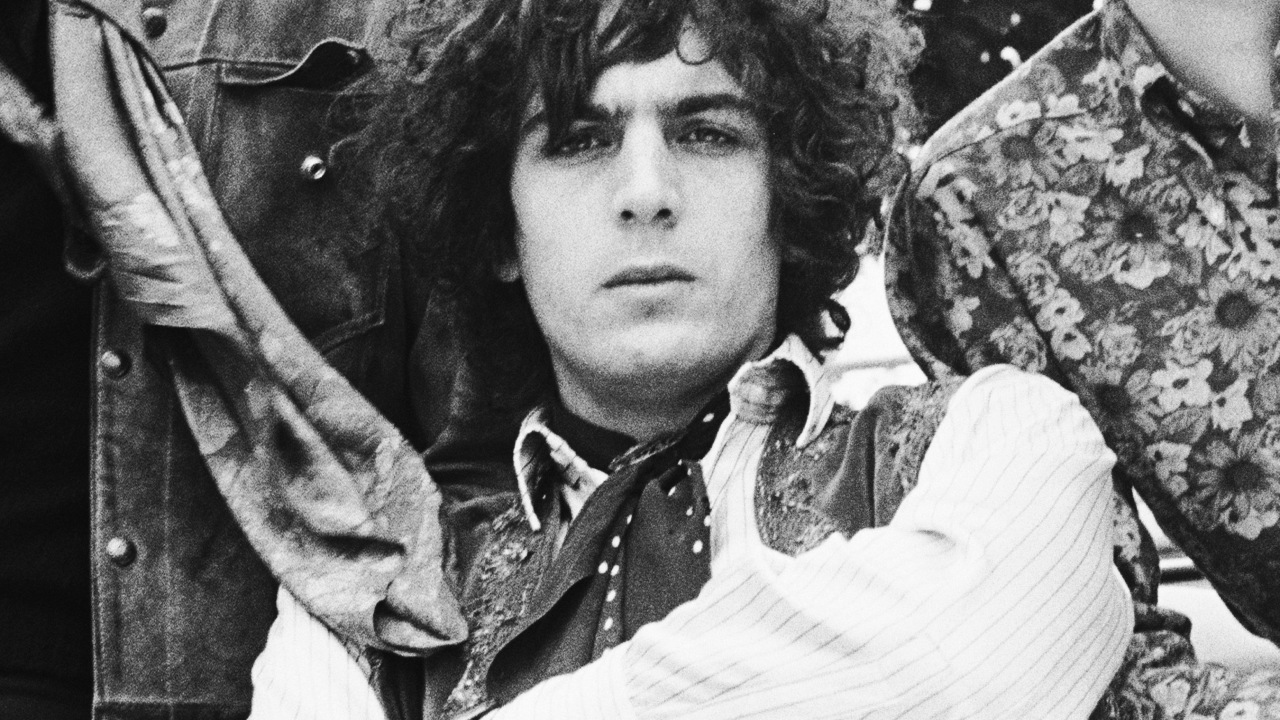

You will no doubt have read the obituaries for Syd Barrett, who died of cancer on July 7 2006. You will have read about how he was the original guiding light of Pink Floyd, who wrote, sang and played guitar on their first hits, including their classic debut album The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn, released at the apex of the Summer Of Love in 1967.

How he was the poster boy for the psychedelic revolution, whose over-fondness for powerful hallucinogens eventually cracked an already fragile psyche – and how the band then dumped him, leaving him to record two extraordinary if appallingly shambolic solo albums, before he disappeared from the scene for ever.

About an exploded star whose legend nonetheless continued to grow with each passing year, becoming both an inspiration for all those who tried to follow in his musical footsteps and a salutary lesson in what drugs can do to anyone foolish enough to abuse them to such horrific lengths, whatever the so-called justification.

But is that really the whole truth about Syd? That he was a musical genius whose madness was simply the flip-side of that enviable talent? The crazy diamond who shined just a little too brightly and whose fall into permanent darkness was somehow justified by the, admittedly highly unusual, albums and handful of singles he left us to pore over? That he was the supreme - in that dreadfully overused phrase - rock’n’roll casualty?

Or was there more to it than that? First and foremost is this idea that Syd was ‘mad’. Although the noted psychiatrist RD Laing – himself an exponent of both LSD and the idea that madness can be an adjunct of genius – once pronounced Syd “incurable” after listening to a tape of him in conversation, Barrett was never officially sectioned. He did, however, spend two years in the early 80s in Greenwoods, a charitable ‘halfway house’ in Essex, where he willingly submitted to group and other forms of therapy, and seemed perfectly happy, say staff – until the day he walked out after a misunderstanding, tramping by foot all the way back to his mother’s house in Cambridge.

Mad, though? Well, he was certainly in poor health for much of his life. But he had never actually been required to take medication specifically for his mental state, except for one uncontrollable fit of rage in the 1980s, when he was taken to Fulbourne psychiatric hospital and given Largactyl to calm him. Indeed, so ferocious were these periodic outbursts that, for a time, his elderly mother, Winifred, moved in with her daughter Rosemary.

But none of Barrett’s family actually considered him mentally ill. There was, however, some speculation as to whether he might have suffered from Asperger’s syndrome, a developmental disorder related to autism. Classic symptoms include difficulty with social interactions and incorrectly interpreting social cues. Asperger’s syndrome sufferers are often highly intelligent too – just unconcerned with anything that doesn’t directly affect them. Certainly, Barrett appears to have lost the ability to interact with other people long before he lost his place in Pink Floyd.

While in later life his best friend appeared to be his local GP, whose surgery is said to have become a second home in Syd’s final years. Again, though, not because of any apparent mental illness, but for the treatment of the diabetes he had been struggling with since the early 90s – and, more recently, for the cancer that eventually killed him. As such he had also become a regular visitor to the private wards of Cambridge’s Adenbrookes Hospital – where a ‘Barrett Room’ is named, not in honour of Syd, but of his late father, the eminent pathologist (and classical music enthusiast) Dr Arthur Max Barrett. After his mother died in 1991, Syd was left largely to his own devices, and was notoriously unreliable at taking his insulin, slipping into diabetic comas from which he recovered only because of the dedicated staff at Adenbrookes.

So what was ailing him, and why did he shun the spotlight so assiduously throughout his later years? Certainly he had not always been that way.

The youngest of three sons and the fourth of five children, Roger Keith Barrett was born at Glisson Road, Cambridge on January 6, 1946. All the family played instruments and Roger was known for his piano duets with his younger sister Rosemary. A good-looking, clearly bright boy who also excelled at art, he was 11 when his father gave him a ukulele.

Following the skiffle boom of the late 50s, he was soon playing his first proper guitar, helped along by his school friend, David Gilmour, a more proficient player who introduced him to the blues.

When, in 1961, Roger began frequenting the local Riverside Jazz Club, regulars jokingly took to calling the handsome schoolboy ‘Sid’, after a much older local drummer named Sid Barrett. By the time he had joined his first semi-pro outfit, Geoff Mott & The Mottoes, he had begun spelling his name ‘Syd’. This apparently idyllic early life came to a shattering end the same year, however, when his father fell seriously ill then died – a blow close friends and family claim Syd never fully recovered from.

Inspired by The Beatles, by 1964 Syd had begun writing his own songs: catchy toe-tappers set to whimsical lyrics inspired by the poems of Edward Lear (especially ‘The Owl & The Pussycat’) and Olde English folk balladry, mixed with the storytelling tradition of grizzled American bluesmen.

However, it wasn’t until he arrived in London, as an art student at Camberwell, that he seriously considered performing his songs in public. Hooking up with old Cambridge chum Roger Waters, then an architectural student at Regent Street Polytechnic and the leader of his own band, The Abdabs (which included fellow students Rick Wright and Nick Mason), it was Syd who suggested they rename themselves the Pink Floyd after two Georgia bluesmen, Pink Anderson and Floyd Council. It was 1965 and within a year their initial mix of old blues and R&B standards had evolved into something much more unusual.

Another of Syd’s old Cambridge pals now living in London, Nigel Gordon, had begun experimenting with phials of liquid lysergic acid diethylamide – known in shorthand as LSD, the new, yet-to-be-criminalised hallucinogen soon to be made famous by such counterculture icons as Timothy Leary and, not least, The Beatles.

“We were all seeking higher elevation and wanted everyone to experience this incredible drug,” Gordon later recalled. “In retrospect, I don’t think [Syd] was equipped to deal with the experience because he was unstable to begin with.”

Unstable or not, Barrett was profoundly moved by his first LSD experiences. His first post-trip composition was a stream-of-consciousness song called Astronomy Domine. According to Storm Thorgerson, another former Cambridge associate who would go on to design most of Pink Floyd’s album covers in the 70s, Syd was “always experimenting” and had “a very open sort of mind, empirical to an almost dangerous degree”.

Although the rest of Floyd were wary, Syd’s involvement with the new drug was a major influence on their musical approach. For example, Interstellar Overdrive was a lengthy, improvisational piece augmented on stage by abstract slide projections and coloured lights. “The musical equivalent of an acid trip,” as Dave Brock, future Hawkwind leader and early Floyd aspirant, recalls.

In 1967 a residency at UFO – London’s first self-avowedly psychedelic club – led to a record deal with EMI. Floyd’s first single, Arnold Layne, was based on the true story of a man who stole clothes from Syd’s mother’s washing line. It received an unofficial ban from the BBC, who deemed it ‘smutty’. “Arnold just happens to dig dressing in women’s clothing,” said a nonplussed Syd. “A lot of people do, so let’s face up to reality.”

Although a minor chart hit, it was their next single, See Emily Play, which put the band into the Top 10 for the first time – and turned the tousle-haired, kohl-eyed Syd into a pop star.

Originally the theme tune for the Games Of May – a ‘happening’ held at the Queen Elizabeth Hall on May 12, 1967 – but reworked at the urging of his managers who smelled a hit, See Emily Play (still featuring its original ‘free games for May’ refrain) was based on Syd’s disapproving view of one Emily Kennet, a 16-year-old UFO regular nicknamed ‘the psychedelic schoolgirl’. Opening line: ‘Emily tries but misunderstands/She’s often inclined to borrow somebody’s dreams/Till tomorrow…’

After it became a hit, Syd moved into an Earls Court flat which Nigel Gordon later described as “the most iniquitous den in all of London”. “Put it this way, you never drank anything round there unless you got it yourself from the tap,” said early Floyd manager Andrew King.

Tripping on acid more or less every day, then using Mandrax (a powerful barbiturate often prescribed as a sleeping pill in the 60s) to help him ‘come down’, it was at this juncture that Barrett first started exhibiting signs of the ‘mental illness’ that would soon derail his career: the long ‘thousand-yard stares’ he treated interlopers to and the sudden mood swings between euphoria and gloom.

Through all this, the band struggled to make their first album. Still lucid at the start, by its end Barrett had become withdrawn and difficult to deal with. “When I look back I wonder how we ever got anything done,” said producer Norman Smith. “Trying to talk to [Syd] was like talking to a brick wall because the face was so expressionless. His lyrics were childlike and he was a child in many ways; up one minute, down the next.”

Released to generally ecstatic reviews, The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn was written almost entirely by Barrett and sounds nothing like the overwrought prog-rock Floyd would begin to play after his departure. Full of references to the ‘trip literature’ of its time (The Gnome was inspired by _Lord Of The Rings _while the album’s title was taken from a chapter in The Wind In The Willows), Syd’s elevated place among the hippy cognoscenti was now assured.

Within a matter of months, however, Barrett’s impossible behaviour had scuppered a US tour (sabotaging a TV appearance on The Pat Boone Show, where Syd simply refused to answer any questions) and ruined several shows closer to home (standing immobile on stage, staring into space, seemingly unable to even play his guitar anymore).

The final straw occurred during rehearsals for Floyd’s second album, when he tried to teach the band a new song called Have You Got It Yet?, which consisted of Syd chanting ‘have you got it yet?’ over an impossibly elaborate chord pattern. As soon as Waters or Wright learned one part, Syd would alter it again, taunting them: “Have you got it yet?”

The upshot: the recruitment in April 1968 of Syd’s school pal Gilmour, initially as fifth member, then full-time replacement. It’s since been popularly imagined that Barrett was so ‘out there’ that he remained indifferent to his ousting from the group. Not so. Insiders tell of Syd initially following the band around in his Mini Cooper, stalking Gilmour who he felt had betrayed him.

By January 1970, however, when Barrett released his first solo album, The Madcap Laughs, he seemed at peace with the situation, happy to promote the album with interviews and completing a session for John Peel’s Top Gear on Radio One. Something of a curate’s egg, whatever gems the album contained (Octopus, Golden Hair) were constantly offset by Barrett’s wilfully erratic singing and playing. Nevertheless, reviews were good, the album spent a week in the UK Top 40, and work began almost immediately on a follow-up.

“It’s quite nice,” Syd said of Madcap… in Beat Instrumental. “But I’d be very surprised if it did anything if I were to drop dead. I don’t think it would stand to be accepted as my last statement. I want to record my next LP before I go on to anything else.”

But Barrett, a similar if even more harrowing confection, released later that year, received only lukewarm praise and by the time he gave his last ever official interview, to Rolling Stone in 1971 – in which Syd declared himself “totally together” – he was already back living in the basement of his mother’s house in Cambridge.

There was one last, aborted attempt at a ‘comeback’, with the trio Stars – also featuring ex-Delivery bassist Jack Monck and Twink, former drummer with the Pretty Things, Pink Fairies and Tomorrow (who Syd knew from UFO days) – but after a bad review of their debut at Cambridge’s Corn Exchange, Syd didn’t turn up for their next gig supporting Kevin Ayers and Nektar at Essex University, and Stars was never heard from again.

After that, there were the occasional sightings… Syd walking around Cambridge in a Crombie jacket, long dress and dirty white plimsolls… Syd walking down the street in his pyjamas… Syd wandering unannounced into a Floyd session as they recorded Shine On You Crazy Diamond, their tribute to him… Syd, fat and bald, mistaken for a Krishna devotee at David Gilmour’s wedding…

One of the more disturbing sightings, rarely mentioned, occurred in 1977, when Gala Pinion, a former girlfriend, says she bumped into him in a supermarket on London’s Fulham Road. They went for a drink, then back to what he claimed was his flat. Pinion told writer Tim Willis: “He dropped his trousers and pulled out his cheque book. ‘How much do you want?’ he asked. ‘Get your knickers down.’” Pinion says she fled, never to see him again.

Fans would continue to make the pilgrimage to Cambridge, camping outside his house hoping for a glimpse of the acid messiah. In the 70s there was a fanzine devoted to all things Barrett, titled Terrapin, but even they got tired of waiting for the Second Coming and eventually gave up. In the 80s, occasionally some fool from the media would knock on Syd’s mother’s door. When radio DJ Nicky Horne tried it Barrett told him: “Syd can’t talk to you now.” Which was true, in the sense that Syd had ‘died’ a long time before – certainly, as far as Roger Barrett was concerned. As he told Rolling Stone in that final interview: “All I ever wanted to do as a kid [was] play guitar properly and jump around. But too many people got in the way.”

- Why losing Syd was the best thing Pink Floyd ever did

- Pink Floyd appear on iconic 60s documentary soundtrack

- The real Syd Barrett – by the people who knew him

A decade before his death, Barrett was reported to be going blind, a side-effect of his diabetes. But again that wasn’t true, although his eyesight did become increasingly ‘tunnelled’ as a result of his indifference to his regime of diabetic medication. Instead, the facts are these. For the last 15 years of his life Syd Barrett lived a mostly peaceful life in Cambridge. His not insubstantial Pink Floyd royalties meant he never needed money, but he did once work for a short time as a gardener at the urging of his mother, who thought he should keep occupied. The only time he visibly splashed out with his money was once, more than 20 years ago, when he booked himself into the Chelsea Cloisters apartment block for a holiday – then decided he didn’t like it and walked all the way back to Cambridge again.

Clearly, he wasn’t what most people would describe as ‘normal’. Talk of his days in Pink Floyd could still apparently bring on severe depressions – which is said to be the main reason why none of the band had any direct contact with him anymore.

There were attempts to resurrect Barrett’s career – everybody from Jimmy Page to Brian Eno is said to have been in touch, while one record company offered £200,000 for “just a few” new Barrett songs – all to no avail. And of course regular Floyd compilations (not least 2001’s Echoes, on which nearly a fifth of the tracks were Barrett originals) and cover versions (most famously, Bowie’s See Emily Play on his 1973 album Pin-Ups) have also helped keep the myth of the ‘crazy diamond’ alive.

What is known is that Barrett spent a lot of time painting, although he had no wish to exhibit. He also collected coins and enjoyed cooking. He had a “very, very ordinary lifestyle”, said his brother-in- law Paul Breen. Contrary to received wisdom, right to the end Barrett was also keenly interested in music. For his 56th birthday, in 2002, his sister Rosemary gave him a new stereo, on which he regularly listened to records by the Stones, Booker T & The MGs and various classical composers.

One group he never enjoyed listening to was Pink Floyd, although when the BBC screened its 2001 Omnibus documentary about him he did watch that. Rosemary said he had enjoyed hearing Emily… again and was especially pleased to see his old landlord Mike Leonard interviewed. Leonard had been his “teacher”, Syd said. Apart from that, though, he’d found it all “a bit noisy”.