79) Roger Daltrey: The boy from Acton, that’s who…

One of The Who’s two surviving members, frontman Daltrey is a working class street-fighting man, who dodged a life of hard factory graft to become the prototype rock god. His bare chested onstage posturing at Woodstock cleared a path for Led Zep’s Robert Plant. Before all that occurred, Daltrey cut his teeth as a cracking rhythm and blues shouter on The Who’s ’65 debut album My Generation, where he tackled James Brown’s epic Please Please Please and Bo Diddley’s I’m A Man with lung-shredding conviction. EM

78) Alvin Lee: Boy, could he play guitar… and sing

Like Hendrix, Clapton, Peter Green and many other guitar heroes, Alvin Lee’s vocal chops have been overshadowed by his six-string prowess. It was his blistering performance of I’m Going Home at the Woodstock hippie fest that earned Lee the title “the fastest guitar in the west” and made him and his band Ten Years After famous. But the boy could sing too. For blues fans, the first three TYA albums – the self-titled debut, Spinal Tap-esque Stonedhenge and Ssssh – are full of great vocal performances. A cover of Sonny Boy Williamson’s Good Morning, Little Schoolgirl on Ssssh is a highlight. EM

77) Mick Jagger: Never mind the lips. Listen to that voice…

It’s apt that The Rolling Stones’ logo is a flapping great gob. After all, Mick Jagger’s mouth – on which John Pasche’s classic design was based – has been the band’s trump-card since 1962, spitting out arguably the best damn white-boy blues this side of the Atlantic.

The most celebrated Jagger vocal performances – Sympathy For The Devil, let’s say, or (I Can’t Get No) Satisfaction – are an extension of the man’s personality: cocksure, irreverent, sexual, patently in thrall to America, but at the same time quintessentially British. The drawled hedonism of Rocks Off and the chippy honk of Can’t You Hear Me Knocking are still electrifying, but some of our favourite Mick moments are when he gets serious, whether on the apocalyptic Gimme Shelter or the bruised intro of Let It Loose.

Even now, at 72, he can still do the business, working the crowd like an aerobics instructor and hitting the notes on the bullseye (while other frontmen his age would be wheezing like a thirsty bulldog). Make no mistake: Mick Jagger’s mouth is a national treasure. Even if he sometimes sounds like he’s singing through his nose… HY

76) John Mayer: The accidental singer.

The Connecticut songwriter admits that singing was an afterthought – “I just wanted to be the best guitar player” – but there’s a sense of casual brilliance every time he takes a vocal, from the wistful kiss-off of All We Ever Do Is Say Goodbye to the vulnerable glide of Gravity. Four years ago, Mayer was informed that “cancer would be easier to get rid of” than repairing the granuloma in his throat. The bandleader beat that bleak diagnosis, thank God, reminding us of his heartfelt delivery on recent cuts such as the joyous Wildfire and the sparse Dear Marie. HY

75) Seasick Steve: Wit and wisdom behind the beard.

“For me, the story was always the important thing,” the bushy journeyman once noted – and it’s the way he tells ’em, from Dog House Boogie’s slurred memories of a broken home, to Heart Full Of Scars’ falsetto ruminations on his 2004 heart attack. Given that Steve often tracks with a drink in one hand and has a fast-and-loose approach to production, he’s not the most polished vocalist, but the scratches and dings on that voice box are part of the charm. As he says on Sonic Soul Boogie: ‘You either gonna feel it, baby – or you don’t…’ HY

74) Alexis Korner: The “Korner-stone” – if you will – of the British blues scene.

It would be easier to name the musicians who Korner didn’t influence in the 1960s. Korner helped to bring together The Rolling Stones, Cream and Led Zeppelin, among others. As a singer, he influenced everyone from Mick Jagger to Rod Stewart.

His early recordings with Blues Incorporated set the benchmark for a whole generation. And that deep oil well of a voice of his also made Korner the perfect voiceover artist and radio presenter, earning him regular slots on Radio 1. In your face, Ron Burgundy! JHai

73) Jack Bruce: The cream of the crop.

Eric Clapton may be Cream’s most celebrated alumnus, but from 1966, the late Scottish bassist was the trio’s salesman, his fingers manically thrubbing the strings of that Gibson EB-3 while he delivered vocals of rare soul. Singing most of the lead, Bruce could be ballsy (on White Room) or vulnerable (revisit that quavering vocal on We’re Going Wrong), but he was also a sympathetic team player, turning to Pete Brown for mind-expanding lyrics and sharing the mic with Clapton on Sunshine Of Your Love and I Feel Free. HY

72) Eric Burdon: The Geordie with raw passion.

Though born in Newcastle, Burdon would have liked to have been an American blues singer. Influenced by Joe Turner, Jimmy Witherspoon, Billie Holiday, Joe Williams, Chuck Berry and Ray Charles, Burdon, as vocalist of The Animals, became one of British R&B’s great voices, a blues shouter whose guttural delivery was filled with raw emotion. The Animals’ chart topping 1964 cover of folk song The House Of The Rising Sun was a perfect vehicle for his gritty delivery. Further hits included a bellowing reading of Nina Simone’s Don’t Let Me Be Misunderstood that he made his own. JH

71) James Brown: The hardest working tonsils in showbusiness.

“Most associate James Brown with inventing funk in the late 60s and 70s, but he was also one of the great blues and soul singers when he started out. Listen to Live At The Apollo from 1962. I first got a copy of that when I was 20 and I was blown away by his singing on it. It was raw, tough and incredibly passionate, and so effortless and natural too. He could go from a scorching drop-to-his-knees soul ballad with feeling like I’ll Go Crazy or Please Please Please or Try Me to an R&B rave-up like Night Train. He could do a perfect soul scream, he could convey anguish and pain and the fact that that album was recorded live, that made it all the more impressive.”

70) Paul Butterfield: The singer who helped Americans fall in love with the blues again.

Butterfield played a key role in bringing the world of Chicago blues to white American audiences. Listen to him take the ball and run with it on Born In Chicago and then appreciate how he opened the doors for later artists, such as Blues Traveler. JHai

69) Johnny Copeland: The Texas Tornado with a voice like a hurricane.

Like so many musicians, Copeland was heavily influenced by T-Bone Walker and had a rich, soulful voice, which could handle anything that was thrown at him. He helped shape the Texas blues sound, which can still be heard today through artists like Kenny Wayne Shepherd and, of course, Copeland’s daughter, Shemekia, who is one of the hottest acts out there today. JHai

68) Jimi Hendrix: ‘Scuse us, we won’t diss this guy…

He might be the greatest guitarist of all time but Jimi Hendrix disliked his own singing voice. “We had a constant row in the studio,” his manager Chas Chandler said, about “where his voice should be in the mix. He always wanted to have his voice buried and I always wanted to bring it forward. He was saying, ‘I’ve got a terrible voice, I’ve got a terrible voice.’” But Jimi’s vocals on songs like Hey Joe, All Along The Watchtower, Stone Free etc, suit the mood of each track perfectly. It was always a perfect duet with his Fender Stratocaster. EM

67) Jack White: Blues brilliance from a White Stripe.

He once claimed to “attack” his guitar, and the same goes when he squares up to the mic. Sure, White is capable of tenderness – revisit the sweet We’re Going To Be Friends – but the classics find him screaming like a banshee that’s hit its thumb with a hammer, in a holler pitched between primal blues and spittle-flecked punk.

If Robert Cray’s buffed mahogany croon is at one end of the spectrum, then White’s voice is slammed hard to the other. The ragged falsetto of Blue Orchid. The passive-aggression of I Just Don’t Know What To Do With Myself. The simmering threat of Seven Nation Army. As White told NPR, singing is the only time he expresses himself: “I can’t stand my speaking voice. I’m happier singing than I am speaking.”

Just as he’s militant about his guitar tones, so White has firm opinions on how a vocal should be recorded, choosing to split the mic signal, with one line running clean to the desk and the other to a vintage valve amp for maximum spit-and-grit. “He likes that slammed vocal sound,” notes engineer Joshua V Smith.

Post-White Stripes, White seemed to step back from his role as a vocalist, splitting duties with Brendan Benson in The Raconteurs and warming the drum stool for The Dead Weather. So it’s been a revelation to hear him leading the line once again with solo albums Blunderbuss and Lazaretto. Long may he shriek. HY

66) Walter Trout: The blues’ greatest survival story.

Given that Walter Trout spent half of the 80s unable to speak, it was a revelation when the cleaned-up guitarist quit the Bluesbreakers in 1989 and unveiled that fruity bark of a singing voice. In reality, he’d already fronted early New Jersey outfit Wilmont Mews, but stepped away from the mic upon switching coasts in 1974. “It was my dream to have my own band when I got to California,” he recalled. “Then I started getting these gigs as a sideman…”

Like his blazing Stratocaster solos, Trout’s voice is an evocative cry from the heart, that east coast drawl still palpable as he rages against feckless politicians and crap TV, or ruminates on that broken childhood. There’s a warmth and body to his vocal delivery, though he’s been known to slip into the upper register, as on Song For A Wanderer. “A lot of people hate it,” he admits of the song, “because I sing in falsetto, and they don’t get it.”

In recent times, ravaged by liver cirrhosis and dehydrated by medication, it seemed that Trout’s voice might be lost: on 2014’s The Blues Came Callin’, by his own admission, he could only manage a parched whisper (“The illness has changed my voice and taken a lot of it away”). Given that, there were few more heartening sounds than the bluesman’s full-throated return on last year’s restorative Battle Scars: the sound of a man shouting his resurrection from the rooftops. HY

65) Jim Morrison: Cool personified by the lizard king.

The Doors’ ‘lizard king’ was the ultimate achingly cool lead singer. But for all his outward bravado, Jim Morrison was initially insecure about his voice.

“Jim was not a trained vocalist,” says Doors guitarist Robby Krieger. “But the more The Doors played together the better Jim became.”

Morrison ended up with two vocal gears: the bluesy hard rock bellow of Roadhouse Blues, and the deep baritone croon (think: a stoned, more lascivious Frank Sinatra) heard on Touch Me and Indian Summer. Both styles would later influence Iggy Pop, Bono and Morrison’s Doors understudy, The Cult’s Ian Astbury.

“I’ve always believed that by not being able to copy anyone else, Jim found his own style,” said Ray Manzarek, keyboardist, who thought Morrison’s greatest strength was “validating other people’s songs”.

Unable to mimic his bandmates’ voices, he had to re-interpret their material, which always improved it. “He did this on every one of my songs, especially Light My Fire,” claims Robby. “There’s a scene in [Oliver Stone’s] The Doors movie where I come in with Light My Fire and [actor] Frank Whaley, who played me in the movie, sang the song exactly like I sang it to Jim in real life. Then, in the film, you see Jim sing it. And that’s how it really happened. It was the same with Love Me Two Times. Jim couldn’t sing anything the way I sang it, so he did it his way. He made every Doors song better.” MB

64) Gregg Allman: The Ramblin’ Man who put the soul into southern rock.

Allman has influenced countless southern rock singers over the years, and many have copied his soulful tones. But you can’t beat the original, particularly Midnight Rider and Statesboro Blues from the Allman Brothers’ seminal 1971 album At Fillmore East. JHai

63) Clarence ‘Gatemouth’ Brown: From the bayou to the blues.

Born in Louisiana but raised in Texas, Brown could sing anything from straight ahead blues numbers to country and Cajun music. Legend has it he was christened ‘Gatemouth’ by a school teacher on account of his deep voice, which served him well in a career that spanned 50 years, and saw him record with all the greats. JHai

62) Little Walter: The Chicago blues harp king had another instrument too: his voice.

Arguably, Marion “Little Walter” Jacobs’ true “voice” was his harmonica, and he revolutionised its use in the blues by experimenting with distortion and echo. When he did sing, though, the results were equally effective and he emerged as a versatile vocalist: on My Babe (1955) he’s tough and bragging, on Blues With A Feeling (1953) his vocal takes on a wounded edge, and it’s incredibly soulful, too. Paul Butterfield, John Mayall and Junior Wells are just a few who were influenced. JH

61) Jeff Healey: From blues to jazz and back again.

The blind Canadian guitarist shot to fame in the late 80s with his debut album See The Light, boosted by the hit ballad Angel Eyes. Much of the early attention focused on his unorthodox guitar technique – he played his Stratocaster laid flat on his lap – but he possessed a distinctive, plaintive voice.

At the start of the 2000s he switched from blues to jazz and played both guitar and trumpet, captured on It’s Tight Like That and 2010’s posthumous Last Call. Vocally, Healey proved just as adept with ragtime and Dixieland as he was with blues. DW

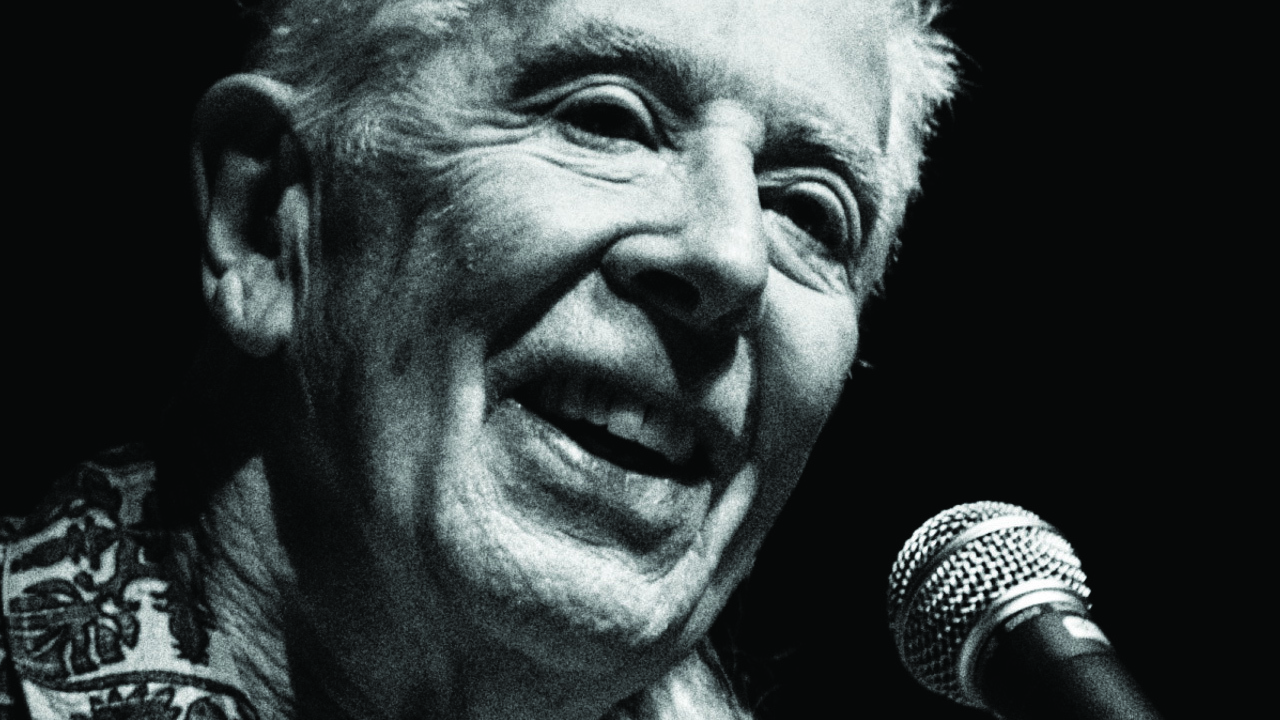

60) John Mayall: All hail the original British blues rocker.

As one of the grandfathers of the British blues scene, Mayall has drawn the roadmap for successive generations of singers to follow. In the early days, Mayall toured with the likes of John Lee Hooker, T-Bone Walker and Sonny Boy Williamson on their very first English club tours.

And without Mayall and the Bluesbreakers, there would have been no Cream, Steve Winwood or Led Zeppelin, and without those guys, well, you get the general idea. If you ever doubt Mayall’s power as a vocalist, just check out I’m Your Witchdoctor – it’s truly spine tingling stuff. He even gives Screamin’ Jay Hawkins a run for his money, and that’s saying something. JHai