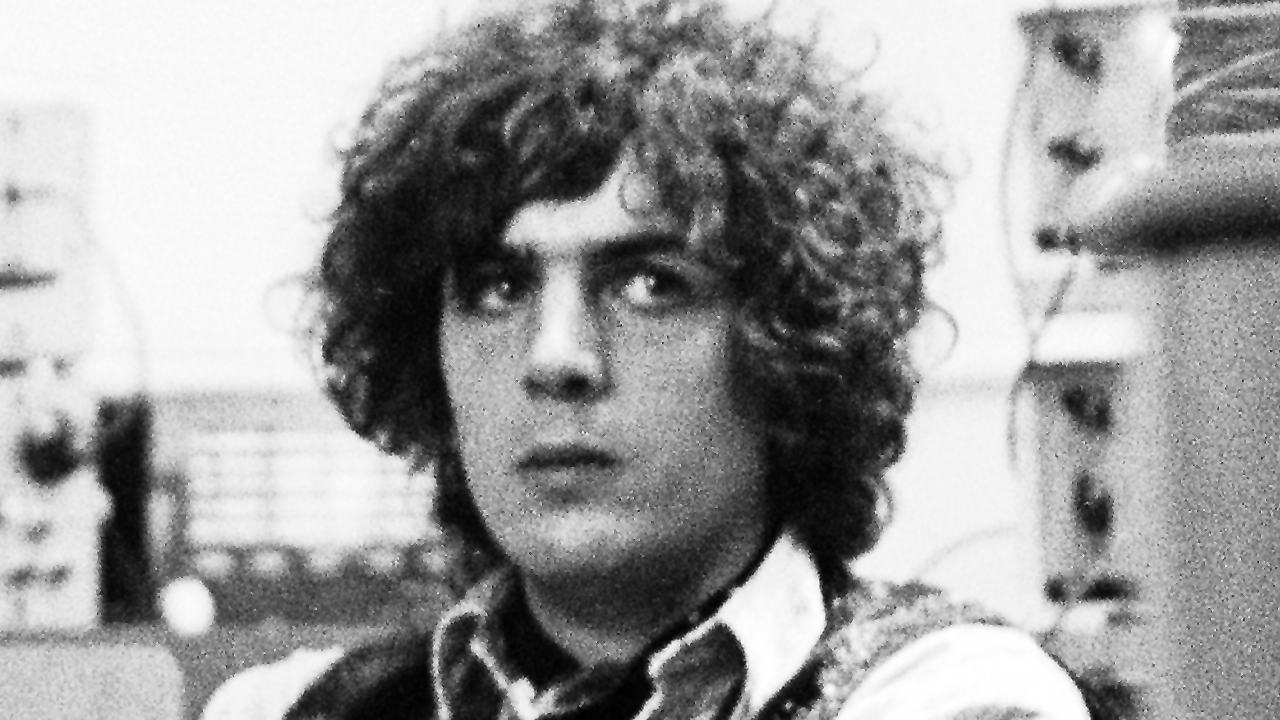

Syd Barrett became something of a mythical creature after his split with Pink Floyd, the band he’d led for its first three years. In 2020 Prog reflected on the wide-ranging legacy he’d left since abandoning the music industry in 1972 and his death in 2006 at the age of 60.

Cambridge, mid-90s: to paraphrase the words of that bloody song by the Television Personalities, we knew where Syd Barrett lived. It wasn’t really very hard to find his house – a few phone calls, a couple of letters and there we were. It’d been a quarter of a century since Syd’s last disastrous stage appearance – with Stars, also featuring ex-Pretty Things and Pink Fairies drummer Twink – and since then all had been quiet. Too quiet...

His absence had been maddening. In our arrogance, we’d come to seek him out, to doorstep him as though he was some dodgy company director or politician. To get him – force him, even – to explain himself. How dare he revolutionise rock’n’roll and then give it all up and just walk away without a word! Not even having the good manners to die young!

Of course there were no illusions that we are the first hacks, fans or weird obsessives to go looking for Roger ‘Syd’ Barrett. And, as one grouchy neighbour made clear to us, we weren’t even the first to turn up that day.

After half an hour of knocking on the door, we stuffed a note through the letterbox, sat in the car and waited. By midnight there was still no sign of anyone. If he was hiding in the house, he was sitting there with all the lights out. We gave up and left; if we’re honest, we were relieved not to have found him. It was never that Syd was ‘lost’, he just really never wanted to be found.

Like Robert Johnson, Syd Barrett’s recorded legacy is slim. There are 40-odd songs, mostly written during a rich creative period from 1966 to 1967, ranging from the cosmic freak- out of Interstellar Overdrive to the childish whimsy of The Gnome to the cracked and melancholy Jugband Blues. Yet these songs drew up the blueprint that would shape Pink Floyd for three decades – they never really emerged from his shadow – as well as for the post-psychedelic progressive rock scene.

His two solo albums and the handful of demos and outtakes that have surfaced in recent years collapsed into his own little world; Edward Lear-like nonsense poetry and jittery post-acid comedown folksiness. They sold poorly at the time, though a devoted cult of believers has tended to his flame all the way through the long decades of his silence.

One could argue that Syd looms large in the history of punk rock,

the lo-fi indie scene and the new generation of psychedelic folkies like Devendra Banhardt. Everyone from The Jesus And Mary Chain to David Bowie has covered his songs and paid some homage to his inspiration. And the inspiration was not just his music. Everyone loves a ‘mad genius’, a star that explodes and leaves a vacuum in its wake. Better to burn out than to fade away.

His is a potent myth: a heartachingly beautiful man, the person that everyone wanted to be around, a powerhouse of musical and artistic talent. The drugs that helped to fuel and sustain this maverick creativity also helped to push him over the edge into the realm of mental illness. At the peak of their fame on an American tour, Syd started to behave oddly. He would go into catatonic trances. He would be unable even to mime let alone perform his songs. In the space of a year the man who had helped to revolutionise – no exaggeration – English rock’n’roll was a burnt-out case, ejected from the band he had formed and shaped.

The solo albums that followed were dark and disturbing with pitiful sales. After the second one, everyone – not least of all Syd himself – seemed to have given up on his music career. In a 1970 interview around the recording of his second album, Barrett (published in Barrett fanzine Terrapin in 1974), he was asked if he was looking forward to performing again. “Yes, that would be nice,” he replied. “I used to enjoy it, it was a gas. But so’s doing nothing. It’s art school laziness, really.”

Syd, it seemed, both burned out like a supernova and then spent the decades until his death fading away. Yes, his absence was certainly maddening. In 2009, Iggy Pop was advertising car insurance and the New York Dolls and the MC5 were regularly touring and recording despite key members having died off decades ago, so there was something about Syd’s retreat from his own legacy that really rankled. Poor mental health isn’t a barrier to a comeback: look at Roky Erickson, Brian Wilson, Arthur Lee and even Sly Stone. Nobody is too ‘unstable’ to come back, do one of those fawning broadsheet retrospectives, play Glastonbury, duet with some twat like Pete Doherty or maybe make an ad for Apple computers.

It wasn’t for lack of trying: people had tempted Syd for years. Jimmy Page and Brian Eno expressed interest in producing him in the early 70s, and later on The Damned approached him to produce their second album, Music For Pleasure (they ended up settling for Floyd drummer Nick Mason instead).

But, goes the myth, Barrett was beyond it all, a recluse, holed up in his mother’s Cambridge house, lost forever in an acid casualty wilderness. At various times it was reported that he was in a mental hospital, that he had died, even that he was recording in secret.

Most famously, he turned up in the studio when Floyd were recording Wish You Were Here in 1975 (it’s a matter of conjecture as to whether or not they were actually working on Shine On You Crazy Diamond, their soaring tribute to him). Overweight, hair and eyebrows shaved, it was the first time that any of the band had seen him in almost five years. Roger Waters was apparently reduced to tears. When asked what he thought of Wish You Were Here, Barrett said it sounded “a bit old”. He later attended David Gilmour’s wedding and slipped away from the party. That was the last time any of the band ever saw him.

Some psychedelic stories are a long, strange trip but the story of Syd is more akin to being shot out of a cannon. He arrived in London to join The Tea Set (aka The T Set, the Screaming Abdabs, The Abdabs and the Architectural Abdabs) in 1965. Syd wasn’t yet 20. A self-taught guitarist inspired by Stax mainstay Steve Cropper and rock’n’ roll icon Bo Diddley, he gave the band their new name when they found themselves on the same bill as another group called The Tea Set. The Pink Floyd Sound soon became part of the tiny London underground scene. Barrett pioneered new guitar techniques that involved feeding it through echo boxes, using a Zippo lighter as a slide. The band were booked at the UFO Club in late 1966 and soon became the first superstars of the British underground.

It’s hard to convey how quickly the music scene changed. In 1966, most British musicians had few ambitions beyond playing R&B. A year later they wanted to surrender to the void and journey to the innermost centre of eternity.

LSD had been doing the rounds in underground circles for a few years. It was not actually made illegal in the UK until 1966. Many on the scene had used it and Barrett was seen to gobble it like Smarties. While there is no doubt that psychedelic chemicals opened the user’s mind to new possibilities, Pink Floyd were bringing to rock music some of what progressive jazz musicians like John Coltrane and Thelonious Monk had been doing for some time (and were similarly chemically inspired).

The long, drawn-out songs like Interstellar Overdrive would be the template for post-Syd Pink Floyd and the psychedelic and progressive bands who followed. The fairy tale songs like Bike tapped into other traditions like music hall songs, children’s songs and folklore. The debut album, The Piper At the Gates Of Dawn, was bloated with possibilities.

Gilmour has gone on record as saying he believed Syd’s drug use merely exacerbated a problem that was already there – that the breakdown would have happened anyway. The band were touring incessantly and Syd was under pressure to write another hit single to follow up Arnold Layne and See Emily Play. As time progressed, Waters referred to “The Syd problem” as Barrett became increasingly isolated from the band and unable or unwilling to perform. One solution that was mooted was that Syd would record and write but not tour. Syd, on the other hand, suggested hiring two sax players and a girl singer. By early 1968, after a few shambollic gigs as a five-piece – Barrett’s friend Gilmour had been drafted in as a second guitarist and, it was vainly hoped, as a stabilising influence on Syd – Barrett was out. The band’s second album, A Saucerful Of Secrets, was recorded with little input from Syd. The closing track, Jugband Blues, is a bleak and evocative description of a breakdown, a sad farewell to the Floyd. His last contribution to the band was the song Vegetable Man. Then-manager Peter Jenner explained: “It’s just a description of what he’s wearing. It’s very disturbing. Roger had to take it off the album because it was too dark.”

The two solo albums that followed are a more low-key expression of that dark insanity. Recorded with Gilmour – the musicians had to play around Syd, who seemed incapable of playing the same song the same way twice – they sound like psychedelia stripped of all the effects and studio wizardry, leaving only the actual musical and lyrical weirdness beneath.

Syd then joined Stars, a sort of three-piece supergroup with Twink. At one show Syd froze onstage and then walked off. Twink recalled meeting him in the street a few days later. Syd read him a bad review of the show and quit there and then.

And that was Syd’s career in music. Afterwards, according to legend, he became a hermit. A virtual shutaway, lost forever in his own psychosis, unable to communicate.

Since his death, however, another picture of Barrett has emerged. According to his sister Rosemary, in an interview with The Times, Syd was neither mentally ill nor was he a recluse. He had spent a short time in a private “home for lost souls” and had seen a psychiatrist, though he was not on any medication nor in

a therapy programme. He was shy and retiring, though loved the company of his nieces and nephews, was chatty to the staff in the DIY and gardening stores he frequented, and had lived alone and looked after himself since the death of his mother in 1991. He had turned his back on music and wanted nothing to do with it, but he was a keen gardener, had returned to his first love – painting – and had even written a book about the history of art.

“He avoided contact with journalists and fans. He simply couldn’t understand the interest in something that had happened so long ago and he wasn’t willing to interrupt his own musings for their sake,” she said.

Syd would paint large canvasses, photograph them and then destroy them. He didn’t like to be reminded of the past; he went round to his sister’s to watch a BBC TV documentary about him and the Pink Floyd, but left, complaining that it was “too loud”.

Driving away from Cambridge that night, we like to think that a neighbour was giving Syd the secret knock and whispering, “It’s okay, they’ve buggered off back to London.” Syd would then emerge from his refuge, make a cup of tea, pick up his guitar and then sing one of the many songs that he’d written but never recorded, songs that he alone would ever hear.