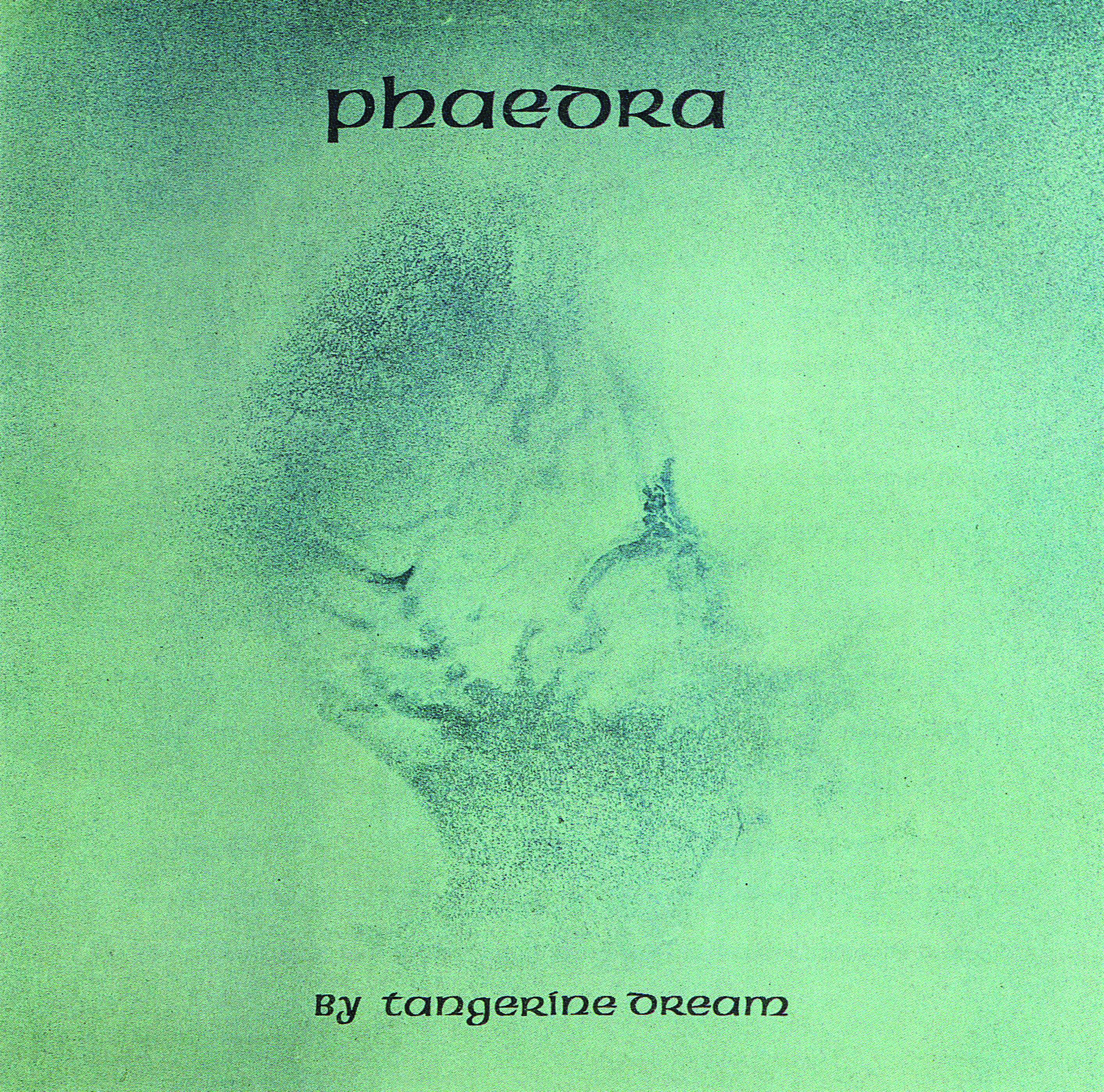

Fifty years ago, electronic music got a new beat when Tangerine Dream released Phaedra. The pioneering German group’s fifth studio album saw the Berliners relocate to the English countryside, and its motorik grooves played a key role in what was being defined as krautrock. In early 2024, to celebrate the album's 50th anniversary, Prog told the story behind one of the greatest experimental electronic albums of all time, its legacy and the synthesiser that informed its sound.

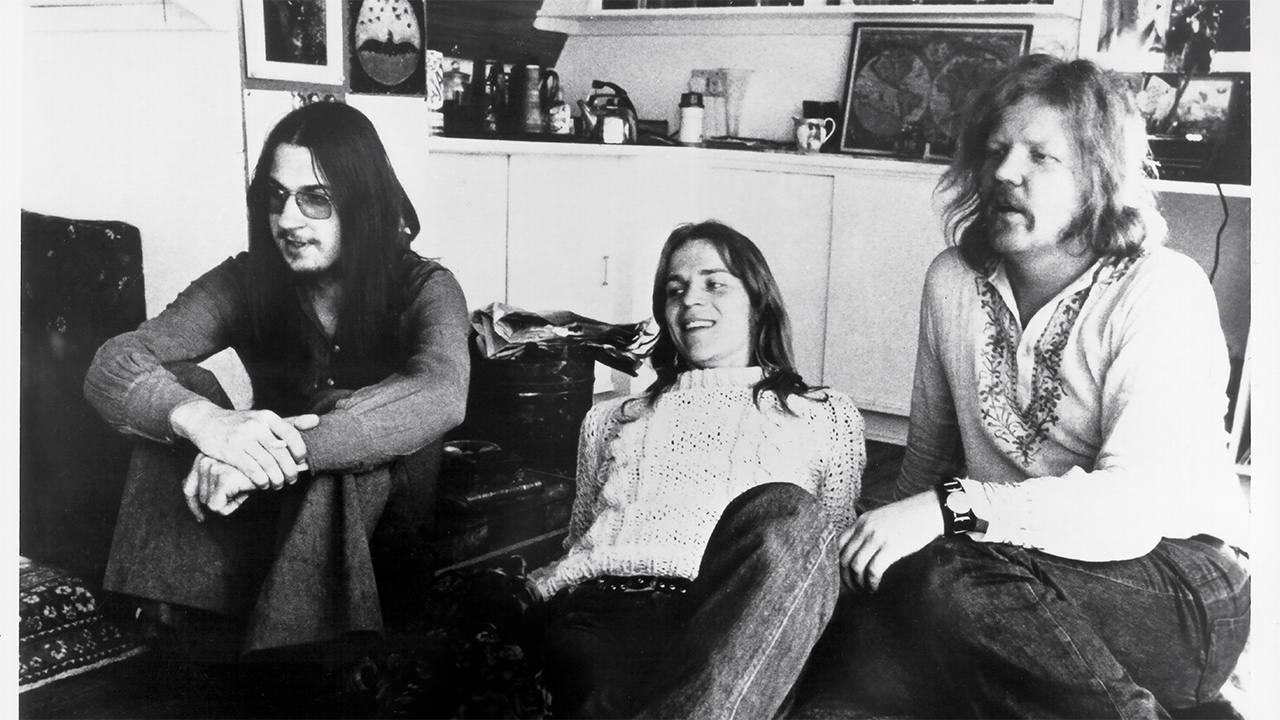

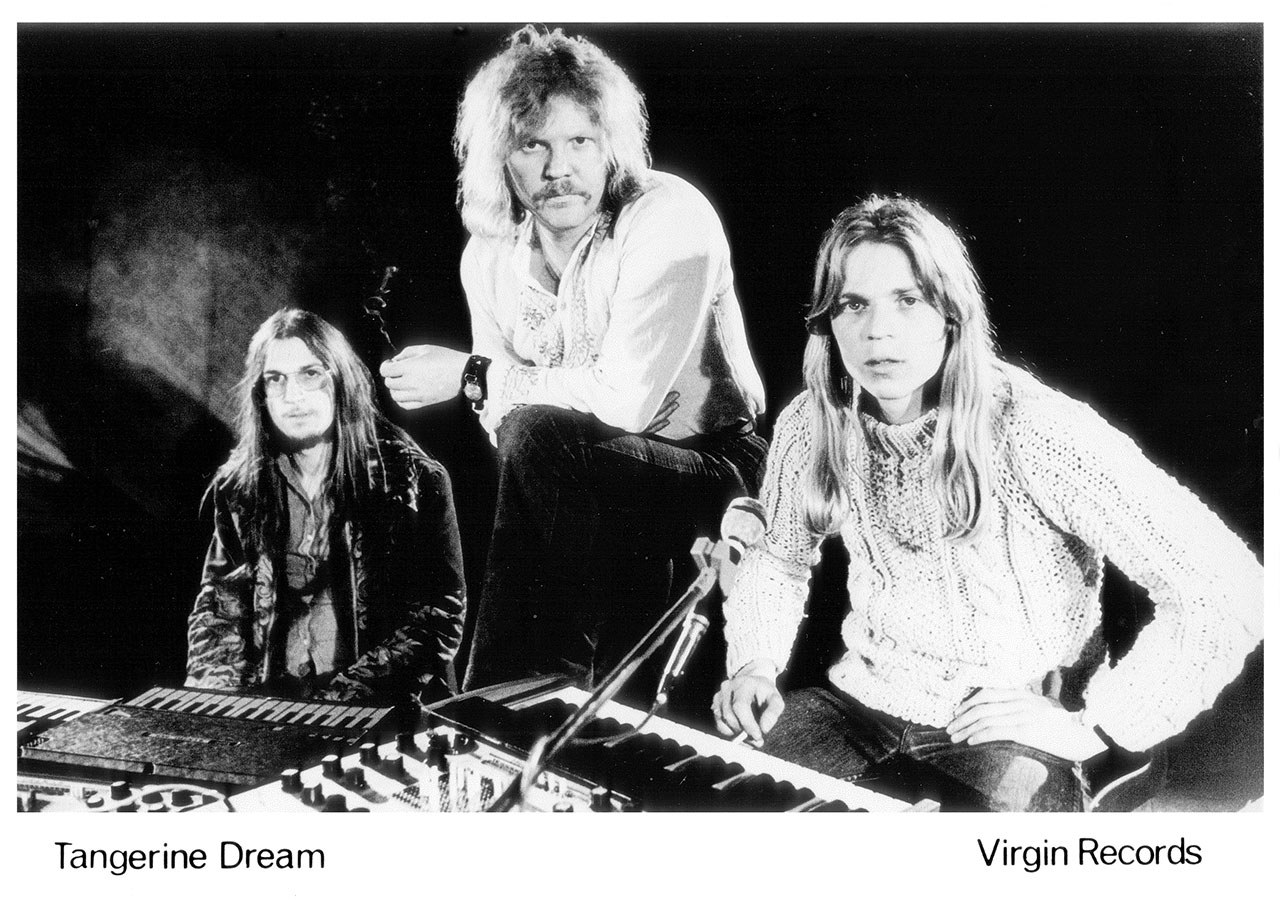

November 1973. Frayed bell-bottoms were the height of fashion; Pink Floyd culminated their Dark Side Of The Moon tour and the Mariner 10 spacecraft blasted off on a mission to send back the first-ever photos of Mercury to an eagerly awaiting Earth. Meanwhile, in the little Oxfordshire village of Shipton-on-Cherwell, three visionary musicians armed with cutting-edge technology were about to alter the musical landscape forever. Edgar Froese, Peter Baumann and Christopher Franke – otherwise known as Tangerine Dream – flew from Berlin in Germany to Richard Branson’s The Manor to record an album that would change their lives and that of the many people who would hear it. It was a record that was to achieve great things, blowing minds with its sheer invention and inspiring decades of electronic music.

For Branson, it was a propitious time. Virgin Records was in the second year of its existence and riding high on the phenomenal success of Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells. The label’s mail order service was in full swing, providing fans in England with advance access to the cream of American imports. Never one to rest on his laurels, the entrepreneur had travelled in person to Germany to recruit his latest act.

By the time they signed to Virgin, Tangerine Dream had already released four albums via German experimental label Ohr. They’d also undergone multiple changes in personnel, with founding member Edgar Froese the only constant. For their previous two long-players, however, Zeit (1972) and Atem (1973), they’d settled on what is now considered their classic line-up.

Froese was the group’s creative powerhouse and polymath; an instinctive musician who’d also studied painting and sculpture at the Berlin Academy of Arts. On tour in Spain with his first band, The Ones, Froese had performed a special concert for the surrealist painter Salvador Dalí. It was a meeting that infused him with a passion for experimentation. Returning to Germany, he formed Tangerine Dream in 1967 with a long-since forgotten line-up of Lanse Hapshash (drums), Kurt Herkenberg (bass), Volker Hombach (sax, violin, flute) and Charlie Prince on vocals. By the time Christopher Franke joined in 1971, after a stint as drummer for The Agitation – later renamed Agitation Free – Steve Jolliffe, Klaus Schulze and Conrad Schnitzler had all passed through the band’s ranks.

Peter Baumann also came on board that year, at the crucial point when the band were shifting from guitars to electronics. For Baumann, a career in music was never planned.

“Oh, no, not at all,” he admits. “Everything that happens in my life is an accident. And it was a very simple story: I had a buddy in school, and we were just chatting. He said, ‘I’m playing in a band, why don’t you come along and listen?’ So I went. They had a bass player, guitar player, vocalist and drummer, but no keyboard. So I said, ‘Why don’t I go on keyboards and join you?’ And that was it.”

Primarily a covers band, this was a good experience for Baumann, but not fulfilling. It was another accident of fate, a chance meeting, that

initially led to his involvement with Tangerine Dream.

“I was at a concert – Emerson, Lake & Palmer,” he recalls. “They started late, so I began to talk to the folks behind me. There was a guy with long, dark hair named Christopher. We were chatting about what we were doing. He said he played in a band. I said, ‘I do some experiments with music as well.’”

Bonding over a shared love of instrumental records, the two exchanged details and, a week later, Baumann received a note from Franke urging him to get in touch as they were looking for a new keyboard player.

“So I called up,” recalls Baumann, “and about a week later, they invited me to bring my keyboard and meet them at a rehearsal room. The rest is history.”

Over their following two albums, Zeit and Atem, Tangerine Dream set about exploring new sounds.

“The music was evolving, intuitively,” says Baumann. “You’re always trying new things and you say, ‘Hey, that seems to work’, but we never really discussed the music much. It was more like: have a good joint and then start playing.”

With Phaedra, however, that changed.

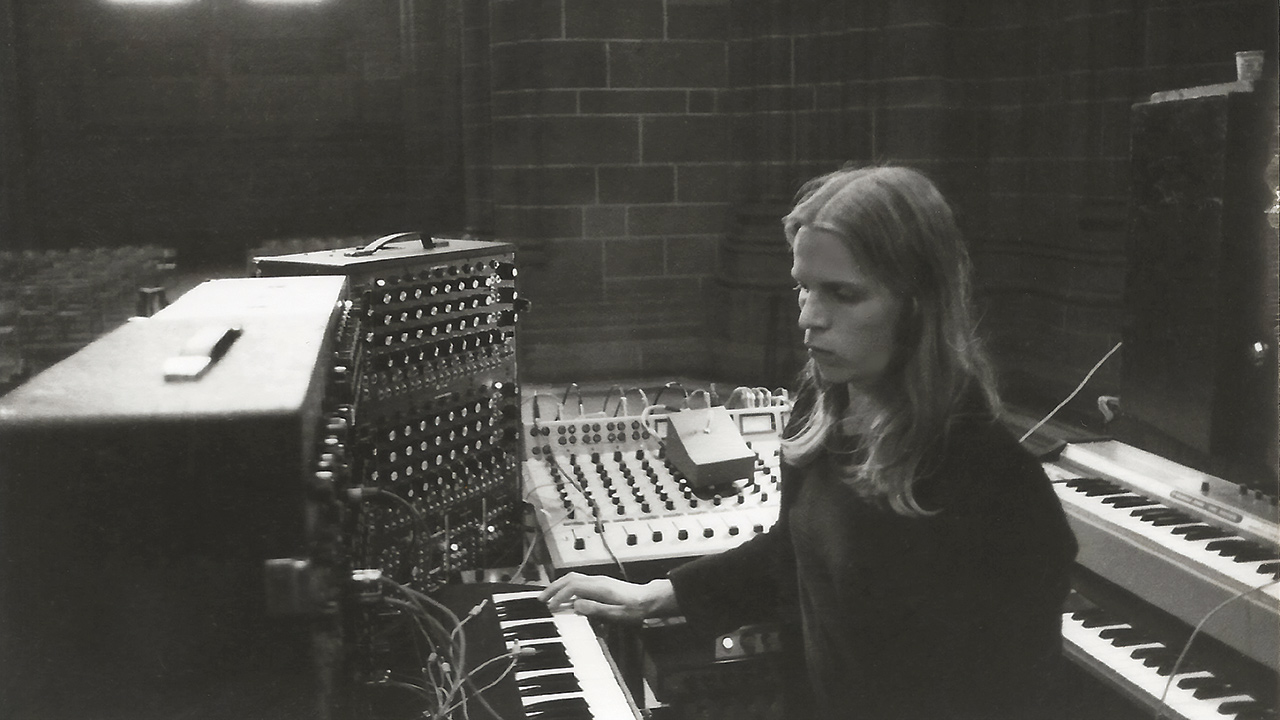

“The major difference was that it was the first record where we had

a Moog synthesiser,” remembers Baumann. “That was very unique at the time, and it really set the flavour for the main piece.”

The synthesiser in question came to the group via an unusual path. Sometime in 1969, The Rolling Stones had purchased a complete modular system from Moog, one of the very first commercially available. The Stones’ experiments with the nascent technology ultimately led nowhere. Dissatisfied, they sold their equipment to the Hansa Studio in Berlin, an establishment that would later become famous through its use by David Bowie, Iggy Pop and others. Back in 1973, Hansa accepted an offer for the Stones’ old Moog from Tangerine Dream’s Christopher Franke. A bargain at only $15,000 – an equivalent of about £90,000 in today’s money.

Franke paid for the Moog using the band’s advance from Virgin. Baumann recalls how the group’s contract with Branson’s company came about.

“He [Branson] was looking for bands. And I think it was Simon Draper [Virgin Records co-founder] who told him there were a few bands in Germany – Faust, Can and Tangerine Dream – that he should check out. So he came to Berlin. We got along famously, and he made us an offer.”

Fast-forward to November, 1973 when the group decamped to Oxfordshire and set up home in The Manor.

“We recorded pretty well in Germany,” says Baumann, “but The Manor studio was a whole different ball game. We had a really nice

16-track machine and really good outboard gear. It was a beautiful facility. For three weeks we got in there and recorded Phaedra.”

It was a record that grew organically.

“We never had any clear idea of what we were going to do,” stresses Baumann. “There was one commonality – that is we would start very, very simply and see what happened. Even in live concerts we started from one note and then developed from that one note. That was the only thing that we ever discussed.”

Tangerine Dream’s influences at the time came largely from fellow

sonic experimenters.

“We listened to a lot of instrumental music,” recalls Baumann. “Stockhausen and Ligeti – a lot of classical composers who did very experimental things.”

Born in 1928, German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen was an early innovator in electronic music. Nearly 20 years before Phaedra was realised, his pioneering Gesang Der Jünglinge had mixed human voices with electronically generated pulses, tones and white noise. Around the same time, Transylvania-born György Ligeti had begun utilising micropolyphony – dense lines of sound moving at varying tempos and rhythms.

“From the popular bands,” says Baumann, “we listened to Pink Floyd’s Ummagumma and then The Dark Side Of The Moon. The instrumental sections – they were our favourites.”

The genius of Froese, Baumann and Franke, based largely on instinct, lay in combining these disparate elements into a wholly original model. Even during recording, they had no idea how Phaedra would sound in its final form.

“We recorded quite a bit,” explains Baumann, “and a lot of it was junk that we threw out. But obviously [the title track] worked very well, and so we refined it a little bit in the studio. It’s not a live situation, so in the studio we could do some overdubs.”

It was a process of going back and forth between the three.

“We never discussed the music; we’d just say, ‘I like it’, or ‘I don’t like that.’ So, you know, it was a collaboration on many different levels, and it was extremely intuitive. There was, especially with Phaedra, never any fighting or disagreements or anything like that. It was really a very instinctual and homogeneous collaboration.”

According to Baumann, the novel environment they found themselves recording in helped to shape the music.

“In hindsight, it was a much better atmosphere. We enjoyed being in the country; The Manor was a great facility and we loved being there. And we’d never before worked three weeks in a row. Although I was, at the time, 19 or 20 years old. I wasn’t paying much attention to the bigger picture.”

Even when things were going well, the band had no sense that the Phaedra project would amount to their largest success to date.

“We just knew that we liked it,” says Baumann. “I mean, there was really no comparison. It was so unique. Nobody else was doing anything like that. We just enjoyed it. And we thought it was cool. Very cool.”

The lengthy sessions were not without their challenges. Speaking in an interview for Mark Prendergast’s comprehensive study of electronic music, The Ambient Century (2000), Edgar Froese confirmed:

“Technically, everything that could go wrong did go wrong. The tape machine broke down, there were repeated mixing console failures, and the speakers were damaged because of the unusually low frequencies of the bass notes.”

Frequent power cuts added to the band’s woes. A miners’ strike was in full swing and commercial users of electricity were prohibited at certain times. To further complicate matters, incessant rain found its way in through the roof of the old building, leading to a mass scramble to protect precious instruments and equipment by binding it in plastic sheeting. A particular low point occurred when Froese witnessed the Manor’s resident Irish wolfhound amble in, raise its leg, and urinate against the band’s Mellotron.

Despite these travails, staff at The Manor did their best to maintain a good atmosphere, and gradually Phaedra took shape. The band worked long days, beginning mid-morning and toiling on into the small hours. With no presets or writeable memory, setting up the Moog alone proved to be time-intensive. The results, though, were worth it. The synthesiser’s driving arpeggiated bass line provided a stunning bedrock for the group to build on, using Mellotron, guitars and electric piano to construct a hypnotic, layered soundscape. A quirk of the new equipment was its extreme sensitivity to heat: when the Moog warmed up, it also went out of tune. The trio used this to their advantage, letting the Moog have its way and incorporating the results into the title track.

The finished album was released in the UK on the February, 20 1974 and, to the average listener, Phaedra must have sounded like a broadcast from an alien planet. The title track alone proved a revelation. Occupying the entirety of side one, Phaedra itself builds from an uneasy synth bubbling, gradually coalescing into a hypnotic, polyrhythmic entity, shifting like a kaleidoscope through multicoloured clouds of Mellotron tones. The three tracks comprising side two, Mysterious Semblence At The Strand Of Nightmares, Movements Of A Visionary and Sequent ‘C’ form something of space rock symphony, taking the listener on a beguiling journey to strange, distant galaxies. Phaedra provided music that seeped into the soul. Nothing quite like it had invaded the UK’s airwaves and bedrooms before.

Not surprisingly, some responses from critics were openly hostile, including an infamous diatribe from Melody Maker’s Steve Lake, who described the record as “gutless and spineless, devoid of inspiration” Despite such vitriol and spurred on by exposure from far-sighted radio DJs such as John Peel, Phaedra gradually grew into something of a phenomenon. In a wonderful bit of poetic justice, it broke Melody Maker’s own Top 10. Baumann was as surprised as anyone by the record’s success.

“It was very funny – a week or two after it came out, I was in Italy with

a girlfriend and I got a telegram from Richard [Branson] saying, ‘You have to come to London, your record is in the Top 10.’ I thought, what is he talking about? I had no idea, so I called him, and he said, ‘No, no, Peter, it’s in the Melody Maker Top 10.’ And so I went to London to do a ton of interviews.”

It was an astonishing feat for such a radical record.

“We were a totally experimental band,” says Baumann. “We weren’t rock, we weren’t pop, and we played for relatively small audiences in Germany. We didn’t even sell a lot of records in Germany. Atem and Zeit sold maybe a couple of thousands, maybe 10,000 – we never sold much in the beginning. So, I had no expectations. I was totally surprised and, you know, it was a life-changing event.”

Phaedra hit No.15 on the UK album chart, proving the critics wrong and opening the floodgates to a surge of interest in the new music coming from across the English Channel. Kraftwerk’s Autobahn, released in the UK a few months later, reached No.4 on the UK album charts and listeners soon sought out ambitious sounds from other radical German groups such as Faust, Can and Amon Düül II.

Phaedra’s success propelled Tangerine Dream to a new level of celebrity.

“I think we took it pretty much in our stride,” reflects Baumann. “The first time it hit me was when we did a couple of concerts after the album got successful: the first was in London [at Victoria Palace Theatre on June 16, 1974]. There were thousands of people there and that was kind of stunning. It just hit me: oh my God, there are actually people liking it!”

It was the first time that the band encountered their UK fans face to face. They knew that Phaedra was selling well, but experiencing the adoration close up was a shock.

“In a live setting,” says Baumann, “it’s really a completely different ball game. And it really hits you that thousands of people are spending their time and money to come to hear you. That was unique.”

For him, the album was a personal turning point, one where he began to understand that a long-time career in music was possible.

“I didn’t plan anything,” he muses. “I just did what I enjoyed doing and they [Froese and Franke] seemed like a couple of cool people to travel with, hang out with, and make music with. And, you know, there was no way that I could have planned making a living off of it.”

After Phaedra, though, music became a full-time job.

“You settle in,” says Baumann, “and then you do the next record, and you do a tour here and a tour there. Then we went to America and did tons of interviews. It became a lifestyle.”

The three young musicians adapted well, their natural level-headedness a solid anchor against the strains and excesses of the business.

“It wasn’t that difficult,” Baumann recalls. “You know, Tangerine Dream was not about personalities. None of us was a star or a special person. It was always the music that was front and centre. We had some groupies and stuff, but it was never as wild and crazy as with some of the rock bands.”

Phaedra sits proud among the many fine entries in Tangerine Dream’s extensive discography, and its influence has never dimmed.

“I think one of the reasons,” says Baumann, “is that it was one of the first electronic records and it became kind of a landmark for a lot of other folks. The difference with Phaedra is that it’s more like an interior experience rather than an exterior experience, where people jump up and down, screaming, at a rock concert. It has a very different atmosphere that lends itself very well for people to listen at home with headphones.”

It’s an album tied to the uniqueness of the time of its genesis. The newness of the technology and the set-up of the music business created perfect conditions for such an album to seep into the public consciousness.

“Yeah, it’s a very different ball game now,” Baumann reflects, “and also the distribution is very different. Everything is much more fast-paced. If you would release a record like Phaedra today, it would not be noticed, or very little.”

The ubiquitous access to music, he argues, has to some extent lessened its special aura.

“Back then there were no computers and music was a much more important part of people’s lives than today.”

In the 1970s, especially in Germany, experimentation within popular music was rife. Bands were moving away from the ubiquitous three-minute verse-chorus song with a traditional drums, guitar and bass set-up towards a more inward-looking sound.

“I think it’s the German mentality, you know,” Baumann reflects. “Over the years there have been very, very few real rock bands, you know. They had their pop music, but testosterone-driven rock music, that just was not a German thing. You had the Scorpions at the time, and maybe one or two other bands, but I think Germans, they live more in their heads than in their guts.”

Phaedra is a landmark of such cerebral, transformative music and, half a century on, it continues to resonate. And Baumann continues to be surprised by its enduring popularity.

“Here we are 50 years later doing an interview. And yeah, I didn’t think that it would last that long,” he admits.

As with any long-lived band, Tangerine Dream have drifted in and out of prime focus but have never ceased to be relevant.

“There are phases when it’s more noticeable,” he agrees, “and then less – it goes through waves.”

For Baumann, it’s been a long journey with plenty of high points. “Playing the Royal Albert Hall [in April 1975] was obviously something you don’t forget,” he says. “Also Reims Cathedral [France, 1974] and New York City [on several occasions].”

Of playing live, he admits, “It’s like sex. Sometimes it’s the best thing in the world. And sometimes it’s just something that you have to do. But it’s always better doing it than not!”

And was Phaedra the album that started it all?

“I don’t listen to it very often,” he confesses, “but when I do, you know, it’s really timeless. It was always in its own world; it didn’t fit into any category.”

Legions of fans would surely rush to agree.