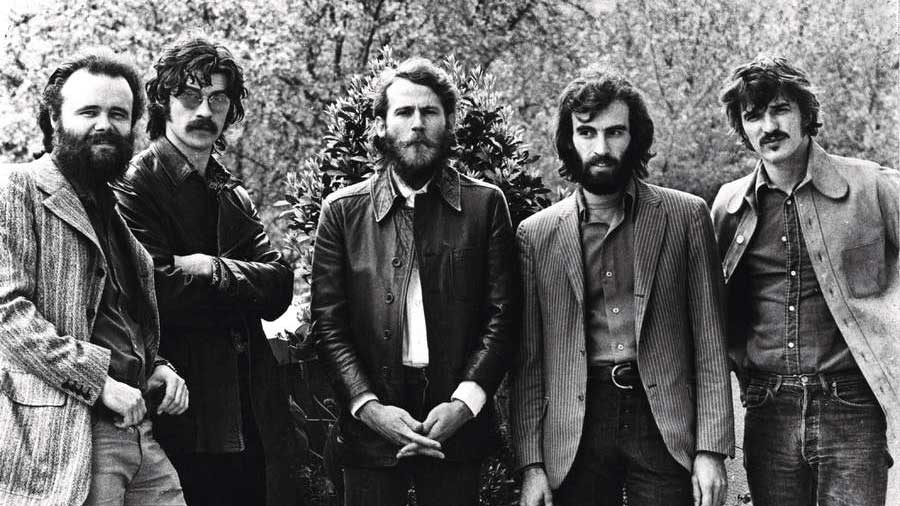

The Band were a paradox. Four-fifths Canadian, they nevertheless managed to embody a rural American mythos like no one before or since, their evocation of an imagined past rooted in a narrative tradition of country, blues, R&B, gospel, soul and rockabilly.

Equally contradictory was the fact that they were an intensely private bunch, driven primarily by the need to create, who became unwitting superstars in their adopted US, bowing out with one of the starriest rock shows of all time.

“It was a crazy ride, an unbelievable ride,” chief songwriter and guitarist Robbie Robertson told Classic Rock in 2019, reflecting on The Band’s sometimes troubled journey. “And a dangerous ride.”

That journey began in the early 60s, when the young quintet – Robertson, Helm, guitarist Rick Danko, piano player Richard Manuel and organist Garth Hudson, billed as The Hawks – toured the pit stops and bars of Canada backing rockabilly singer Ronnie Hawkins.

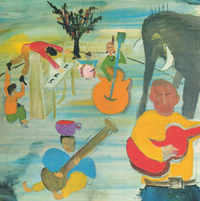

By 1965 they were Bob Dylan’s backing band. The relationship continued into informal jams in Woodstock (later issued as The Basement Tapes), before The Band struck out alone with 1968’s Music From Big Pink. That album set the template for their entire career: peerless ensemble-playing, down-home grooves, three distinct lead voices.

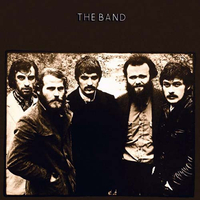

They peaked early; 1969’s self-titled album was a near-perfect expression of The Band’s creative vision. But it came at a price. Its huge success brought fame and wealth, plus its attendant insecurities, control issues and (for at least three members) grade-A habits.

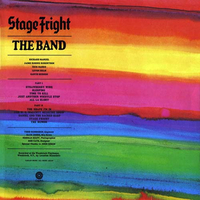

The following years were patchy. With relationships continuing to sour and sales on the slide, the group summoned strength for one final studio hurrah, 1975’s terrific Northern Lights – Southern Cross. A year later they retired from live performance, at The Last Waltz, a huge live blowout featuring a rollcall of famous guests. The Band reconvened, minus Robertson, in 1983.

Three years later, Manuel, still struggling with addiction, committed suicide. The remaining members eventually regrouped with auxiliary players later that decade, and went on to make three more studio albums before finally calling time after 1998’s Jubilation.

“At our best, The Band didn’t resemble anything else in the world, so it became something with its own identity and character,” explained Robertson, who passed away after a long illness in 2023. “That’s what we were shooting for."

...and one to avoid

You can trust Louder Our experienced team has worked for some of the biggest brands in music. From testing headphones to reviewing albums, our experts aim to create reviews you can trust. Find out more about how we review.