For all the frequent brilliance of Neil Young’s albums, cherry-picking from them throws up its own set of problems. Distinctive, quixotic and, at times, downright infuriating, such is his uncompromising nature that even his own record company once threatened to sue him for deliberately making “unrepresentative” music.

A truly restless artist, there are various kinds of Neil Youngs: lone wolf, supergroup icon, Canyon hippie, garage rocker, country boy, grunge forefather... Will the real one ever stand up? Whether or not the definitive Neil Young really exists, one thing is certain: during a career spanning almost 60 years, he’s never been averse to taking the odd risk.

Born in Toronto in 1945, Neil Percival Young played in various Winnipeg garage bands in his youth, before striking out for LA in the mid-60s.

In 1966 he formed Buffalo Springfield with his friend Stephen Stills, Richie Furay, Bruce Palmer and Dewey Martin. Three albums later, torn asunder by the rivalry with Stills, Young quit for a solo career in-between membership of CSNY, alongside Stills, ex-Byrd David Crosby and former Hollies man Graham Nash.

The financial freedom gave his solo work limitless possibilities. By the early 70s he was the golden child of the Topanga Canyon set, the moody troubadour with the shaky voice and the bitter-sweet melodies.

But as his record company began plotting out a lucrative career as sensitive singer- songwriter, Young was already headed for the ditch. His bleak post-Harvest albums and a renewed acquaintance with old buddies Crazy Horse, marked by howling guitars and distorted feedback, proved he was a force that was impossible to tame.

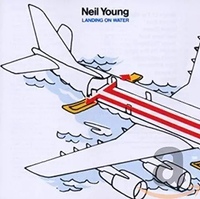

The 80s found Young in his own peculiar wilderness, producing a series of increasingly ‘difficult’ albums that tested the patience of diehard fans and confounded his record label, Geffen. In retrospect some of the bizarre experiments with electro-pop (Trans) could be forgiven once Young explained it was his way of communicating with his son, stricken with cerebral palsy. But it wasn’t until the early 90s, when he returned to the polarities of his best work (acoustic and raw electric) that he finally sealed the iconic status he enjoys today.

Young is as prolific now as he’s been at any time in his career, so what better time to assess the legend?

...and one to avoid

You can trust Louder Our experienced team has worked for some of the biggest brands in music. From testing headphones to reviewing albums, our experts aim to create reviews you can trust. Find out more about how we review.