London, 1971. At the height of the progressive rock era, an American band named Eggs Over Easy found themselves stranded in the capital when the recording of their debut album was postponed. Holed up in Kentish Town, they persuaded the landlord of the nearby Tally Ho pub to let them perform their country-slanted down‑home rock in the back bar on Monday nights. Fortuitously, they were spotted by Dave Robinson, manager of United Artists recording act Brinsley Schwarz.

The Brinsleys were busy getting back to their musical roots and licking their wounds following the doomed hype of 1970, in which a planeload of British journalists were flown to the USA to witness the band’s lacklustre ‘world debut’ at New York’s Fillmore East. Robinson persuaded the Brinsleys to take a break from the college circuit and get on down to the Tally Ho.

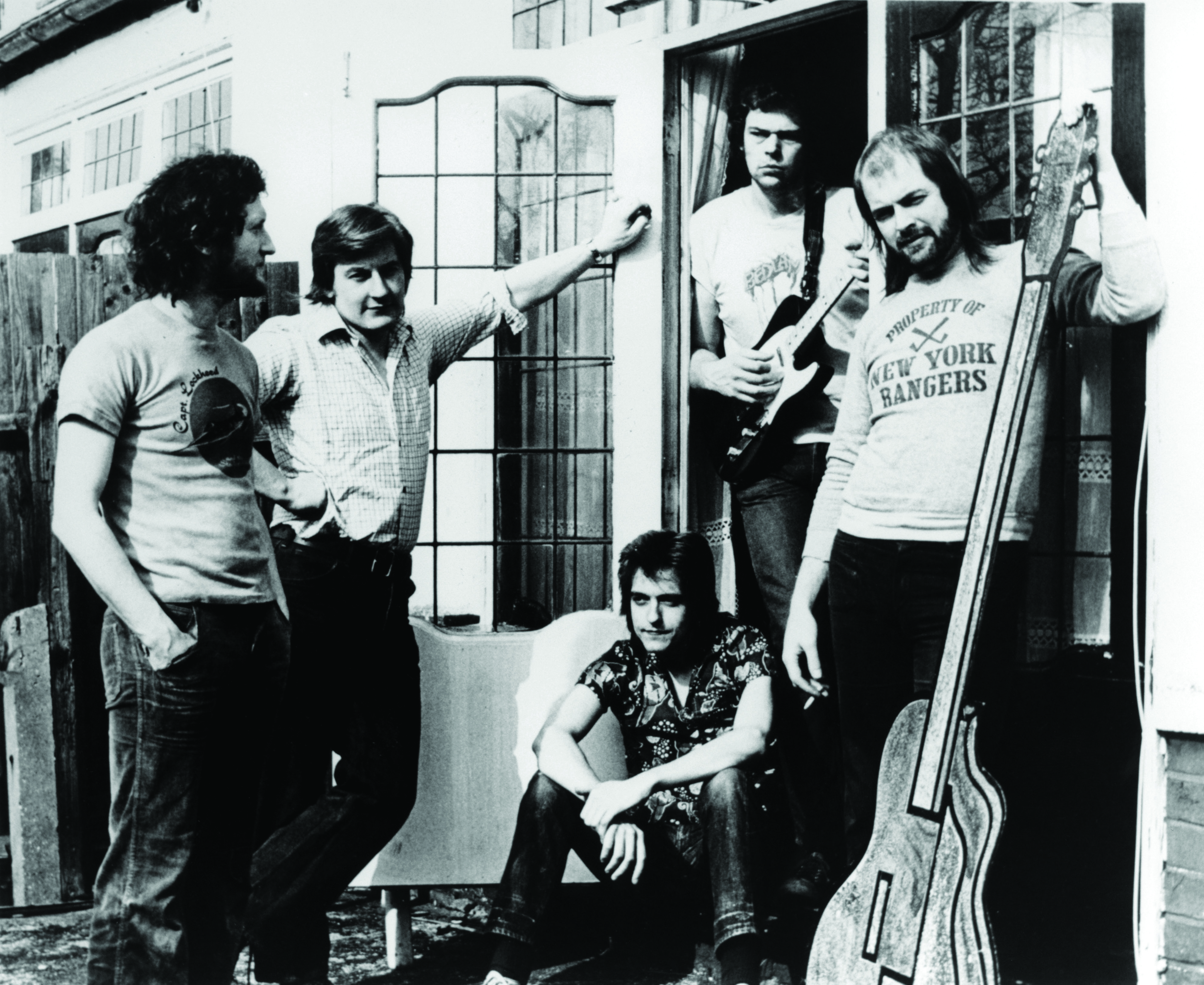

During the six months it took the Brinsleys to construct a ‘living jukebox’ repertoire, Irish band Bees Make Honey appeared, and a local musical community evolved. Someone dubbed it ‘pub rock’. Brinsleys’ roadie and keen guitar strummer Martin Belmont observed what was happening in the capital and sought to form a band with guitarist Sean Tyla, also a roadie (for Help Yourself). In fact, they would become ‘a band of roadies’ when Nick Garvey (a former Flamin’ Groovies equipment handler) replaced original bassist Ken Whaley. Only drummer Tim Roper had little experience of hauling amps and late-night motorway food, but he was rather better looking than the other three. The quartet would be known as Ducks Deluxe, taking their name from a slot machine (The Duck Deluxe) at the Severn Bridge Service Station.

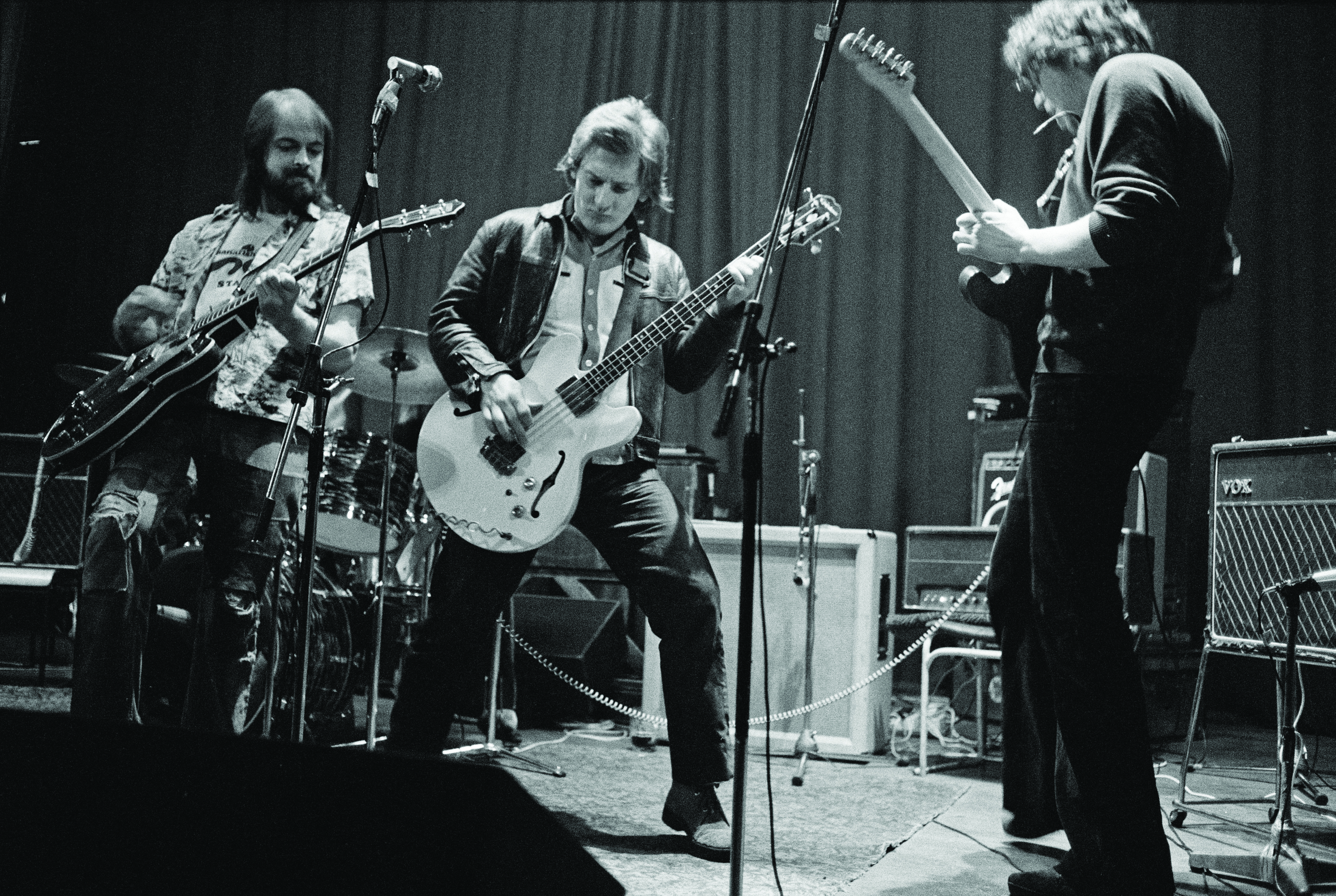

The Ducks, as they became known, had a straightforward musical policy – short, fast rock’n’roll songs with snarled vocals and maximum swagger. Sean Tyla, the group’s most prolific songwriter, was an ex-Tin Pan Alley song hustler, whose amusing 1960s experiences are recounted in his autobiography Jumpin’ In The Fire. “Sean told us he had been a member of Geno Washington’s Ram Jam Band and showed us a photograph to try to prove it,” recalls Help Yourself’s Richard Treece. “But even though the picture was badly blurred, we could see it was Pete Gage on guitar, and not Sean. We got used to Sean’s stories and he became a sort of court jester.”

Having spent a year observing the Brinsleys’ music at close range, Martin Belmont had formed ideas about the sound he wanted to make. He believed in writing short, direct songs, which made more sense than framing a song in a clever and interminable arrangement, as was the progressive norm at the time. “We were gonna be a song group,” says Belmont. “And as soon as I heard Sean’s songs, I knew we were going to rock.”

Nick Garvey, a former chorister and oboist, whose elder brother played French horn with the London Philharmonic Orchestra, remembers being pushed in the direction of the Ducks by Richard Ogden, a childhood friend who now worked for Liberty Records. “When my employment as the Flamin’ Groovies’ roadie ended, it coincided with Ken Whaley leaving the Ducks’ early line-up. Ogden told me, ‘You play the bass – go and see them.’”

Garvey hooked up with the Ducks at their squat in Prince Of Wales Drive, Camden Town, where they lived on crisp sandwiches and rehearsed day and night. They dared not dream of concert tours and record deals as such goals were a long shot for any unknown act. That’s because without an agent there was no live work, and without live work there was no agent, and without either, the record companies were simply not interested – such was the dilemma that prevailed until the London pub rock scene changed the rules.

The Ducks’ fortunes took an upturn when they met Dai Davies, a friend of the Brinsleys. Davies, a charming and persuasive Welshman, was looking to get into management following his stint as David Bowie’s publicist. “I introduced Dai to Sean Tyla and Dai liked Sean’s bulletproof ego and attitude,” says Belmont. “He offered to manage us.”

On a practical level, Dai’s car – an old Singer Vogue Estate – was just about capable of accommodating the Ducks and their mainly borrowed equipment, but Davies also knew people in the music industry. “Dai had a shedload of contacts and boundless enthusiasm,” says Tyla. “We were learning the game, but he already had a foothold.”

Ducks Deluxe were soon ready to go live, and where better to start than the Tally Ho? Playing in the smoke-filled bar to a small audience of Watneys Red Barrel-swigging regulars in October 1972, they blasted out their hard-driving punk rock, drawing on the intensity of the MC5, the street drawl of Lou Reed and the teen angst of Eddie Cochran. Within weeks, the Ducks built a loyal following and attracted a mention or two in Time Out, the gig-goer’s bible. As new venues sprang up all over town, so did previously unknown bands, such as Chilli Willi And The Red Hot Peppers, Kilburn And The High Roads and Ace.

To get more gigs, the Ducks knocked on doors and secured residencies at The Kensington, close to Olympia, and the Cock Inn on Holloway Road. A circuit was beginning to build, although some of the venues didn’t quite ‘get it’ – Tyla remembers the Irish guv’nor of the Cock Inn telling the band: “Listen lads, I’ve a cracking idea – I’ll get ye some bri-nylon shirts – they’re all the rage – in green of course. Now what do you think of that?” At the Cock Tavern on Kilburn High Road, Belmont recalls the landlord getting up on stage and berating the audience for only drinking half-pints. “He was furious. Talk about killing the vibe! He said, ‘If you lot don’t buy more drinks, I’m stopping this!’”

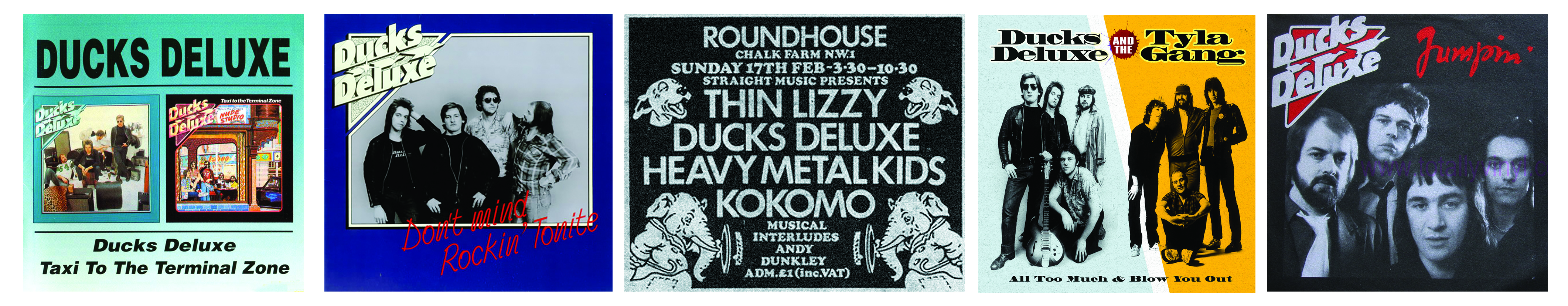

The Ducks became infamous for Tyla’s between-song patter. “Encore?” he would ask the audience at The Kensington. “You don’t fucking deserve one!” Despite Tyla’s often-offensive stage persona, their fan base multiplied and the music press posted rave reviews. Soon, the major record companies started to take notice, geed up by the irrepressible Dai Davies. In 1973, the Ducks signed with RCA Records. “A bottle of champagne, a cheesy photograph and the presentation of a large cheque sent us on our way to Saturn Sound in Worthing to record our first album,” says Tyla.

Based on the Ducks’ fondness for Toots & The Maytals’ Funky Kingston, one of its co-producers, Dave Bloxham, was hired to produce the debut album. The band had plenty of original material, mostly written by Tyla, including the anthemic Fireball and the swampy Daddy Put The Bomp, while Garvey’s Please Please Please is referred to by Belmont as “the slightly Beatle-ish one”.

The Garvey/Tyla rocker Coast To Coast became their first 45 and attracted radio play and a John Peel session, and the BBC filmed the band performing the number at The Lord Nelson.

“I had the chords and a rough idea of how the top line of Coast To Coast should go,” says Garvey. “I was thinking, ‘This is exciting!’ Sean said, ‘I’ve already got lyrics for this,’ and off it went. Of course, I don’t know how long it took Sean to come up with his lyric, but as he always had songs coming out of the ether, it probably took him five minutes, if that.”

Ducks Deluxe received good reviews but failed to ignite the charts upon its release in February 1974. “RCA didn’t understand Ducks Deluxe at all,” says Dai Davies. “Their plugger was Dave Most, Mickie’s brother. Imagine Dave Most talking to producer Ted Beston at the BBC about Ducks Deluxe! It was doomed. RCA in the States put the album out and wanted the Ducks to go on tour with Mountain, but we wanted to go on tour with The Band. We were so snobbish – we thought Mountain were crap!”

The Ducks toured relentlessly in their beaten-up Ford Transit, and in May 1974, they opened for RCA label-mate Lou Reed on a 19-date European trek. “Lou Reed was a dickhead on that tour,” says Belmont. “We got treated like shit, and not helped by Lou’s habit of disappearing at soundcheck time, thus cutting into our already pitiful allotted slot. He had the line-up with the twin lead guitars doing extended harmony lines, ruining the neat simplicity of Sweet Jane and the like.”

Following the Lou Reed tour, certain forces within the band thought that a fifth member, playing keyboards, might broaden the Ducks’ popular appeal. Tyla was very much against the proposal. “It was a moment of madness,” he says. “We were a two-guitar rock-a-boogie band and that was that. Nick wanted it – a lot – and I lost the vote. We didn’t need keyboards, but Nick was wholeheartedly for it. He just wanted to get more musical, which was fair enough, but at that point we should have changed our name to Kansas or Boston, because it lost what it was all about.”

Glaswegian Andy McMaster, who had once been in a band known as The (original) Motors with singer Frankie Miller, was recruited to tinkle the ivories in the summer of 1974. “When it turned out that Andy could also write catchy pop songs, like Love’s Melody, that made it even worse for Sean,” says Belmont.

McMaster’s arrival coincided with the preparations for the Ducks’ second album. Recording commenced that August at Rockfield Studios in Wales, with the legendary Dave Edmunds in the production chair. However, this was a difficult time for Edmunds, still recuperating from the excesses of hanging out with Keith Moon during the making of Stardust, a movie for which Edmunds was musical director. Recording was abated until November, but even then there were problems. “Dave was a genius, but he was burnt out,” says Tyla. “He made it through the recording, but I mixed it with Dave’s engineer, Kingsley Ward.”

To this writer’s ears, Taxi To The Terminal Zone, released in February 1975, benefits from McMaster’s involvement, because until Love’s Melody kicks in, it’s little more than an average collection of bar-room rock. “Nick Garvey loved Love’s Melody and sang it,” says McMaster. “But the biggest cheer came from RCA, who saw it as a chance to get their money back.”

Garvey’s soul ballad I’m Crying is brave, with a strong vocal, but suffers from poor production. Things pick up with the Flamin’ Groovies’ totally apt Teenage Head. Tyla’s Rio Grande is Dylanesque Americana, an ambitious soundscape with Edmunds on pedal steel guitar. The closing Paris 9 evokes the band’s frequent Euro tours, but almost inevitably the album was a commercial flop.

The Ducks’ line-up was already crumbling, not helped by their relocation to a rented house in Hendon, in the shadow of the M1, where leader Tyla drew the short straw and was relegated to the smallest bedroom. Nick Garvey and Andy McMaster had quit between the recording and release of Taxi, whereupon Tyla resolved to revert to a four-piece band. “It was always Sean’s band, both from a songwriting point of view and his performance attitude,” says Garvey. “He wrote proper songs, with a proper structure, and had a nice, if obsessively American, way with lyrics.”

Through an advert in the venerable Melody Maker, Tyla brought in bassist Micky Groome, and the revitalised quartet recorded four tracks at Pathway Studios. These included a cover of the Bobby Fuller Four’s I Fought The Law, which RCA were persuaded to release as a 45, the Ducks’ last on the label. Drummer Tim Roper was next to leave, and sadly died in 2003.

The early months of 1975 saw a number of the original pub rock groups disband, including the Brinsleys, the Kilburns and Chilli Willy, but before the Ducks threw in the sweaty towel, they limped on with an 11th-hour line‑up that included drummer Billy Rankin and guitarist Brinsley Schwarz, both from the band of the same name. Schwarz had been drafted in by Dai Davies to help ticket sales in Europe, where Skydog Records had released the Pathway tracks on an EP entitled Jumpin’.

The first thing Tyla knew about Schwarz’s inclusion on the Dutch leg of the tour was when he saw a concert poster bearing the guitarist’s name. “I was absolutely furious,” says Tyla. “It was my first ever encounter with any form of manipulation in the rock’n’roll business, apart from Dai booking us into the London Gay Ball without telling us and waiting until the soundcheck to inform us that our name for the night had been changed to The Iron Boys. But everything would be all right because we were getting thirty quid.

“I guess we split because RCA dropped us,” continues Tyla. “Dai faded into the shadows and we lost our drive. We were successful in France and it was suggested that we concentrate on that, but I wanted to get a new band together and so it went.”

Tyla’s new band would become The Tyla Gang, who launched in late 1975 and went on to record for Beserkley Records. Meanwhile, Martin Belmont and Brinsley Schwarz formed The Rumour, the explosive backing group that helped to propel singer and songwriter Graham Parker towards great acclaim.

In 1977, Nick Garvey and Andy McMaster regrouped as The Motors, a guitar-heavy quartet specialising in forceful, harmony-infused rock that in some respects fulfilled the promise of Ducks Deluxe. The Motors’ four-year career was not without its opportunities: Robert John ‘Mutt’ Lange and Jimmy ‘Beats’ Iovine were two of the world’s most successful rock producers, and they both got to work with The Motors. Lange produced the 1977 debut, The Motors 1, featuring the standout tracks Bring In The Morning Light and Dancing The Night Away. Iovine was responsible for their 1980 swansong, Tenement Steps, containing the epic Love And Loneliness.

Strangely, both of these albums flopped, so it’s ironic that the band’s intervening release, Approved By The Motors, which started its life at the tiny eight-track Pathway Studios, was the album with the hits. Airport, which McMaster says he’d had in his back pocket for five years, and the Foundations-like Forget About You saw The Motors on Top Of The Pops, but they too would soon disband and fade into obscurity.

And what of the Ducks? They called it a day just in time to avoid a trouncing from the punk bands of 1976, yet their pub rock crusade somehow facilitated the acceptance of punk. Their music was often fast and raucous, and their manager, Dai Davies, gave Dr Feelgood their first London pub gig. It was the Feelgoods who primed a new young audience for the Sex Pistols and The Clash.

Outwardly, the Pistols may have preferred to disassociate themselves from the pub scene, but they weren’t above using some of the venues, such as The Nashville, to establish their reputation. There were even those who didn’t find anything particularly new in the Pistols’ approach.

“I thought the Sex Pistols with Glen Matlock were a pretty good group, a bit like The Stooges,” says Dai Davies. “But in reality, the Sex Pistols were no less of a pub rock group than Ducks Deluxe, only a bit younger.”