In his 2007 memoir, Eric Clapton vividly recalls hearing Steve Winwood for the first time. The guitarist was in the early flush of his career playing in The Yardbirds when he encountered the Spencer Davis Group in clubland in 1963. Winwood, SDG’s precocious singer/organist, may have been just 15 but, Clapton notes: “If you closed your eyes you would swear it was Ray Charles. Musically he was like an old man in a boy’s skin.”

Bob Dylan was gripped by a Spencer Davis Group gig three years later, midway through his UK tour. Afterwards, as seen on the Eat The Document film, an open-mouthed Dylan asks of Davis: “How’d he learn to sing like that?” To which Davis, appearing lost for an answer, merely replies: “Well, since the day we found him.”

Steve Winwood always seemed fully formed from the start. He was still in his teens when he quit the Spencer Davis Group and formed Traffic in 1967, leaving behind a trail of huge-selling hits, among them Keep On Running, Gimme Some Lovin’ and the somewhat ironically titled I’m A Man.

At 21 he was in Blind Faith, the band that came to embody the late-60s ideal of the mercurial supergroup. Winwood was so much in demand as a musical ally – helping out Jimi Hendrix, Lou Reed, George Harrison, Leon Russell, Muddy Waters, Joe Cocker and Howlin’ Wolf, to name but a few – that he was an industry veteran by the time he finally got around to a solo career in the latter half of the 70s.

“I came into music from a slightly different direction than some of my contemporaries,” he tells Classic Rock today. “I started off playing with my dad, learning thirties and forties dance music and American classics, which wasn’t particularly easy stuff. And I was a chorister in the High Anglican church. That music got under my skin somehow. Then along came skiffle and early rock’n’roll and Buddy Holly. And later on came Ray Charles, who introduced me to this crossover from bebop and jazz into rock and R&B. I was so engrossed with learning all these different kinds of music, and trying to play them all, that being on stage was just part of it. It didn’t occur to me that there was anything I should shy away from.”

If there’s one prime directive in all of Winwood’s work, it’s an inclusive approach to music making; there’s very little that’s off limits to his imagination. “With Traffic we made a conscious decision that we would try to incorporate a lot more elements – folk, jazz, ethnic music and even bits of classical music and different forms,” he explains. “I’d probably say that I’ve been trying to do that ever since.”

Growing up in the Great Barr area of Birmingham, Winwood might easily have followed his father into the family’s local foundry business. But music took hold at an early age. He was eight when he made his stage debut, playing in the same band as his father, a semi-pro musician, and elder brother Muff. Stevie became a regular on the Midlands R&B scene in his early teens, before he and his sibling formed the Muff-Woody Jazz Band.

Looking to put his own group together, Spencer Davis caught them one night. “They were playing a form of music that was a step up from traditional or New Orleans jazz,” he recalls today. “I walked in and there was this kid, pretty much not long out of short trousers, who played piano like Oscar Peterson and sang like Ray Charles. I asked him if he’d like to be in the band and, in a lovely little Birmingham accent, he went: ‘I’d love to, but I don’t have a driving licence.’ I told him I’d come and get him, because I had a beaten-up old Bradford, which I’d paid fifty quid for.”

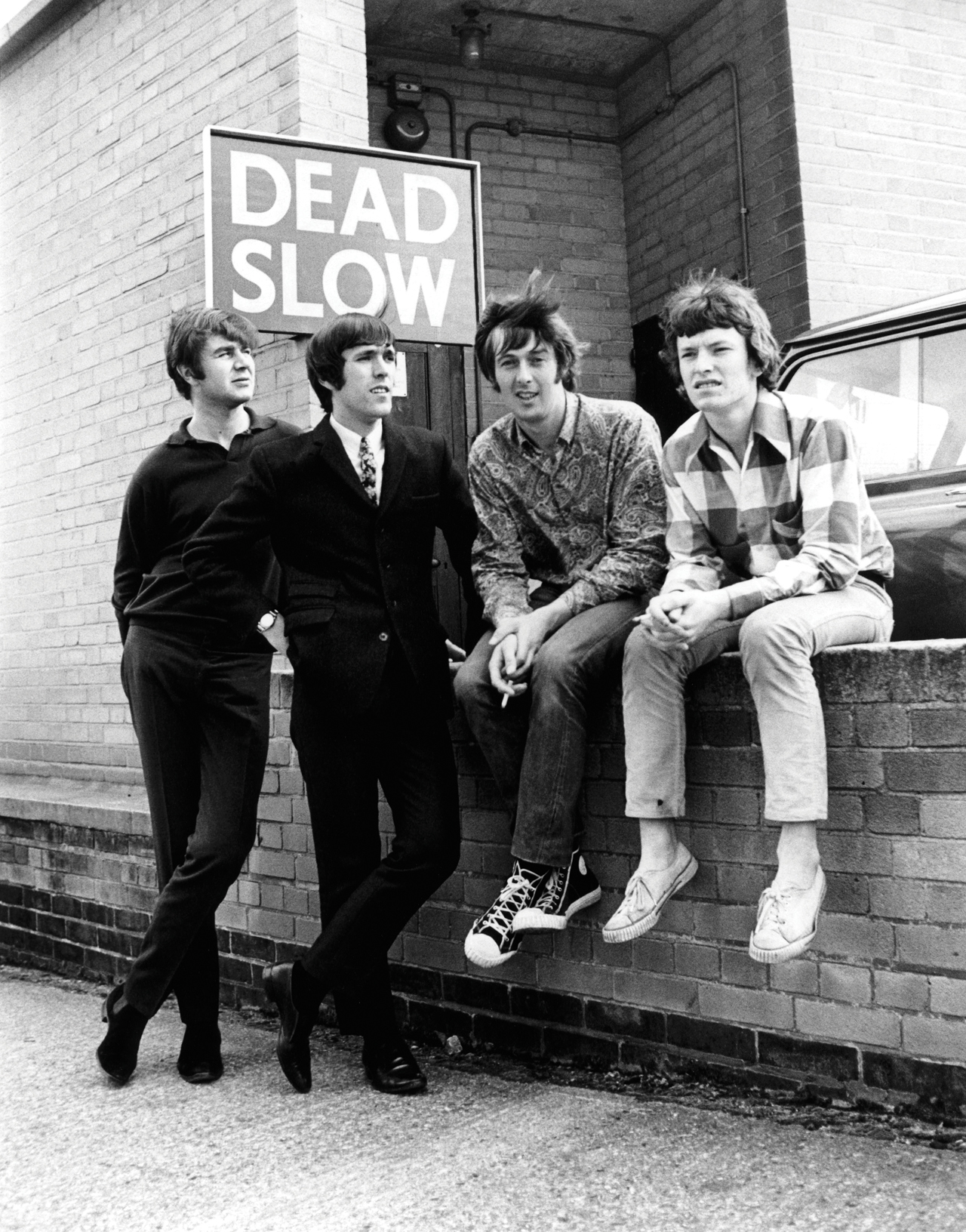

With Muff also on board as bassist, alongside drummer Pete York, the quartet started working up tunes by Jimmy Reed, John Lee Hooker, Lead Belly and Woody Guthrie. Before long they’d secured a weekly residency at the Golden Eagle, and soon attracted a BBC crew to film the queues around the block.

“With Spencer Davis we were discovering blues and R&B, all this fantastic music we were hearing from America,” says Steve. “They were singing in a form of English and a lot of the time I didn’t understand what they were talking about, like ‘another mule kicking in your stall’ [from Muddy Waters’s Long Distance Call, referring to someone else making moves on your loved one]. There were lots of things like that. And by not being able to emulate that stuff accurately or faithfully, we were inadvertently creating our own style.”

Life as a touring musician soon took precedence over everything else. “I’m afraid it has to be said that I never had a proper job,” Winwood says. “At fifteen I’d be going up to play all-nighters at the Twisted Wheel in Manchester, finishing at five or six in the morning. Then on the Sunday the same promoter had a club in Hanley, called The Place, and we’d play that. I’d get home at one in the morning, then have to go to school that day. That was pretty unsustainable and I was kicked out of school.”

Had the planets aligned a little differently, Winwood’s musical life may have taken a whole other turn in 1966. Not long after the Spencer Davis Group had scored their second UK chart-topping 45 with Somebody Help Me, Ginger Baker was putting Cream together. Eric Clapton had originally envisioned the band as a quartet, with Winwood out front, although both Jack Bruce and Baker favoured a trio set-up. Clapton was outvoted, of course, but it’s tempting to imagine how Cream might have developed with Winwood also in the band.

“There was a slight lack of synchronisation in the timing of things,” says Winwood, musing on what might have been. “There came a point in the Spencer Davis Group where I thought: ‘I’ve definitely had enough of this, I want to do something else.’ But I’m not quite sure whether that occurred before Cream or not, or if I was in that mind-set. After that point occurred, though, then yes, I would certainly have taken the job.”

As it transpired, Winwood elected to form Traffic with three long‑time friends from the Midlands R&B scene – Jim Capaldi, Dave Mason and Chris Wood. The four-piece shifted around various bases in London before finally taking up residence in a remote cottage in Aston Tirrold, deep in rural Berkshire. In doing so they set the trend for bands suddenly upping sticks and ‘getting it together in the country’.

“The big problem was that we felt we couldn’t play music whenever we wanted,” Winwood says. “In London we couldn’t set the gear up in one of our flats and make a racket at two or three in the morning. So moving to the country was really a practical move. We were living at the cottage in squalor. It was kind of like a crash pad, four lads living like students. But instead of being in a university town it was half a mile up a muddy track with no electricity and water from a well. We were crusties, really.”

There were rumours, too, that the cottage was haunted. “A few people have told me they thought it was,” he says. “Of course, Jim and Chris are no longer around to talk about it [Capaldi died in 2005, Wood in 1983], but I think they both had quite vivid experiences. Whether or not that was to do with whatever substances were around or not I don’t know. Because there was a lot of that about.”

Spooked or otherwise, the cottage proved an ideal base for Traffic to conceive their debut LP. Released in December ’67, Mr. Fantasy was a minor psychedelic classic, its loose‑limbed songs stirred by exotic rhythms, soulful white blues and Eastern strangeness. Its standout tune was Dear Mr. Fantasy, the product of a fertile songwriting partnership with Capaldi and Wood. Its gestation, as with most things Traffic, was a little unconventional by pop standards.

“Our songwriting originally came out of a need to have material for us to jam,” Winwood remembers. “We learned to play together – I’d be on guitar or organ, Jim on drums and Chris would play flute and sax – and that gave us a freedom to move different ways. We’d do these long improvisations, and Jim, very often, would scribble down a verse or chorus on an envelope or the back of a fag packet, which I’d stand up on the organ.

“Having recorded it, we’d go back and listen to what we’d done and work out which bits to keep. That was really the way we wrote. It was only later, when Jim and I started writing with different people, that we realised that wasn’t the way most people wrote songs.”

After a second album in late ’68, Traffic were finished, at least for the short term. It was a year in which the increasingly restless Winwood guested on Jimi Hendrix’s Electric Ladyland, slipping a Hammond groove under Voodoo Chile.

By the next spring, Cream having disbanded, Winwood and Clapton started hanging out together more regularly. The pair would smoke joints and jam amid the bucolic peacefulness of Aston Tirrold. Ginger Baker popped over too, and with the addition of Family bassist Ric Grech, Blind Faith were born. Making their live debut at a huge free concert in London’s Hyde Park, Blind Faith lasted for one album and a brief US arena tour.

“Blind Faith was pretty murky, really,” Winwood remembers. “That didn’t really work out quite as well as Eric and I had intended. I don’t think there was any one reason for that, but Eric didn’t want to carry on doing what he’d been doing with Cream. We were both looking for something else. The music that we started off doing was acoustic and jangly. It had a sort of folk element to it, not something that goes down too well in the arena rock environment. But of course rock was becoming big money at that time.

“There was a lot of pressure on Blind Faith with this sort of ‘supergroup’ tag,” he continues. “We had pressures from the business to start recording before we were perhaps ready, and we were suddenly playing big places. So we were caught out a bit, adapting what we were doing to those venues, which wasn’t quite the right thing. Neither of us were into that. We were starting to lose interest at different points and were drifting apart.”

Winwood returned to the studio in 1970, initially to make a solo album, under the guidance of producer Guy Stevens. But things didn’t quite work out. Stevens wanted to introduce a few covers, whereas Winwood was more keen on something more challenging. Stevens left, and Winwood brought in Capaldi and Wood, reuniting Traffic.

The result was John Barleycorn Must Die, a prog-folk masterpiece that also voyaged into free jazz and R&B. “For me, Traffic was like coming home,” he says. “It was easier to explore music with Traffic than it had been with Blind Faith. We were utilising different kinds of music, trying to continue the legacy we’d started and which hadn’t properly come to fruition for us. There were still plenty of other things for us to explore.”

Traffic’s journey ended in 1974, amid Winwood’s recurrent issues with peritonitis (inflammation the abdomen) and after a couple of uneven final albums. The decade proved a transitional, sometimes difficult one for him. He threw himself into session work.

“Something happened in the mid-to-late seventies,” he reflects. “I dropped out a little from the rock’n’roll world. I’d been doing it for ten years since I left school and was looking for other things. So I made a conscious effort to do a lot of sessions and work as a sideman, to try to learn how other people were putting music together. I toured as a sideman with John Martyn and played with a lot of amazing people during that time. Then later on, of course, punk emerged. I found that tricky, because punk rock was almost a reaction against what I’d been doing. It was difficult for me to grasp that, so I suppose I sort of went underground a little.”

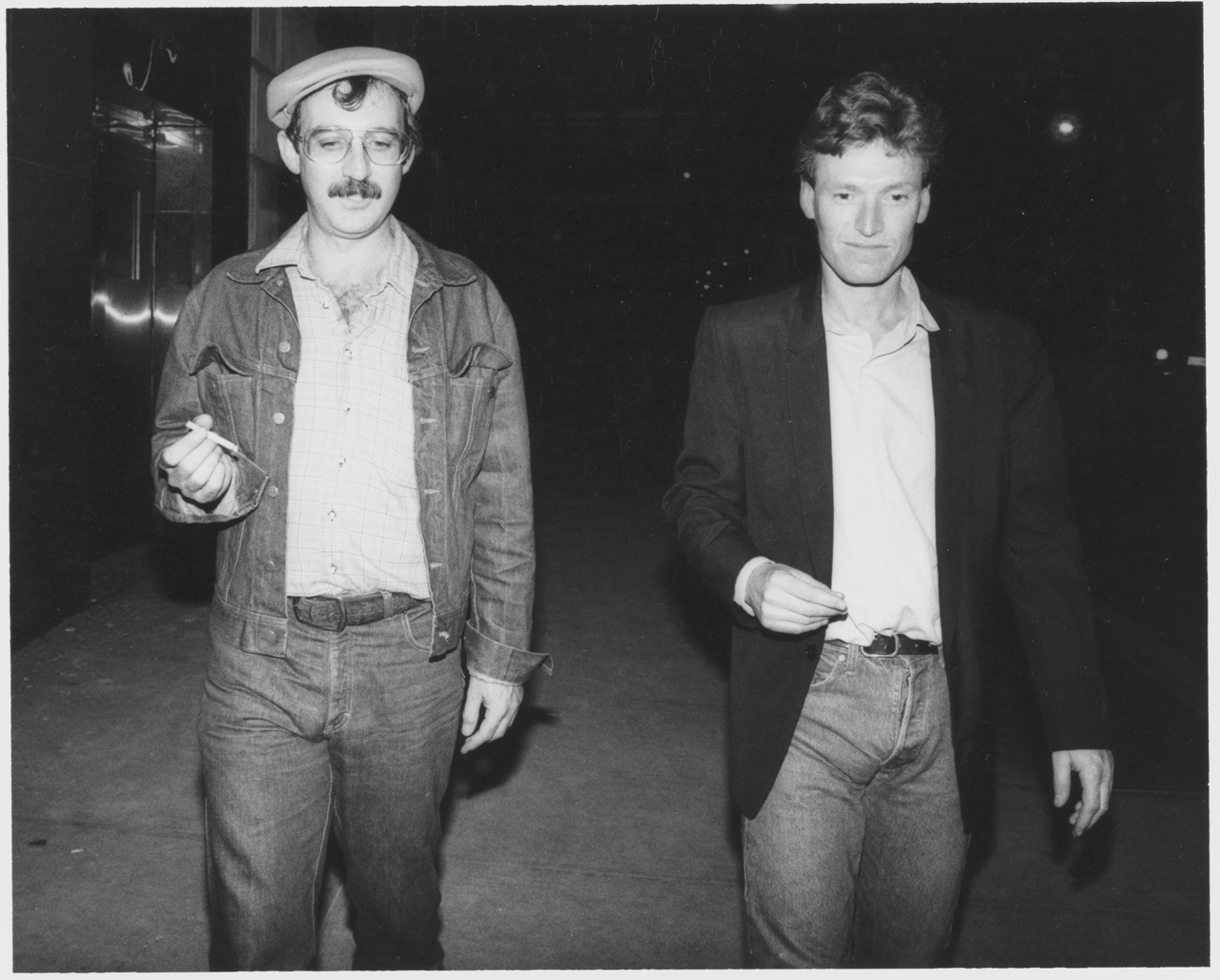

One of his ‘underground’ activities involved a musical liaison with the eccentric Bonzo Dog man Viv Stanshall. The pair had already co-written Dream Gerrard for Traffic’s swansong album and collaborated on Stanshall’s solo record Men Opening Umbrellas Ahead. They then concocted a soundtrack for a film version of Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast, hoping for financial backing. It never arrived.

They did, however, manage to funnel some of its ideas into Sir Henry At Rawlinson End, Stanshall’s surreal satire of upper-English mores that was eventually made into a film starring Trevor Howard in the title role.

“Viv was hilarious,” Winwood says, laughing. “He always sort of needed a straight man to do the musical things that he was wanting to do. And for a while I became that. We’d go into pubs and people’s houses and start off some kind of act. I’d play some music, he’d play a bit on his euphonium, then try to do conjuring tricks.”

In among all this larkery, in 1977 Winwood released his fairly underwhelming solo debut. His re-emergence as a major force didn’t happen for another three years, with the arrival of the belated follow-up, Arc Of A Diver. Stanshall co-wrote the title track, although more crucially the record marked the beginning of Winwood’s working partnership with Texan songwriter Will Jennings. Winwood also found himself restored to the business end of the charts in both the UK and US, with lead-off single While You See A Chance making the Billboard Top 10.

“At the end of the seventies my contract had run out, but I was still held by another option,” Winwood explains of the album’s inception. “So I decided that I was going to actually do everything on this record – play all the instruments, engineer it and write all the songs. I think the A&R department at Island thought I’d lost the plot and forgot about me a little bit. Then at some point they said: ‘Why don’t you at least work with someone who can help you with the lyrics?’ And they suggested Will. Lyrics were certainly always something I could do with help on, so I thought, yeah, I’ll work with this fella. I didn’t really know much about him or who he was, but we just hit it off. I started to work in a different way with Will. We discovered lots of ways of working together.”

Winwood’s 1982 album Talking Back To The Night made less of an impression, however. Aiming to repeat the DIY formula of Arc Of A Diver, the album instead felt under-produced and a little prosaic. Its relative lack of success, in addition to marital problems at home, led to a prolonged bout of soul-searching for Winwood. There were even rumours that he might quit music altogether.

“Was I thinking about giving it all up? Yeah, I was,” he reveals. “I was looking at what else was available – not that I could do anything else. But I was looking for something a little different.”

His solution was to switch managers and relocate to New York. He corralled a crack team of helpers – including co-producer Russ Titelman, James Taylor, Joe Walsh, Chaka Khan and Nile Rodgers – and returned with his biggest-selling solo record to date, 1986’s appropriately named Back In The High Life. The album won three Grammys, went triple-platinum and delivered his first ever US No.1, the ecstatic Higher Love. His writing partnership with Jennings produced further hits with Back In The High Life Again and The Finer Things.

In his late 30s, Winwood was suddenly a mainstream superstar. His sound may have taken on the requisite gloss and polish that the era tended to demand, but his absorption of disparate styles remained in keeping with his previous work. His new standing was compounded in 1988 by the equally big-hitting Roll With It, whose title track also topped the Billboard chart.

Winwood is quick to defend his output during the latter half of that decade. “The music industry was growing at a rate of knots, becoming huge and much more powerful,” he says. “In some ways I was getting led astray a little by the executives. I’m often accused, in that period, of moving much more towards pop. But Back In The High Life still has those elements of ethnic music, folk, jazz and all those things we were trying to do in Traffic. It’s just that Traffic had a lot of rougher edges, whereas this has that smooth eighties production technique. So I would maintain that I wasn’t particularly selling out. It was all down to the way it was recorded.”

It’s been a while since we heard from Steve Winwood on record. His last studio album, Nine Lives, was released in 2008. When he’s not at home with his family in his centuries-old manor house in the Cotswolds, he’s out on the road with his trusty band, playing dates around the US and Europe. It’s a vocation he takes very seriously, and tapes every show in order to assess the nuances of each performance.

“Technology has made that very easy to do now,” he says. “It’s just a sort of laptop set-up that we have. Sometimes we do it just for our own educational purposes, so we can listen afterwards and check on things to see how we’re sounding.”

Now, he has just released his first ever live solo collection, Winwood: Greatest Hits Live. The two-disc set serves as a glorious overview of his 50-plus years in the business, dipping freely into the back pages of the Spencer Davis Group, Traffic, Blind Faith and beyond. Most of what you might wish for is here, including Gimme Some Lovin’ and I’m A Man, Dear Mr. Fantasy, John Barleycorn and The Low Spark Of High Heeled Boys (arguably Traffic’s greatest moment), and While You See A Chance and Back In The High Life Again. Above all, the album reveals that Winwood is still fully engaged with all the things that make him great, chief among them being the finest white-soul voice of his generation.

“Over the last five or ten years we’ve been trying to hone our live show a little more,” he says. “A lot of the time I have to do certain stuff, or else people complain if I don’t play Can’t Find My Way Home or I’m A Man. So throughout the years we’ve tried to reinvent them or give them a slightly different twist, to keep ourselves interested if anything. And the audiences seem to like them too.

“I’ve been working for the last decade with José Neto, the Brazilian guitarist, and Richard Bailey, who’s Trinidadian. So we give it a sort of Latin/Brazilian feel, and sometimes with a little jazz in there. We thought it was about time we committed all this to record.”

Despite the subtle recalibrations of his back catalogue, it might be easy to surmise that Steve Winwood is riding out his days on past glories. But it turns out that he’s very much fixed on the future, and in a way that you might not expect. Nearly ten years on, he reveals that he’s finally begun work on a successor to Nine Lives.

“I’ve been quite into dance music lately,” he says. “There are some DJ/producers who are doing some very interesting stuff, so I’ve been looking at different ways to see how I can work with that. I’ve started putting some things down, and there are also lots of people in places like Brazil and Cuba that are doing things with dance music too. So that taps into the ethnic music side of things. I’m not sure whether it’ll actually be me or whether I might try to invent a third-party act, as it were. I’m just looking at all possibilities right now.

“There are so many different sub-genres that it’s sometimes difficult for people of my age to understand it,” the 69-year-old says laughing, “so I have to get my son to help me fathom it all out. But I do think that dance music takes as much playing and manipulation as any instrument does.

“I’m not one of those people who thinks, as a lot of my generation do, that the best music was made in the sixties and seventies and since then it’s all been going downhill. There’s some great stuff around, and the future holds a lot of very interesting things for me. I’m not finished yet.”