This article first appeared in The Blues #8, August 2013.

Earlier this year, Chicago-based Alligator Records released Cotton Mouth Man, a new album by legendary Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters sideman, James Cotton. In typical Alligator style, no opportunity was missed to get ‘Mr Superharp’s’ album into the right hands. The label got completely behind the release, as it does with every record it produces.

Even if Mr Cotton had been a complete unknown, the fact that his album carried the Alligator Records logo would have been enough to grab our attention anyway. It’s a stamp of quality at a time when blues records are churned out at an incredible rate and then left to fend for themselves.

So, you’re preaching to the choir when it comes to Alligator Records round these parts. Not only is it home to some of our favourite artists – Hound Dog Taylor, Albert Collins and, more recently, JJ Grey & Mofro and Anders Osborne – but few other labels have done more to keep the blues alive and thriving over the past 40 years. You can sign us up for the fan club and a T-shirt.

Despite our positive vibes, Alligator founder Bruce Iglauer was nervous about doing this interview. While he’s justly proud of his label’s contribution to Chicago blues history, he’s in no mood to have his creation portrayed as some noble museum piece. He said that. Not in so many words, but we got the message. That’s fair enough. For 42 years, Bruce has put his arm round the shoulders of blues legends and fresh-faced hopefuls alike, steering them towards the right audience and making sure their message is heard. The label owner’s message is that blues cannot survive by beautifully repackaged back catalogue alone. The blues needs a steady supply of fresh blood.

In fact, as we were talking with Bruce, he mentioned that he was nurturing a young artist from Mississippi who may go on to record as an Alligator artist. So, what does it take to get your name added to that distinguished roster?

“Ultimately it’s my gut that tells me whom to sign,” says Iglauer. “I listen for someone with deep blues feeling, emotional honesty, good storytelling, and the kind of catharsis and intensity that I love. I’m not worried about whether their music has traditional blues structures or lyrics. It’s how the music feels and how I respond emotionally.

“Also, I look for artists who can communicate to a live audience,” Iglauer continues. “Blues music is created by the interaction between artist and audience. If the blues is going to have that ‘healing feeling’, the artist must be able to reach into his or her deepest emotions and deliver them to the audience. It’s soul-to-soul communication.”

It was the need for ‘soul-to-soul communication’ that first brought Iglauer to Chicago by bus in the late 60s and into the gravitational pull of the man who would ultimately inspire him to form his own record label: Theodore Roosevelt ‘Hound Dog’ Taylor.

“I had one piece of information that I remembered from a folk music magazine I had picked up years before,” recalls Iglauer. “‘If you want to hear some real Chicago blues, go to the Jazz Record Mart at 7 W. Grand Ave., and Bob Koester, the owner and also the founder of Delmark Records, will take you out to the black neighbourhoods to hear the real thing.’

“I showed up at 7 W. Grand to discover a seedy little record store with an amazing jazz and blues selection. Bob Koester, the very outgoing and talkative owner, introduced me to John Fishel, a long-haired college student roughly my age, who was working behind the counter. Later that year, John and his friends organised the first Ann Arbor Blues Festival, which was the first national blues festival ever.

“It was John who took me out that night to Eddie Shaw’s little blues bar on the West Side of the city. We went on the bus through very poor and often burnt-out streets (from the riots after Martin Luther King was killed) to a storefront bar where we were the only white patrons. It was filled with musicians because it was Blue Monday, the day that everyone jammed and tried to ‘cut heads’ musically. Otis Rush was there, as was Jimmy ‘Fast Fingers’ Dawkins. Eddie, the West Side’s favourite tenor sax man, was tending bar, and the house band was led by a drummer named Little Addison and a guitar player named Boston Blackie, both stalwarts of the West Side scene.

“Also hanging out was a tall, gangly man with an almost dog-like face, big teeth and a loud, cackling laugh. He was clearly everyone’s friend, and someone told me his name was Hound Dog Taylor.”

Long story short, Hound Dog’s stint onstage that night was not a triumph. As Bruce recalls: “I dismissed him as a friendly, outgoing and hard-drinking guy whom the others let sit in because he was the life of the party… but not a good musician. Boy, was I wrong.”

Iglauer moved to Chicago at the beginning of January 1970 to take up the position of shipping clerk at Delmark Records. Soon after he found himself at Florence’s Lounge at 54th Place and Shields to catch a Sunday afternoon Hound Dog set, backed by Brewer Phillips on second guitar and Ted Harvey on drums. There was no bass player.

“It was magical!” says Iglauer. “The music was wild and full of energy, raw and raucous. Hound Dog played slide with the fifth of the six fingers on his left hand, playing a cheap Kingston Japanese guitar that distorted like crazy, while Phillips (everyone called him Phillip) played fast and ever-changing bass parts on his Fender Telecaster.

“The guitar sounds were filthy, in a good way, and Hound Dog sang in a high, true blues voice, through a cheap microphone plugged into his Silvertone amplifier. I had never seen anyone have so much fun making music, and I had never had so much fun listening to it. I knew it had to be recorded.”

It’s now the stuff of legend that Bruce tried to persuade Bob Koester to sign Hound Dog to Delmark. No dice.

“He had never heard Hound Dog with his own band and thought, as I had, that Hound Dog was more of a clown than a musician. Finally, I began to dream of recording him myself. At that time, Hound Dog had only recorded two 45s, both for small, local labels, as well as an unreleased session for a Chess slide guitar anthology. His 45s were still on the jukeboxes in some of the clubs where he played.

“When I asked him about cutting an album one night, he said the same thing he said when a fan made a request: “I’m with you, baby, I’m with you.”

When I raised the subject of money, he was clearly surprised. I doubt he’d been paid to record his 45s, and I think he was prepared to cut an album free, hoping it would lead to some gigs. I offered him $480 up front, and $240 each for Phillip and Ted, with royalties later if we sold enough. This was in line with the Musicians’ Union scale at the time.

“Of course, down the road Hound Dog made a whole lot of money from that album, as did his heirs after he died. He was happy to record, and I don’t think that he had a moment of concern about recording for Bruce, his hippie fan. No one else was asking him to record, so he had nothing to lose. Also, he knew that there was a growing white audience for the blues, and I’m sure he was thinking that this might be his doorway to it. Little did he know…”

Released in 1971, Hound Dog Taylor & The HouseRockers eponymous debut album is a landmark in electric blues. It established Alligator Records and created a blueprint for future bass-less blues groups like The White Stripes and The Black Keys.

If the album had been Bruce’s only success as a label owner, he would still be considered one of the guardian angels of Chicago blues. In truth, though, he continued cutting classics like it was no effort at all.

“My second signing was one of the all-time great blues harmonica players, Big Walter Horton. He had recorded since the early 1950s, but mostly as a sideman. I had loved his music for years and in early 1970 I was thrilled by seeing him sit in with Hound Dog Taylor, playing harp duets with his protégé and my friend Carey Bell, who was a Delmark artist. So I asked Carey to help me make a record with Walter, who was notoriously shy.

“We cut an album called simply Big Walter Horton With Carey Bell that turned out to be one of the best harp albums to come out of Chicago. Over the years it’s achieved classic status. I followed Walter’s record with the debut of a completely unknown young blues guitar player named Son Seals. After Son, I recorded Fenton Robinson, one of the classiest, subtlest bluesmen ever, and then signed another major talent, Koko Taylor, who had earned great success with her hit single of Wang Dang Doodle on Chess in the 1960s, but was back to working a day job when I signed her in 1974.”

- Albert Collins Buyer's Guide

- BB King: the life of riley

- Stevie Ray Vaughan: I Was Recording Without Drugs And Nervous As Hell

- The Blue Horizon Story

Iglauer would also sign one of the greatest blues guitarists that ever lived.

“When I started Alligator, I never dreamed of recording anyone as popular or famous as Albert Collins, ‘The Master Of The Telecaster.’

“When I was just learning about blues, Albert’s name was one of the first I heard, along with those of the three Kings. I remember seeing a big ad for his Blue Thumb album (which turned out to be a reissue of older sides) in Rolling Stone. He looked like a badass! When I moved to Chicago in 1970, I found a used copy of The Cool Sounds Of Albert Collins, which was the original album that Blue Thumb had reissued, for $1.77 – wow! It was a collection of his early 45s from his Houston days. I was fascinated with his unusual, ‘cool’ stinging guitar sound; I knew there was something different about it, but I didn’t know that it was partly because of his special open minor-chord tuning.

“The other signature factor was, of course, the large amount of reverb that he loved so much, and which was probably the inspiration for the titles of his ‘cool’ instrumentals like Frosty, Sno-Cone and Don’t Lose Your Cool. Later I heard the albums he cut for Imperial in the late 60s, but they were disappointing to me. I would often start my day listening to the Cool Sounds album. It was a great inspiration!

“In 1974, I found out that Albert was passing through the Midwest on a tour. I booked him at a club in Champaign, Illinois and I drove down there, about 120 miles, to see him close up for the first time. I was truly overwhelmed by the power of his music and his intensity. Along with Freddie King and Luther Allison, he was the most physical electric guitar player I ever saw. When he bent a string, he seemed to play with his whole body, from his toes on up to the top of his head.”

Despite his reputation as a live performer, Collins’ career was in free fall in the 70s. It was to Bruce’s delight, then, that a little bit further down the road he was in a position to throw the bluesman a lifeline by offering to cut a record.

“I was excited but nervous,” remembers Iglauer. “For one thing, Albert wanted an advance of $1,000! This was more than I had ever paid anyone up front to do an album (though those early artists ended up earning much more in royalties) and a lot of money for a label with one employee operating from my house, with only 12 albums out.

“But Albert was a hero for me, so it was really impossible to say ‘no’ – though I didn’t say ‘yes’ immediately; I was too scared about the money! Finally, when I decided to make the album, I thought that we might want to bring back those ‘frosty’ titles like his early instrumentals. I was thinking about some ‘cold’ words and I thought of ‘ice pick’. That led me to the idea of Ice Pickin’ as a title. I might have even envisioned the guitar plugged into the block of ice as a cover before we had recorded.

Released in 1978, Ice Pickin’ was, in Bruce’s words, “an immediate hit by Alligator and blues standards of the time”. Acknowledged by both critics and fans alike as the best album he’d recorded up to that time, it relaunched Albert’s career.

“The album has certainly stood the test of time. I continue to be very proud of it.” However, just because it was successful doesn’t mean it was an easy album to make…

“Preparing for the album was quite a challenge,” admits Iglauer. “One thing we learned very quickly was that Albert wasn’t much of a songwriter. Albert and his wife Gwen drove in from California just before rehearsals were to begin. He had promised to bring a bunch of original songs. Instead, he arrived with one instrumental idea, which became Ice Pick, and the words for Master Charge, which Gwen had written.”

A selection of covers were hastily pulled together: “As Albert had a dry voice, I thought of Lowell Fulson and remembered a song of his called Talking Woman Blues that we renamed Honey Hush. When The Welfare Turns Its Back On You was an obscure Freddie King recording that I knew. Cold Cold Feeling was, of course, by the creator of electric Texas guitar blues and one of Albert’s heroes, T-Bone Walker. And Too Tired came from Albert’s contemporary, Johnny ‘Guitar’ Watson. Both Albert and Johnny had been very influenced by Gatemouth Brown, so thinking of Johnny wasn’t much of a stretch.

“We cut Ice Pickin’ in three sessions, on May 22, 24 and 25, 1978, recording at Curtis Mayfield’s Curtom Studios where my favourite engineer, Freddie Breitberg, was working. It was a small room, and we had to put Albert’s very loud Fender Quad-Reverb amplifier in an isolation booth, which was actually a walk-in safe – the building had been a savings and Above loan [a type of bank] in the past. As usual, we cut totally ‘live,’ with the band all in the same room and Albert singing and playing his solos with them, not overdubbing later. The rapport was very good, with everyone laughing and joking constantly.”

Albert would go on to record three other solo records full of cold cuts for Alligator: Frostbite (1980), Don’t Lose Your Cool (1983), and Cold Snap (1986). He also took part in the well-received Showdown! (1985), a Grammy-winning collaboration with Robert Cray and Johnny Copeland. Full of piss and vinegar, Showdown! reflects the blistering sound of contemporary blues in the mid-80s, not too far down the road from a style being popularised by a young Albert King obsessive from Texas.

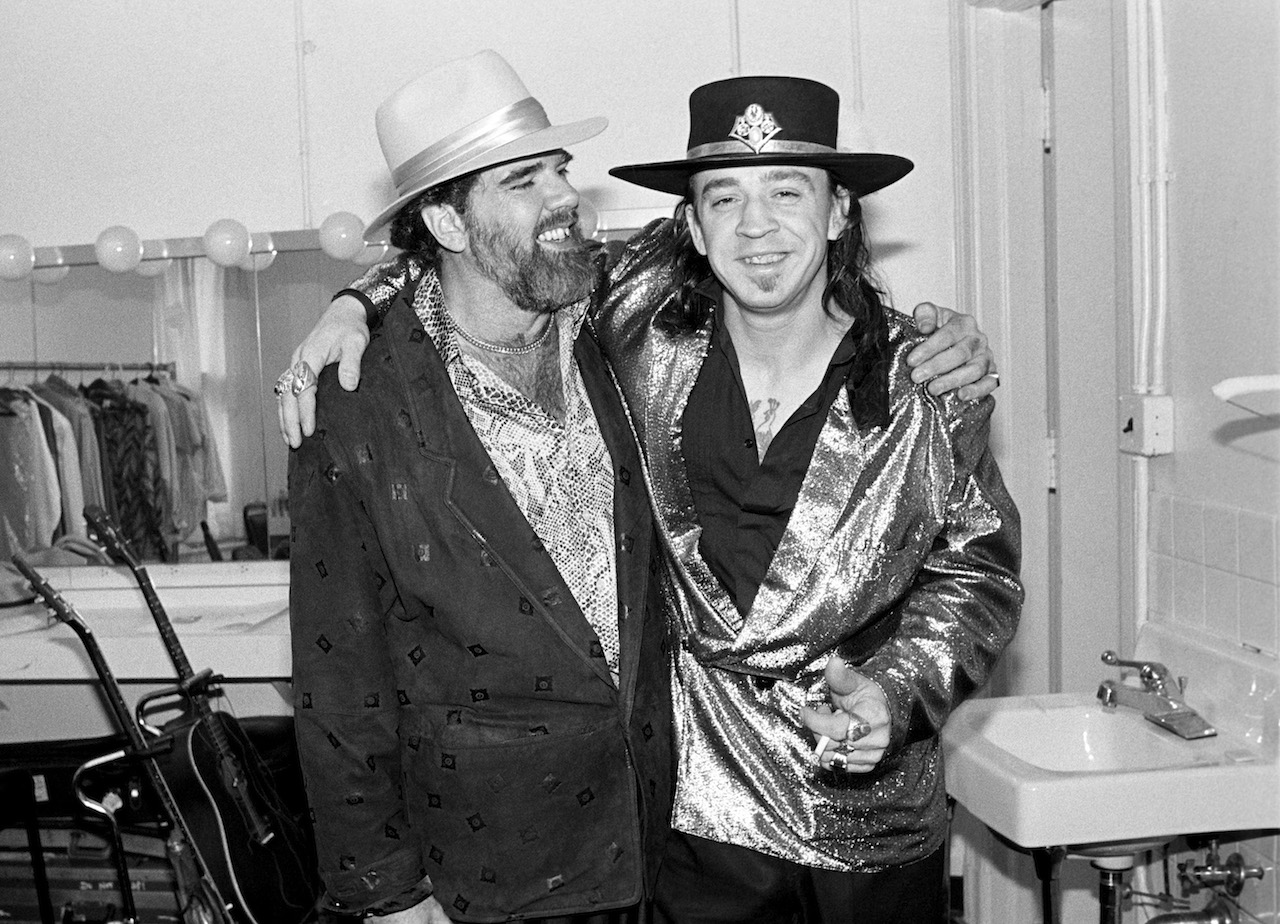

“The emergence of Stevie Ray Vaughan was a huge boon to the blues, though it also created a generation of less stellar SRV imitators,” says Bruce. “I admit that I didn’t get Stevie at first – he sounded like he was the world’s loudest Albert King imitator. Later on, as he developed his own sound and voice, it all became clear to me.

“I think his best music was yet to come, but I thought In Step was a major personal statement, especially with the lyrics of his originals. I knew Stevie from around 1979 and watched him grow as an artist. In 1984, he produced an album for us – Strike Like Lightning, 1985 – by one of his huge inspirations, Lonnie Mack, who was perhaps the first true blues/rock guitar hero back in the mid-1960s. Lonnie was a brilliant player and an incredibly soulful singer who grew up in southern Indiana, dirt poor. His inspirations on guitar were Robert Ward and Merle Travis, and his favourite singers were Bobby Bland and George Jones. So his music fused blues and country into rock’n’roll.

“His 60s singles, like Memphis and Wham, are amazing slices of guitar chops and energy. Supposedly the whammy bar is named after Wham, and it was definitely the first single that Stevie ever bought and learned.

“Lonnie lived in Cincinnati, Nashville, California, upstate New York and finally moved to the Austin area at Stevie’s insistence. They jammed together and when I decided to record an album with Lonnie, Stevie wanted to be in on the project. Lonnie decided to call him ‘producer’ but he was really more of a guest guitarist.

“His duets with Lonnie on Strike Like Lightning are amazing I think, as are Lonnie’s performances without Stevie. I was there for the recording of the album, and watched the two of them feed off each other’s guitar ideas. The whole album was recorded in just three and a half days and it’s stood the test of time.”

Hound Dog Taylor And HouseRockers, Strike Like Lightning and Ice Pickin’ are just a few of the classic albums that pack out the Alligator catalogue. But as we said before, this is not a museum exhibit. Bruce is all about finding the talent that will produce the future classics.

Few are better qualified to analyse the state of the current scene and what we need to do to keep moving forward.

“This is a critical time for the blues,” says Iglauer. “A lot of the established blues masters have died, and the international icons of the blues, BB King and Buddy Guy, are in their 80s and 70s respectively. It’s time for some new blues heroes to capture the public’s imagination. No single artist has emerged as the next giant.”

That’s not the only problem, either. As Iglauer explains, “Blues has gotten to be formulaic, and it’s necessary, if the blues is going to be more than a museum piece, for artists to create a ‘new blues’ that is true to the tradition without repeating it. Blues/rock and guitar heroes have gotten to be pretty formulaic too, and the flashy solo is not the answer. Ultimately, the music must have a blues message and a blues story, and a conscious connection to the tradition, but it doesn’t have to have a shuffle beat or try to repeat what Muddy, Wolf, BB, Albert, Freddie and so many others have already done to perfection.

“From the beginnings of blues until recently, blues evolved, though old styles of blues and new styles often lived side by side. I’m always looking for the artist who is going to create the new blues for the new millennium.”

So, should we be holding out for a new Muddy, Wolf or Hound Dog?

“All of those artists began playing in the black community for black fans, and began as local musicians playing for local fans,” Iglauer says. “They were consciously carrying on a tradition, never thinking about being recording artists or finding a national audience – just playing for their neighbours. That kind of culture is gone so I don’t think we’ll see other artists who perceive the blues like they did. But we can certainly expect more great blues artists, just ones who come with different cultural values and preconceptions.

“We’re all media babies now, and can hear music from all over the world. There are no isolated communities, at least in the Western world, where musicians learn from their elders and not from radio, the internet, recordings, video, etc. That’s how the blues started, but it won’t happen again that way. New blues will be affected by lots of other forms of music, from African to hip-hop to country.”

Whatever form the blues is going to take over the next few years, Bruce Iglauer and his label will be heavily involved in finding its stars… and its audience. You could say he stumbled into this whole record label thing, but he still enjoys the challenge of running Alligator some 40-odd years down the line.

“I love the music we record,” he says proudly. “I love being part of the creative process, which mostly happens when I’m producing – I’ve produced or co-produced about 125 albums. I’m not crazy about being a businessman, but I found out early on that I had to be really good at that or Alligator would fail.

“I’m proud that Alligator has made a modest profit almost every year of its existence. But the old rules don’t apply in this millennium, so I’m constantly keeping up with new technology, new ways people experience music, and trying to be savvy about the present and the future. Right now, no one in the record business really knows how to make enough money to pay for the cost of recording, promoting and marketing music.

“Tens of thousands of people can make their own records, but very few of them have the slightest idea how to get the public to know those records exist. The internet is not a miracle for musicians – it’s jammed with music that isn’t getting heard and that no one may want to hear.

“I have to be very smart and very driven if my label is going to survive for another 42 years!”