THIS WAS (1968)

For many new bands in the late 1960s, playing the blues was a matter of expediency, and the fledgling Jethro Tull’s presciently titled debut This Was was effectively a record of 1968’s live set. The late Glenn Cornick thought it “naïve” and “amateurish”, but therein lies its enduring appeal. In contrast to the ‘conventional’ white man’s blues of the likes of John Mayall, Fleetwood Mac and Chicken Shack, This Was’ exciting blues-jazz-rock hybrid, driven by the distinctive rolling licks of Mick Abrahams and the breathy, frantic Roland Kirk-esque flute of Ian Anderson, was – and is – startlingly unique. It’s unrepresentative of what Tull became, but it remains a fascinating time capsule.

STAND UP (1969)

To many, including Ian Anderson, this is the first real Tull album. With rookie guitarist Martin Barre having replaced the staunch bluesman Mick Abrahams, Anderson had free rein to develop his own direction for the band. Elements of the blues remained in the likes of A New Day Yesterday, but elsewhere, the introduction of mandolins and balalaikas signalled a broadening of influences, drawing on folk, Middle Eastern and even classical music, most notably on a jazzed-up version of Bach’s Bourée. From eyeball-bulging rockers (Nothing Is Easy, For A Thousand Mothers) to whimsical acoustic love songs (Look Into The Sun, Reasons For Waiting), the Tull blueprint was being formulated.

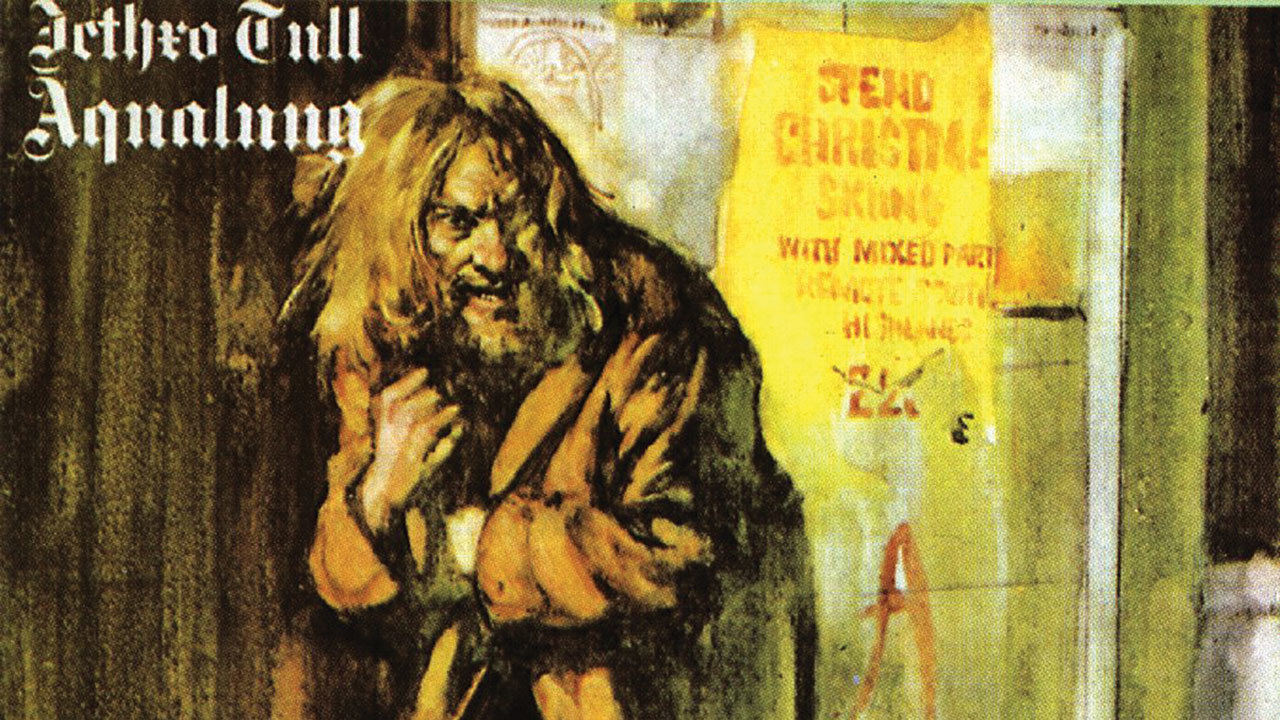

AQUALUNG (1971)

The biggie. An extraordinarily dynamic album, kick-started by the title track’s thundering riff, followed by timeless classic rockers (Cross-Eyed Mary, My God) and interspersed with short acoustic ditties that could have come from the Roy Harper songbook (Cheap Day Return, Wond’ring Aloud). And Locomotive Breath remains the best live encore written by anyone, anywhere, ever. Lyrically, side one painted a few portraits of society’s oddballs and outcasts, while some of side two explored themes related to organised religion, leading the critics to label it a concept album. It wasn’t. But as a collection of literate work, as well as musical songs, it was seminal Jethro Tull – fist-waving, sensitive intelligence.

THICK AS A BRICK (1972)

You want a concept album? You’ve got it. A continuous (apart from flipping the LP over half way) 44-minute piece exploring societal constraints on the individual, purportedly written by child prodigy Gerald Bostock, it came housed in an elaborate 12-page spoof local newspaper. This was groundbreaking stuff, all delivered (especially on stage) with a healthy dose of Tull humour. By now, Anderson and Barre had been joined by Blackpool buddies John Evan, Barrie Barlow and Jeffrey Hammond-Hammond, a line-up that was to last some five years. Evan’s keyboards are a particular feature of this intricate, clever, quirky, dynamic, uplifting rock symphony. Prog rock? Yep!

A PASSION PLAY (1973)

The Marmite album. Another 44-minute epic opus, featuring, strangely for Tull, considerably more alto sax than flute, a myriad of ever-changing time-signatures, and cryptic lyrics charting a journey into the afterlife, broken only by the interlude of the Lewis Carroll-type nonsense poem The Story Of The Hare Who Lost His Spectacles, which tends to date the album somewhat. For some, A Passion Play is a work of genius and it will always be their favourite Tull album because of its complex intensity. For others, it’s nothing more than overblown and slightly pompous too-prog rock by half! Thanks to the over indulgence with that saxophone, writer and composer Ian Anderson is very much in the latter camp these days…

MINSTREL IN THE GALLERY (1975)

In 1975, the band had decamped to a mobile recording studio in Monte Carlo, where, as Ian Anderson later lamented, the distractions of the nearby beach proved too strong for some members of the group. He often found himself working alone in the studio, producing a quasi-solo album – arguably actually a positive result. Highlights are the 16-minute suite Baker Street Muse (geddit?) and the achingly gorgeous Requiem. With the alto sax ditched, electric and acoustic guitars, along with the flute, were once again the signature sounds, augmented throughout by a string quartet. Overall, this may be the most quintessential of Tull albums.

SONGS FROM THE WOOD (1977)

Ian Anderson’s move from the city to the country was the catalyst for a change in musical direction and, as the title Songs From The Wood suggests, this album tips its hat towards folk rock. However, despite the use of medieval percussion, such as nakers and a tabor, tin whistles and – surely a first for any rock band, however eclectic – a portative pipe organ, this was not the hey-nonny-no folk rock of your Steeleye Spans et al. Lyrically, some of the songs draw on English folklore myths and legends (Jack In The Green, Cup Of Wonder), but there are also vignettes of modern country dwellers and dwelling (Hunting Girl, Fire At Midnight). Classic rock with a folk feel.

UNDER WRAPS (1984)

Despite arguably being Tull’s least popular album, Under Wraps is here because it’s a prime example of the band not being afraid to experiment – in this case, with 80s electronica. The majority of the tracks were co-written with new recruit Peter-John Vettese, a keyboard virtuoso, and were drenched with synths and – gulp – a drum machine. While the original LP contained some excellent songs beneath all those techno sounds (Later, That Same Evening, Paparazzi), subsequent CD reissues with added contemporary bonus tracks render it a bit of a slog. Perhaps Steven Wilson could be persuaded to remix the album using a freshly recorded human drum track? File under ‘very much of its time’. With a flute.

CREST OF A KNAVE (1987)

The controversial one, having been awarded a Grammy – not in the as-yet-uninvented flute rock category, but in the hard rock/heavy metal category, much to the dismay of fellow nominees Metallica. Tull have never been metal, but they’ve always rocked hard, and if their 1987 sound was more mature than the freneticism of 1969, then electric guitar-driven tracks such as Steel Monkey and Raising Steam still kicked ass alongside the more measured live perennials Budapest and Farm On The Freeway. Ian Anderson’s lower-tone vocals, necessitated by a recent throat injury, and Martin Barre’s acquisition of a Hamer guitar, led to comparisons with Dire Straits. The single Said She Was A Dancer maybe, but the rest? Nah.

ROOTS TO BRANCHES (1995)

After flirting with the blues again on 1991’s Catfish Rising, for their penultimate studio album Tull reverted to their tried and trusted, hard-to-pigeonhole eclecticism, in what Anderson described as a nod back to the approach the band had taken with Stand Up. Rare And Precious Chain, This Free Will and Dangerous Veils were born somewhere between Cairo, Delhi and psychedelia; Out Of The Noise is kitchen sink jazz rock; Valley and Beside Myself gradually reach a crescendo from delicate acoustic openings; and the dying song At Last, Forever will get you blubbing. Overall, a laudable return to form, with the uniquely unmistakable and wholly diverse Jethro Tull sound. Whatever that is…

Ian Anderson on Jethro Tull and the importance of looking forward

Martin Barre: “Ian and I don't communicate – we've gone our separate ways"