In 2013, Classic Rock's much-missed sister magazine The Blues took a deep dive into the making of John Landis's classic movie The Blues Brothers. Writer Darren Weale spoke with actor and screenwriter Dan Aykroyd and to some of the musicians involved with the late John Belushi and the Blues Brothers: Curtis Salgado, Steve Cropper, Tom ‘Bones’ Malone and Lou Marini. It's quite a story.

The Dixie Square Mall that stood at the junction of 151st Street and the Dixie Highway in Harvey, Illinois had its grand opening in November 1966. By November 1978 it was abandoned. That’s not to say the old girl had outlived her usefulness.

The following summer, director John Landis rented the site to shoot a demolition derby of auto destruction for his latest project, a musical comedy starring John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd as ‘Joliet’ Jake and Elwood, The Blues Brothers. Landis had new shop windows and merchandise put in; he signed up dealerships to stock the car park and mocked-up showrooms with the latest in shiny and fat-rubbered Detroit steel.

The mall was eventually razed to the asphalt in May 2012 but Landis and his team of stunt drivers gave the demolition crew one helluva head start on that summer night back in ’79. The new cars and the mall would be wrecked in one spectacular money shot that was over in a matter of minutes.

By all accounts, that evening’s filming was bang on schedule but then some of the cast and crew began to notice that one of their number was missing. “Nobody could find John,” Dan Aykroyd tells The Blues. “I couldn’t find him on set or in my trailer, his trailer, anyone’s trailer. The radios were going crazy. It was 2am and we had to leave by dawn. Time and money were ticking away. I could just see $150,000 disappearing.

“I went to have a cigarette and stood under the stars, under the street lamps,” he continues. “I could see broken street lamps and a path of tufts of grass and broken glass, with the lights fading into the distance, like when Frank Sinatra is in his raincoat as he walks away. It was a logical walk to follow and I went down it. Lights in the homes around were extinguished. It was a dark suburban neighbourhood.”

As he sauntered along the quiet street, Aykroyd spotted something glowing in the distance.

“One light was on,” he recalls. “I knocked and a man came to the door. I said, ‘I’m sorry to disturb you, I’m looking for a missing member of our film crew.’ The man said, ‘You mean Belushi? He’s been here two hours, raided my fridge. He’s asleep on the couch.’”

That evening is Dan Aykroyd’s favourite memory of his late friend: “He was the guest who wouldn’t leave.”

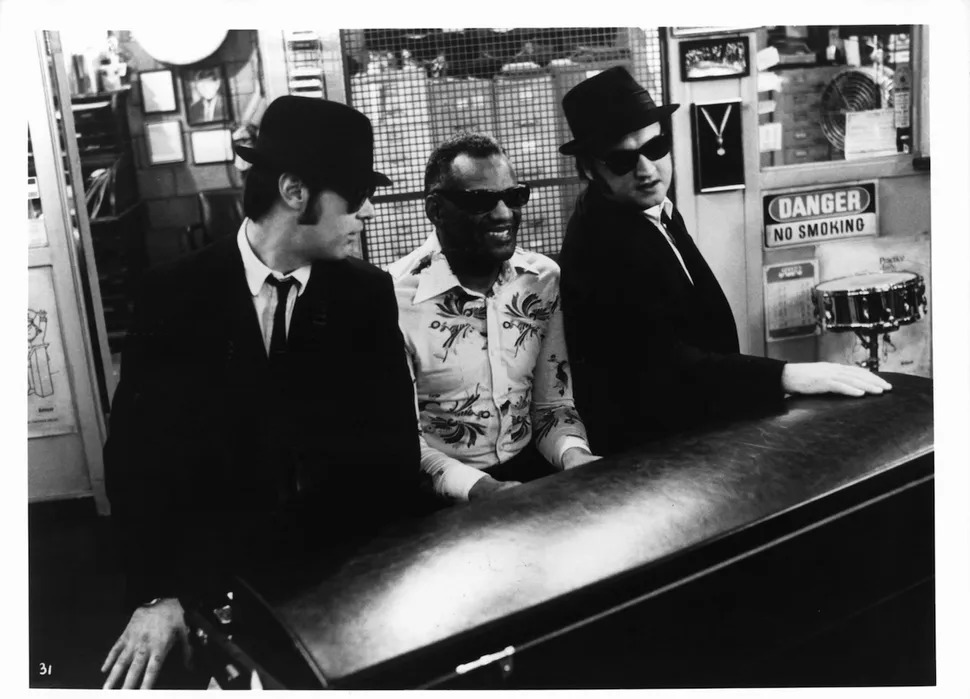

Debuting in 1980, The Blues Brothers movie is a light-hearted musical comedy that became a culturally significant event. It introduced a generation ignorant of the cultural significance of African-American music like jazz, blues and soul to legends like Aretha Franklin, John Lee Hooker, James Brown and Cab Calloway.

Picking up his brother ‘Joliet’ Jake Blues from prison where he’s served a three-year stretch for armed robbery, Elwood Blues has the audacity to turn up in The Bluesmobile (Illinois licence plate BDR529), a decommissioned ’74 Mount Prospect, Illinois Dodge Monaco patrol car.

He swapped their Cadillac for a microphone. The new motor’s attributes will come in handy when the brothers try to stay one step ahead of State Troopers, Illinois nazis and a pissed-off country band called The Good Ol’ Boys… and Jake’s homicidal ex-girlfriend, played by Carrie Fisher. Says Elwood: “It’s got a cop motor, a 440-cubic-inch plant. It’s got cop tires, cop suspension, cop shocks. It’s a model made before catalytic converters so it’ll run good on regular gas.”

The movie’s plot is simple. The boys return to the St. Helen of the Blessed Shroud orphanage in Calumet City, Illinois, where they were raised by Sister Stigmata – aka The Penguin – to find that she’s fighting closure. They need $5,000 to pay property taxes and stay in business. ‘Joliet’ Jake and Elwood visit the evangelical church service of Cleophus James (played brilliantly by James Brown), where Jake suddenly sees the light.

It’s a mission from God. Put their old band The Blues Brothers back together, put on a show and collect enough dough to save the orphanage.

All they have to do is find their old bandmates.

But hey, we’re getting ahead of ourselves here. As Steve Cropper told us, “The Blues Brothers was a band way before it was a movie…”

In 1975, Belushi joined the cast of comedy sketch show Saturday Night Live. His trademark skit involved dressing up as a bumble bee and singing Slim Harpo’s 1957 Excello Records B-side I’m A King Bee (‘Well, I’m a king bee, buzzin’ around yo’ hive’). It was Dan Aykroyd that sparked Belushi’s initial interest in blues music (he was bored of rock and hated disco) but singer and harpist Curtis Salgado gets the credit for fanning the embers.

“He sure turned John on to blues music,” acknowledges Aykroyd. “He steeped him in blues culture. I listened to him for my own harmonica practice.”

Salgado first met John Belushi in October 1977, when the comedian was in Eugene, Oregon, filming another John Landis-directed picture, National Lampoon’s Animal House. Although he was a familiar face on TV, Belushi’s portrayal of John ‘Bluto’ Blutarsky – a cross between “Groucho Marx and the Cookie Monster” – in the movie would prove to be the role that made him a king bee for real; a Hollywood A-lister. Salgado however, had no idea who this guy was.

“When he saw me play, he asked a local cocaine dealer and hanger-on, ‘Who’s that guy on stage?’” recalls Salgado. “I was with The Nighthawks with Robert Cray in the King Cole Room of the Eugene Hotel in Portland. I was in mid-set when a guy comes up and says, ‘John Belushi wants to talk to you.’ I say, ‘I’m singing. Fuck off.’”

Despite Salgado’s charming riposte, Belushi was determined to make his acquaintance.

“I jump off stage and head to a group of girls,” he recalls. “This guy grabs me and spins me around, says, ‘Meet John Belushi.’ This other guy reaches out his hand. I’m looking around over my left shoulder at the girls when Belushi says, ‘I love your music. It reminds me of a friend of mine. His name is Dan Aykroyd. He looks like you, he plays harp too.’ I think, ‘Great, that’s just what I need, another harp player.’”

Belushi explained that in addition to filming Animal House, he was still fulfilling his Saturday Night Live commitments by flying back to New York at the end of each week.

“I never saw it,” says Salgado of the show. “I’m a working musician. No time for TV. We have radio in our house.”

As he tried in vain to brush Belushi off, Salgado finally heard something that really snagged his full attention.

“I’m packing up my harps, trying to break free, when he says, ‘I’m going to have Ray Charles on the show.’ I turn and say, ‘You got to ask him about Guitar Slim and The Things That I Used To Do. You can hear Ray shout at the end of the record that it’s a take.’”

Ray Charles was in his early 20s when he arranged, produced and played piano on Eddie ‘Guitar Slim’ Jones’ million-selling 1953 rhythm and blues smash. By now warming to Belushi, Salgado dropped another nugget about The Genius into the conversation. “I said, ‘Do you know Ray plays alto sax? He did on Live At Newport [released on Atlantic Records in 1958] on a song called Hot Rod.’”

“After the show finished we partied a bit and he flew out,” says Salgado. “Saturday Night Live plays the following weekend. On the Sunday morning, rumours are spreading that Ray Charles played sax for the first time in 17 years on Saturday Night Live with the Saturday Night Live Band, as a guest. I think, ‘I did this.’”

Belushi was paying attention. He was getting hooked on the blues and Curtis Salgado was to become his dealer.

“John calls me up, says, ‘Let’s get together,’” he remembers. “I start bringing him my records: Fats Waller, Magic Sam, Sonny Boy Williamson. 30 records… a big pile. Howlin’ Wolf, Bobby Bland, Blues Consolidated. He dug Magic Sam. He absorbed it. He was serious – a very nice guy – and intense.”

Pretty soon, of course, Belushi wants to perform this music…

“We played the Eugene Hotel every Monday, called ourselves The Cray Hawks,” Salgado says. “A good crowd, a couple hundred. Then John Belushi began coming in. The word gets out and it was tenfold. He wants to sit in, asking me can he do Johnny B. Goode or Jailhouse Rock. I tell him they’re corny. I turned him on to Floyd Dixon’s Hey Bartender [released in 1954 on Cat Records]. Sure enough, he’s there next Monday. I said, ‘I’ll call you at the end of the second set.’ The place was now packed. The audience goes apeshit when I announce we’re doing a song with John Belushi. He gets up on stage.”

Belushi made the mistake of performing Hey Bartender in character to get laughs from the crowd. Salgado was not amused.

“I felt a little bitter,” he admits. “He’s doing the song with a gravelly voice and his hands clenched. I’m on harp and looking to my left, thinking, ‘Is that Joe Cocker?’ The audience are peeing their pants. I’m a bit disgruntled. That’s not a serious way to do the song.”

During the post-show analysis, Salgado gave Belushi a dressing down.

“He asks me, ‘What did you think?’”

“I say, ‘John, it’s Joe Cocker.’”

‘Yes, I do Joe on Saturday Night Live.’

“I punch his chest and say, ‘You need to do this from here [pointing at his heart] and be yourself.’ After that he didn’t mimic any more. He was himself.”

“John came back from Oregon with a lust for the blues,” remembers his widow, Judith Belushi. “He had tapes in his pockets and went to clubs.”

The Blues Brothers concept was conceived when Belushi and Aykroyd met in a bar a few years earlier. John would sing; Dan would play the harp. Also present at this time was Saturday Night Live musical director Howard Shore, who dubbed the union The Blues Brothers. The name hit the spot and stayed there.

The concept gathered momentum at the recording of Saturday Night Live.

“I made an arrangement for The Blues Brothers of the song Rocket 88 and we rehearsed it with the Saturday Night Live Band,” says trombonist Tom ‘Bones’ Malone. “We developed the characters and their steps, but we didn’t get on the show. Instead, we were asked to warm up the studio audience. Their reaction was reasonably good.

“The next week we thought, let’s do Hey Bartender,” he continues. “Again, we didn’t get on the show. Lorne Michaels, the show’s producer, said he didn’t see anything funny in The Blues Brothers. The next week we did nothing. The week after, he said, ‘The show is three minutes short, what can we do?’ John suggested The Blues Brothers. Lorne said, ‘You may as well make fools of yourselves, but if the show goes over time I’ll cut your part.’ We did it and had an amazing reaction, with cards and calls from the TV audience.”

Things started to move quickly. Record executive Michael Klenfner took John and Dan to see Ahmet Ertegün at Atlantic Records. He signed The Blues Brothers up. The boys now needed a band.

“John was the leader of The Blues Brothers Band,” says Bones. “He chose me, [pianist and future David Letterman Show band leader] Paul Shaffer and [saxophonist] Blue Lou Marini. He told me to choose another horn player. I chose Alan Rubin [aka Mr Fabulous] from the Saturday Night Live Band. [Legendary songwriter of Viva Las Vegas, A Mess Of Blues and others] Doc Pomus was John’s blues guru in New York and he chose Matt ‘Guitar’ Murphy to join the band. I recommended Donald ‘Duck’ Dunn and Steve Cropper.”

Dan Aykroyd remains grateful to Malone, Marini and Shaffer. “There would be no Blues Brothers without those gentlemen,” he says. “It was Tom Malone and Paul Shaffer who suggested we approach Duck Dunn and Steve Cropper, who were playing with Otis Redding. Then we became more than a comedy tribute. We became true blues with the full band and had the real essence of the music. Duck and Shaffer were both archivists and turned us on to so much. They were our musicologists, introducing us to songs like [James Brown’s ’69 hit] Mother Popcorn (You Got To Have A Mother For Me). They and Lou Marini helped us treat the music with knowledge, humour and with confidence that we were venerating it. They gave John confidence as a singer and me as an instrumentalist.”

Stax Records and Booker T & The MG’s alumni bassist ‘Duck’ Dunn and guitarist Steve ‘The Colonel’ Cropper initially thought the calls they received from John Belushi to recruit them for The Blues Brothers were bogus.

“I was mixing, and I tell the girls not to disturb me unless it is a friend calling me to go to lunch,” Cropper remembers. “When Belushi called, they figured it was important enough to put through, but I didn’t believe it was him. He’d be saying, ‘I want you in the band,’ and I’d say, ‘You’re not him!’ I pretty much hung up on him.

“The mix I was doing was for guitarist Robben Ford. He says, ‘What did he want?’ I say, ‘For me to go to New York and join The Blues Brothers Band.’ He says, ‘I’ll do it.’ I said, ‘No you won’t, I’m doing it.’ I finished the mix and arrived a day later than John wanted.”

Session saxophonist Tom ‘Triple Scale’ Scott and Saturday Night Live Band drummer Steve ‘Getdwa’ Jordan completed the line-up and The Blues Brothers began rehearsing for a run of shows at the Universal Amphitheatre in Los Angeles, opening on September 9, 1978 for comedian Steve Martin.

While choosing the set-list should have been easy – especially with a couple of Stax legends onboard – Aykroyd admits he made a few odd suggestions.

“We thought of doing a blues version of Stairway To Heaven,” he says. “Duck said no.”

“The Blues Brothers had been rehearsing with Duck a day before I arrived,” adds Steve Cropper. “I get there and Duck says to me, ‘These guys are rehearsing songs no one has ever heard of.’”

Stairway denied, the band replaced it with the 1967 Sam & Dave Stax classic, Soul Man.

“I say to Shaffer, ‘You know Soul Man?’” remembers Cropper. John says, ‘I can’t sing it that high!’ but we played it in the key of E instead of the key of G and we have done ever since. A better key!”

The live cut of Soul Man eventually peaked at 14 on the Billboard Hot 100. Cropper also had some thoughts on ‘Joliet’ Jake and Elwood’s stage presentation. “I saw them singing standing still and said, ‘You’ve got to move around more, like Sam and Dave.’”

The first Amphitheatre show was released as the 1978 Atlantic Records album, A Briefcase Full Of Blues. It was dedicated to Curtis Salgado.

“Nobody in the crowd expected to see Dunn and Cropper,” says Steve Jordan of the band’s live debut.

“We hit the stage on fire and played [Otis Redding’s ’65 B-side] Can’t Turn You Loose. The crowd was shocked and stunned. We just ripped it up. People were freaking out.”

“Afterwards, John pulled me into his trailer with Dan and opened a bottle of Dom Perignon champagne,” Jordan adds. “There was a knock on the door and Mick Jagger and Linda Ronstadt walked in. I’d seen that in my dreams. Jagger was all smiles – it was like a whirlwind, a congratulatory visit.”

“On the third night, I was the outside horn, nearest the audience,” remembers Marini. “I saw Jack Nicholson in the audience. He looked at me, lifted his sunglasses and went, ‘Wow!’”

When the decision was made to make a movie based around the band and its two leading characters, some line-up changes had to be made. Other commitments meant that Paul Shaffer, Steve Jordan and Tom Scott were unavailable. Willie ‘Too Big’ Hall stepped in on drums. Hall played with the Bar-Kays band at Stax and Isaac Hayes’s band The Movement; he played percussion on Hayes’ album Hot Buttered Soul and his Theme From Shaft.

Murphy ‘Murph’ Dunne took over on keyboards (the boys rescue him from lounge-band hell and his band Murph And The MagicTones). Tom Scott was not replaced, taking the band back down to a three-man horn section.

Dan Aykroyd spent six months writing the screenplay for what would eventually become The Blues Brothers movie. The result was a 324-page slab (bound in the covers of an LA Yellow Pages as a joke) that was too unwieldy to reproduce onscreen.

The movie’s director John Landis spent a fortnight whittling Aykroyd’s efforts into a workable script. The finished result contained some of the greatest movie dialogue ever. The Blues Brothers is second only to This Is Spinal Tap for killer quotes.

There’s the classic moment when ‘Joliet’ Jake and Elwood have the necessary scratch to save the orphanage and need to get it into the right hands. What ensues is an orgy of car crashes as they’re pursued by State Troopers – including John Candy as Burton Mercer – and Illinois Nazis, whose leader was brilliantly portrayed by Henry Gibson. And what dialogue kicks off the mayhem!

Elwood: “It’s 106 miles to Chicago, we got a full tank of gas, half a pack of cigarettes, it’s dark… and we’re wearing sunglasses.”

Jake: “Hit it.”

Then there’s the scene where the brothers seek out Matt ‘Guitar’ Murphy and Blue Lou Marini at Mrs Murphy’s (aka Aretha Franklin) Soul Food Cafe.

Nate’s Deli at 807 W. Maxwell Street in Chicago served as the backdrop for the exterior shots of the cafe. The interior was created on a studio lot. As Jake and Elwood approach the cafe, we’re treated to a performance of Boom Boom by Street Slim (played by John Lee Hooker); harpist Big Walter Horton (as Tampa Pete); Pinetop Perkins (as Luther Jackson) on electric piano; Willie ‘Big Eyes’ Smith on drums; guitarist Luther ‘Guitar Jr.’ Johnson; and Calvin ‘Fuzz’ Jones on bass. That’s Chicago blues royalty performing in an area that has been eradicated forever by modernisation.

The scene is a piece of blues history. The brothers head into the cafe and encounter Mrs Murphy. Matt ‘Guitar’ Murphy is the short order cook in the kitchen; Blue Lou Marini is washing the dirty dishes.

Mrs. Murphy: “May I help you boys?”

Elwood: “You got any white bread?”

Mrs. Murphy: “Yes.”

Elwood: “I’ll have some toasted white bread please.”

Mrs. Murphy: “You want butter or jam on that toast, honey?”

Elwood: “No ma’am, dry. [“I love dry white toast,” Aykroyd tells us. “These days I like to take it with some American Michigan sturgeon caviar on it.”]

Mrs Murphy turns her attention to Jake.

Jake: “Got any fried chicken?”

Mrs. Murphy: “Best damn chicken in the state.”

Jake: “Bring me four fried chickens and a Coke.”

Mrs. Murphy: “You want chicken wings or chicken legs?”

Jake: “Four fried chickens and a Coke.”

Elwood: “And some dry white toast please.”

Mrs. Murphy: “Y’all want anything to drink with that?”

Elwood: “No ma’am.”

Jake: “A Coke.”

When she realises the brothers intend to lure her husband and dishwasher back on the road, the foot comes down.

“Now, you not going back on the road no more. And you ain’t playing any more two-bit, sleazy dives. You’re living with me now… and you’re not gonna go sliding around with your white hoodlum friends.”

After a smoking blast through her 1968 soul hit Think, Aretha’s character loses her man to the mission from God. Blue Lou follows seconds later. “I pretended to be scared – I was supposed to be,” says Matt Murphy on his confrontation with an angry, full-throttle Aretha Franklin. “But I was having a ball! I was almost cracking up when I looked at her.”

Lou Marini recalls the days filming for a couple of reasons. First there was a practical joke: “The scene where I was washing dishes in the Soul Food Café, there were four or five guys. Landis and me, a camera guy, lighting guy, sound guy. Landis said, ‘I want you to do the dishes, do what you like with them, get angry, throw them, break them. Whatever you do, don’t look up till I say cut.’ I was washing an eternally long time. I looked up and they’ve all split. I yelled and down the end at the coffee shop I heard them cracking up.”

He was less amused by his portrayal during the Think routine. Some critics made reference to the fact that Marini’s head was out of shot as he danced on the cafe’s counter, playing his sax. He’d put a lot of effort into practising the nerve-wracking stunt.

“It was a little daunting,” he says. “The counter was raised up to four and a half feet up and was just two feet wide… and there were pots and pans down below.”

The reason his head was chopped? The set didn’t have a false ceiling. “The cameraman couldn’t use the angle as the top was unsealed and the studio was in view,” says Marini. “Landis took me to see a screening of the scene, said it was ‘spectacular’. He said to me, ‘It was great, right?’ I said it sucked. ‘I learned to play and dance and you can’t see my head.’ I was told, ‘You signed up for a lot of money and a little head, and that’s what you got.’”

The scene at Bob’s Country Bunker (where the waitress cheerfully informs the band they have both kinds of music: “country and western”) sees the band incite a violent reaction from the patrons.

As bottles smash on the chicken wire that isolates the stage from the paying customers, the band change tack and play The Theme From Rawhide and Tammy Wynette’s Stand By Your Man. The scene was based on real-life experiences and as Steve Cropper told Dan Aykroyd at the time, he had seen worse.

“I’ve seen guys shot, guys holding their guts and belly after being stabbed, people hit on the head with baseball bats – a lot of blood in the parking lot. By the time we did The Blues Brothers, Duck and I were both seasoned musicians. Dan went round interviewing the band and putting bits of useful information into the script.”

The tale of ‘Joliet’ Jake and Elwood Blues’ mission from God hit cinemas in 1980. The receipts for the ensemble talent and all those wrecked cars busted the movie’s budget by $10 million.

John Landis also encountered trouble getting The Blues Brothers into cinemas. For instance, Ted Mann, head of the Mann Theatres chain, was unconvinced that white movie-goers would be interested in a bunch of old black musicians. He also apparently didn’t want blacks congregating in predominantly white areas to see it.

Ultimately, The Blues Brothers only opened in half the theatres that a similar size movie would enjoy. Some critics hated the movie for its thin plot and reliance on car chases for entertainment, but they were in the minority. The finished product is a blast.

And despite Ted Mann and the critics’ best efforts, ‘Joliet’ Jake and Elwood Blues found their audience. The Blues Brothers made stars of Belushi and Aykroyd, allowing the latter to bankroll future box-office behemoths like Ghostbusters. It also reignited back-catalogue sales for James Brown, Aretha Franklin, John Lee Hooker and the other legends that appeared in the movie. Even blues and soul musicians that didn’t feature in the film felt the benefit of the public’s renewed interest in their brand of music.

The discovery of John Belushi’s lifeless body on March 5, 1982 in Bungalow 3 at the Chateau Marmont on the Sunset Strip in Hollywood put paid to any notions of a sequel to the movie. Belushi was only 33 years old when he succumbed to the effects of a speedball, a combined hit of cocaine and heroin.

Aykroyd takes the opportunity to pay tribute to his late partner in crime by remembering one of his favourite scenes in the movie – the attempt to persuade Alan Rubin to quit his maitre’d post at Chez Paul, the high-end restaurant where “Even the fucking soup is ten dollars.”

“The scene with John catching the shrimps in his mouth, he missed a few. I didn’t throw them all. Landis threw some. John was like a seal! He could catch shrimps, sing, dance, he was a real negotiator, actor, manager. He managed himself and the band brilliantly. A woman put too much heroin into his injection and his lungs and stomach were already weak, and she did three years in jail for it. The world lost one of its greatest talents ever at the age of 33.

“Maybe he was trying to numb the past, dull the present and look for comfort in the future. He found it there and it killed him.

“If he was here now, he’d be a top director on Broadway, putting on plays with great actors, part of the theatre world. He was very literate in his theatrical pursuits.”

The temptation to make a sequel did eventually prove too strong and Landis and Aykroyd reconvened for the ill-fated Blues Brothers 2000 in 1997. Despite some great musical performances, the absence of John Belushi was too big a hole to fill – even by John Goodman – and the movie bombed. Aykroyd’s intentions, as ever, were honourable.

“Getting the blues more widely known was part of the message,” he says.

The manifesto is right there in Elwood’s monologue that kicks off the first track on Briefcase Full Of Blues…

“Good evening, ladies and gentlemen, and welcome to the Universal Amphitheatre. Well, here it is, the late 1970s, going on 1985. You know, so much of the music we hear today is pre-programmed electronic disco, we never get a chance to hear master bluesmen practising their craft anymore. By the year 2006, the music known today as the blues will exist only in the classical records department of your local public library. Tonight, ladies and gentlemen, while we still can, let us welcome, from Rock Island, Illinois, the blues band of ‘Joliet’ Jake and Elwood Blues, The Blues Brothers.”

Thanks to ‘Joliet’ Jake, Elwood and their mission from God, The Blues Brothers band, even their ’74 Dodge Monaco cop car, the blues is still going strong.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock Presents The Blues issue 7, published in June 2013.