During their ten-year career, The Beatles were responsible for more seismic shifts in music than any other band. But they rarely get the credit for playing such a formative part in the development of rock music. Here are a dozen tracks that show just how important they were - and how much they rocked.

I’m Down

Tired of having Long Tall Sally and Twist And Shout as their usual set-closers, Paul McCartney decided to write something where he could really let rip and rival John Lennon as the Beatle with the rock’n’roll edge. “I could do Little Richard’s voice,” he told Barry Miles in 1997. “Wild, hoarse, like an out-of-body-experience.”

I’m Down (the B-side of the seven-inch of 1965’s Help!) was a last blast (for the time being) of the raucous stylings typified by Lennon’s versions of Money (That’s What I Want) and Chuck Berry’s Rock And Roll Music.

Taxman

From 1966’s Revolver, it’s the one time a George Harrison track would open a Beatles album, but what a statement, and what an album. As biting musically as it is lyrically – thanks to a little help from a reluctant Lennon – it snapped at the heels of HM Treasury and signalled the baby boomer generation’s post-austerity awakening. A wild guitar break (by McCartney, at George Martin’s request) and wired mod groove still pays off today.

Tomorrow Never Knows

Here’s where LSD, The Tibetan Book Of The Dead and one of Ringo’s malapropisms collide. Debuting a one-chord drone, Lennon attempts to sound “like a thousand Tibetan monks”, intoning lyrics inspired by Timothy Leary through a swirling Leslie speaker. Add McCartney’s avant-garde tape loops, processed beats and backwards instrumentation (that Taxman solo, reversed) and rock music shifted course once again.

Back In The USSR

This time Paul tried out his “Jerry Lee Lewis voice, to get my mind set on a particular feeling” on the lead track from The Beatles (1968). Fusing Chuck Berry’s Back In The USA with the Beach Boys’ California Girls, it sets off at quite a lick, tongue firmly in cheek as McCartney romanticises Iron Curtain life in a Cold War climate. Although ashram buddy and Beach Boy Mike Love was instrumental to the concept, in the US the track went over like a fart in church.

While My Guitar Gently Weeps

Here’s where George Harrison started to come into his own. Ignored by Lennon and McCartney who, he told the Anthology series, “were too busy cranking out their own tunes” on the White Album to indulge him his I Ching-themed rumination, he asked pal Eric Clapton to record the solo. Slowhand lays down an emotive lead on the Gibson he gave Harrison (nicknamed Lucy); the other Beatles play nicely in the presence of a guest, and Harrison notches up another gem with blues-boom cred.

- The top 10 best Beatles songs written by George Harrison

- 10 Things We Learned Watching The New Version Of The Beatles At Shea Stadium

- The 10 best Beatles songs as chosen by A Nameless Ghoul from Ghost

- The Thursday Death Match: The Beatles vs The Stones

Helter Skelter

The White Album track that influenced hard rock and heavy metal to come. Written after reading that The Who’s I Can See For Miles was the loudest, dirtiest song they’d ever recorded, McCartney decided to up the ante. In the studio, voices cracked, the playing became thrashier and the volume went up and up. Delirium hit the band. One take spun out to 12 minutes long. “I’ve got blisters on my fingers!” howled a bloodied Ringo, emphasising the track’s overall brutality.

Revolution (single)

So far the band’s public expression of politics had been suppressed, bar Taxman. Following anti-Vietnam war uprisings in the US and UK, Lennon got the bug. Two versions of Revolution were recorded: a laid-back stroller for the White Album, and a gutsy rocker that Lennon pushed as the next single to show his political hand. McCartney refused, concerned with a contentious image, and in ’68 it became Hey Jude’s agitated flip, all distorted screams and filthy blues swagger, marking Lennon out as a rebel with a cause within a new wave of electric protest songs.

Hey Bulldog

During the writing of Lady Madonna, McCartney started to bark over the piano riff, and this spring-heeled bluesy stomper was born. It was fleshed out quickly with fuzz bass, a brash, snarly solo and heaps of drums, and become a gritty highlight on the soundtrack to 1969’s Yellow Submarine.

Come Together

Now chums with the psychedelic spokesman whose Tibetan tome had made such an impression on Revolver, Lennon took up Timothy Leary’s presidential crusade slogan “Come together, have a party” and made a campaign song to kick off Abbey Road (1969). “It’s funky,” said Lennon of this goobledygook-laden slow ride. The style resonated with soul groups and hairy rockers alike, and included affectionate references to his bandmates: George the spiritual holy roller, Paul the monkey-finger bassist, himself the Ono sideboard, and Ringo – ‘got to be good looking cos he’s so hard to see’ as per his habit of hiding behind the others in photos.

I Want You (She’s So Heavy)

Eight minutes long, and constrained within an ominous repeated phrase, it was a giant leap from the buttoned-up cuteness of I Want To Hold Your Hand. Predating Black Sabbath’s creation of doom rock by several months, its intensity is alleviated a little by a Santana-like Latin blues section and some frothy Hammond breaks. By the end, the massed guitar build-up slathered in white noise and the jarringly abrupt edit add to the claustrophobia of a very weird, very grown-up love song.

Get Back

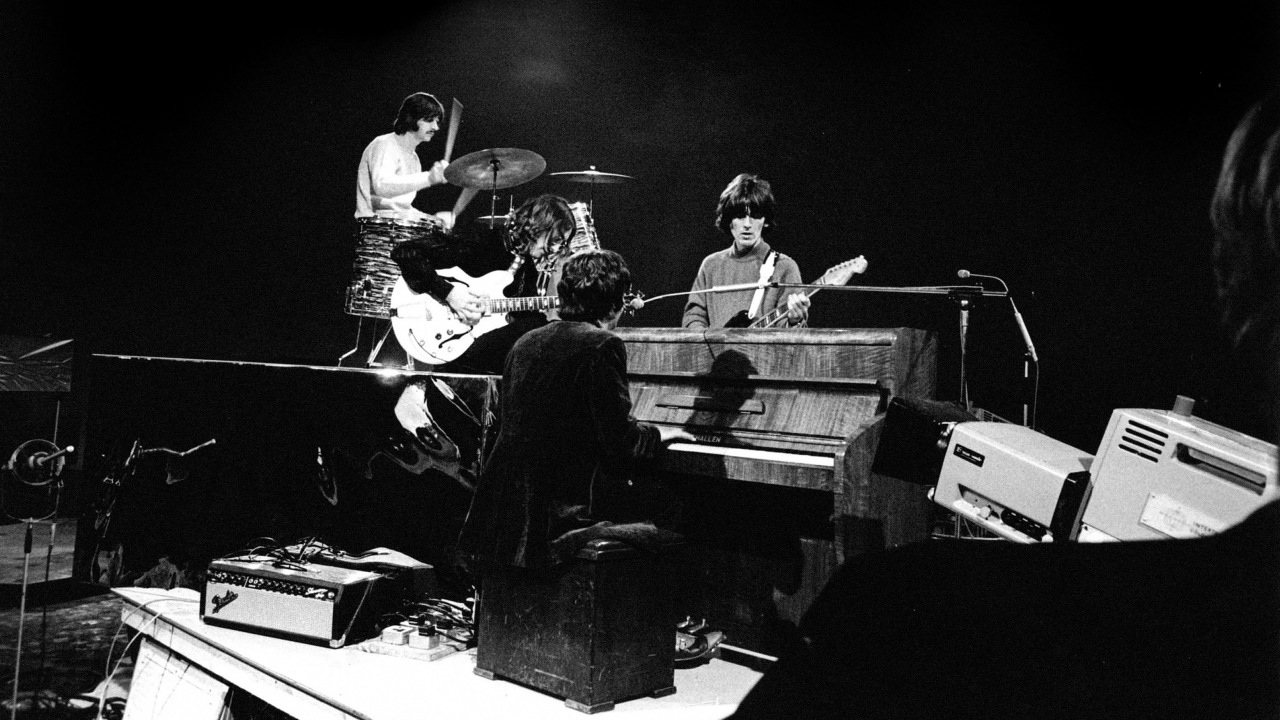

It was the beginning of the end, but one thing still united the band on 1970’s Let It Be: their R&B and blues roots. Get Back was a McCartney riff that grew out of “thin air, something to roller-coast on”. And when keyboardist Billy Preston turned up at the studio during a particularly stressful session, George Harrison leapt at the chance to use him. It broke the ice, and 27(!) takes later a magnificent, galloping soul-rock shuffle emerged from the wreckage. Its defining performance is as the climax to their impromptu final live show – the iconic rooftop gig of January 30, 1969, propelled by the excitement of the event and perhaps even a sense of relief.

Don’t Let Me Down

Another paean to Yoko from John, this time rooted in vulnerability and drugs. “It was a very tense period,” McCartney recalled in 1997 of songwriting sessions for 1970s Let It Be. “John had escalated to heroin and all the accompanying paranoias; it was a cry to Yoko for help.” With that cry, Lennon delivers his rawest, most honest vocal over a sweet ballad that follows the lead, mood-wise, of Fleetwood Mac’s Albatross. It was dropped from the album by producer Phil Spector after appearing as the B-side to Get Back in April 1969. But with the tenderness of the guitar and bass treatment, as well as McCartney’s impassioned backing, it’s their stand-out from-the-heart weepie.