The popular perception of an 80s rock record goes something like this. A gated snare drum going off like a gunshot. Synths, samples and digital drums jostling for elbow room in an airtight multitracked mix. A production job as shiny as the compact disc sliding into a yuppie’s Bang & Olufsen. And, most of all, a sense of unsustainable size, like bubblegum blown up too far.

It’s a glib stereotype, of course – but only just. “Everything was pushed to the limit in the eighties,” Europe frontman Joey Tempest remembers. “It was a decade of flamboyance and pushing all the faders, a hundred per cent. But it was charming, too. A wonderful decade.”

Rewind just a little further, to the 70s, and rock’n’roll wasn’t rocket science. Back then a studio was a bare-bones, all-analogue world with a human heartbeat, where records lived or died on the skill of the musicians on the floor. “If you had a drummer that could keep time, life was good,” recalls veteran producer Keith Olsen, famed for his work with Fleetwood Mac, Ozzy Osbourne and Whitesnake. “If you had a great guitar player, it was wonderful. If the songs were there, it was even better. Y’know, it was songs, performance and sound, in that order.”

“In the seventies, you had a tape recorder,” picks up Chris Tsangarides, who has worked as producer for heavyweights including Thin Lizzy and Judas Priest. “You had a microphone, a guitar with an amplifier, and a drum set. Maybe a few compressors, some reverberation plates, a bit of delay. Back then it centred on how good the band was. Then we hit the eighties and there was all this technology thrown at us. It went from tape to digital in about three seconds, and it was a bit of the emperor’s new clothes. In the eighties it was all about the production.”

Previously, an adventurous rock band would rely on Heath Robinson-style ingenuity, from John Bonham recording his levee-breaking beats in a stairwell, to Queen recreating a tap-dancer using thimbles on Seaside Rendezvous. “You really had to think outside of the box to get something different to the band next to you,” notes Tsangarides.

As hardware arrived from the tech giants of Japan and America, trailblazing sounds were just a keypad away. “The biggest technological development,” Olsen says, “was multitrack recording.”

“Those eighties records were so heavily overdubbed – because you could,” Tsangarides explains. “Until about 1974 it was sixteen-track. After that it was twenty-four-track. Then in the eighties it started to be two twenty-four-tracks together with a synchroniser. And they did Sgt. Pepper’s on four tracks, so that puts it into perspective. Us producers were coming out with all this: ‘Oh, I used twenty million tracks to do that song.’ ‘Well I used even more.’ ‘Have you heard Mutt Lange was using five billion tracks?’ It was like Chinese whispers. But really it was all to do with trying to get this ultimate, big, huge sound.”

One of the most notorious rumours of the era told of producer Mutt Lange tracking Def Leppard’s guitar strings individually. All true, Phil Collen told this writer, albeit only on certain sections: “That was for the ‘I gotta know tonight’ part from the song Hysteria. Mutt said: ‘Let’s make it so it’s got this unique sound.’ My friend walked in and he thought we were fucking nuts!”

“I mean, Def Leppard, they were the production monsters,” says Scott Gorham of Thin Lizzy and Black Star Riders. “But most of the time they pulled it off in a beautiful way.”

- The 6 best modern bands championing 80s-style arena rock

- Watch this man cover The Trooper on guitar and synth at the same time

- Ten Amazing 80s Action Movie Power Ballads

- How the synthesiser helped shape progressive music

Leppard, at least, were still in thrall to the electric guitar, an instrument that had been the uncontested tool of rock since the 50s. Elsewhere, Joey Tempest recalls, when the synth landed it not only dictated the sound of the era, but also directed the creative process.

“All these new toys came into play. Europe used to be a guitar-based band, but all of a sudden, in the guitar shop, there was another room full of synths. So it was like, ‘Whoa, what’s this?’ The Final Countdown had more keyboards because that’s what I was writing on. But some bands really did put on a lot of keyboards, and then the guitars sort of disappeared in the mix. I remember John Norum [Europe’s lead guitarist] was frustrated with how the guitars were pushed back.”

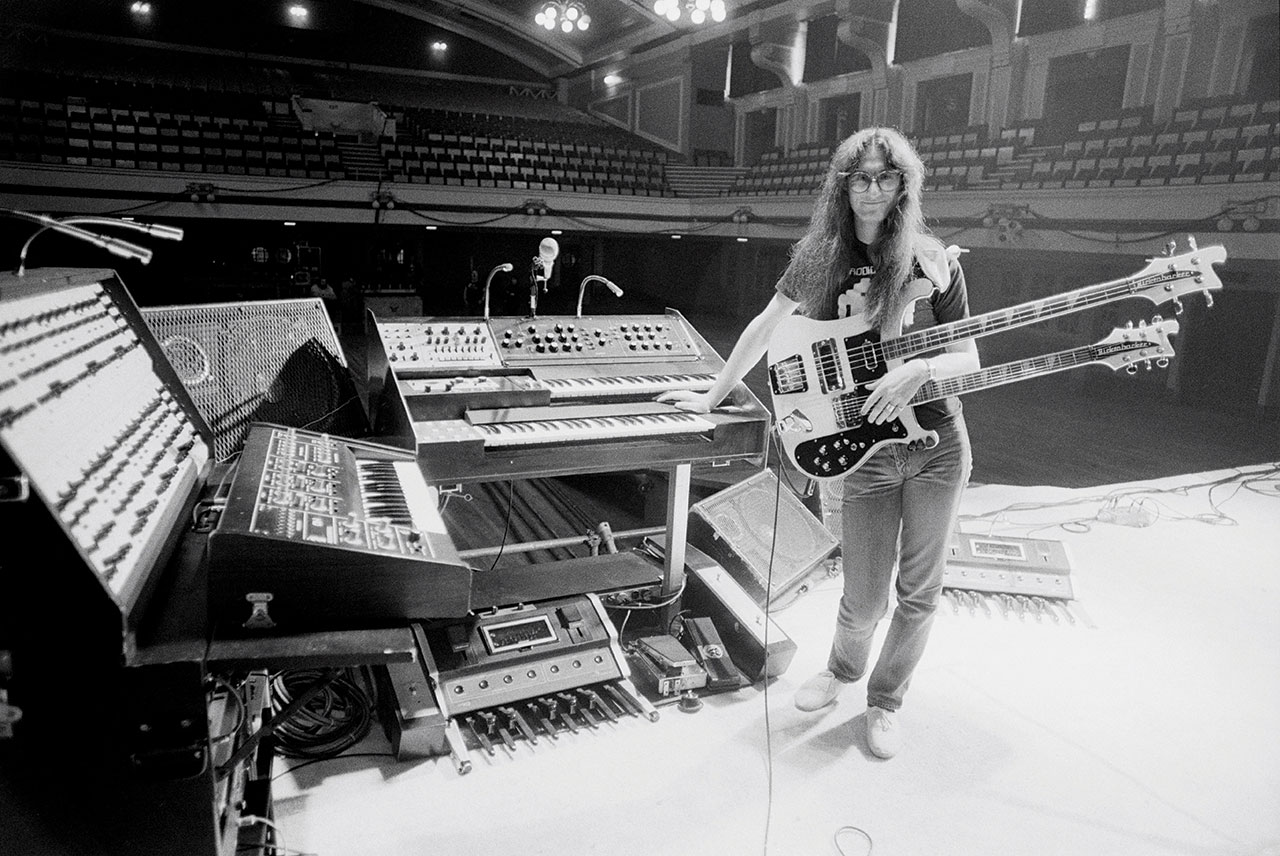

It was a familiar headache for Tsangarides, too: “You’d have these huge banks of keyboards hooked up together by MIDI – one playing strings, one playing organ, whatever you wanted – and get this absolutely massive sound. But when you put it into the track, you couldn’t hear the guitar. It just didn’t marry at all. I’d think: ‘How come I can put on a Deep Purple or Uriah Heep album from back in the day and I can hear everything? What’s going on?’ Then it dawned on me that, y’know, that was all analogue equipment.”

Ironically, the ubiquitous gated drum sound began as a quest to emulate those 70s productions. “People were after the Bonham sound,” explains Tsangarides. “But this wasn’t it. The gated drum sound is a short reverb that has a noise gate on it, so it cuts it off. It’s just like – bam! This is the sound Phil Collins used on his toms for In The Air Tonight. I used to hear it all the bloody time. You had this fricking loud snare drum, and then some poor sod trying to get his guitar heard above it.”

Even further removed from Bonham’s monster Ludwig kit were the thin hexagonal pads of Dave Simmons’ nascent electronic drums, launched in 1980. “On their own they sounded like arse,” says Tsangarides. “But on Thin Lizzy’s Thunder And Lightning I triggered a set of Simmons toms from Brian Downey’s drum kit and mixed them in with the real drums. That’s why that album sounds like it does, in a way.”

Even when it came to the latter stages of a record, the producer adds, there were expectations. “You couldn’t mix a record unless you had five hundred bits of outboard gear. There was this thing called the Aphex Aural Exciter. You couldn’t buy it. You couldn’t rent it. What would happen was, you used this machine on your final mix and they’d charge you something like seventy-five pounds for every minute of song. And all it did was make everything sound really toppy. Pointless. But it was like, ‘You’ve got to have one of these… because they’ve got one!’”

As well as one-upmanship, producers were also motivated by the prevailing media. “Radio in America was so important for all these producers,” Tempest points out. “And the ones that had a brain understood the expansion and the limited EQ that radio actually added, and they didn’t push things too much.”

“The CD format was a factor, too,” says Tsangarides. “Because here’s the thing: when you mixed for a record, there were certain criteria. You couldn’t make the vocals too bright. Too much bass, the needle jumps out of the groove. When CDs came along, good, bad or indifferent, however much bass or treble you had – even if it sounded total arse – it would still reproduce. So that stuff did have an effect on things.”

As did the financial health of the 80s record industry. “I was lucky enough to be looked after by Zomba Management,” says Tsangarides, “who also had Martin Birch, Mutt Lange, Tony Platt. Battery Studios was our home from home in London. And it was like: ‘What do you need?’ Any piece of equipment, any mic, you could have it. They put this ethos in you that it has to be the best. They’d never look down their noses, like: ‘It’s taken you six months to make the record.’ Good grief, no. It was all: ‘Oh, we’ll go to Barbados to record the bass drum.’ It got silly. I think we did disappear up our own jacksies. Not on everything, of course.”

It’s important to differentiate, says Tempest, between the 80s producers who struck a balance and those who created monsters. “You had the guys who understood how to do it, like Mutt Lange, Martin Birch, Bob Rock, Bruce Fairbairn, Ted Templeman – usually the ones who started in the seventies. But they were the good guys. Then there was the younger breed coming in who would push it even more. Towards the end of the eighties it was the kitchen sink, basically. People thought it sounded bigger, but it didn’t. When everything was done, you’d compare it to a straightforward rock album and you realised, ‘Hang on, it got smaller.’”

“People would put on eighteen tracks of guitar doing the same thing,” Tsangarides says with a sigh, “because ‘It’ll sound mega, man’. Well, it didn’t. Because you’ve still only got the same frequency spectrum. So the more you put on, the smaller it sounds.”

The sonic inflation couldn’t go on forever, of course. Just as the hair-metal bands of the 80s were rendered archaic by the route-one songcraft of grunge, so the era’s production values were cruelly exposed by a wave of lean incoming albums. “The nineties was a real breath of fresh air, to be honest,” says Tsangarides. “Whether you liked the music or not, things went more back to basics. Y’know, band in a studio, with a producer, ‘one-two-three-four’, off they go.”

“It went back to the roots,” says Tempest. “Soundgarden did some great productions. Butch Vig did a great job on Nirvana’s Smells Like Teen Spirit.”

Three decades later, quantifying the merits of the 80s sound is a slippery task. The lazy, broad-brush consensus is that this was an era whose plump, pompous sonics should serve as a cautionary tale. Closer to the truth, Tempest offers, is that 80s albums must be judged on a case-by-case basis.

“Some of those productions are hard to listen to today. But that’s not to say it was all worse. If you listen to Whitesnake’s 1987, it’s pushed to the limit. But it’s still one of my favourites. Appetite For Destruction was pushed a bit, but it was an actual sound. Martin Birch’s productions for Iron Maiden were great. Aerosmith and Bruce Fairbairn with Pump, that still sounded like a real band. Europe? I think we were on the right side. We didn’t push things too much. But a lot of productions did.”

“But there were some amazing-sounding records anyway,” says Tsangarides. “It was a great time. It was kind of the peak of the great British recording studio. These days, musicians hear the old stuff and ask: ‘How come my album doesn’t sound like that?’”

“Bottom line,” concludes Olsen, “if it’s a great song, I don’t care when or how it was recorded. Because technology can’t get in the way of a great song.”

The Top 10 Best 80s David Bowie Songs

Foo Fighters' Taylor Hawkins in solo 80s throwback video

Dysfunctional Days & Crazy Nights: The Epic Story Of Kiss In The 80s