10) Discharge – Hear Nothing See Nothing Say Nothing (1982)

As the ’70s came to an end, the landscape of UK punk rock had already changed. Different musical genres, such as post-punk, new wave and hardcore, were emerging from the now fractured scene bringing with it an influx of new bands. Meanwhile, in deepest Staffordshire, Discharge were already making some changes of their own. Former roadie, Kelvin ‘Cal’ Morris, was now fronting the band and they were growing into a far heavier beast.

Discharge’s first full-length release in 1981 set the UK hardcore wheels in motion. Why? was as angry as it was primitive but it wasn’t until its 1982 follow-up, Hear Nothing See Nothing Say Nothing that Discharge really discovered their destructive stride. The old sound of ’77 was now loaded with the kind of frantic drums and heavily distorted guitars reminiscent of Motörhead.

The 14 songs that make up Hear Nothing See Nothing Say Nothing don’t stray from their stringent writing formula. The eight snare blasts that violently signal the start of the record give way to a cacophony of crashing drums and soupy guitars. Guitarist Anthony ‘Bones’ Roberts and bassist Royston ‘Rainy’ Wainwright play their thick punishing riffs with the amp gain turned all the way up. It’s repetitive and direct, striking the listener harder with every musical phrase.

Throughout the record, Gary Maloney’s breakneck drumming is unstoppable, a breathless attack of kick and snare leaving no breaks for rest. This pattern of playing spawned a style of punk known as D-beat, an unrelenting and extremely heavy form of anarcho-punk. Many of these D-beat bands would go as far as to adopt either the prefix or suffix of Discharge’s name as a homage to the British band’s legacy – Sweden’s Disfear for example.

The short vocal bursts of singer Cal Morris, as unintelligible as they may sound, are battle cries designed to incite action. Lyrically, the five-piece depict a world amidst full-blown nuclear warfare, an unsurprising theme given the political and military tension in the early ’80s. In A Hell On Earth, Cal foretells, “A glaring light, an unnatural tremor … Men, women and children groaning in agony from the intolerable pains of their burns”. The stark, post-apocalyptic imagery that goes hand in hand with Hear Nothing See Nothing Say Nothing resonates today in the artwork and merch designs of popular punk bands like Tragedy.

This fast and visceral form of punk heralded a new age of extreme music. From the brutal grind of Napalm Death to the stadium metal of Metallica, Hear Nothing See Nothing Say Nothing acted as the rousing stimulant heavy music needed.

9) Misfits – Walk Among Us (1982)

For a brief moment in the late 80s, the Misfits were just about the coolest band on the planet. It was 1987, and Metallica had covered two of their tracks, Last Caress and Green Hell, on their Garage Days Re-revisited EP. This cult punk band from working-class New Jersey were suddenly the name on every on-trend music fan’s lips – the fact that they’d split up several years earlier was neither here nor there.

But it was in their original incarnation between 1977 and 1983 that they made history. Their very first album, Static Age – an instant classic recorded in 1978, but criminally unreleased until 1997 – was buzzsaw punk-pop drenched in fake blood. But with 1981’s peerless Walk Among Us (the second album they recorded, though the first to be released, and the first with Jerry’s brother Paul ‘Doyle’ Caiafa on guitar), the band single-handedly kickstarted that gloriously twisted micro-genre, horror-punk. Their music – a darker, bloodier take on the Ramones’ 50s-indebted bubblegum punk – and their look – be-muscled gravediggers glowering out from under ‘devil locks’ – would influence bands from Metallica and GN’R, to AFI and Slipknot, through My Chemical Romance and Black Veil Brides (but don’t hold that against them).

“I always felt that we were on to something big,” current Misfits bassist Jerry Only told Metal Hammer in 2016. “The impact was far ahead of its time. When Metallica and others like them looked at it, they saw the purity and the genius behind what it was. The songs are simple – anybody can pick up a guitar and learn one of our songs without knowing how to play – but it’s the hooks that have captured the attention of the last three generations. It was fast, hard and real, and the bottom line was we didn’t give a fuck. We weren’t doing it to be rockstars. We were anti-rockstars, and we wanted to be scorned and hated. I think we’ve done a good job!”

They didn’t know it at the time, but the Misfits would be the bridge between the US punk scene and its younger, gnarlier brother, hardcore. They muscled onto bills at CBGBs, the ground zero of New York punk; they’d take the stage at 3am to a roomful of strung-out scenesters.

“Our shows got crazy” said Only. “You’d get skinheads jumping around, beating the crap outta each other in front of the stage. We were something ya just couldn’t cage.”

8) The Stranglers – Rattus Norvegicus (1977)

The ultimate gang of punk outriders, The Stranglers never bothered to endear themselves to the mainstream public or the music press. Early gigs often saw mass walkouts and punch-ups. In 1975, two years before their debut single, Melody Maker sneered that “the only sense in which The Stranglers could be considered new wave is that no one had the gall to palm off this rubbish before”. It’s a put-down that sounds even more risible today, given a catalogue with some 23 hit singles and 17 Top 40 albums.

Forged in the unforgiving pub-rock climate of the early 70s, the band’s combative attitude aligned them to the punk scene without ever being a total part of it. This pariah status was due partly to their un-punk backgrounds. Drummer Jet Black was a former ice-cream manufacturer who was already nearing 40; keyboard player Dave Greenfield had been in a prog rock group; bassist Jean-Jacques Burnel was a classically trained guitar player; singer/guitarist Hugh Cornwell was a former biochemist and lab rat.

They formed as the Guildford Stranglers in 1974. Support slots with Patti Smith and the Ramones introduced them to a wider punk audience, while a balance of quality and productivity (their first three albums span just 13 months) brought a loyal following of their own. “More hard-core punks definitely didn’t like us,” Burnel remarked later.

Yet it was their very separateness that made them special. They refused to follow any codes but their own, and their repertoire found room for arsey post-punk, prog, jazz, avant-garde noise, sophisticated balladry and exquisite pop. The band were capable of being spiky, boorish and arrogant one minute, then smart, intellectual and humane the next.

Bridging the gap between pub-rock and new wave, The Stranglers’ debut was a brutal assault on the senses, taking on all-comers and refusing to adhere to membership of any hip London scene. Greenfield’s post-Seeds keyboards and Burnel’s bass sketch a trademark sound that was far more musically savvy than most of their peers. The sneery grunt of Hugh Cornwell only added to the band’s take-no-prisoners allure. And while it’s still difficult to forgive the blatant lyrical misogyny in songs like Peaches, some redemption comes in the shape of such magnificent missives as (Get A) Grip (On Yourself) and Hanging Around.

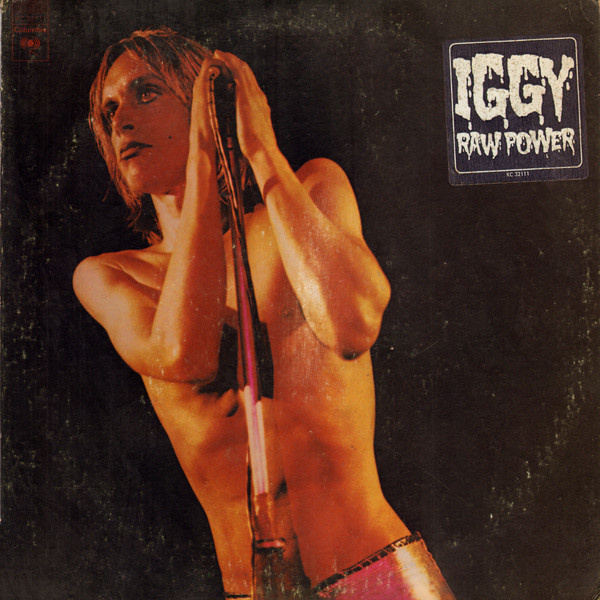

7) The Stooges – Raw Power (1973)

Iggy Pop is rock’n’roll’s most notorious outlaw. Born James Jewel Osterberg in the industrial rust pile of Detroit in 1947, wired like a Frankenstein creature, Iggy burst onto the stages of Motor City in the late 60s, spray-painted like a killer robot, a mad bag of screaming skin ’n’ bones leading the scuzziest, loudest, most violent gang of hardcore stooges the world had ever recoiled from.

Iggy virtually invented every stock punk rock move in the book, all while stumbling through a fiery narco buzz in the searing summer of 1969. The early years of The Stooges will cement his legend forever, as Iggy took rock away from the squares and turned it into a dangerous, knife-wielding satanic sex orgy filled with criminals and thugs. And it was awesome.

The bad news about Raw Power is that the tin-eared production turned the dynamics of its songs into mud. The good news is that unhinged combat-rockers like Search And Destroy, Raw Power and Your Pretty Face Is Going To Hell actually sound better buried under a wall of ear-shredding distortion.

“The sleeve drew me in right away,” The Cult guitarist Billy Duffy told TeamRock of the album in 2016. “The visuals had Iggy and his cool pants, and the guitar player with the stack of Marshalls. I was totally ready for all of that. The music hit me next. It was powerful and energetic, but it was slightly sophisticated because of James Williamson’s guitar playing. He seemed to be more evolved – or maybe involved – in his picking technique than some other guys. It excited me.”

He wasn’t the only one the album’s intricate, innovative guitar playing had an impact on. In fact, it went on to change the legacy of punk forever. “I learned to play guitar to that album,” Sex Pistols guitarist Steve Jones told Classic Rock in 2017. “That was a big one for me. James Williamson is such a beautiful guitar player, man. Really unique riffs that he had. Way different than Ron Asheton. I’m not taking nothing away from him – his riffs, his soloing, and his spirit and what he did play is really good. But James Williamson is a way technically better guitar player. He was doing a lot of stuff, but it didn’t take away the drive. It still had a big drive in it. He’s an underrated guitar player, for sure.”

This was The Stooges’ last stand, written and recorded in London under a sickly black cloud of betrayal, drugs and doom. The Raw Power album was a desperate, flailing last stab at infamy. And it worked. You simply cannot out-rock this perfectly-titled album. You can’t make it sound any better, either, as Iggy’s noisy, unnecessary 1998 remix attests to. Stick with the real thing.

6) Stiff Little Fingers – Inflammable Material (1979)

Exploding out of Belfast and breathing new life into a flagging punk scene, Stiff Little Fingers – fronted by raw-throated firebrand Jake Burns – saw their debut album Inflammable Material album reach the UK Top 20 on its release in 1979. The raw, angst-ridden sound influenced largely by the Irish Troubles, Inflammable Material veered from spiky anthems like Suspect Device and White Noise to a remarkably mature take on Bob Marley’s Johnny Was that shone a light on the vibrant quartet’s burgeoning abilities.

“Belfast was a backwater in those days, so we were always going to be playing catch-up,” Burns told Classic Rock in 2017. “When we first got into rock music we were used to bands bypassing Northern Ireland. We reckoned the only way we were ever going to hear rock music played live was to do it ourselves. [Inflammable Material] was our initial burst of anger, comparable to the initial bursts on the mainland and in New York.”

“My sister bought me Stiff Little Fingers’ first album, Inflammable Material, just after it came out in 1979 and I instantly fell in love with it,” Black Star Riders frontman Ricky Warwick told TeamRock in 2016. “I was just starting to get into punk, but I’d never heard anything like it. Coming from Northern Ireland, the fact that they were from Belfast made them even cooler to me. I just thought ‘Wow, these guys are from the same place as us and they’re singing about it and they sound amazing’.

“From the opening riff of Suspect Device I was hooked. An utterly explosive song, which took such an unflinching look at what was going on in Northern Ireland at the time. Punk rock gave kids from both sides of the community something positive to direct their anger and frustration towards, and Suspect Device is simply one of the finest punk songs ever. I’ll never forget hearing Alternative Ulster and reading those lyrics for the first time. It really should be the national anthem in Northern Ireland. What a song.”

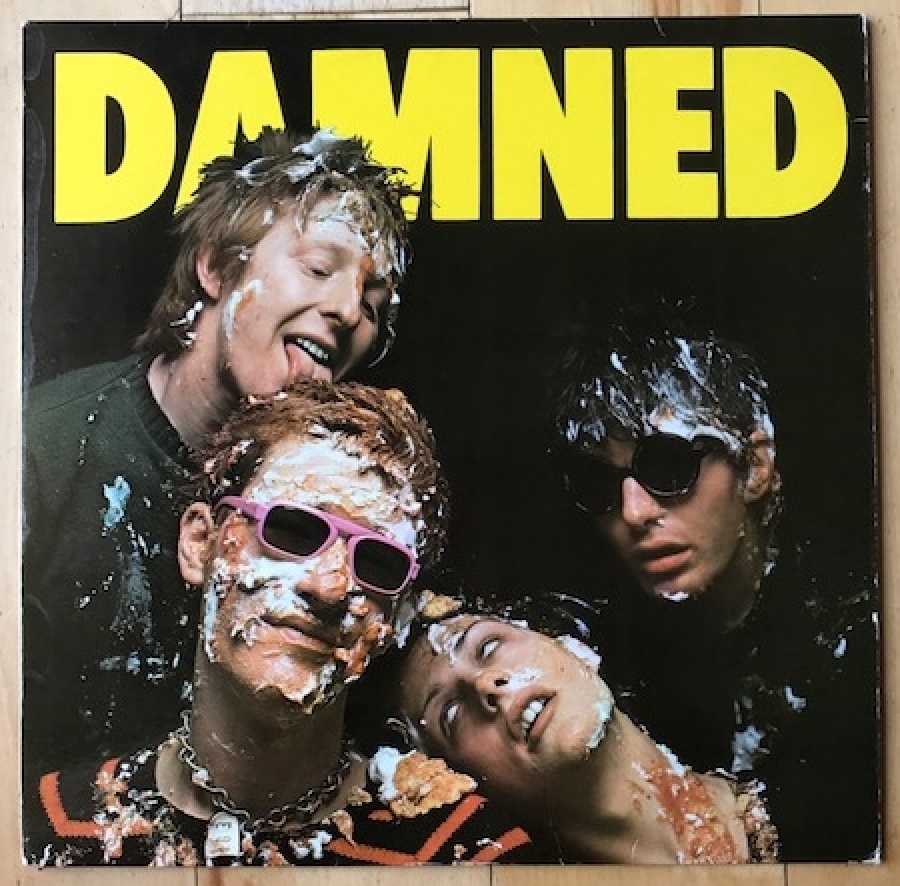

5) The Damned – Damned Damned Damned (1977)

On February 18 1977, Stiff Records released the first British punk album. The Damned’s Damned Damned Damned combined the heads-down, no-nonsense approach of The Ramones with the demented, frantic aggression of The Stooges, and screeched to a fizzing climax in just under 30 minutes. Legendary BBC Radio 1 DJ John Peel celebrated the album’s arrival by playing five tracks on his show, and shortly after the band jetted off to New York to become the first punk band to embark on a US tour.

The Damned were punk’s prime movers. The Sex Pistols and The Clash may have been more fêted by press and public alike, their reputations funded by major labels and massaged by calculating managers, but The Damned repeatedly beat them to the gate. They were the first to release a single, the first to tour the US and the first to release an album. They weren’t the most proficient of players, but God, were they effective. And nothing illustrated that more explicitly than Damned Damned Damned.

A head-spinning blast of noise, Damned Damned Damned found the band tearing through a dozen songs in just over half an hour. It was utterly devoid of any of the preening rhetoric of The Clash or the Pistols’ misanthropic bile. Instead it was a riotous explosion of fun. Speed was key, in more ways than one. “I’ve honestly smoked less spliffs than Bill Clinton,” co-founder Captain Sensible told Classic Rock in 2012, “but we used to do a bit of sniff and we had a few nosebleeds too. For a fast-paced punk set, it seemed to suit it all quite well.”

When the album’s first single, New Rose, was released, it may not have troubled the charts, but it heralded a new era – urgent, primal and unstoppable. New Rose was the first recorded acknowledgement of punk, a form of music that aimed to sweep aside everything in its path. Or at least cause a fair bit of bloody mayhem trying.

Alongside New Rose, there was the irrepressible Neat Neat Neat and sinister beauties like I Fall, Born To Kill and So Messed Up. Feel The Pain alluded to illicit bouts of S&M, while Fan Club examined the wobbly lines between band worship and manipulation.

“We didn’t have a clue what we were doing,” said drummer Rat Scabies. “Or whether it was going to be loved or even listened to. But the first playback was one of those moments you never forget. It just hit the spot and captured a moment. It was like taking off in a jet.”

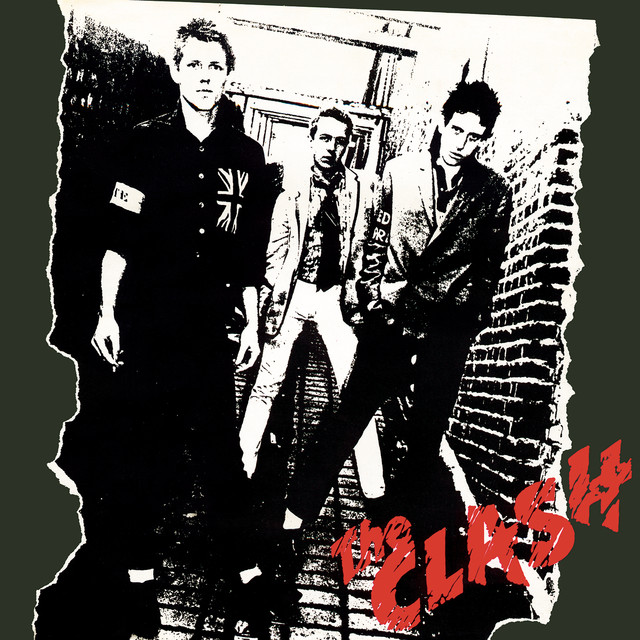

4) The Clash – The Clash (1977)

The holy trinity of punk were so perfectly formed in 1977 that it’s hard to imagine the scene without any one of them. The Pistols: searing and sneering, nihilistic and iconic (the artwork, the clothes). The Damned: the court jesters. Daft, tough, Tiswas-anarchic, a British Stooges/MC5. And The Clash: the guttersnipes and street punks, the voice you could relate to, and without whom it’s hard to imagine The Jam, Stiff Little Fingers, Sham 69 or Generation X, let alone Green Day, Rancid, or maybe even U2.

The Clash articulated the frustrations of working class kids in a way that the chin-stroking protest pop of previous generations couldn’t hope to, in a way that was more inclusive than the fury of the Pistols or the Damned’s goth theatre. (And, yeah genius, we know the irony: Joe Strummer went to a private boarding school and his father was a top diplomat. Hate to break it to you but David Bowie wasn’t really a spaceman, Tom Waits wasn’t a hobo and Ice-T didn’t really kill cops.)

The Clash was hurriedly-written and recorded and it’s a messy and thrilling snapshot of two creative forces gelling for the first time. From their vocals (Strummer’s yobbish bark balanced by Jones’s boyish sensitivity) to their lyrics (famously, Strummer changed Jones’s track I’m So Bored With You to I’m So Bored With The USA), and even their guitar-playing (Joe’s choppy rhythm guitar versus Mick’s slightly weedy-but-melodic lead), the album is a true Strummer/Jones production. Both men were classic rock’n’roll dreamers. To find themselves in the right time and right place with the perfect partners must have been a buzz and, amid the anger and the outrage, the album captures that rock’n’roll woah perfectly.

Slap-bang in the middle of each side are two tracks about race that would define the band’s career: White Riot and Police And Thieves. Junior Murvin’s Police And Thieves single was released in the UK in July 1976, the perfect soundtrack to that year’s Notting Hill carnival riot and tailor-made for the Roxy, the punk club where Don Letts DJ’d, playing reggae and dub records (there just weren’t enough punk records to play all night and reggae’s outsider status meant it fitted perfectly). The Clash gave the song steel toe-capped boots and a knuckleduster to create punk-reggae, cementing a relationship between the two genres that continues to this day.

If Police And Thieves embraced multi-racial Britain, both musically and philosophically, White Riot was a little more singular. A two-chord rallying cry – rock music with all the blues stripped out of it (the album version is twice as fast and three times more furious than the laughably rinky-dink 7” version that came out just a month before in March 1977) – White Riot suggests that white people could learn a lot from west London’s black community, that if they too stood up against authority they could take over, instead of taking orders: ‘All the power in the hands/Of the people rich enough to buy it/While we walk the streets/Too chicken to even try it’.

Strummer’s lyric clearly admires the section of the black community that ‘don’t mind throwing a brick’ – the rioters pushed into confrontations by aggressive policing and refusing to take it anymore. Where White Riot becomes problematic is in the fact that its sentiments echo that of many far right groups. The National Front had similar views: that Britain was run by bankers (read ‘jews’) and white people should fight back and reclaim their country. Punk rock was a musical white riot – mostly white bands singing music (mostly) stripped of black influence – and a far-right and fuckwitted element of the Oi! movement made much mileage out of this.

If The Clash never really disavowed White Riot, they also never recorded anything like it again. It split the audience and ultimately split the band too.

3) Dead Kennedys – Fresh Fruit For Rotting Vegetables (1980)

Formed in San Francisco in 1978, Dead Kennedys were a driving force in the West Coast’s punk scene. The quartet’s sound took influences from instrumental surf rock, rockabilly and garage rock and wrapped it up in super-charged punk. With tongue firmly in cheek, frontman Jello Biafra’s politically-charged lyrics provided a scathing commentary on the social issues of the day.

“Born of a time when much of UK punk’s first wave had grown flabby,” wrote Alex Deller for the BBC in 2011, “the Dead Kennedys stood alongside fellow upstarts MDC, Bad Brains and the Misfits in forging their own harder, wilder sounds and bringing the genre to its next logical stage of development. Fusing bright, slashing chords and hyperactive bass runs with frontman Jello Biafra’s acerbic yodel-cum-snarl the band mercilessly dispatched cruel, irreverent and unceremonious potshots at political corruption and large-scale human idiocy with a mixture of crackling ire and bleak, yellow-fanged comedy.”

That sense of quick-witted, never-miss-a-beat humour which consistently refused to take any prisoners is what made Fresh Fruit… stand apart from all its contemporaries. “Fresh Fruit… is the ultimate hardcore comedy album,” wrote Rolling Stone in 2016, “with singer Jello Biafra playing Johnny Rotten as goofball satirist on songs like California Über Alles and Holiday In Cambodia. Fuelled by the band’s technically sharp guitarist, East Bay Ray Pepperell, Fresh Fruit also had more musical fire than contemporary efforts by similarly over-the-top hardcore shock-rockers like Fear or the Adolescents.”

“To me, California Über Alles is one of our best songs,” East Bay Ray told TeamRock in 2015. “It’s got so much going for it. It may not sound that complicated on the surface but it actually has a lot more sections than most other songs. And a secret, unexpected ingredient with the drum beat. I never get tired of playing it.”

“California Über Alles is the perfect political punk rock song,” Anti-Flag bassist Chris #2 agreed in 2016. “Dead Kennedys as players and musicians were untouchable. Jazz-trained drumming and bass playing that was not heard in punk music. Jello [Biafra, vocals] did not believe in grey. Each song was about an education process. And that’s why they were my favourite band.”

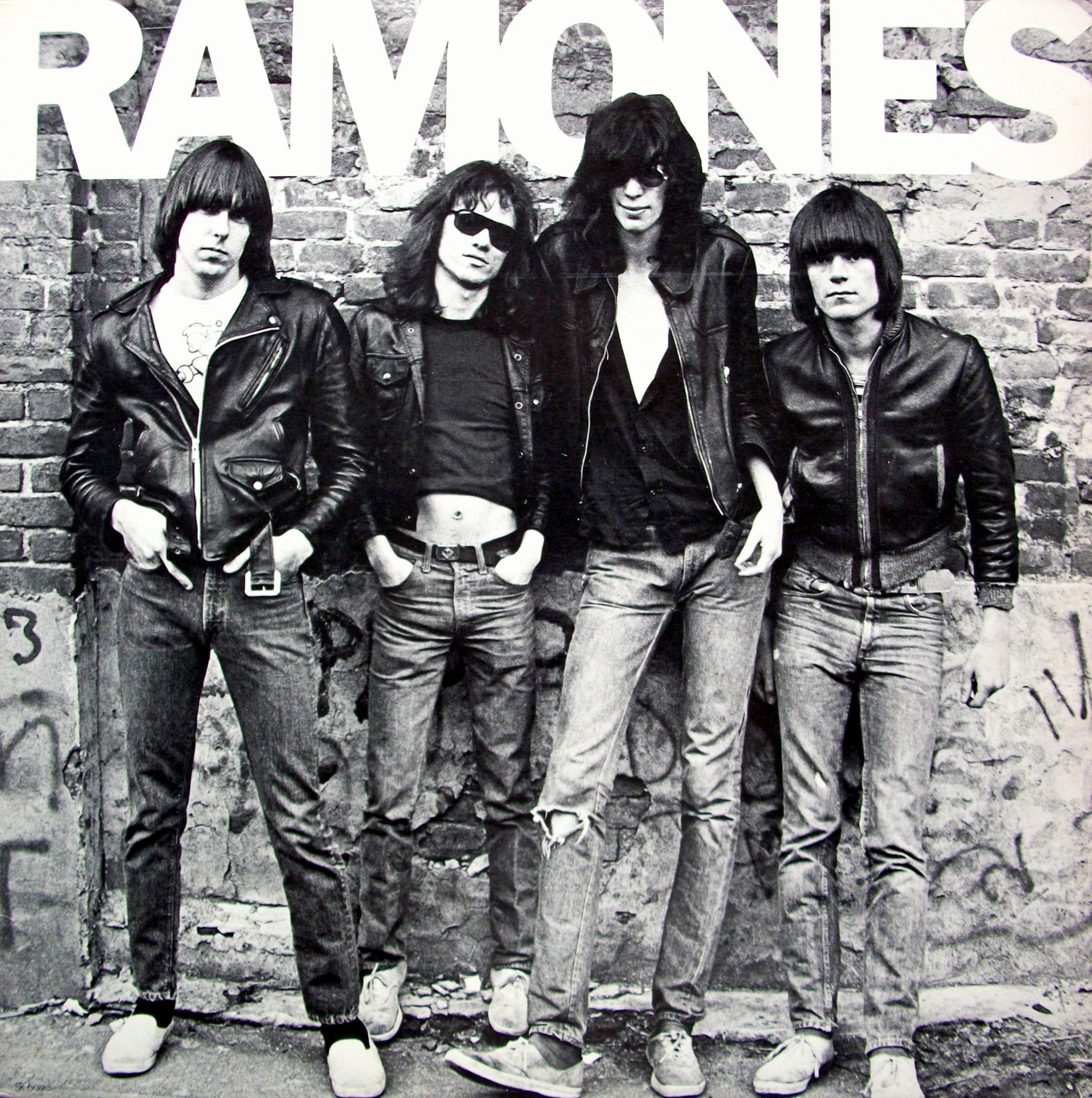

2) Ramones – Ramones (1976)

Frayed and ragged like well-worn sneakers, the bubblegum blitz of New York’s Ramones was as simple and blunt as a mallet. Born in 1974 at New York’s legendary CBGB dive, the musically unschooled and outwardly unwashed Ramones unwittingly scribbled the book of 1-2-3-4, do-it-yourself punk rock. Along the way they became slouched heroes to future generations of speed freaks, grunge geeks and pawn-shop guitar slashers with neither the dexterity nor the inclination to mimic Zeppelin or Clapton.

From Roberta Bayley’s grainy black-and-white cover photo to the four days recording time it took, the Ramones’ shoestring-budget ($6,400) self-titled debut album was born in a blur and delivered 14 songs in less than 29 minutes. Introduced to a world that at the time was spaced out on the likes of Moody Blues and Styx, the Ramones bashed out such dizzying ditties as Now I Wanna Sniff Some Glue, Beat On The Brat, Blitzkrieg Bop and the hustler anthem 53rd & 3rd.

Arguably the album – and band’s – defining track, Blitzkrieg Bop was just over two minutes of pure adrenalin, a three-chord ruck that hurtled by with furious abandon. It was the song that helped launch the Ramones as the roaring embodiment of New York punk. Less than two months later The Clash, the Sex Pistols and The Damned were all in attendance at the band’s historic first UK gig at the Roundhouse, which the NME claimed they “reduced to the hottest, sleaziest garage ever”. Blitzkrieg Bop was likened to a rallying call by Buzzcocks chief Pete Shelley.

“I was at college when an advance copy of Ramones came into one of the local record stores,” Butch Vig told TeamRock in 2016. “I remember being in there when the guy put it on, and just being floored by how amazing it sounded. So I went back a week later and was first in line when it went on sale. It really was a startling sound for that time. There were all these bands like Emerson Lake and Palmer that would do these extended muso solos. The Ramones were the exact opposite of that, they were so stripped-down and bare-boned and so fast. It was a breath of fresh air, an adrenaline shot.”

“We were so unique,” Tommy Ramone told Classic Rock shortly before his death in 2014. “It’s hard to imagine now, but what we were doing was so different from anything anybody had heard before. It was like we were from another world.”

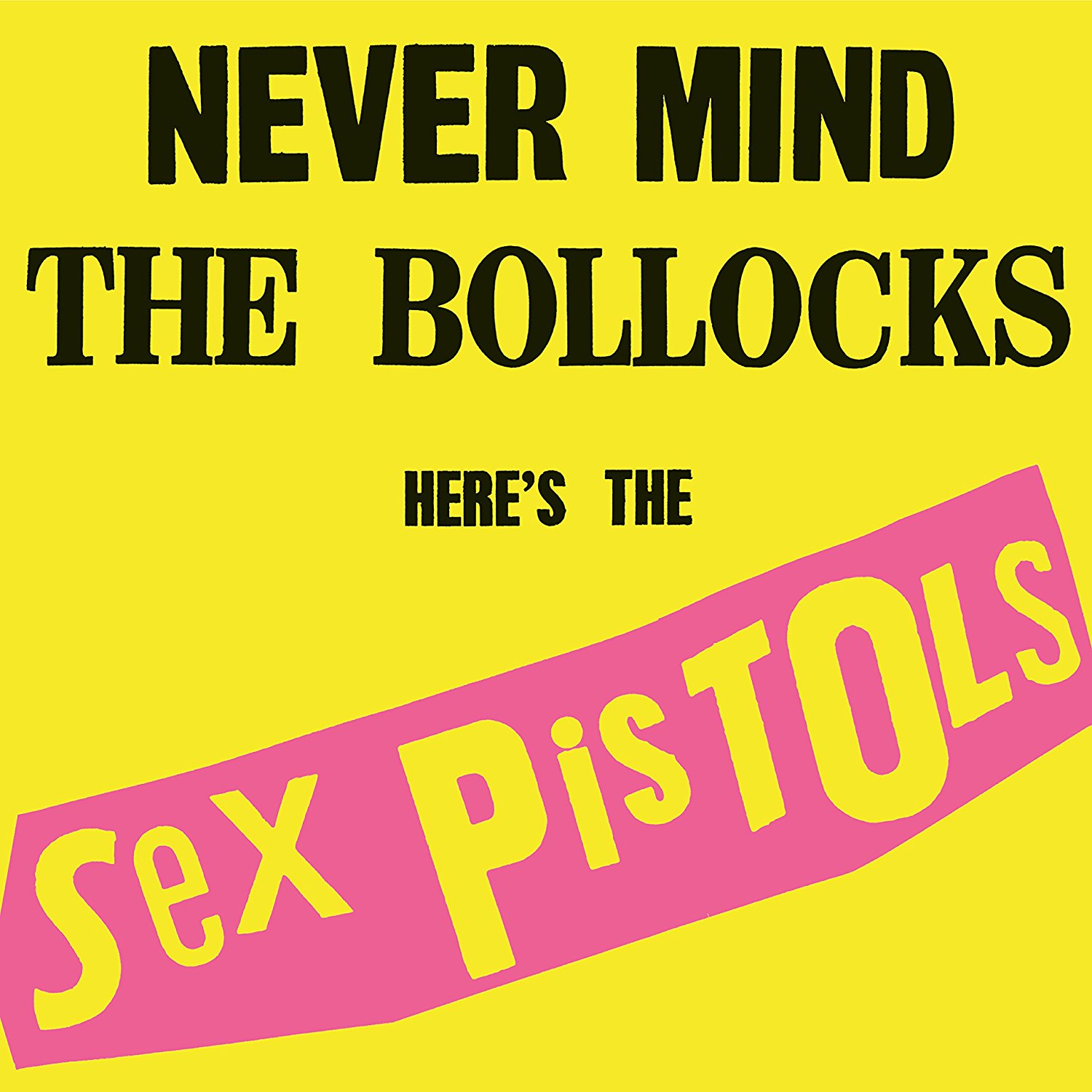

1) Sex Pistols – Never Mind The Bollocks, Here’s The Sex Pistols (1977)

Even 40 years later, this is a divisive album. The bottom half of the internet will light up at the merest suggestion of its name. There are still plenty who believe that the Sex Pistols were a mere construct, a prototype Take That fashioned simply to sell unfortunate trousers, and that their solitary album of original material was, well, just an album; unsophisticated, iconoclastic, raw, but a bit of a paper tiger.

This is, however, an opinion that disregards all available evidence, because what we have here is not only the best punk album ever made, but it’s also one of the most powerful, enduringly influential and complete recorded statements crafted in any genre. Disagree? Go tell it to your religious fundamentalist flat-earth brethren, because you’re wrong.

“The Sex Pistols just fucking scared me,” Fugazi and Minor Threat frontman Ian MacKaye told TeamRock in 2014. “In November 1978 I borrowed Never Mind The Bollocks from some friends and I was just freaked out by it. There was something about that record that was creepy. I mean Bodies, especially, that’s a great riff and a great song but the lyrical thing was mind-blowing. I mean, people tend to think of the Sex Pistols now as kind of a cute cartoon band, but that record is unbelievable. And then I started to hear it, and I started to understand it, and I was blown away and I started wanting to hear more.”

In NMTB producer Chris Thomas, the Pistols found their Visconti. Their savant genius was already there – all they needed was an interpreter to translate passion into the language of vinyl, and here it was. A titanic wall of guitars, The Stooges Spectorised, the Dolls Anglicised and John Lydon distilling a lost, dismissed and disenfranchised generation’s directionless, nihilistic fury into succinct spitballs of vented spleen as intense, uncompromising and affecting as any dead poetry.

There can’t have been many more hair-raising couplets in rock’s history than Anarchy In The UK’s ‘I am an anti-christ! I am an anar-kyste!’, and its impact has hardly been dulled with time or repeated listens. Then, to publicly dismiss our reigning monarch with God Save The Queen – the album’s crown jewel, if you will – by observing ‘she ain’t no human being’ in the year of her universally celebrated Silver Jubilee, represented a whole new level of provocation to the establishment. In terms of timing alone, that song was a work of spittle-flecked, petulant genius.

“When we recorded that, I knew we had something special because it had all the elements for a great rock tune,” Steve Jones told Total Guitar Magazine in 2013. “There was a backlash from the royalists. They thought we were taking the piss out of the Queen. I can see how that was a problem for some people back then. It got heavy sometimes. Lyrically, it’s genius, telling the Queen what she’s done to you. It wasn’t just a rock band: it got political and it was offensive to a lot of people. It’s a perfect three-and-a-bit-minute pop song.”

Check out a selection of choice tunes from each album below. Apart from Crass, who are too punk for Spotify.

Green Day's 10 most punk moments

The shape of punk to come: How punk became part of classic rock's story