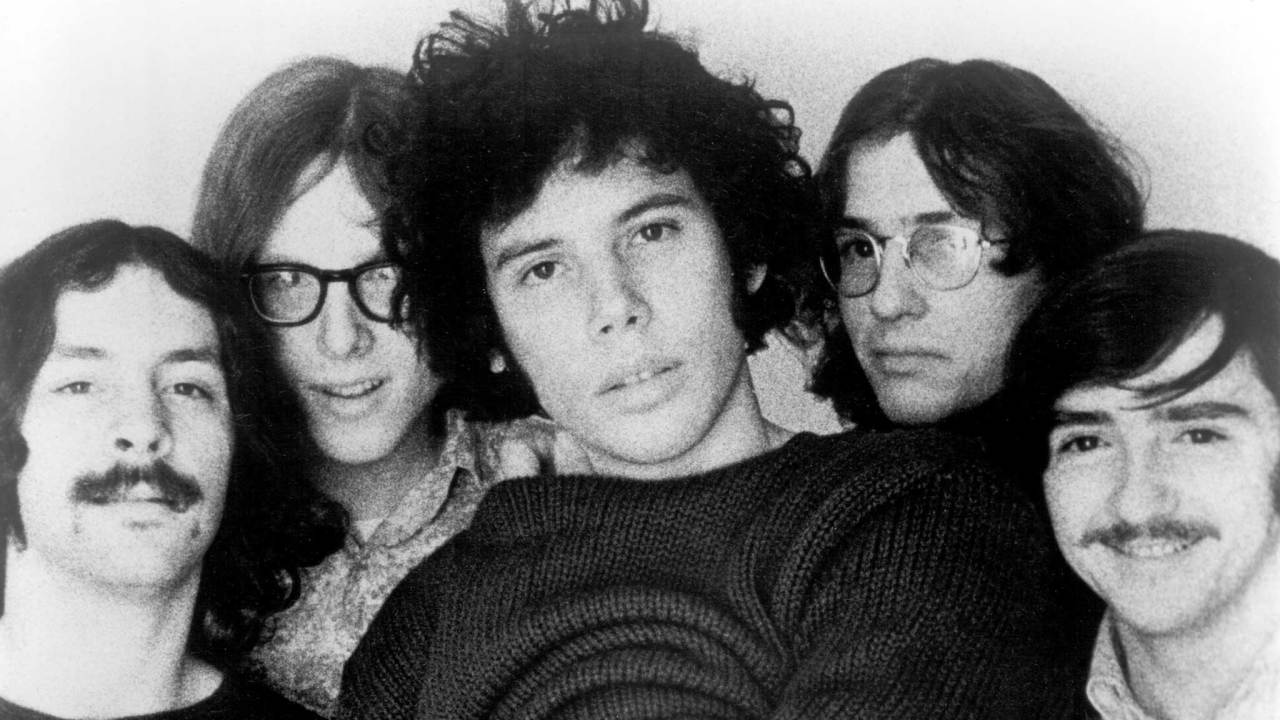

Autumn 1967. Lake Avenue, St. James. Suffolk County, New York State. In a house in the woods, a bunch of young men are living together in ramshackle bohemian splendour – 20-year-old students, graduates and wannabe musicians with a phobia for the 9-5, their days are spent in endless jamming and dope smoking. No one has money for utilities so the house is large, cold and damp. The windows are covered in blankets, the walls are painted black. In the living room, someone has painted a mural of Jim Morrison depicted as a strutting lion.

Residents include Donald Roeser, wizard guitarist and part-time student at Stony Brook University and Allen Lanier, a keyboard player and guitarist in the process of extricating himself from the draft. Patently ill-equipped to fight the war in Vietnam, Allen is working as an apprentice editor on industrial films. When he goes AWOL, Jeff Latham takes over.

On bass is Andrew Winters, a mordant, wise-cracking New Yorker who should take credit for starting the band. Winters works as delivery boy at a drug-store in nearby Smithtown run by the father of one Samuel ‘Sandy’ Pearlman, an erudite scribbler for the ground-breaking Crawdaddy magazine who - legend has it - first uses the term ‘Heavy Metal’ in a review of The Notorious Byrd Brothers. Later on, Sandy will become the emerging group’s lyricist, mentor, conceptualist, producer and manager. His friend, another Stony Brook student and fellow Crawdaddy, scribe Richard Meltzer, writes arcane verses that will be turned into songs.

The drummer drums is Albert Bouchard, a drop-out civil engineer and friend of Don’s from Clarkson College, Potsdam, NY. Albert is also an occasional contributor to Crawdaddy, writing about Buffalo Springfield. And completing this ramshackle ensemble is guitarist/bassist John Wiesenthal, who once had tuition from Pete Seeger and taught Jackson Browne some folk chords, and tall handsome tenor sax player and singer Jeff Richards.

In October 1967, Pearlman gets the boys their debut gig as Steve Noonan’s backing band at the Stony Brook University gymnasium, and since they need a name for this event, and Meltzer’s suggestion of Cow hasn’t been popular, Sandy christens them Soft White Underbelly: “after Winston Churchill’s description of Italy as the soft underbelly of the axis” he explains. Pearlman’s obsession with WW2 military history will crop up later when he writes the Blue Oyster Cult song ME 262.

Soft White Underbelly play a blues set in November at the Café au Go-Go supporting James Cotton, and do their own thing at a Christmas party in Stony Brook to try out some original material: Bouchard and Meltzer’s All-Night Gas Station, a lengthy psych jam, will mutate into A Fact About Sneakers - a song they record as Stalk-Forrest Group in 1970. Albert’s other contribution is You. “That was a dream I had about being drafted, though I never was,” he says. “Sandy changed the words to an elaborate tale about Canadian Mounties. That became I’m On The Lamb, But I Ain’t No Sheep (which appears on the initially unreleased Stalk-Forrest Group album, and the debut BOC album), and then as The Red and the Black (on Tyranny and Mutation). For the first half dozen shows I sang and played drums using a boom microphone. Jeff Richards was a very good singer but he had terrible stage fright. It wasn’t ideal. We needed a singer. Before me they’d tried out David Roter and Jeff Kagel.” Meltzer tried his hand too, but usually confined himself to shouting obscenities.

”Meltzer was always contrary”, says Donald. “He had no boundaries. He was like a shark: keep on moving or you drown. I liked him a lot but he had no discretion. Civil society wouldn’t function if everyone were like him. But he and Sandy did have folders full of possibly great lyrics, and we spent hours sorting them out.”

In early ’68 a longhaired stranger arrived at the house in the woods and found “what looked like elves, playing among the trees.” This was Les Braunstein, who entered the Underbelly after bumping into Pearlman’s girlfriend (later wife) Joan Shapiro while visiting friends on campus. An aspiring songwriter, and a graduate from nearby Hobart, where he’d shared anti-authoritarian conversations with fellow student Eric Bloom, Les had written a cutesy jug band track called _I’m in Love With a Big Blue Frog_ that Peter, Paul and Mary covered as their obligatory kiddy song on Album 1700 (1967). It was more than faintly twee, yet this ditty gave Les a regular $75 a month royalty cheque, enabling him to buy a VW bus. He had other things to commend him: he’d seen The Doors play in 1967 and he’d hung out with Nico and Tim Hardin.

Smoking a joint with Joan on his bus, Braunstein played her a few songs. “She said: ‘you must meet the boys, Soft White Underbelly. My boyfriend is guiding them.’ When I turned up at St. James they were taking a break and smoking up so I joined in. We got more stoned on the bus and then I entered their rehearsal room, with all the equipment squeezed in. They played and it sounded like nothing I’d ever heard before: powerful, good and electric. I got very paranoid. I felt so trapped inside the music I had to run outside. Joan came to fetch me and said ‘oh, that happens to everybody.’ I went back and it was still the best thing ever – Donald, Albert, Allen and Andrew. They showed me some songs. Meltzer’s were whacked out; so odd I didn’t see how they could ever make sense, but Donald and Albert worked that out.”

Braunstein joined the “hangers-out”. Once integrated, he offered to participate and sang: “I’m in the band house, we’re all in the band house”. Sheer poetry. “Yeah, but it got more complicated. I tried out one of my college jug band songs, Rational Passional; slightly silly but it came out like the Jefferson Airplane. The lyrics were pretty good. ‘I was at selective service [a US agency that maintains data on people potentially subject to military conscription] and the people made me nervous, so I asked the sergeant why they made me come. He said do just what you’re ordered, or we’ll have you drawn and quartered. You’re a lousy commie peace creep hippy bum…’”

Brausntein joined in earnest after jumping on stage at the Anderson Yiddish Theatre, Greenwich Village but doesn’t complete a set until February, a drugs bust benefit starring Country Joe & The Fish and The Fugs. Back from the army on a furlough, Lanier was horrified to find “the band house guy” upfront. “The constant, the communal context was altered,” he remembers. “I was always an outsider as a matter of style but we were great mates, also we weren’t. It was all about the band.”

Ever the open book, Les understands Al’s antipathy. “Allen Lanier did not come alone, he came with the Gothic South and the French poets. The boy was haunted. We didn’t talk much. He attacked the keyboards with an intensity that was missing in his everyday demeanor, where he was quiet, courteous and distant. We were completely non-confrontational as people. With the occasional exception of Andrew, nobody gave anyone else a hard time. Everyone expressed themselves about the music as it came together; that was understood as being constructive. But what was not expressed in words was never hidden in attitude. I could see it most clearly in Allen. He was frustrated at seeing the change in the band’s persona that I caused. ‘Why do we want a singer with vibrato?’ he asked. He had been playing and jamming with the band for months, had started to dream the big dreams, had been dragged away into the army and now, comes back to find that this guy who had been singing a little in the band house was now the singer with the band. Plus life, which was obviously suffering and distress, was what to this guy? I was too happy for him. I liked Allen, but there was no place for me in his dream.”

Better gigs arrived. In April ’68 SWU supported BB King and Chuck Berry at the Generation Club, NYC, and also backed the rock and roll star.

Albert: “That was very cool. We arrived early. Chuck didn’t turn up ‘til 15 minutes before the doors opened. He plugged in and asked ‘who is the drummer?’ I was actually sitting at my drums! ‘OK. You know my songs. This is what happens: when I bring the head stock of my guitar down that means stop and the song ends, but keep the beat going in your head and be ready to come back in; when I lift up my left leg and bring it down to my right leg that means wrap it up ‘cos that’s the end of the song OK?’

“He told Andrew to play Memphis ‘but not like the record, like Johnny Rivers’ and Andy goes ‘wh-a-aat?’ That was the entire sound check. We played, then we backed him and he was incredibly loud but lucid and dynamic. What a great singer.”

In May SWU supported the Grateful Dead at Stony Brook. Albert thought “they (the Dead) were a little boring, went on and on and the vocals didn’t do anything. But Don liked Jerry Garcia and stole a bunch of ideas. They were a folky jug band and we still had an East Coast jazzy influence. Oh, but Phil Lesh came over and said ‘you’ll be great some day’. Dunno if that was a compliment.”

Finally, a break. Pearlman persuaded Elektra boss Jac Holzman to watch the Underbelly play in the Ballroom at the Hotel Diplomat, New York City, where Meltzer gave the record company boss a joint laced with horse tranquilliser. Evidently it worked because after they climaxed with All Night Gas Station Jac came flying out of the bleachers. “He jumped on stage threw his arms round me and hugged me and said ‘You’re in the family boy!’ It was a very special moment,” says Les.

Whether he liked SWU is a moot point, but Holzman viewed Les as an East Coast Jim Morrison. “Probably because at the end of the set I made up this story about going outside the Diplomat with a flower child space girl and then this dude arrives and she doesn’t like him so she pulls out these two long steel pins and I start screaming and she plunges them into her eyes.

In late ’68 SWU started recording at Elektra’s New York studio, then moved to the recently opened A&R Studio 2 in early 1969. Here they recorded enough material for an album. The songs included Mothra (Pearlman and Lanier), an early Cult-styled abstract Japanese horror monster piece, Queen’s Boulevard (Pearlman and Lanier), about the death of the classic American motorcycle, the Fleischmann’s area of New York and the joys of driving down said Boulevard, and Fantasy Morass (Meltzer and Lanier) about urinating in a public toilet with a lyric that goes “It’s not a yellow cloud, it’s not a smelly vent…”

Bark in the Sun (Meltzer and Bouchard) would become the Secret Treaties song, Cagey Cretins, when recycled with another SWU tune, Mystic Stump, something they never recorded. The original contains another fine Meltzer couplet: ‘You vomit slime, my armpits rhyme like artichoke hearts, not our own hearts.’

Pearlman and Albert wrote Buddha’s Knee, a trance song performed under the influence of LSD with a fast guitar passage that indicated how ridiculously good Donald had become on guitar.

There were also attempts at the following: St. Cecelia, Bonomo’s Turkish Taffy, Arthur Comics, Ragamuffin Dumpling (written by Meltzer about Les who used to make the band dumplings and also referred to himself as ‘the magic man’ of the song), Donovan’s Monkey and All Night Gas Station. These six were revisited and drastically altered by the Stalk-Forrest Group. Finally, there was a Braunstein folk song called Jay Jay that Albert says “was how Les wanted us to be. We thought ‘oh well, the Beatles always do some weird shit folk, so why not? We gave it our best shot, Allen especially.”

During the final recordings, with bemused producer Peter Siegel going slowly nuts, Les decided he didn’t like his vocals and erased them. According to Albert “He really did not want to sing Meltzer’s songs. He knew Meltzer didn’t like him and he didn’t like Richard’s tone because it wasn’t positive and was deliberately oblique. What it boiled down to was that Les wasn’t as serious about the music as the rest of us. He was gifted and talented but when he re-did his vocals it all got fucked up. He started by lying down on the floor twelve feet from the mic or he’d insist on singing when we weren’t there.” The ultimatum was sotto voce. Either Les played ball, or he could do one.

Les also wanted to draft in arranger David Horowitz and add Love/Forever Changes style strings and horns. The rest of the Underbelly were aghast but Les sees it differently. “It’s true that I had played trumpet and French Horn in college, so on Buddha’s Knee I hit a fire hose against the mic to make a metallic clang, then I blew down the brass nozzle and found this great one-note waaaah and then I blacked out. Semi-conscious, I felt more involved in the Underbelly then I ever had done. I tried it first when we played with Blood, Sweat and Tears. I hadn’t taken acid at that point.”

By mid-69 Jac Holzman was getting cold feet about his $5000 investment (far from the often reported $100.000 advance), but still called the Underbelly in for a meeting with William S. Harvey, the Elektra sleeve designer. Neither man seemed particularly pleased with the recordings, which were quirky and still unfinished. Though no official rejection was offered, bass player Andrew Winters was the most vocal dissident, since the others were non-confrontational. When Harvey, attempting to be avuncular, mentioned that ‘your album art work doesn’t have to be like typical Elektra art work’ Winters shot back “Well, that’s a good thing.”

In early summer Les was “disengaged”. He played his last show with SWU when they supported The Band at Stony Brook, back in the gym, and it felt like déjà vu. Sandy Pearlman killed the SWU sessions off, terminating them at the neck because he didn’t think them releasable. “If we’d persevered, it would have been a disaster” he said. Les went off traveling with his girlfriend Kippy and the others soon enlisted their new van man and sound guy to take his place.

His name was Eric Bloom. A new chapter was about to begin.