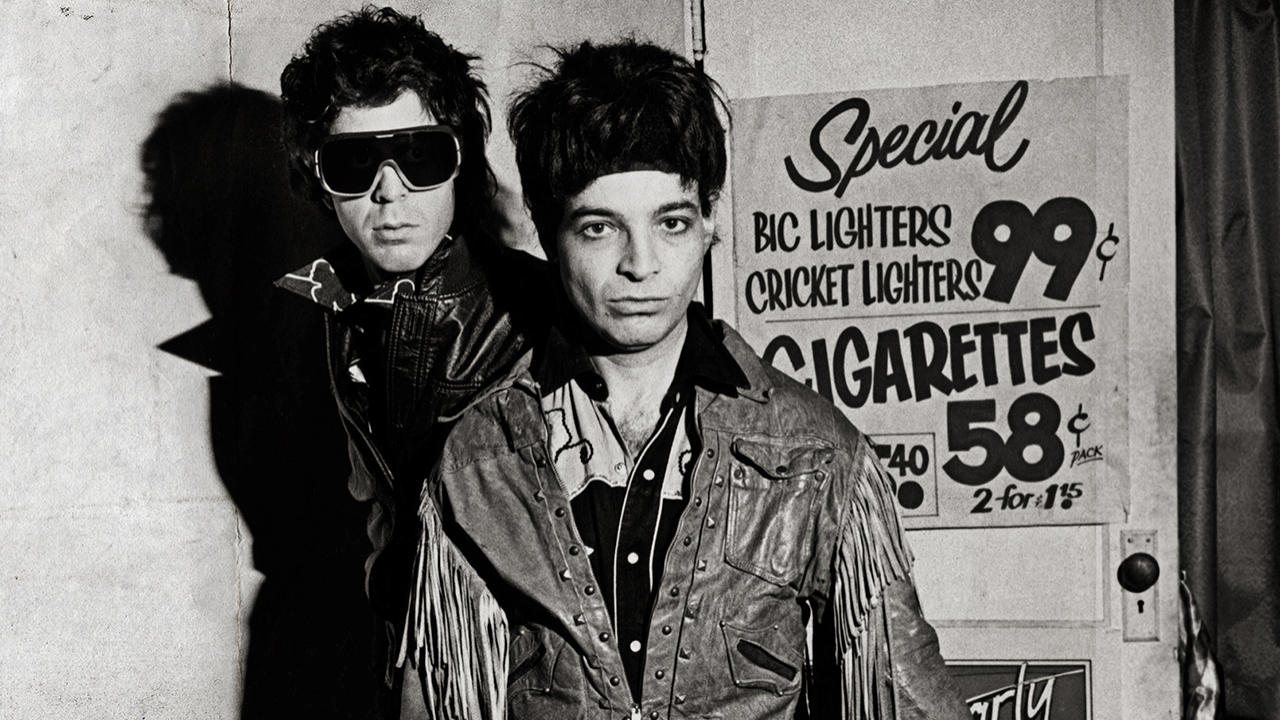

In July 2015, one of the most influential and infamous bands ever to crawl from New York City marked their 45th anniversary with a rare show at London’s Barbican. The high-culture setting was at odds with the fearsome reputation of the two men onstage, singer Alan Vega and instrumentalist Martin Rev.

As Suicide, the duo were a living manifestation of the squalor, paranoia and quest for oblivion that defined America in the 1970s, like the musical equivalent of Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver.

Even set against the punk scene of that crazy decade, Suicide were radicals. Forsaking the traditional guitar-drums-bass set-up in favour of just a voice, keyboard and drum machine, Vega and Rev took the basic elements of rock’n’roll and ripped them apart, then rebuilt them in new shapes. Everything about Suicide was confrontational, from their sound to their antagonistic live shows right down to their name.

“When we started, our philosophy was that the one thing Suicide was never going to do was entertain,” says Alan Vega now. “In those days, audiences wanted to go see a band for entertainment. They came off the street to see us and they got the street thrown right back in their faces.”

“We were living through the realities of war and bringing the war onto the stage,” continues Martin Rev. “It was an expressionistic thing. It was like World Wars Three and Four going on at the same time.”

By the time of the Barbican show, the near-mythical abuse and violence that once greeted Suicide every time they appeared in public had long since given way to admiration and acknowledgement of their influence. They’ve been championed by artists as diverse as Bruce Springsteen, Primal Scream, Henry Rollins, Ric Ocasek of The Cars, Nick Cave, U2 and Ministry, as well as hailed as pioneers of both punk and electronic music. Today, their self-titled debut album stands as one of the most confrontational and groundbreaking records ever made.

Unlike fellow Big Apple trailblazers such as the Velvet Underground, the New York Dolls and the Ramones, this intensely driven duo didn’t fall victim to internal conflicts or debilitating, sometimes fatal, narcotic abuse. And even though Vega, now entering his 78th year, is understandably kicking back after a life-threatening stroke and heart attack nearly four years ago, Suicide remain as indestructible as the cockroaches that still infest their home city.

New York was a different place when Alan Vega – born Boruch Alan Bermowitz – left his wife and factory job in the late 60s to become part of a new artistic enclave gestating in the industrial wasteland of Manhattan’s SoHo District. He became janitor-director at the Project Of Living Artists, a spacious Broadway loft where artists, musicians, poets, radical political groups and street crazies could hang out and express themselves. Vega himself built light sculptures out of abandoned TV sets, fluorescent tube lights, subway lamps and street junk.

Early rock’n’roll and the beat movement had been Vega’s twin inspirations when growing up, but now he was motivated by garage punks ? & The Mysterians, experimental visionaries Can and Silver Apples, and the unfettered expression of free jazz. But it was an explosive show by the Stooges in August 1969 that pushed him towards making his own music.

“What I saw that night was beyond anything I’d seen before,” he recalls. “It was like the new art form because the separation between artist and audience was broken down. “After that night, I thought if I was gonna be a real artist, I had to go where Iggy [Pop] was. I never in my life thought I’d ever get up on a stage. I was totally shy, so it was the scariest place. I had no idea how I was going to make this happen. I can’t perform, much less sing. I must have been out of my mind.”

His early stage performances set the template for what was to come. Joined by a sculptor-turned-guitarist named Paul Liebgott, Vega manipulated tape recordings, tortured electronic circuits and set off wind-up monkey drummers. But it was the arrival of Martin Reverby, of free jazz ensemble Reverend B, that helped take things to a new level. When Reverend B played the Project Of Living Artists in early 1970, Vega was captivated, and joined the band onstage to bang a tambourine.

Vega and Reverby – who would rechristen himself Marty Rev – bonded over a mutual desire to create the loudest, most confrontational musical statement at a time when the anger, protest and invention of the 1960s was giving way to complacency. The name they gave to their new endeavour was inspired by the jazz musicians sitting around the Project shooting smack: Suicide. It was perfect for the times.

“I didn’t see the name in a bad light,” says Vega. “To me, Suicide was a rebirth, a life thing. I was feeling suicidal because of the Vietnam War and how New York was collapsing. It was probably the worst name we could have chosen, but I said, ‘Fuck this shit. What about the Vietnam war? Did you forget about it already?’”

Suicide’s first gig was at the Project in November 1970. Soon they were promoted as ‘Punk Music’, which came from a review of the Stooges’ Fun House by Lester Bangs. The band had also given themselves punk-presaging aliases: Alan was Nasty Cut, Rev was Marty Maniac, Paul was Cool P. “We had no formula with Suicide,” says Rev. “We didn’t start with a beat or instrumentation, but we were going to find it through chiselling out this total mass of sound.”

Rev introduced electronic keyboards in the form of a Wurlitzer piano, setting it up with a snare drum in front of him and playing them both together. This radical approach, together with Vega’s in-your-face stage presence and that name, proved problematic when it came to getting gigs. Their cause wasn’t helped when, during one show, a Brazilian revolutionary group turned up to see them and a riot ensued.

Suicide’s reputation began to spread. Vega was invited to meet his literary hero, poet Allen Ginsberg, only to be attacked by the beat generation figurehead. “All of a sudden he goes, ‘How could you use that word, ‘suicide’?’ and

starts to attack me. I was like, ‘Holy shit, I’m being attacked by Mr Beatnik here!’ Suicide then was so literal, and the reality was death.”

Unable or unwilling to put up with the escalating carnage, Paul Liebgott quit, giving Vega and Rev even more freedom to experiment. Rev acquired a battered Japanese organ for $10, on which he picked out simple garage-punk riffs. ‘Songs’ such as Methedrine Mary, Junkie Jesus and future signature song Rocket USA were built on Rev’s skeletal riffs, which may have sounded other-worldly but were derived from classic rock’n’roll.

“I realised rock’n’roll was the only place that was innately me,” says Rev. “It was also the only place that was still an open frontier. You could still go on stage and do anything, especially with electronics.”

In late 1972, Suicide were playing a residency at the Mercer Arts Center, where the New York Dolls had launched themselves on an unsuspecting public. The two bands sometimes played different rooms in the venue on the same night, leaving the Dolls’ audience to brave Suicide before they could reach the exit. “People were in real fear,” cackles Vega. “The sound alone was so crazy they couldn’t get away fast enough. It was like there was some kind of tornado coming after them.”

Their antagonistic approach made for a memorable spectacle, but it did nothing to endear Suicide to the mainstream music industry. After Rev bought a primitive drum machine from a couple whose daughter had committed suicide, they recorded their first batch of songs at the Project. “We were really starting now,” says Rev. “The carving out process was getting to where there were actual tracks that we could take to record companies to try and get deals. We tried some, but not with any success.”

Even amid the Big Apple’s nascent punk scene, Vega and Rev were outsiders. The soon-to-become iconic CBGB club had opened on the Bowery in late 1973, and Suicide played there for the first time the following summer. But it would be another three years before they were invited back to play there regularly. Vega’s menacing stage presence didn’t help. Rumours spread that he assaulted

his audiences.

“Nobody ever got hurt but me!” he protests. “People often used to recall witnessing stuff I know never happened. I never dragged a woman across the stage. I did used to stop them trying to leave. I used to jump on tables, upset their drinks, but never hurt them. I used to have a knife and chain, and used to cut myself. I’ve still got scars all over the place.”

Suicide’s shows at the NY club Max’s Kansas City gave them a regular audience, but their return to CBGB in February 1977 showed just how much distance there was between them and New York’s punk scene. Vega and Rev had been booked to support the Ramones. Suicide played a fractious set to a crowd of impatient punks who, according to Vega, “booed the shit out of us”. In their dressing room afterwards, CBGB owner Hilly Kristal told them the Ramones had got lost on the way back from another gig and demanded they go back on.

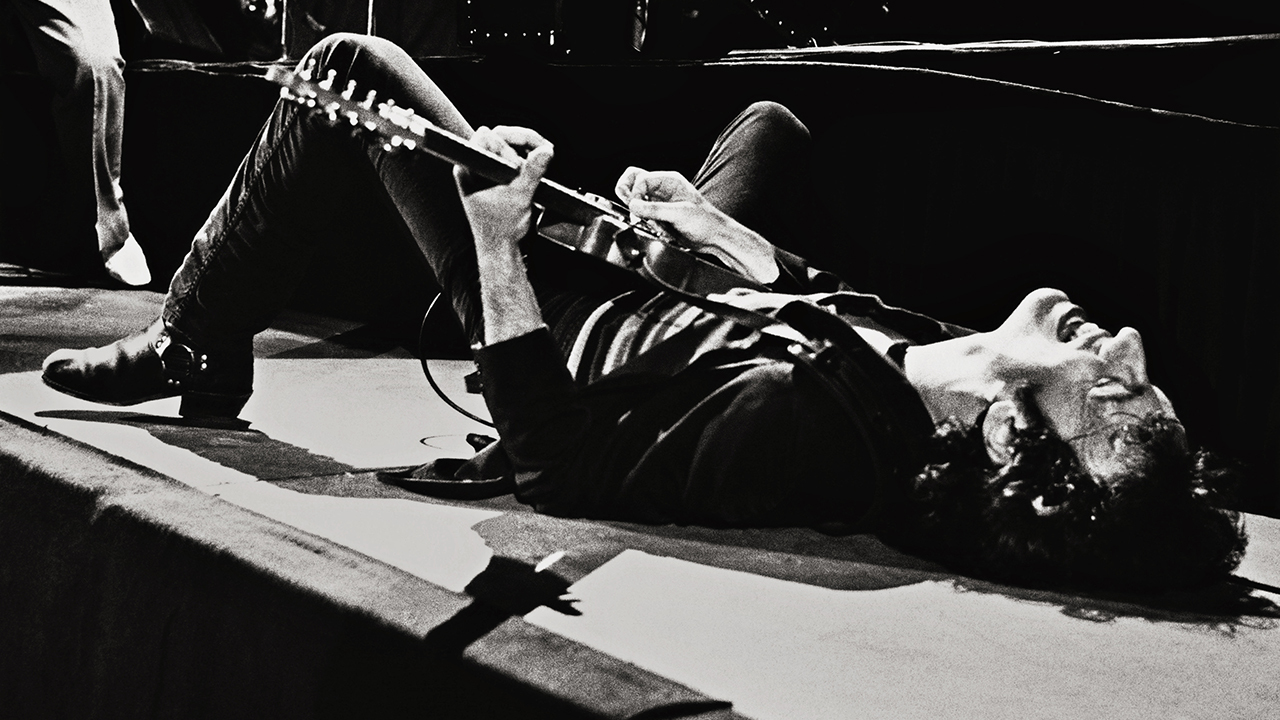

When they reappeared, the booing rose to a crescendo. “I can’t hear you,” taunted Vega, goading the mob with his knife and chain before cutting his own face. The crowd backed off and the booing stopped. People thought he was crazy.

“I’d break a beer bottle, then take a hunk of glass and put it to my face,” he says. “You’re sweating profusely, so the fucking blood would start dripping down and the people in the audience would stop their shit attacking us, man, because they thought, ‘This guy’s insane. He wants to die so let’s leave him alone.’ But you had to know how to do that, man, because it got so bad sometimes.”

By 1977, Suicide were desperate to make an album. Their recorded output to date consisted of a solitary seven-inch and an appearance on the compilation Max’s Kansas City 1976. All around them, punk bands were getting snapped up. “We were the last apples in the fuckin’ barrel,” says Vega.

It was veteran music biz hustler Marty Thau who helped them get their break. Thau had managed the New York Dolls and helped launch the Ramones and Blondie. He heard Rocket USA and instantly saw potential. By June 1977, Thau had signed Suicide to his label, Red Star Records, and booked them into New York’s Ultima Studios to record their debut album with Ramones/Blondie producer Craig Leon.

Leon started by setting up Rev’s ‘Instrument’ (as it’s credited): a Farfisa organ, drum machine, distortion boxes and hooked-in transistor radio. This unique combination of patched-up components played a major part in the album’s alien sound – something only heightened when Thau, in Leon’s absence, decided to mix several tracks himself with a bag of weed for inspiration.

“Marty was trying to explore all the equipment,” says Rev. “Not being a producer, he would push things, not knowing how far he could go. We were getting more and more stoned.”

The resultant album, Suicide, sounded like no other record from New York’s punk scene, or anywhere else. Its seven guitarless songs sounded as arcane as a Robert Johnson blues record while simultaneously mapping out an electronic future. The pulsing speedway joyrides of Rocket USA and Ghost Rider (the latter inspired by the Marvel comic of the same name) were warped inversions of wholesome Americana: Johnny came on like a mutant Elvis and Girl dripped with finger‑clicking alien lust.

But the most notorious track was Frankie Teardrop, a 10-minute onslaught of hopelessness and terror. Originally titled Frankie Teardrop, The Detective Meets The Space Alien, Vega decided to rework it after reading a newspaper story about a factory worker who lost his job and then killed his wife, his kids and himself.

The new lyrics were also inspired by the singer’s own time spent working factory jobs. As the titular character ends it all, Vega lets out a blood‑curdling scream.

“It’s a self-portrait of everybody,” he says. “I almost blacked out with those screams. Putting myself in the guy’s mind was genuinely disturbing. I always think it’s the song Lou Reed wished he would have done.”

Suicide’s debut album was released in the US in December 1977 and in the UK the following July, after being picked up by Bronze Records’ A&R man Howard Thompson. Today, you can hear its blueprint in everything from Depeche Mode to Bruce Springsteen’s pared-back Nebraska. But at the time, it was crucified by the press: Rolling Stone called it “absolutely puerile”. The record-buying public weren’t any more open-minded. DJ John Peel got death threats for playing a track from the album. “We were just singing the new blues,” says Rev, “and the blues scares people.”

“Suicide flew in the face of what was defining punk rock at that time, yet was somehow more disturbing, more threatening and more punk than anybody else,” says Howard Thompson now.

His words were borne out when Suicide supported Elvis Costello in summer 1978. Few, if any, bands have provoked as much vitriol as Vega and Rev did when facing down rock fans enraged by their non-conventional music and appearance.

The trouble kicked off from the moment they set foot onstage at the very first show, at Ancienne Belgique Theatre in Brussels. As Rev started the pulsing rumble of Ghost Rider, Vega began haranguing the crowd. A riot broke out when Elvis Costello was forced to truncate his set after just 10 minutes. “The cops came in with helmets and tear gas,” recalls Vega. “The shit started flying. The cops rioted more than the rioters! I’m laughing my ass off, but the equipment’s getting destroyed.”

Far from being annoyed, Costello loved how Suicide shook up his audience. “One night, we did that real nice, big old place in The Hague [Congresgebouw],” recalls Vega. “The day of the show, I bumped into Elvis walking along the street with his bag of laundry. He goes, ‘Hey Al, do you think you can give us another riot tonight?’ And sure enough they ripped up and knifed the seats in this beautiful symphony hall. The headlines in the newspapers said, ‘Suicide Cause 100,000 Dollars Worth of Damage.’”

Suicide’s stint supporting The Clash the same year was no less eventful. At the Glasgow Apollo, 4,000 Scots reacted to their electronic firestorm by throwing beer cans and worse. “I saw this fucking axe come flying by my head like one of these old cowboy movies,” says Vega.

By the time the Clash tour wound up at London’s Music Machine in late July, Rev was playing behind a Perspex screen, though that was more to protect the ‘Instrument’ from the merciless rain of gob, beer and coins.

When Suicide finally made it back to New York, they were treated like returning heroes. Their elevated standing brought them a deal with a new label, ZE Records, and a new producer, The Cars frontman Ric Ocasek. He helped refine their sonic assault. But like its predecessor, the album – Suicide: Alan Vega And Martin Rev – stiffed, propelling the duo on to separate solo careers. Despite that, Suicide continued to play gigs and sporadically release albums, the most recent being 2002’s harrowing American Supreme.

Alan Vega turned 70 in 2008, a landmark celebrated by the release of a series of EPs of covers of Suicide and solo songs by artists ranging from Primal Scream to superstar fan Bruce Springsteen.

“We were always deemed the least successful band, but we’re still here,” said Vega at the time. “Where are all the other so-called successful bands now? They have their run then they’re gone forever. We’ve gone for the long haul. I’m not going to retire anyway. How can I stop making music? It would be like stopping breathing.”

But in March 2012, he suffered a massive stroke and heart attack, requiring life-saving surgery. “Alan’s a total survivor,” says his long-time partner Liz Lamere. “He should have been dead. But he was sitting there in the hospital going ‘Whadda ya talkin’ about? I’m fine.’ His cardiologist attributes it to very strong force of will.”

In March 2015, Suicide took the stage of New York’s Webster Hall to play their first home-town show in six years. The love that greeted them was a world away from the antagonism of their early gigs. Typically, they didn’t rehearse. The first time the pair saw each other was when they walked onstage from their respective dressing rooms.

“We never do any soundchecks or rehearse,” says Vega. “If I can’t do it now, we’ll never get it right. I showed up and he showed up. It doesn’t matter because Suicide is such a thing now. We can do anything.”

Whether the Barbican gig four months later was the pair’s last performance together remains to be seen. But they can rest assured that Suicide succeeded in their mission to shake up audiences with the sound of the future, even if it did take a few decades.

Dream Baby Dream – Suicide: A New York Story by Kris Needs is out now.

Suicide And Springsteen

“He already knew of us by then,” recalls Marty Rev. “When our album was done, he came into the control room and listened to the whole playback. He came over to me and said, ‘I really like what you guys do.’ He was familiar with us, which was saying something because we’d only had the first album out.”

“Bruce came in and flipped,” Alan Vega remembers. “He liked it right away. I used to hang with him a lot. His manager didn’t want him drinking or anything, but I used to keep a bottle around. It was like kids in school, going to the bathroom to smoke cigarettes. He’s just a great guy.”

Vega adds that Springsteen was particularly gripped by Suicide’s Frankie Teardrop, whose stark sound and blue-collar nightmare influenced 1982’s Nebraska album, notably State Trooper. The mutual admiration continued, with Vega sometimes breaking into Born In The USA at Suicide shows while Bruce closed sets on 2005’s Devils And Dust tour with a hymnal version of the duo’s Dream Baby Dream, performed like a religious mantra on a pump organ.

A recording of one such performance graced the first in a series of 10-inch singles released by Blast First Records to mark Vega’s 70th birthday in 2008. “Bruce is a gentleman and a true fan of Alan’s work,” says label boss Paul Smith. “His office made it very easy to do.”

Vega also recalls going to see Springsteen play Bridgeport, Connecticut that year. “Bruce finished the soundcheck, came over, gave me a bear hug and signed a photo for my son. I hadn’t seen him in over twenty years but it was like the old days all over again. We were talking for an hour or so.” Bruce dedicated Dream Baby Dream to Alan that night. “I’m freaking out! I thought, ‘I’m never gonna do this song the same any more.’ Then the show ends, the lights come up and my song Dujang Prang came on. It’s one of Bruce’s favourite songs. It’s weird shit, but he loves it.”