That day that rocked the world: the chaotic story of Status Quo's Live Aid

Live Aid in 1985 was perhaps the greatest rock festival of all, and Status Quo were there to open it

"It’s twelve o’clock in London; it’s seven o’clock in Philadelphia. This is Live Aid."

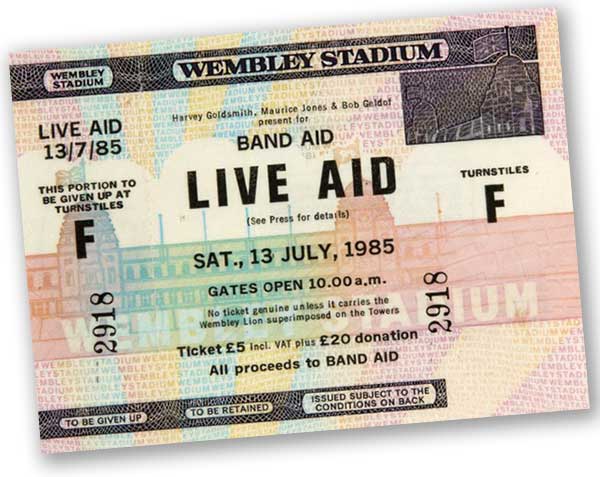

With this introduction by Richard Skinner still ringing in his ears, Tommy Vance made his own announcement: "And now, to start off sixteen hours of Live Aid, would you welcome, Status Quo!"

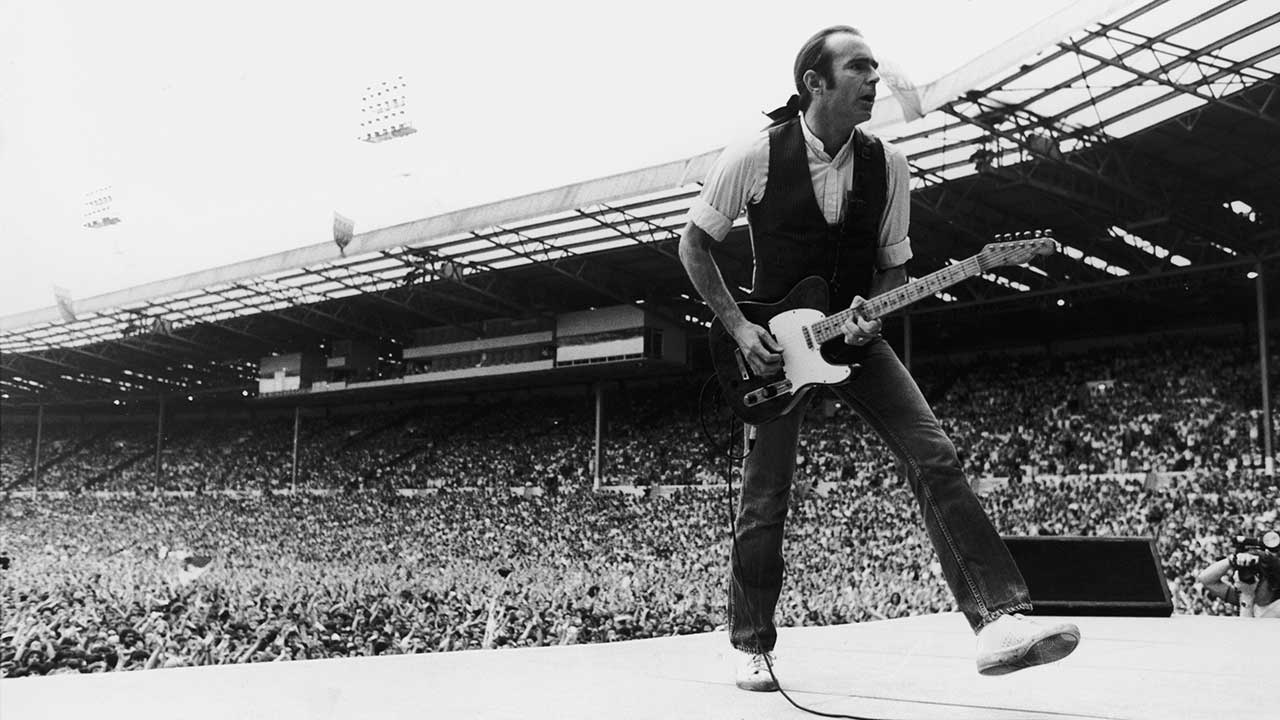

There was only one song the Quo could start with: Rockin’ All Over The World. It epitomised what the event was all about. It epitomised what Quo were all about. Within seconds the crowd was clapping and singing along raucously. Quo rocked on with Caroline and Don’t Waste My Time before saluting the crowd and walking off, just over 12 minutes later.

It was one of the shortest shows they’d ever played but it was probably the most significant. While Live Aid famously boosted the careers of several bands, most notably Queen and U2, it literally rescued Status Quo who scarcely existed as a group at that time. In fact, they had to be dragooned into playing the concert at all.

They were also somewhat miffed when they were first asked to open the show. It smacked of being bottom of the bill until they realised that it wasn’t that kind of show at all. In the event, being the first band to appear at Live Aid provided a publicity boost for Quo that no media campaign, however well planned and executed, could possibly have achieved.

After a slow, almost disbelieving start, interest in Live Aid took off at the beginning of July 1985 as the big names began to commit to the event – gradually at first and then in a flood: Paul McCartney, David Bowie, Led Zeppelin, Bob Dylan, Madonna, Mick Jagger, Elton John.

The BBC had announced that it would be screening the whole 10-hour show at Wembley and then crossing over to Philadelphia for another five hours – unprecedented coverage for a rock concert. All over Britain, millions of people organised their day around the telethon, cramming their Saturday chores into the morning and then settling down in front of the TV later on.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

It was a hot, sunny July day and as noon approached a palpable sense of expectancy gripped everyone, like waiting for the kick-off at the cup final. And then suddenly it was up and rockin’. All over the world. In America, countless kids who wouldn’t normally have clambered from their pits before 11am at the earliest set their alarms for seven, six and even five o’clock in the morning (in California) and staggered blearily to the TV set to be greeted by Quo’s bonhomie boogie.

A little early to be rockin’, maybe. But hey, rockin’ all over the world? I mean, these guys really are... It got better for Quo. Throughout the day the Live Aid concert was the main news item on just about every TV and radio station across the planet. And all of them mentioned four salient facts: Live Aid, Bob Geldof, Wembley Stadium and Status Quo.

By the end of the day, Quo’s place in history was assured. Who was the opening act at Live Aid? It’s been a staple poser of pub quizzes ever since. Too bad then that Rick Parfitt and Francis Rossi can only remember this momentous show through a haze of alcohol and cocaine, a popular rock’n’roll cocktail for the band back in the 80s.

“That whole period is a bit of a blur, frankly,” admitted Rossi. “I mean, I was pretty much out of it most of the time.”

In 1984, Quo had made their intentions clear with their ‘End Of The Road’ tour. After 20 years of touring they were removing themselves from the road to become just a recording band. Except that they weren’t even that. For a start, Alan Lancaster was now living in Australia.

“There was a lot of conflict within the band, particularly between Francis and Alan,” Parfitt confessed nearly 20 years later. “Feelings were running very high. I was trying to sit on the fence and coax them along but it had got to the point where it stopped being fun and just became a job.”

However, that hadn’t stopped Rick and Francis from partying on at every opportunity. And they were certainly in party-on mood for the recording of the Band Aid single, Do They Know It’s Christmas.

“We got a call from our manager saying: ‘Do you want to do this thing?’” remembered Parfitt. “And we knew Bob [Geldof] so we turned up. And there were all these 80s bands there. It was all a bit peculiar. But there was so much coke around, it was outrageous.”

“I’m not even sure I’d been to bed that night,” added Parfitt. “In those days it was still pretty rock’n’roll. You didn’t really pay too much attention to what you had to do the following day. If there were a few people around and the chance to get out of it, then you went for it!”

Rick and Francis may have looked somewhat incongruous among the 80s superstar haircuts milling around, but their little corner of the corridor soon became a popular place to hang out and they were getting on famously with everybody... except for Boy George acolyte Marilyn.

“Marilyn kept going in and out of the loo, but it was the girls’ loo,” Rossi chuckled. “And I got a bit fed up with it and said, ‘Look, why don’t you go into the men’s loo and sit down?’.”

“I think he was a little confused,” added Parfitt. “Things got a little more confused later when a toilet door came off its hinges in unexplained circumstances.” Francis claimed amnesia at this point, while Rick had a vague memory of a boot being applied to a door but says he doesn’t know whose boot. It’s also unclear what part a roll of gaffer tape may have played in the incident. But when the repair bill showed up at Quo’s office later it was apparently paid without question. By the time it was their turn to put down their vocals on the single Rick had already peaked.

“I blew it in a big way because I got completely shit-faced and ended up not being able to sing my part,” he admitted. “I tried, and under normal circumstances I would have been able to do it. But I was so out of my tree I couldn’t deal with it. So we kind of glossed over it and Francis sang his bit and then he sang my bit as well.”

Nevertheless, Rick was still able to claim a prime position when it came to the team photo.

“Rick was very good at that,” chuckled Rossi. “There was everybody jockeying for position in the photo and Rick elbowed himself in next to Sting.”

Rick’s even had the triple platinum disc up in his hall to prove it. “I’m very proud of it,” he said, “although I’m not sure I deserve it!”

Spending a day partying with the stars for Band Aid was one thing, but when Geldof asked them to play the Live Aid concert a few months later they had serious doubts.

“We told him, ‘We’re not really together as a band,’” Rossi recalled. “We said, ‘We’re under-rehearsed. We’re not going to be very good’. And Bob said, ‘It doesn’t matter a fuck what you sound like as long as you’re there’, which I thought was a bit too honest, but that’s Bob for you. He said that if he could get one or two of the older bands to commit then that would kick it all off. Because at that point he couldn’t get anyone to donate their services free of charge: Wembley, the police, British Telecom.

"And I must admit my first thought was that this guy was trying to feather his own nest. Obviously I regret that now because it became clear very quickly that he really did believe in it and he went with it and made everyone else aware of it.”

“Of course, nobody knew the impact it would have at the beginning,” Rossi continued, “but even then I was aware that most of big business just kept its head down and thought, ‘We’ll let these rock’n’roll dickheads do this and it will go away’. And it did. And that annoyed me.

"I mean, there was this British Airways TV advertisement that they’d spent £2 million on, just to tell us they were the world’s favourite airline. And I was thinking, ‘Who gives a shit?’ How often do you book a flight and say, ‘I want to travel on this airline?’. They could have done themselves a lot more favours by giving that money to Live Aid.

“And the oil companies, they could have donated their budget for that one day’s global advertising – all that stupid bollocks about how ‘our petrol makes your car go faster’ – and we could have raised twice as much. But they didn’t rise to it. And I find that a bit sad,” he concluded with a shrug.

Having agreed to appear, the Quo machine was cranked back into action. Alan Lancaster was contacted Down Under and he agreed to come over for the show. Meanwhile, other big names were now signing up as the event gathered momentum. Gradually a running order began to take shape. It was at that point that Rockin’ All Over The World started to manoeuvre Quo into pole position.

“I remember a discussion at which they wanted us either at the beginning or at the end,” recalled Rossi. “There was also an idea that we might play Rockin’ All Over The World with Paul McCartney. But our manager was aware of all the jockeying for position that could go on with this kind of mass bill – other managers saying, ‘My artist is not going on before so and so’ and all that stuff.”

What swung it was TV’s involvement. Once the BBC decided to televise Live Aid – and offer it to the rest of the world – the show took on another dimension. Mike Appleton, the producer of The Old Grey Whistle Test and the man in charge of organising the BBC’s coverage, had no doubts what he wanted to open up with.

“I wanted to start the whole thing with Rockin’ All Over The World,” he said. “With Status Quo as the opening act, it was the obvious song to start with. Not very subtle maybe, but it was exactly what the show was about. I think there was some resistance early on because I’m not sure that Quo wanted to go on first. And we were trying to pin down a running order. I think I was part of the forces of persuasion.”

Not that the band needed much persuading once the nature of the show became clear.

“I thought it was one of the best spots – to open the whole thing up,” said Parfitt. “It was something very special. Bob had already said that he wanted us at the beginning and we said, ‘Yeah, fine’. We didn’t want to be in the middle with McCartney and Queen because I think we would have been swallowed up.”

As soon as that decision was settled, Quo started reaping the benefit. With large chunks of the bill still being finalised, the BBC was looking for songs and names to promote the event. Some idea of the speed with which the whole thing came together can be seen from the cover of that week’s Radio Times which called it ‘The Global Juke-Box’ because the title ‘Live Aid’ hadn’t been confirmed by the time the magazine went to press. So the news that the show now had an opening act and an opening song was manna from heaven for the publicity-hungry BBC.

As July 13 drew ever closer, Francis and Rick found themselves doing interviews with TV, radio and newspapers, taking some of the burden off Bob Geldof. There was also a perfunctory rehearsal and a sound check.

“If we’d been fully aware of the significance of it I’d have made sure we did a proper rehearsal,” said Rossi. “But the feeling was, ‘We’re only going to be doing ten minutes so we can just knock that off’. And as far as I was concerned the band wasn’t going to be doing much any more, so who cares?”

On Saturday morning, the band gathered at a pub in Battersea before being helicoptered to Wembley Stadium. Looking out of the window as they came in to land, “you could see the crowd and the stadium was already packed. They were ready and waiting to go,” recalled Rossi.

“It was unbelievable,” added Parfitt. “We came towards the stadium at a couple of thousand feet, I guess, and then circled around. It was just fantastic to see all those people there.”

Backstage a strict schedule had been devised, giving each act use of a dressing room for 20 minutes before and after their spot before they were gently herded back towards the Hard Rock Café where everyone was hanging out. “What was amazing was that everyone went along with it,” said Parfitt. “We all knew that there were a lot of big acts there and a lot of egos flying about – or there could have been! But everyone knuckled down and got into the spirit of it. There were no silly games going on about wanting bigger dressing rooms or complaining about the flowers or whatever. It was just, get changed, do your job and get off.”

But even a hardened road act such as Quo realised that this was no ordinary gig as they made their way to the side of the stage a couple of minutes before noon.

“The atmosphere in the stadium was quite different to anything I’d ever experienced before,” Parfitt remembered. “The sun was shining and you could not have wished for a more vibrant setting. I remember the Royal Guards or whoever on stage playing the national anthem. And then the announcement from Tommy Vance...”

“I will never forget the feeling as we walked out on to that stage – it was just magical,” he continued. “It was real hairs-standing-up-on-the-back-of-the-neck stuff. When you walk out and you’ve got 80,000-odd people stretching into the distance, and then you become aware of the hundreds of cameras in front of you, and you start to take it all in... it was just breathtaking.”

“I think what was different about this audience,” Rossi said, “was that they weren’t just an audience that had come to see you. They felt they were a part of the whole event. Which they were. So there was this added euphoria in the place.”

“And then you realise,” said Parfitt, reliving the moment, “after you’ve been on for about five minutes, ‘Hang on, the whole world is watching this, literally billions of people’. And I’ll tell you what, it pulls you up for a second and you try not to miss a beat. You try not to fuck up.”

Watching Quo from the Royal Box was the man at the centre of it all, Bob Geldof, in the company of Prince Charles and Princess Diana. As he later recalled in his autobiography, Is That It?: “The noise of the crowd was incredible. As we came out it turned into a deafening roar. Half a dozen trumpeters and trombonists from a Guards regiment played a few bars of ‘God Save The Queen’, then Status Quo came out and went straight into Rockin’ All Over The World. It was a marvellous opening.

“Quo were well into it when Charles turned round and shouted in my ear, ‘We’re having a party at the Palace next week. I don’t think it will be like this, unfortunately’. ‘Who is it?’ ‘Bach and Handel.’ By the second number he was tapping his brogues spasmodically. ‘I think I’ve seen these chaps before.’ ‘Yes, they’re Status Quo. They did a Prince’s Trust for you.’ ‘That’s right. Birmingham, wasn’t it?’

“‘Did you ever like pop music as a kid?’ I quizzed the boogieing Prince. ‘Well, I did actually. It’s strange, because when I was younger people say I had an almost natural sense of rhythm,’ he said, clapping his hands, hopelessly out of time. ‘I’m going to have to go now because we’re on next,’ I said. ‘Yes, we’ll have to go soon,’ said the Prince. ‘We’re having lunch with my mother.’”

Almost before they’d got into their stride – Francis reckons they never did: “We were dreadful” – Quo were off and the Style Council were being hustled on to the other side of the stage. There was the obligatory instant post-match photo and interview that neither of them can remember, then it was back to the dressing room and swiftly out to the Hard Rock Café where they could relax while everybody else was still in various states of preparation.

I think you can guess what’s coming next. In fact the band are already ahead of you. The rest of the day is a blur, although for some reason David Bowie keeps cropping up in what fragments of memory survive.

“Bob said, ‘OK, go off and do whatever you want, and be back here for the finale’,” recalled Parfitt. “So I jumped back on the helicopter – with David Bowie, funnily enough – and flew back to Battersea, which was near where I lived at the time. And my wife and I just disappeared into the local pub where it was all, ‘Hello, Parfitt. Just been watching you on the telly. What are you having?’. And we watched the show there and got completely shit-faced until it was time to go back.”

Francis decided to stay backstage at the stadium, but the result was the same. “It was the coke era back then. I don’t think anyone I knew wasn’t doing coke. And I was drinking as well. We were sitting on a table up at the back. And I remember everybody had these huge great mobiles at the time. And none of them worked. There was no reception. That was funny.

“And I remember looking over at Elvis Costello. My son has always been a fan. But [Elvis] obviously hated me. I was going, ‘Hi’ and he was just blanking me. And I thought, ‘Well, fine’. We were very unfashionable. Always have been.

“The other strange thing was that I’d seen David Bowie earlier in the day and I saw him again late in the evening when we were all discussing what to do for the finale. And he looked immaculate. So I said, ‘How do you do that?’, and he leaned over and said, very conspiratorially, ‘Ah, ha’. And I’ve never figured out quite what he meant by that. Everyone else had been sitting in the same clothes all day and looking the worse for drink. But he just looked so good.

“Ever since then I’ve always been aware of how I look. David Bowie did that to me, the bastard!

“Finally,” he added, “we were all gathered behind the stage, waiting to go on and I was sitting on this table with Steve Van Zandt and David Bowie. Suddenly the lights went out for some reason and this table collapsed. And we all had to scramble up and get out on stage for the finale. That’s all I remember.”

By now, Rick was in an even worse state. “When I got back there I was totally gone. I had my missus with me as well and I said, ‘You’ve got to come on stage’, and she was saying, ‘No, no!’. I said, ‘Come on, nobody will mind’, so there we are, the pair of us over by Elton who’s tinkling the ivories, standing there with huge grins on our faces.”

It took a day or so for the magnitude of the concert to sink in. It took a while longer for Francis and Rick to realise how invigorated they’d been by playing live again and decide to revive Quo as a proper band. It took a lot of hassles and a new line-up to put that into practice. But when they finally emerged, Quo found that Live Aid had transformed their reputation, and they were now able to bask in their status as the elder statesmen of rock. Household names, no less.

“When I think back now to that first conversation with Geldof,” said Parfitt. “Us saying, ‘We can’t do it. We won’t be good enough’, and Bob saying ‘Just be there. Just do it’. If we’d said no we’d have looked back forever and thought, ‘My God, we should have done that’. I’m so pleased we mustered ourselves for that day. It was an honour."

Hugh Fielder has been writing about music for 50 years. Actually 61 if you include the essay he wrote about the Rolling Stones in exchange for taking time off school to see them at the Ipswich Gaumont in 1964. He was news editor of Sounds magazine from 1975 to 1992 and editor of Tower Records Top magazine from 1992 to 2001. Since then he has been freelance. He has interviewed the great, the good and the not so good and written books about some of them. His favourite possession is a piece of columnar basalt he brought back from Iceland.