In 2011 a dispute between former members of The Nice spilled into the public domain after guitarist Davy O’List discussed his part in their 1968 debut album The Thoughts of Emerlist Davjack. Upset by his comments, former bandmates Keith Emerson (1944-2016) and Lee Jackson dropped into the Prog office to give their account of proceedings.

Keith Emerson and Lee Jackson have a professional and personal relationship that stretches back close to the 50s. This comes through with the relaxed banter in which the keyboard player and bassist/vocalist – whose most fruitful musical alliance came at the end of the 1960s in The Nice – indulge:

Emerson: “Quite a few major names turned up to see The Nice. The jazz greats Johnny Dankworth and Cleo Laine, Nico from The Velvet Underground...”

Jackson: “Nico fancied you.”

Emerson: “What? I wish I’d known!”

Jackson: “You were too busy with little Cleo. Mind you, Nico wasn’t alone. Salvador Dalí and Andy Warhol turned up to a gig together and they wanted a piece of you.”

The pair have been brought together through a mutual disappointment over comments made by Nice guitarist Davy O’List two issues ago in Prog, when he talked up his importance in the recording of the band’s 1967 debut album, The Thoughts Of Emerlist Davjack.

But if setting the record straight was initially the reason they were anxious to talk, things quickly open up into a far wider discussion on the story of a band who were barely together for two years – yet had a major impact.

The pair first worked together in mid-60s R&B band The T-Bones. From there, Emerson briefly joined The VIPs, before fate changed his life.

“I was doing a gig with The VIPs in Paris in 1967, when a road manager friend of mine named Mickey Oram said he wanted me to meet this American soul singer P.P. Arnold. She had a deal with a new label called Immediate [run by Rolling Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham] and was looking for somebody to put together a band around her.”

Emerson took on the task, bringing in Jackson – who’d previously worked with John Mayall and Eric Clapton – and also a young guitarist getting a reputation for himself. “It was a singer called Richard Shirman who recommended Davy to me. They’d worked together in a band called The Attack.”

Drummer Ian Hague completed the original line-up, although he was quickly replaced by Brian Davison. All they now needed was a name. “There was an American TV comedian at the time called Lord Buckley,” explains Jackson. “He had a character called Jesus Of Nazareth... The Nazz, and that was going to be our name.”

“But Todd Rundgren already had a band called Nazz,” adds Emerson. “So Pat [PP Arnold] suggested we call ourselves The Nice. She came from the South Central area of Los Angeles, and her accent was so strong she thought The Nice was just an English pronunciation of The Nazz!”

The early days of the band were spent backing Arnold, but they did get to do a 20-minute set on their own every night before the singer came onstage. And the young band soon got attention in their own right. “We realised early on that you could play what you wanted,” recalls Jackson. “All you had to do was dress like the pop stars of the day.”

The big break came when Arnold’s visa ran out and she had to go back to the States. Emerson was called in for a meeting with Oldham. “I expected him to tell me we were being fired. Instead, he offered the band a recording deal – effectively taking over from Pat. He wanted us to go into Olympic Studios in London and do an album. But he insisted it had to be a record of original songs, although our set at the time was all covers.

“Andrew asked if we were songwriters. So of course I said we were, and then I had to go away and figure out how the hell you wrote songs! I’d written some pieces when I was 10 years old, but nothing since.”

Keith intimidated guitarists. That’s why Steve Howe went to Yes… he wasn’t so intimidated by Rick Wakeman!

Lee Jackson

Emerson –together with Jackson – was determined to rise to the occasion. And what they came up with was not only of a very high standard, but also innovative and original. The first song Emerson wrote was Azrial, the B-side of debut single, The Thoughts Of Emerlist Davjack. “I incorporated a piece from Rachmaninoff called Prelude In C# Minor – and this was at the start of classical music infiltrating into rock.”

The first album contained just one cover, Dave Brubek’s jazz standard Blue Rondo A La Turk, which was retitled Rondo. “We’d been doing it since the days of T-Bones,” says Jackson. “I’d come up with the galloping arrangement after watching a cavalry charge in the classic silent movie Alexander Nevsky.”

“I met Brubek recently, and he gave me his autograph,” adds Emerson. “He’d signed it: ‘Thank you Keith for your 4/4 version. Which I cannot play’.”

In the summer of 1968, The Nice released their controversial cover of Leonard Bernstein’s America as a single. It would be the band’s biggest hit, reaching Number 21 in the UK charts, and also led to a lifetime ban at the Royal Albert Hall, after Emerson had burnt the Stars And Stripes onstage during a performance.

Meanwhile, O’List was becoming increasingly erratic. “He’d always been a little weird, but finally went over the edge when he had a drink spiked while we were in Los Angeles,” says Jackson. “From then on he missed a lot of rehearsals and even some gigs.” Eventually, the band decided to fire him.

“He took it really badly,” sighs Emerson. “But we had no choice. Besides, he should take satisfaction from the fact that we never replaced him. We did try out Steve Howe, but then he left for Yes. By that time, though, the band was working really well as a trio, so we didn’t need another guitarist.”

When they found I was gonna be working with Greg Lake and Carl Palmer they said, ‘Good luck. You’ll need it!’

Keith Emerson

“I think Keith intimidated guitarists,” smirks Jackson. “That’s why Steve Howe went to Yes. He wasn’t so intimidated by Rick Wakeman!”

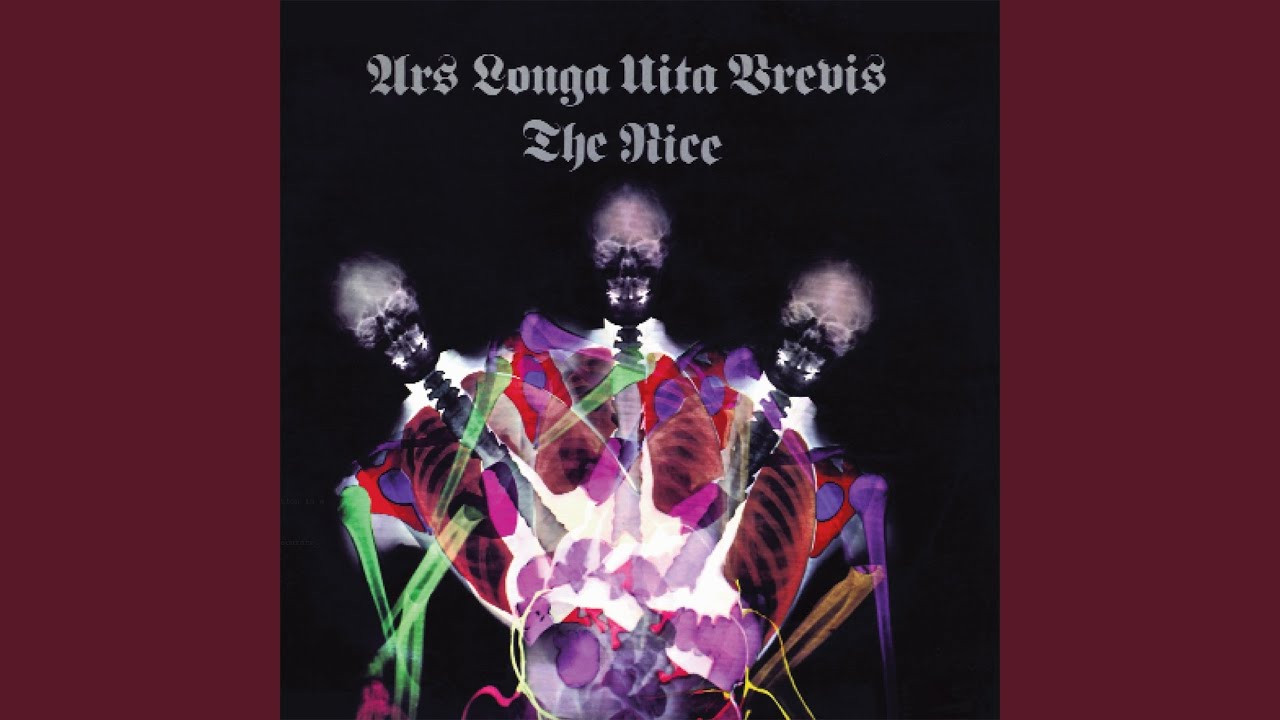

By the end of 1969, the trio had two more albums to their name: Ars Longa Vita Brevis and Everything As Nice As Mother Makes It (the latter also known simply as Nice). They’d also recorded a live performance of the Five Bridges Suite at the Fairfield Halls in Croydon (October 17, 1969), although it wasn’t released until 1970.

Emerson had also developed his remarkable stage show, stabbing his keyboards with knives. “I’d seen this crazy guy called Don Shinn playing the organ at The Marquee, and using a screwdriver. I thought I could go further with knives, both to hold down the notes and also to get the sound of an air raid siren.”

It was Motörhead’s Lemmy – Jackson’s bass tech at the time – who suggested Emerson should use the sort of knives for which he would become famous. “At first I bought a curved Turkish dagger. But Lemmy said in that gruff voice of his, ‘What you want are Hitler Youth daggers. If you’re gonna use a knife, use a proper one!’”

But by the start of 1970, the band were over. “I was impetuous,” admits Emerson now. “I felt we should all move on and explore other dimensions in music. When I broke the news to Lee, he took it okay. But Brian was very upset. And when they found out who I was gonna be working with – Greg Lake and Carl Palmer – they both said, ‘Good luck. You’ll need it!’.”

The Nice were among the pioneers of progressive music. In fact, the term grew up around them, as Jackson recalls. “We were called an underground band back then, and I thought of us as playing contemporary music. Now, of course, everyone sees it as prog rock. And we were certainly among the first.”

We showed you could play interesting, challenging music, without having to compromise

Keith Emerson

The band also knew how to enjoy themselves on tour. Forget about prog rockers being serious musicians who acted like monks... “The birth control pill had just been invented, so that gave us a lot of scope for being bad boys,” laughs Emerson. “We all behaved badly in that respect – but Lee was worse than all of us. He taught me a trick or two.”

“We were also, I reckon, the only band of the type to have screaming girls at a gig,” adds Jackson. “It happened at The Marquee, when three girls were at the front screaming at Keith all night. It was only later we found out they’d been paid to do it by our manager, Tony Stratton Smith!”

Musically inspired, The Nice flickered only briefly. They did reunite in 2002, but the death of Davison six years later put paid to any chance of it happening again. However, Emerson and Jackson are both proud of what their band achieved. “I think our lasting legacy was that we showed you could play interesting, challenging music, without having to compromise,” says the keyboard maestro.

Currently, Emerson is planning more recording and possible shows with his own group, The Keith Emerson Band. He’s also heavily involved in the revamping of the ELP back catalogue, which will all be reissued by Sony in the coming months.

Jackson plays local gigs in Northampton, where he lives. But these are no more than occasional bands, with no suggestion of anything serious coming of them.

Would the two ever work together again?

“If he asks me, I’d love to do something with Keith,” admits Jackson.

“We get on well, musically and personally, so never say never,” concludes Emerson.