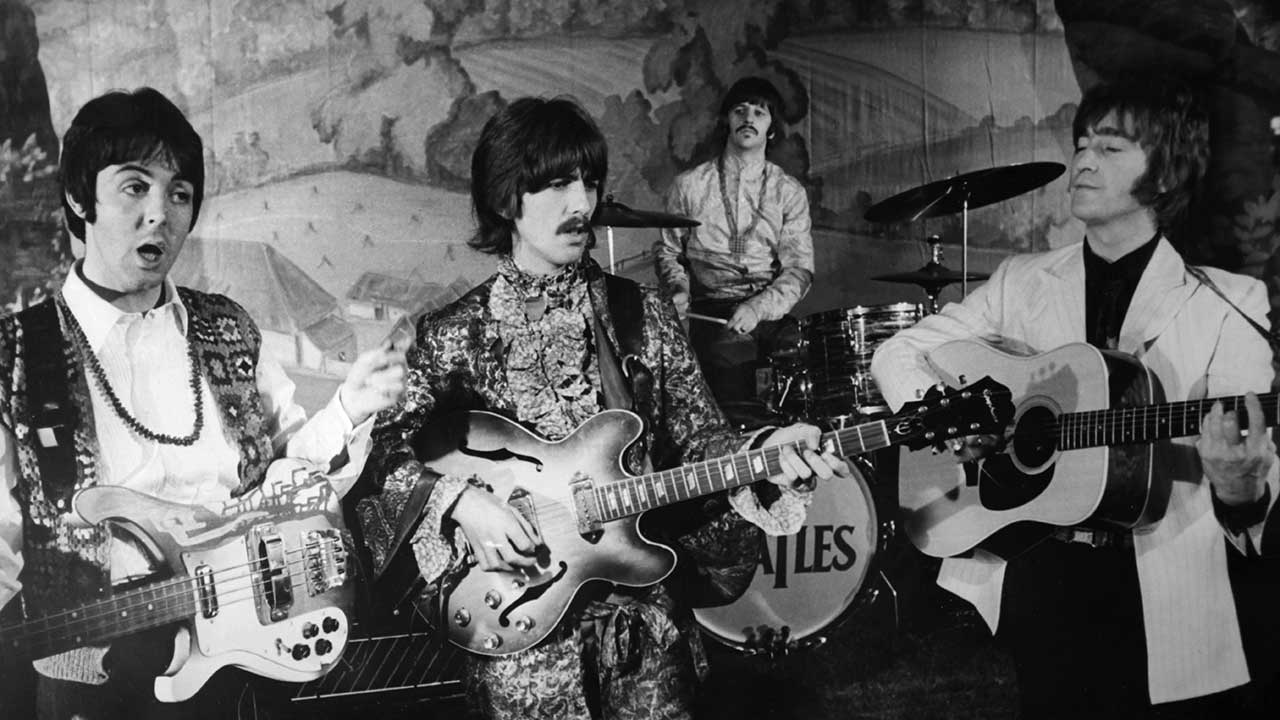

As the 60s swung about them and their iconic mop-tops grew increasingly shaggy, The Beatles enjoyed an unprecedented level of celebrity. Ubiquitous, universally adored, John, Paul, George and Ringo were the four most famous faces on the planet. Their uncanny ability to crank out concise, era-defining hits was the key to their success, and their world-beating charm was significantly enhanced by their easy camaraderie.

The Beatles were a gang; a gang that everybody wanted to join. Boys wanted to be them, girls wanted to be with them. But the private world that they shared remained seductively impenetrable. Somewhere between the musty bowels of Liverpool’s Cavern and the sordid fleshpots of Hamburg, they had developed an understanding that bordered on telepathy, an intuitive harmony that manifested itself in the creation of perfect pop.

But times change. Especially when you live your life under an unforgiving media spotlight, indulged, pampered, preyed upon by divisive sycophants, your judgment almost permanently refracted through a psychedelic prism.

Bound together by the captivity of fame, The Beatles came to resent their essential closeness. And by 1968, as they set about recording their eponymous double White Album, they were pretty much sick of the sight of each other. Just as telepathic harmony between the four Beatles had facilitated the creation of perfect pop, so growing disharmony bred the raw, discordant fury of rock.

The most significant of a series of events that activated The Beatles’ metamorphosis from exemplary pop group to prototype rock band was the death of Brian Epstein (above left). The band learned of their manager’s barbiturate overdose on August 27, 1967 while studying transcendental meditation with Indian guru Maharishi Mahesh Yogi in Wales. Within the week, they announced their decision to manage themselves.

Without Epstein’s cautious hand on the tiller, The Beatles were let off the leash creatively. Lennon was hit the hardest by his death, and as he enthusiastically self-medicated with lashings of LSD, the balance of power steadily shifted towards McCartney.

Epstein’s death left a gaping, substitute parent-shaped void in Lennon’s life (an unsatisfactory relationship with his absentee father combined with his mother’s early death left him vulnerable and in constant pursuit of a viable alternative). The drugs didn’t work, and his marriage to his first wife, Cynthia, was on its last legs. So when George Harrison suggested a trip in February 1968 to Rishikesh, in the foothills of the Himalayas, to attend a further course in TM under the tutelage of the Maharishi, John was the first to sign up.

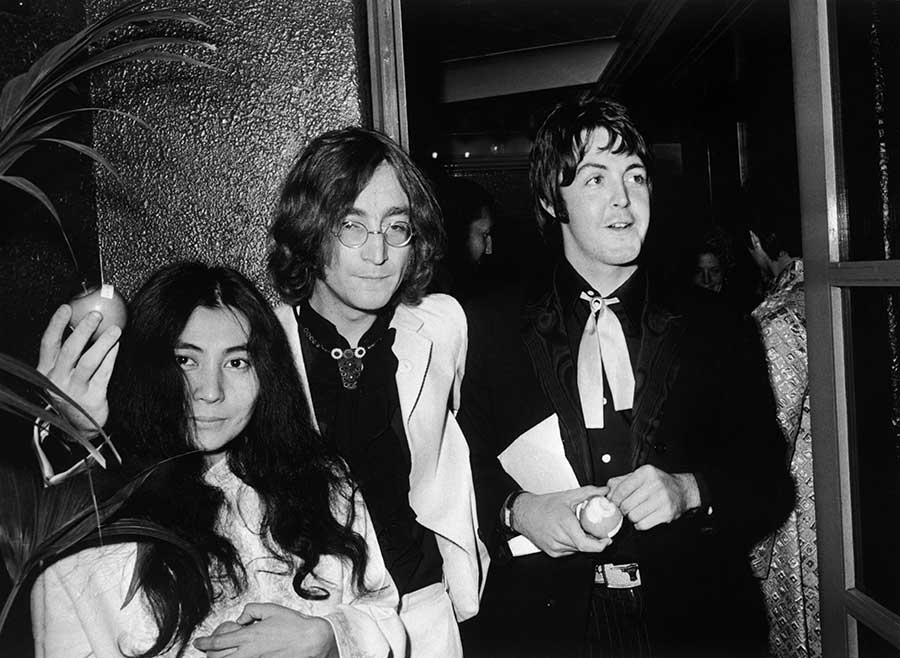

Soon enough, Paul and Ringo followed, along with wives, partners, Celtic folkie Donovan, Beach Boy Mike Love, actress Mia Farrow and her sister Prudence. John had considered inviting Yoko Ono, the Japanese artist he had met at an art gallery in November 1966 and with whom a mutual attraction had grown, but as Cynthia was also in attendance he thought better of it.

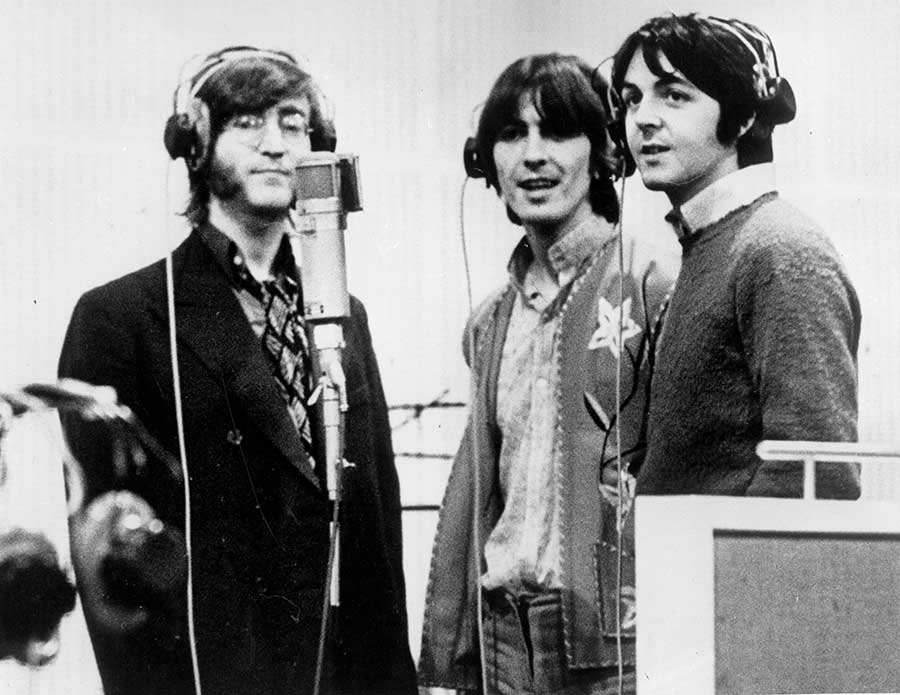

Newly decanted into a drug-free zone and with nothing other than TM to occupy their minds, The Beatles soon set about writing new material. And with the only Western instrument to hand being an acoustic guitar, the White Album’s sound was born of necessity. Donovan taught John to fingerpick and, utilising the technique, Lennon wrote Dear Prudence (an exhortation to the shy, young Farrow to join in with the transcendental fun) and Julia (ostensibly about his late mother, though also about Yoko, the ‘Oceanchild’ in the lyric; Yoko literally means ‘child of the sea’ in Japanese). In all, Lennon, McCartney and Harrison wrote 17 of the songs that would appear on the White Album while in India. And, for the very first time, even Ringo wrote one. He was that bored.

But John was still locked inside his own private hell. Trapped in a loveless marriage, obsessed with thoughts of Yoko and unable to sleep (an insomnia diarised in the White Album’s I’m So Tired), he wrote Yer Blues. Reminiscent of Fleetwood Mac and the other blues boomers, the song was indicative of the fact that Lennon was far from happy. “When I wrote ‘I’m so lonely, I want to die’,” he admitted, “I’m not kidding. That’s how I felt, up there, trying to reach God and feeling suicidal.”

Having travelled to India in search of direction and wise counsel from a parental figure, Lennon found only disillusionment. He left Rishikesh in a huff, accusing the Maharishi (falsely, as it turned out) of making a pass at Mia Farrow, an incident chronicled in the accusatory Sexy Sadie. “I was rough on him,” he said. “I always expect too much. I’m always expecting my mother and I don’t get her. That’s what it is.”

Within a month John and Cynthia’s marriage had ended and he was in a relationship with Yoko.

From the dawn of their celebrity, all four Beatles were individually famous. The public was soon able to differentiate which Lennon/McCartney compositions were Paul songs and which were John songs. George’s songs reflected another persona entirely, while Ringo was invariably gifted with the toxic chalice of Paul’s latest novelty song. In the absence of Epstein, and with disharmony in the ranks, the band split further apart into their constituent parts. Rather than drawing the band closer, India had only served to accentuate their differences.

In Rishikesh, away from the skewed reality of London, only George had found enlightenment (along with six songs). Ringo complained about the food and left early, followed by Paul who, between bouts of meditation had knuckled down to write a dozen or so songs. John’s experience may not have been terribly spiritual, but it was certainly profound. Off the acid and stunned into misery by the pin-sharp tedium of real life, he came to terms with the fact that his marriage was over and that he was falling in love with Yoko. During his stay, Lennon wrote 15 of what he later claimed to be some of his “best” and “most miserable” songs.

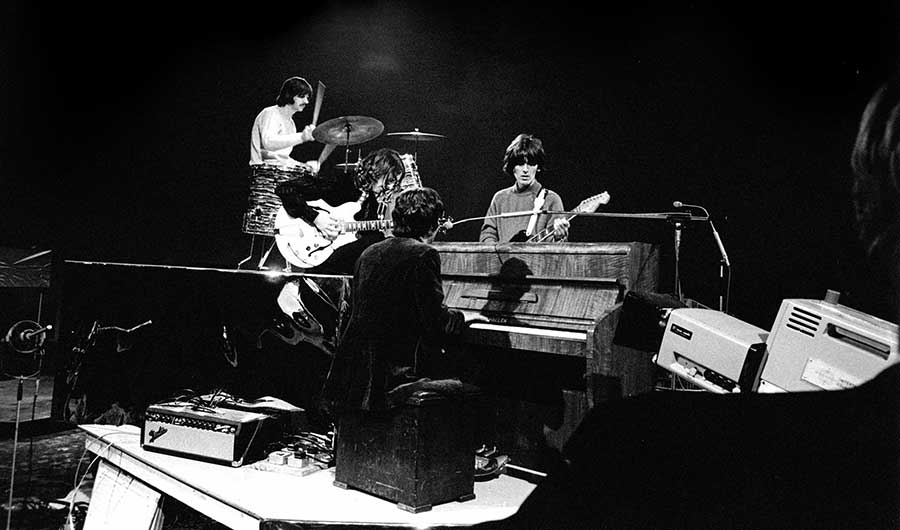

When the four Beatles finally took their individual songs into Abbey Road Studios in May 1968, they worked more autonomously than ever before. Abandoning the meticulous crafting that had served them so well on Sgt. Pepper, they jammed out a few backing tracks collectively, but generally worked individually.

The majority of the White Album was recorded as if four solo albums were being made simultaneously. McCartney was no longer editing Lennon and vice versa, Harrison was left to his own devices, and Ringo spent entire days twiddling his sticks in the studio’s reception; each songwriter took care of his own overdubs separately. A frustrated George Martin eventually abandoned production duties to go on holiday. His position as omnipresent fifth Beatle had been usurped.

While you can debate whether or not The Beatles were the first rock band, there’s no doubt whatsoever that Yoko was the first Yoko. John’s relationship with her was finally consummated just 11 days prior to the start of the White Album’s sessions at Abbey Road, and it caused him to re-evaluate his pampered existence. He had not been happy with Beatle-life for a long time, and his feelings were becoming clear as the band reconvened for the sessions.

“I was too scared to break away from The Beatles, which I’d been looking to do since we stopped touring [in ’66],” Lennon revealed in 1980. “I was vaguely looking for somewhere to go, but didn’t have the nerve - so I hung around. And then I met Yoko and fell in love: ‘This is more than a hit record. It’s more than everything…’”

Yoko, who wasn’t in the slightest bit impressed by Lennon’s Beatle status, opened his eyes to the vacuity of stardom. “That’s how The Beatles ended,” Lennon said. “Not because Yoko split The Beatles, but because she showed me what it was like to be Elvis Beatle and to be surrounded by sycophants and slaves who were only interested in keeping the situation as it was. She said to me:, ‘You’ve got no clothes on.’ Nobody had dared tell me that before.”

There was nothing particularly wrong with his marriage to Cynthia. It was, as he put it, “a normal marital state where nothing happened”. But Lennon wanted more, just as he always had. Above all else he wanted to be mothered. And with Yoko newly identified and installed as John’s perfect life partner, Cynthia wasn’t the only one facing redundancy. “Once I found the woman, the boys became of no interest whatsoever,” he said.

Their relationship was way beyond close. They had become two inseparable halves of a single entity, and Yoko a permanent fixture in the studio; she would be found sitting on top of a guitar amp or under the piano. When she became ill, a bed was installed in the studio. The besotted Lennon, oblivious to the feelings of his bandmates, stoked more resentment. The fact that the pair were now using heroin heightened tensions as Lennon became prone to temperamental outbursts.

The LSD-driven Technicolor pop lightness of Sgt. Pepper gave way to darker rock shades as the opiates held sway. Guitars distorted as moods blackened, and Yoko’s very presence initiated an edginess that mirrored the social chaos occurring outside of The Beatles’ bubble: a happy accident that only served to enhance the band’s rock’n’roll relevance.

To their credit, the others reacted to the Yoko-isation of the studio fairly well. They had to ask her to move every time they wanted to adjust their amps, but they generally favoured passive aggression over the frank exchange of fisticuffs you might expect of a band like The Who.

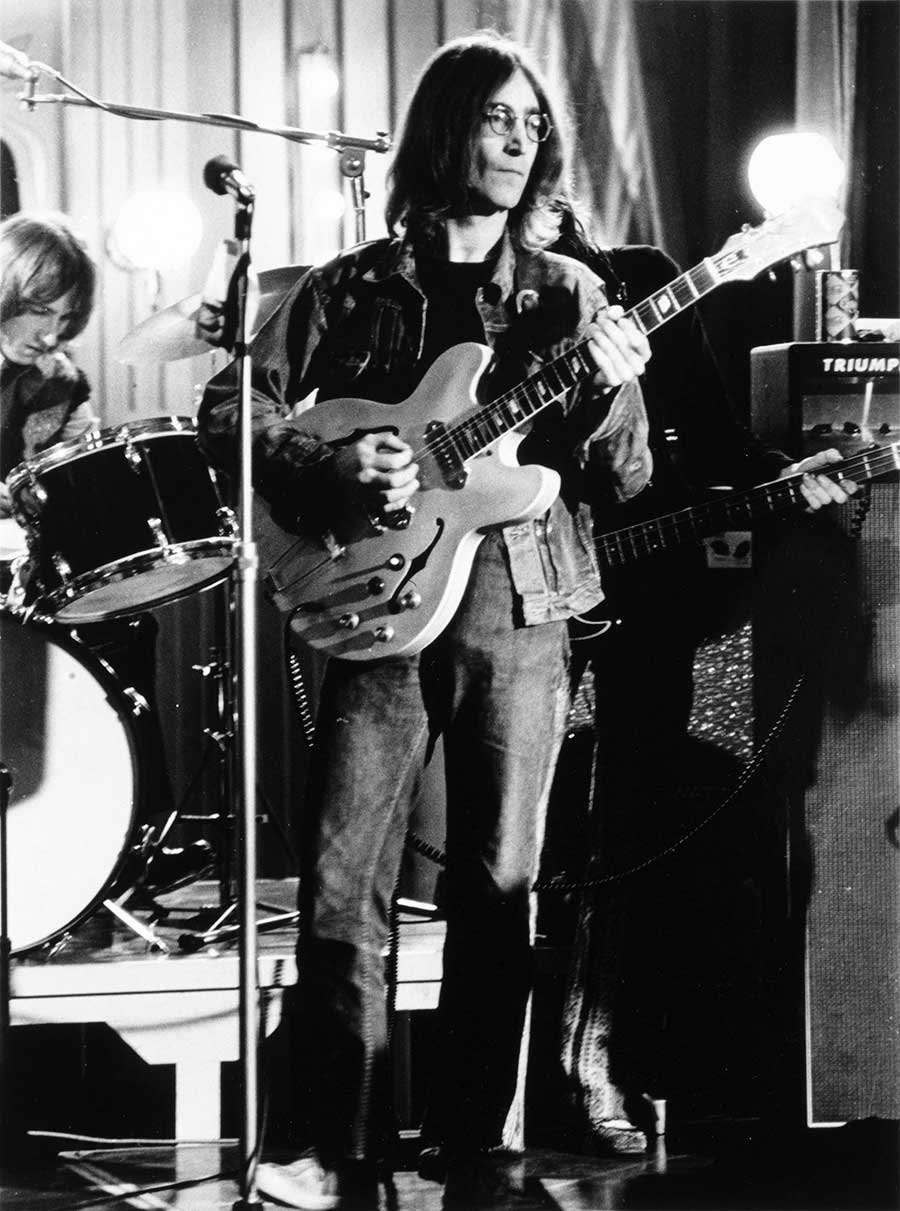

Lennon was hypersensitive to any negative reaction to his newly attached Siamese twin. The indignation of his fellow Beatles was at least understandable, but the negative press and public reaction to Yoko was not. It was this undue criticism (partly born of racism) that particularly rankled. A dormant hard-man persona came to the fore in Lennon. The moptop-era puppy fat was gone forever, now replaced with a lean, mean demeanour: Lennon the Peace Yob. It was the template for Liam Gallagher 25 years later, and a role Lennon himself would inhabit for the remainder of the decade.

Angry John was easily mistaken for Political John. Resentful that nobody liked his new girlfriend, he started ranting about peace, furiously planting acorns and shouting at journalists from bed. In so doing he inadvertently supplied the blueprint for Bono and every other rock star who assumes that just because they can sing in tune they’re Mahatma Gandhi, Winston Churchill and Jesus Christ rolled into one.

The onset of John’s apparent political conscience coincided with Yoko’s arrival. And as civil unrest continued to simmer across the globe, The Beatles suddenly found their voice. The White Album sessions commenced with Revolution, written by Lennon in the foothills of Rishikesh.

“I wanted to put out what I felt about revolution,” he explained in 1970. “I thought it was about time we thought about it. The same as I thought it was about time we stopped not answering about the Vietnam War.”

But there was ambiguity in Revolution’s lyric. John’s particular strain of revolt was to be purely humanitarian and strictly non-violent. Or was it? As he delivered Revolution’s pivotal ‘But when you talk about destruction, don’t you know that you can count me out’ lyric, he immediately followed it up with an entirely contradictory ‘in’. Conflicted? Perhaps. Mischievous by instinct? Definitely.

The first version of Revolution to hit record stores was faster and more aggressive compared to its bluesy, almost non-committal, White Album incarnation (titled Revolution 1). Re-recorded as an A-side, but demoted at Paul’s insistence to the B-side of the non-album Hey Jude single, this primal scream-propelled invitation to insurrection, replete with distorted guitar riff, managed to Trojan-horse its way into eight million homes. Heavy rock had barely been invented, but The Beatles, having nailed its key components, casually disseminated its message into every corner of the planet.

While John and Yoko were orbiting each other, McCartney was busy in his own world. A one-man Tin Pan Alley, McCartney has long been regarded as the soft pop cheese to Lennon’s hard rock chalk. But he could be just as hard, if not harder, than John. During the course of a particularly unguarded interview, ostensibly to promote Hey Jude in August ’68, McCartney flatly stated that: “Starvation in India doesn’t worry me one bit. Not one iota. It doesn’t, man.” He concluded: “The truth about me is that I’m pleasantly insincere.”

Never prepared to alienate the mainstream audience that had always formed The Beatles’ core constituency, McCartney’s stance in ’68 appeared counter-revolutionary next to Lennon’s. “People seem to think that all we say and do and sing is a political statement,” he said, “but it isn’t. In the end it’s always only a song.”

The final chapter in the Revolution saga, Revolution 9, was never “only a song”. It remains the White Album’s most ‘difficult’ moment. Eight minutes and 22 seconds of tape loops, sound effects and musique concrète, it was John and Yoko’s arty indulgence, and Paul argued against its inclusion.

John and Yoko’s relationship found its genesis in a shared fascination for the avant garde. In early May 1968, while Cynthia was holidaying in Italy, John invited Yoko over to his house. He played her tapes of his experimental home recordings, and over the course of the night the pair contrived to concoct an entire album’s worth of material. By morning they were a couple, and the commercially suicidal Two Virgins awaited its controversial release (it would emerge a week after the White Album, wrapped in the most unflattering nude cover in the history of sleeve art).

Enthused by their efforts, John and Yoko were keen to repeat the exercise, this time under The Beatles’ name. Two weeks later, with George Harrison along for the ride, they set to work on Revolution 9.

So why did McCartney take issue with what could have been construed as the most brave, progressive and genuinely revolutionary statement on the White Album? Surprisingly, it wasn’t down to the kind of musical conservatism one might expect of the man responsible for When I’m Sixty-Four. “I didn’t find that interesting,” he had shrugged of Two Virgins. “The music wasn’t shocking to me, because I’d made a lot like that myself.”

And he had. In January ’67 he’d recorded an avant-garde abstract sound collage of his own, the still-unreleased Carnival Of Light, for The Million Volt Light And Sound Wave show at London’s Roundhouse. Paul’s interest in the avant-garde significantly predated that of Lennon’s. It’s more than likely that his opposition to John’s Revolution 9 had less to do with its radical nature than with the fact it was an inferior version of John Cage’s Fontana Mix, released a whole decade earlier.

Up to and including Sgt. Pepper The Beatles were leaders. Revolution 9 recast them as followers. Yoko might have fast-tracked John into the avant-garde, but whether he had an actual aptitude for it was never considered. His Beatle status guaranteed Revolution 9 an audience, but didn’t guarantee that it was any good, or indeed any more valid, than the efforts of any other enthusiastic novice in the field.

Frank Zappa’s Mothers Of Invention had concluded 1966’s Freak Out (the very first double album, and the only one other than Dylan’s Blonde On Blonde released prior to the White Album) with The Return Of The Son Of Monster Magnet, a sound collage not dissimilar to Revolution 9. In March 1968 the Mothers’ Pepper-parodying We’re Only In It For The Money had featured the accomplished Varese-esque musique concrète of The Chrome-Plated Megaphone Of Destiny. Rather than being a brave new harbinger of an age yet to come, Revolution 9 was the least influential and, arguably, least original piece on the White Album.

The most enduring lesson Paul McCartney learned while serving his apprenticeship on the Reeperbahn was that a spoonful of sugar helps the medicine go down. If you want to keep your audience satisfied while you exercise your right to artistic freedom, he reasoned, you’ve got to give them a bit of what they fancy while you’re at it, no matter how excruciating it might seem.

“We’ve always been a rock group, The Beatles,” Paul said a week before the White Album’s release. “It’s just that we’re not completely rock’n’roll. That’s why we do Ob-La-Di one minute and this [the stripped-back 12-bar blues Why Don’t We Do It In The Road?] the next. When we played in Hamburg we didn’t just play rock’n’roll all evening, because we had these fat old businessmen coming in and saying play us a mambo or a rumba. So we had to get into this kind of stuff.”

With Lennon insistent on the inclusion of Revolution 9, the equally hard-nosed McCartney figured that the only way to render eight minutes of avant-garde medicine palatable was with an awful lot of sugar. He was compelled to balance out Revolution 9’s uncompromising approach with Honey Pie’s syrupy schmaltz, Martha My Dear’s music-hall bounce, and Rocky Raccoon’s kid-friendly yarn of feuding frontier folk. Then there was Ob-La-Di Ob-La-Da itself, a song memorably defined by John Lennon as “granny music shit”.

But in between the self-indulgence and the saccharine lay the sheer brilliance. The real reason we’re here: The Beatles’ enduring blueprint for rock.

With the White Album effectively delineated as four solo projects knitted together, the obvious question is: which one of The Beatles was it that first stumbled upon rock’s holy grail? And the answer? All four of them. Every one of rock’s key ingredients can be found scattered between Lennon’s Yer Blues, Harrison’s While My Guitar Gently Weeps, Ringo’s Don’t Pass Me By and McCartney’s Helter Skelter.

Yer Blues is the sound of pure disaffection, rock’s essential fuel. Lennon would retrospectively redefine its unalloyed passion as mere parody, a mocking comment on the burgeoning British blues boom. But there’s no doubt that its suicidal lyrical undertone was genuine. And whether he meant it or not, he certainly sounded like he did – especially on its key ‘feel so suicidal, even hate my rock’n’roll’ a line, a sentiment that encapsulated the disillusionment felt by a generation poised to abandon the utopian optimism of the Summer Of Love for its decidedly darker flip-side. The following year would see the doom-laden Yer Blues template – complete with the iron-booted bass drum thud that Ringo adopted across the entire White Album – echoed in the sound of Led Zeppelin.

Typically, neither John nor Paul took George’s compositions seriously. Frustrated, he persuaded his friend Eric Clapton to the studio, where the presence of an outsider made everyone shape up. “Paul got on the piano and played a nice intro and they all took it more seriously,” Harrison remembered. The resulting song, While My Guitar Gently Weeps, written with the Eastern concept of everything being relative in mind, boasts a brooding darkness that Clapton’s solos ignite and intensify. Rock guitar was never more passionate than this, and its overwrought crescendos set the bar high for all subsequent axe heroes.

- Paul McCartney – Egypt Station album review

- The Beatles - A guide to their best albums

- The Top 10 Best John Lennon Solo Songs

- Exclusive: see behind-the-scenes sketches from new Beatles graphic novel

And then there was Ringo. Carelessly benched by his self-absorbed colleagues, the drummer temporarily ‘left’ the band for a fortnight in August 1968, though not before recording Don’t Pass Me By. While Ringo finally nailed its lyric nursing a curry-ravaged intestinal tract in Rishikesh, he’d been working on the song for years. Ill-served by a throwaway, guitar-free, piano-heavy McCartney arrangement, the White Album’s incarnation of Don’t Pass Me By practically oom-pahs. Yet buried beneath the customary ‘comedy’ treatment accorded any Ringo vocal performance lay a southern rock exemplar par excellence. Neither his fellow Beatles nor George Martin realised the full boogie-rocking potential of Don’t Pass Me By’s driving, country-laced insistence. But the Georgia Satellites certainly did, granting Ringo’s pièce de résistance the barn-storming arrangement it deserved on their 1986 debut album.

With Lennon focused on Yoko, Harrison and Starr sidelined and George Martin’s influence receding, it was Paul who grasped the reins to gallop the White Album’s sound in the general direction of rock’s future.

As September wore on and sessions ground toward their fraught conclusion, the four Beatles set about recording the loudest and dirtiest performance of their career. Eighteen takes later, they had Helter Skelter, one of the prime progenitors of heavy metal.

“I read a review of a record [The Who’s I Can See For Miles] which said that the group goes really wild with echo and screaming and everything,” McCartney said in ’68, “And I thought, ‘That’s a pity, I would have liked to do something like that.’ Then I heard it and it was nothing like it. It was straight and sophisticated. So we did [Helter Skelter]…I like noise.”

While very much a group effort by comparison to the majority of the White Album’s performances, Helter Skelter was most definitely Paul’s baby. Both Helter Skelter and their other proto-metal experiment, the re-cut version of Revolution, attained a level of sonic extremity later disparaged by Harrison and Lennon.

“Revolution is pretty good and it grooves along,” said Harrison, 30 years later, “but I don’t particularly like the noise it makes. And I say ‘noise’ because I didn’t like the distorted sound of John’s guitar.” Lennon was even keener to distance himself from Helter Skelter. “That’s Paul completely,” he said in 1980. “It has nothing to do with anything, and least of all to do with me.”

Helter Skelter’s influence continued beyond heavy rock and metal into mid-70s punk. Siouxsie And The Banshees recorded the song for their debut album, 1978’s The Scream (though possibly more for its macabre association with Charles Manson, whose bizarre interpretation of the song’s lyric as an incitement to commit mass murder only served to accentuate its enduring appeal in certain quarters).

Perhaps more significantly, Helter Skelter’s violent nativity was witnessed by one of punk’s leading sonic architects. By this point, George Martin had effectively thrown in the towel by going away on holiday, though not before scribbling a quick note for his rookie assistant Chris Thomas to “make yourself available to The Beatles”.

Thomas (who eventually went on to produce Never Mind The Bollocks, Here’s The Sex Pistols) was to enjoy something of a baptism of fire: George Harrison running around the studio with a flaming ashtray on his head ‘doing an Arthur Brown’ while Paul McCartney screamed ever more demented vocal takes for Helter Skelter.

The 30 dizzyingly diverse components of The Beatles’ ninth studio collection were finally released on November 22, 1968. Housed in a plain white sleeve (embossed with the band’s name and a unique serial number) designed by pop-artist Richard Hamilton in collaboration with McCartney, the apparently eponymous set (a working title of A Doll’s House had been abandoned when Family released Music In A Doll’s House in July) was greeted by an unprecedented chorus of critical disapproval. Writing in the New York Times, Nik Cohn dismissed the album as “boring beyond belief”, while The Village Voice’s Robert Christgau called it “their most consistent and probably their worst”.

The truth of the matter was that the critics had, as usual, missed the revolution unfolding before their very ears. They focused largely on the ‘idiotic mediocrity’ of the ‘pretentious’ Revolution 9 and its counteracting anodyne ‘pastiches’. Interpreting The Beatles’ paradigm shift from overworked, ornate mini-symphonies to unfussy production values as sheer artistic indolence, they missed the crucial point that hindsight makes so plain: the White Album’s enduring influence on rock’s future lay in its embrace of the easy over the difficult; of visceral feel over cerebral contrivance; groove over gimmickry.

The Beatles found their way to the clear-headed simplicity of the White Album by pioneering methods that are now so familiar in the rock arena that they’ve become clichés. First in Wales, then in India, they were ‘getting their heads together in the country’; from acoustic demos at George’s to informal studio jams at Abbey Road they were ‘stripping back to basics’.

And not before time. Since Sgt. Pepper, pop musicians had seemed compelled to produce dense, psych-laced production numbers. The charts were clogged with countless kaftan-trussed quartets all desperately over-stretching themselves in the general direction of the cod-classical. This overwrought whiter-shade-of-pompous landscape, where proto-prog pretentiousness and lyrical gobbledygook prevailed, needed saving from itself.

The White Album arrived into 1968 like a breath of fresh air. It was just as influential and game-changing as punk would be less than a decade later. As The Beatles’ sound palette and cardinal frame of reference refocused away from the European orchestral tradition and back on to American roots music (country and blues, rock’s fundamental foundations), so vast sections of the contemporary musical community were almost bound to follow.

The Rolling Stones’ Beggars Banquet often gets the kudos for leading the way in this regard, but not only did The Beatles boast a far broader cultural influence in ’68, The White Album – though recorded later – also hit stores two weeks earlier. While The Beatles’ influence may have been diminished by a combination of the Paul-directed Magical Mystery Tour movie (the band’s inaugural artistic own goal, televised the previous Boxing Day – to almost universal bafflement) and a marked dip in John’s popularity since he’d fallen under the influence of ‘that woman’, they continued to outrank the Stones in the public mind.

The Stones, only just recovering from the disastrous, sub-Pepper catastrophe that was Their Satanic Majesties Request, were still widely considered to be slavishly following The Beatles’ lead in all things artistic, whether they’d already moved on or not. And while The Band’s Americana-birthing Music From Big Pink album had been released two months into the White Album sessions, and could therefore be considered as a potential influence on its roots-ward direction, the majority of its core material had been composed in Rishikesh four months earlier. (Even without benefit of the ornate curlicues of quasi-classical multi-tracking, Bach trumpets and reverse tape-loops, the stripped Beatles continued to be progressive with Lennon’s resolutely linear Happiness Is A Warm Gun casually challenging the very nature of song structure.)

They fashioned their look in a similarly simple style. The gaudy showbiz flash of the Pepper era joined the Epstein-dictated sartorial conservatism of their touring years on the cultural scrap heap. In their black waistcoats, white shirts, black hats, snake-hipped, low-slung, tapered and tailored flares, they looked more like a gang than like a marching band. Cuban-heeled, ankle-hugging Chelsea boots, mix-and-match moustaches and meticulously mussed hair suggested the brooding frontier cool of the American West, riverboat gamblers with issues. It was an enduring stylistic template for the likes of the Black Crowes, The Raconteurs and the Temperance Movement. The ’68 Beatles – a one-stop shop for 21st-century stylists – were rock-band-cool incarnate.

Looking back on the White Album, Lennon and McCartney were more than satisfied. “I always preferred it to all the other albums, including Pepper,” John said in ’71, “I thought the music was better. The Pepper myth is bigger, but the music on the White Album is far superior.”

“I think it was a very good album,” Paul agreed, but with reservations. “It stood up, but it wasn’t a pleasant one to make. Then again, sometimes those things work for your art.”

While it is indeed the grit in the oyster that makes the pearl, and great rock’n’roll is more often than not born of friction, antipathy and discord, any relationship based in negativity, even that of rock’s biggest band, cannot be sustained indefinitely.

Marginalised, underappreciated and made to feel redundant he may have been, but Ringo had already found that any decision to break-up The Beatles was way beyond his pay grade. George Harrison too: the guitarist ‘left’ the band for five days in January 1969, and was persuaded back only on condition that McCartney abandoned all plans for the band to return to the road.

In the end, though, there was no saving The Beatles. However much McCartney wanted the band to carry on, it was abundantly clear that Lennon, keen to investigate fresh artistic vistas with Yoko, had completely lost interest in continuing to work within the constraints of a four-piece rock band.

Lennon quit in September ’69, and McCartney, after months in denial, finally turned off the life support machine in April ’70.

The Beatles were a leviathan, a cultural colossus whose influence on their musical contemporaries was wholly unprecedented and remains unsurpassed. They were the first four-piece guitar band to smoulder moodily in leather jackets and shades; the first to grow their hair, to fly their freak flag, to tune in, turn on and flaunt it in the tabloids; the first to India; the first to soundtrack a Revolution; and the first to fall out over the first – and still the very best – Yoko.

With the White Album, The Beatles delivered all the necessary components for what we now know as classic rock, but the disharmony that facilitated its birth proved fatal. As John Lennon himself acknowledged: “The break-up of The Beatles can be heard on that album.”

Ultimately, having planted the seeds of sonic revolution in the fertile soil of the late 1960s, The Beatles’ work was done. With the spiritual progeny of their final incarnation on the rise, the artistically drained former Fabs were suddenly rendered old and in the way, an immovable reminder of a lost innocence, too ubiquitous to ignore, too enormous to eclipse.

For the green shoots of rock to thrive, The Beatles had to die.

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #202