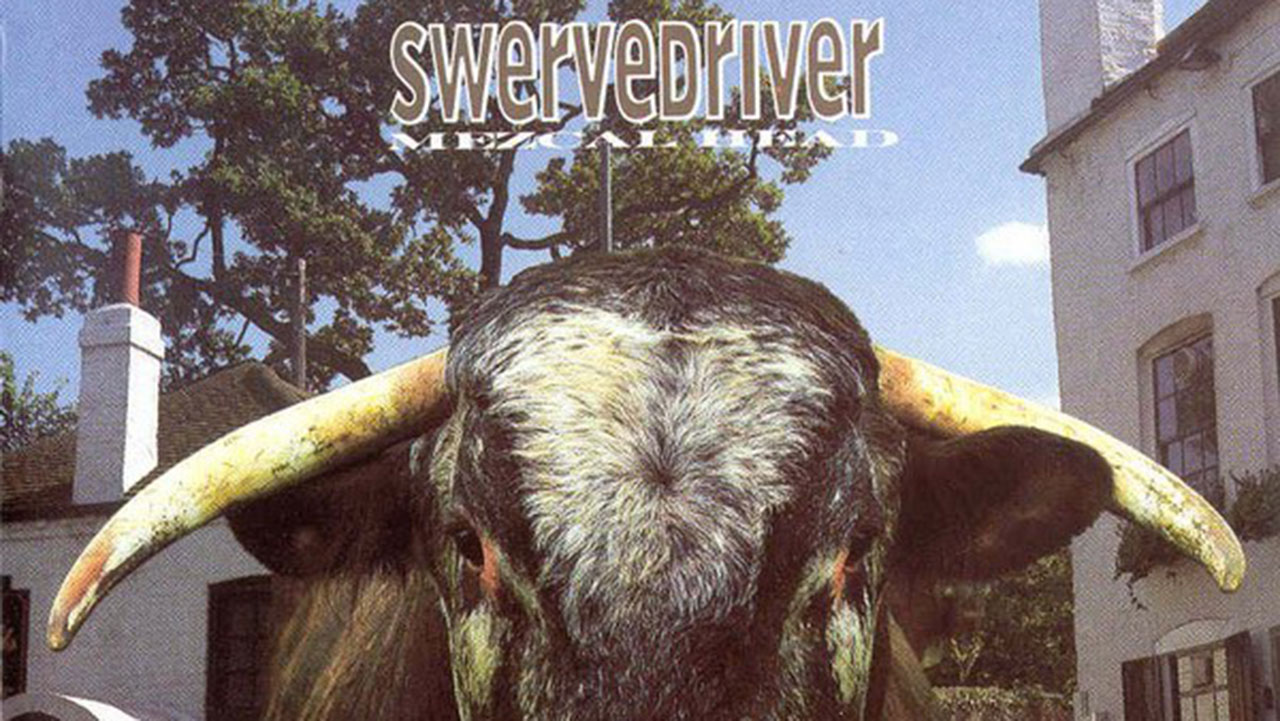

In 1993, Swervedriver created their masterpiece. Following their 1991 debut Raise – an album which loosely drew out a sound hazy and rough around the edges – with Mezcal Head, the Oxford four-piece seized on that sound and distilled it, creating a tight collection of songs which lurched with enough dirgy distortion to hook in fans of the exploding grunge scene, but remained lush and intricate enough to appeal to the dreamers with their eyes locked squarely on their shoes. It would have been an impressive feat by any band’s standard, but it's one made all the more remarkable when you discover that Mezcal Head was an album born from extreme chaos.

“In some ways you could say we were in tatters, because we only really had half a band,” frontman Adam Franklin tells Louder via telephone from his Oxford hometown. He’s recently returned from a stint in LA, and has taken shelter in an abandoned red telephone box to take us through how Mezcal Head came to life, outside an Oxford pub which is, apparently, notorious for its patchy signal.

“[Drummer] Graham Bonnar had left during a US tour, and then [bassist] Adi Vines – who had another band going at the same time called Skyscraper – decided to do that full time, so it was just me and Jimmy [Hartridge, guitarist] for a bit,” he continues. “We were thinking about our next move, because Raise had done pretty good, we'd built up a bit of a reputation in the States, and we'd put in the work – and then we found ourselves with half a band. We'd also lost half our management, so it'd gone from being six people down to three. Basically, we halved in number.”

It was a move which caught the remaining members of the band – and their record labels – off guard. “It was crazy, really,” says Franklin. “For a while, [Creation Records founder] Alan McGee was calling us in the States saying 'What's going on? What's going on?!' because it seemed like the whole band was imploding.” Franklin pauses. “I think it was just the madness of youth. It's great being in a band and putting an album out and you're all 23 and you've never been in the States before – it's exciting. But also, we just couldn't hold it together, I guess.”

But it would take more than a little inter-band turmoil to throw them off course. Thanks to the help of a certain early 90s phenomenon, alternative music was in the rudest health it’d been in before, or since. The record labels involved weren’t about to let another potential chart-smasher go without a fight. “It was also an exciting time, because the labels – Creation in the UK and A&M in the States – just thought we were riding the crest of a wave,” says Franklin. “Raise had gone in the charts the week after Nevermind in 1991. Then Nevermind dropped out, and then Raise dropped out, then Nevermind reappeared massively and changed the whole climate of things. So in a sense it was like, ‘C’mon, let's do this big album!’ So we rebuilt the band with bunch of songs that turned out to be pretty good, to be honest.”

'Pretty good’ turned out to be an understatement. With the new line up came a new creative freedom which allowed the band’s sound to grow, making good on Raise’s robust promise and expanding in every direction. “It was completely liberating, actually,” says Franklin. “We put word out to try and find a drummer and came across Jez Hindmarsh. His drumming style was quite different to Graham's – he's much more a ‘Keith Moon falling down stairs’ drum style. We didn't manage to find a bass player in time, so me and Jimmy figured we could do it. It completely changed everything creatively, because suddenly I was playing bass with Jez on the drums and it was like a new rhythm section. I think it expanded our sound in many ways.”

However, with news of the abrupt line-up re-shuffle spreading, the band were aware they had something to prove, and were wary of pushing Mezcal Head too far from what had come before. “Before Adi had left, at the end of doing Raise, me and Jim had a conversation with him about what we would do with our next album and if we would ‘reinvent ourselves,’” says Franklin. “It's funny, because I remember having a conversation with Damon Albarn down The Underworld one night around a similar time – just as Blur were about to do Modern Life Is Rubbish – and I told him 'We're going to reinvent ourselves.' That was the word back in the day – 'reinvent yourself'. But when it actually came to it, we felt like because those guys had left we needed to reestablish our sound. I think maybe people thought that Adi was the real rocker in the band, so we wanted to have some heavy tunes on there. Then all this stuff emerged that was really great, like Duel and Last Train To Satansville and Duress, so suddenly we were on a new path and it was quite invigorating.

“All those changes made everything feel quite fresh. In hindsight I realised that with all of the Swervedriver albums, there's always been some sort of shift; whether it's been the line up of the band, or the label we were with, it feels like there's always been something that's changed. There's never been two albums where we've actually had that steady situation. In some ways that's good, because it keeps you hot to trot. That was definitely the case here – we were, ‘Okay, those guys have just left the band, they're obviously mad – we're going to do the most awesome record we can do and prove something here.’”

With the line-up cemented, it was time for the band to find a producer. “It was strange early on, around about 1991, when you had people approaching saying ‘We want to produce your record,’” says Franklin. “I think we just got a bit freaked out and we didn't trust people. We had Jamie [Stewart], the bass player from The Cult, who wanted to produce the first album – he was a nice guy, but we weren't sure about that. Then we had the guitar player from Duran Duran – Andy Taylor, I guess – he wanted to produce the first record, too. You'd have people coming up to you in bars or clubs saying ‘Hey you guys should work with me, I'll turn you into stars,’ and that was what we didn't want to hear. We didn't want to have someone trying to turn us into stars.”

Eventually, an opportunity presented itself in the form of indie-rock titan Alan Moulder. “Finally, we met Alan Moulder and that was really great,” says Franklin. “I actually met him at the bar at ULU – we were trying to get served and he leaned across and said 'Aren't you the guy from Swervedriver?' I was like '...Yeah, who are you?' He said, 'My name's Alan Moulder, I produce records.' I [knew of him] because he'd done the Jesus And Mary Chain and My Bloody Valentine records and all that stuff. He said, 'We should work together'. I said, 'I think we should.'

“The Swervedriver sound is always that there's a ton of guitars going on and different textures, and Alan found a way to place all the guitars. Raise was a murky sounding record – it was recorded with our tour manager doing the mixing, because we didn't really trust anybody. But this album had this big production, and we were happy to go with that big production because [it meant] we could really push it and put it on college radio.”

With the producer locked in, the band turned their attention to nailing down the songs. One of Mezcal Head’s most remarkable elements is in its storytelling. With each song, Franklin weaved a compelling narrative dense with imagination, daydreaming and unspecified desires – even when a song’s base material was plucked from the mundane or the everyday. “There was those sort of songs about things that were going on in the news at the time,” says Franklin. “There was a song called Rise Of The Right which I remember having a sit down with Alan Moulder about. He said, ‘You know, these lyrics are quite heavy,’ because it's this whole thing about about the rise of the Neo-Nazis, especially in Eastern Europe. We had this sullen conversation and then Alan said, 'So what's the song going to be called, anyway?' and I said 'Girl On A Motorbike', and he cracked up laughing, because it's like that Spinal Tap thing where he's playing the classical piece of music, then he’s asked 'What are you going to call this?' and he says 'Lick My Love Pump'.

“Last Train To Satansville was based on a song by Marty Robbins called They're Hanging Me Tonight, which was an old country song. It's kind of a re-write of that. There's Harry And Maggie, which is about a friend of mine called Harry Jonas who was a stonemason. The whole second verse of that song literally just fills in the details: he was a stonemason, he got a gig shaping the gargoyles for the Houses Of Parliament, and he carved 'Maggie sucks' on the back of each of them.

“I always saw Blowin’ Cool as being sort of like an Arthur Lee in Love song – it had an LA feel. MM Abduction – which was originally called Mickey Mouse Abduction, but the label were worried Disney would sue us – that story was about someone being in Disneyland and there's a guy in a Mickey Mouse suit who actually who shouldn’t be in a Mickey Mouse suit, some sinister person. Actually I’d just read Brix Smith's biography, and she talks about going to Disneyland in LA as a child, and how there was a Mickey Mouse guy in a suit sending her little love notes and stuff, like ‘Please meet me after work’. So... yeah.

“Certain songs just paint a picture. The first two lines of Duel don't really make sense. It's like, ‘You've been away for so long, you can't ask why’ when really it should be 'I've been away for so long, you can't ask why' or something. But for some reason, that was the line that seemed to phonetically scan and I think ultimately with songs, you just try not to overthink them. For me, I think Duel is still probably the definitive Swervedriver recording. If an alien came down from another planet and asked me, ‘What do you do? Okay, what does your band sound like?’ I'd probably play that song. I just felt that we naturally played this thing where there was suddenly more expanse in the sound. I think because we were trying to maintain our identity from the first album but also push off in a few other directions, we ended up doing quite a well-rounded sounding record.”

With the songs in the can, the time came to promote the record. And – just ask Lennon and McCartney – nothing spurs you on quite like a bit of good, old-fashioned, ex-bandmate rivalry. “When the first single, Duel, was ready to go, it was released the same week as Skyscraper's first single,” says Franklin. “Of course, there was a bit of rivalry, because Adi had left our band and gone to form his band, so it was quite nice that we got Single Of The Week in NME and Melody Maker in the same review session as Skyscraper's single, which didn't get Single Of The Week, because we did.

“When that happened, we suddenly got all this momentum, but it was something like two months before the album came out, so I think there was a sense that we'd lost a bit of momentum [by the time it came out]. So, we went out and did a video off our own back for Duel, and for some reason our manager knew this snowboarder guy who was the world champion snowboarder or something. We flew across to Portland, Oregon, to Mount Hood, and did this video where we're snowboarding down the slopes and just driving around and filming stuff, which was a cool video. But A&M felt that it was too degraded – the actual footage was made to look fucked up a little – and that we had to shoot a second video. So then, at great expense, we went and shot the video in downtown LA, with a catering truck and lots of people working on it – that kind of stuff was weird. We'd just come from two or three years before being a garage band and suddenly you've got all this stuff going on – people being paid to do the lights on the video and stuff. I think we took it all in our stride, really, but it was quite bizarre – you're all sitting in your own little trailer like, ‘Ooh, we must have made it here!’”

They weren’t wrong. While the album was a moderate success in the UK, with the help of a couple of well-timed tours, it blew up in the States. “It was crazy,” says Franklin. “We opened for The Smashing Pumpkins, and that was the first time a lot of people ever heard of us, and we'd done Soundgarden two years before that. There were queues outside the venues every night and people were getting there early to see the opening act, so we ended up playing to already full rooms. That was a massive boot in the arse for the popularity of the band. It's difficult to work out why certain bands are big in some places and not in others, but with our music, it was always about cars and deserts and this kind of wanderlust. That was there right from the start – from right in Oxford in 1989, when we hadn't ever been to the States.

“We'd meet people who'd come up to us after the show who'd say 'Hey, we just drove five hours to come see you play,' and we were just incredulous, like, you drove five hours?! Of course, nobody does that in the UK – you drive five hours and you're in Aberdeen or wherever. People would say things like ‘I play all your songs to be the soundtrack to our roadtrip’. I guess for some reason our music has a connection to the American psyche, even though it's made by four English guys.”

Twenty-five years on, the album has become a benchmark of the alt.rock canon. Frequently name-dropped in ‘top 10’ and ‘best album’ roundups by writers hoping to show they really know their chops, its status as an almost-obscure cult classic is secure. With its 25th birthday looming on the horizon, and having toured Raise in full a few years ago, the band decided it was as good a time as any to celebrate the album’s legacy by taking it on the road. Having completed a North American run at the end of last year, the band are bringing both albums to the UK in May. “It was Jimmy's idea,” says Franklin. “He said, ‘Bands do this now, you do the whole of one or two albums,’ the issue being that it’s a lot of time to be on stage chugging out this stuff. But doing Raise for the first time, there was actually something great about it. I like the fact that it streamlines the whole evening, because people in the crowd, they've come because they like the album, so you know what's coming next. It’s almost a more theatrical performance than a spontaneous show, like going to see a film or something.

“There are certain songs that you never played back in the day – like on Raise, the last song [Lead Me Where You Dare] was never played and there were other songs that were played once or twice, but not really. It's similar for Mezcal Head, where the final track on the UK edition [You Find It Everywhere] we never performed live. That was one song where I like the song, I like the idea of the song – it’s about globalisation – but I felt the lyrics were a bit half-arsed. So when we did it last year, I actually re-wrote the lyrics and a lot of people picked up on that, because they could hear me singing about the President's hair and stuff.

“It's interesting, because there's a worry when bands perform whole albums initially that it's like a museum piece – that it's cast in stone. But of course when you actually get out and play, it literally comes alive. There's a lot of room on both those records for improvisation, like the end of Duel which just goes off in a different direction, and Duress. Every night it just goes wherever it goes. You're quite honoured that you can give this album 25 years and people still want to come and hear it being played. It's a great thing, it comes alive again.”

As they prepare to bring the albums back to UK audiences for the first time in years, how does it feel to look back over three decades of band history? “I'm happy that we're seen to be part of some kind of legacy,” Franklin concludes. “I think there's nothing more that a band could ask for, than to still have people listening 25 years later.”

Swervedriver will tour Raise and Mezcal Head in full in May – check here for full tour dates. Their new album, Remembering Forward, will be released later this year.