This article first appeared in The Blues #3, September 2012.

Stumbling into the dimly lit Bluesday R&B club at the Railway Hotel in Harrow in early 1964, film-makers Chris Stamp and Kit Lambert were in search of something special, but weren’t entirely sure what. Lured in by the row of Italian scooters parked outside the northwest London pub, they found the promoters – teenage mods – packed into a hellishly hot, smoky basement.

On stage are a loud, aggressive four-piece band, fronted by a whippet-thin, blond-cropped singer in a striped T-shirt and bluebottle shades who seems intent on using his maracas as an offensive weapon.

Every so often, the guitarist windmills his arm and hoists his Rickenbacker up to his regally prominent nose, almost high enough for the guitar head to poke through the low ceiling.

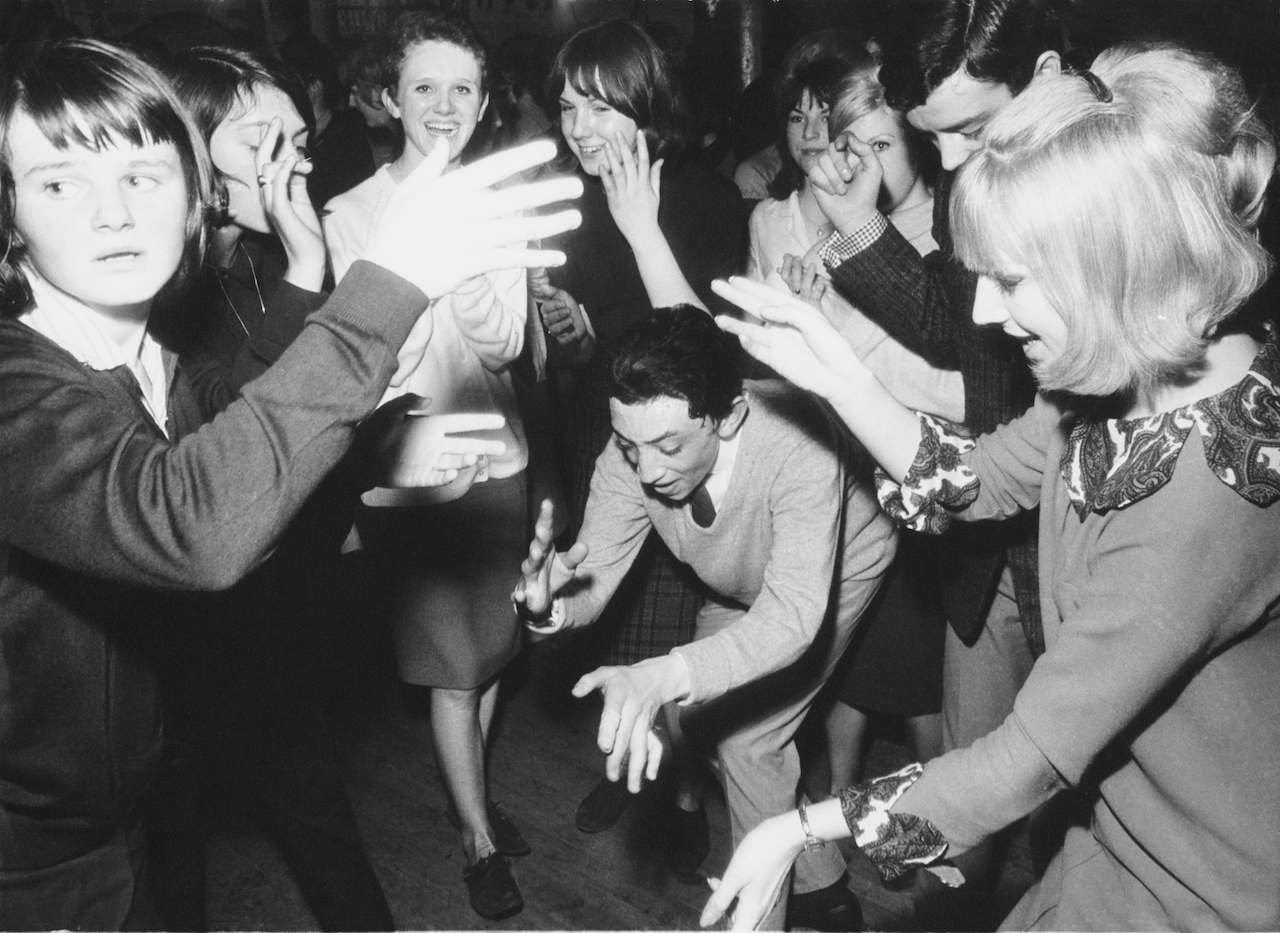

The audience, dressed in a similar fashion to the musicians, are dancing with their backs to the stage, not as couples but in small groups of boys and girls, unsmiling and with intense concentration on intricate steps: a blur of French crops, Vidal Sassoon bobs, white jeans, suede desert boots, criss-crossed legs and flailing hands. Being able to dance on floor space the size of a postage stamp while simultaneously chewing gum at lightning speed seems mandatory.

After this total assault on their senses, the out-of-place interlopers know they’ve found exactly what they’re looking for. The band are called The High Numbers and they’re performing a driving R&B version of Ooh Poo Pah Doo, a song originally released in 1960 by Louisiana blues singer and songwriter Jessie Hill.

Like the band’s jive-talking publicist Pete Meaden, Lambert and Stamp (who later take over the band’s management) surmise correctly that kids are no longer interested in tapping their toes while a bunch of bearded old farts in bowler hats and waistcoats play trad jazz. Mods wanted the blues, but they wanted it to be danceable, and preferably played by individuals who dressed as sharply as themselves.

Not only are The High Numbers covering the R&B songs they’d been hearing in mod clubs such as The Scene in Soho, the group are also inspired by the showmanship of American musicians such as James Brown – unlike the tame, well-scrubbed Merseybeat bands of the day, who stood grinning inanely into the TV cameras on early editions ofTop Of The Pops.

In July 1964, Meaden told the New Musical Express that the band were “known to smash up pairs of maracas on stage”. He was fuelling their image in aid of their first single release, consisting of I’m The Face (a reworking of Slim Harpo’s Got Love If You Want It) and Zoot Suit (based on The Showmen’s Country Fool and Misery by The Dynamics). Meaden told the paper the songs “accurately reflected the teenage lifestyle in such mod strongholds as the Goldhawk Club in London’s Shepherd’s Bush and Soho’s Scene Club”.

So how did a bunch of oiks from west London end up playing American R&B – and later, as The Who, remodelling it to their own ‘Maximum R&B’?

The answer lies, in part, a few miles away in Ealing, where Alexis Korner started the UK’s first R&B club, two years earlier in 1962. Not only did Korner’s band, Blues Incorporated, feature a host of musicians who later formed the bedrock of the British blues boom, they helped to popularise blues and R&B to the point where they usurped trad jazz as the main club draw. In November that year, Jazz News reported that “Alexis Korner and Blues Incorporated have been Thursday residents at the Marquee in Oxford Street for some months… audiences now reach almost 700 souls nearly every session… jiving, twisting, raving, just listening.”

Another writer at the time estimated that, between mid-1963 and mid-1964, more than 280 trad-jazz clubs switched over partly or wholly to a R&B soundtrack. Or, as another observer put it, “The harmonica industry went berserk.”

Alexis Korner and Cyril Davies were introduced to the Ealing club by their singer Art Wood, a west Londoner. As Blues Incorporated outgrew the Marquee and wanted a club of their own, they went in search of new premises. Art knew of a drinking club near Ealing Broadway station called the Moist Hoist, and drove there on his motorbike, taking Korner and Davies with him in the double sidecar. The deal was sealed and the Ealing Saturday Club was born, becoming a hugely important venue for The Rolling Stones and many others.

After Blues Incorporated went their separate ways, Art Wood formed his own band, The Artwoods performing a mix of standards such as Big City and their own R&B-inspired numbers. They were soon adopted by the mods, to the extent that Decca put a target on the sleeve of the band’s 1966 album, Art Gallery. Though their recording career wasn’t successful in chart terms, they were an attraction on the live circuit, holding the record for attendance at the Eel Pie Club in Twickenham.

Another important venue was the 100 Club in Oxford Street. Formerly a jazz club, in 1964 it was taken over by the Horton family, who geared it enthusiastically towards R&B, giving The Artwoods a residency, booking The Kinks and bringing over American blues artists such as Sister Rosetta Tharpe and Howlin’ Wolf.

So apart from the gigging circuit, how else were the kids hearing rhythm & blues? It certainly wasn’t available on mainstream radio and TV, where Merseybeat, Susan Maughan and the Singing Nun still ruled the airwaves.

The sought-after records were arriving in the UK via key figures such as Guy Stevens, the Scene Club’s resident DJ and R&B expert. Richard Barnes, author of Mods!, the definitive history of the subculture, says: “Stevens had every record you could think of and for a small sum he would record them onto a tape for you.”

Not everyone could get hold of Stevens’ elite collection, and even the kids who were regulars at these clubs or hearing the records on their mate’s tapes couldn’t always afford pricey US imports. The urban mod’s relatively healthy weekly wage had to stretch to cover clothes, shoes and pills, too. It wasn’t long before savvier record labels picked up on this appetite for black American vinyl and fell over themselves to feed it.

In April 1963, Pye acquired the UK rights to the Chess catalogue and launched its red and yellow label Chicago R&B series, with albums from Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley, as well as singles from Sonny Boy Williamson, Howlin’ Wolf, Bo Diddley and Cyril Davies & His All Stars.

EMI followed suit a few months later, creating the Stateside imprint and releasing a trio of singles from Chicago’s Vee-Jay label – John Lee Hooker’s Boom Boom, Jimmy Reed’s Shame Shame Shame and Roscoe Gordon’s Just A Little Bit.

All these records, along with releases on Guy Stevens’ UK Sue label, provided a wealth of material for the sets of every up-and-coming mod R&B band on the scene.

Salvation also came in the form of Ready Steady Go!, broadcast on TV from mid-’63 and bringing artists such as the Isley Brothers, Marvin Gaye and The Miracles into suburban living rooms every Friday teatime. A change had to come for blues itself and, on the fickle and fast-moving British music scene of the early 60s, the authentic Chicago style was on its way to becoming less fashionable than danceable R&B, early Motown and southern soul such as Booker T & The MGs.

One of the few bands to resist the pull away from blues, initially at least, were The Yardbirds, featuring mod god and blues obsessive Eric Clapton. Successors to the Stones’ residency at the Crawdaddy in Richmond, they’d started out, like many other fledgling bands, playing rock’n’roll until bassist Paul Samwell-Smith discovered Jimmy Reed’s Live At The Carnegie Hall, triggering their switch to blues. Sticklers for authenticity, The Yardbirds even recorded with artists such as harmonica player Sonny Boy Williamson. (Williamson was said to be less enamoured of his protégés, reportedly saying, “They want to play the blues so badly – and that’s how they play it: badly!”)

Over in east London, the blues was inspiring another out-and-out mod quartet, The Small Faces. Steve Marriott, the driving force of the band, was already an aficionado of the blues, soul and R&B. His first band, The Moments, had supported UK R&B pioneers Georgie Fame, Zoot Money and Graham Bond, all of whom galvanised Marriott to take his new band the Small Faces in the same direction. “American R&B music forcefully reflected his own inner passions and fires,” John Hellier and Paolo Hewitt write in their Marriott biography, All Too Beautiful. “It moved him like nothing else and soon he would seek to replicate the very same emotions that musicians such as Bobby Bland and Ray Charles had infused their work with.”

Marriott was another regular at the mod clubs. Come every Friday and Saturday night at 11.30pm, he would be part of the queue stretching down Soho’s Wardour Street to hear Georgie Fame & The Blue Flames play some of the hottest R&B in town. Coincidentally, Ian Samwell, who recorded Fame’s 1964 Rhythm And Blues At The Flamingo album, also co-wrote The Small Faces’ first hit, Watcha Gonna Do About It.

The Small Faces usually opened their set with You Need Lovin’, their take on Willie Dixon’s You Need Love, and the song ended up on their 1966 debut album, alongside a version of Sam Cooke’s Shake.

The first of the bands from London’s mod R&B enclave to have a hit record were The Kinks. On the advice of Alexis Korner, singer and songwriter Ray Davies had briefly been a member of the Dave Hunt Rhythm & Blues band, the first resident group at Yardbirds manager Giorgio Gomelsky’s Crawdaddy club in Richmond. The self-titled first Kinks album included covers of Chuck Berry’s Delilah and Bo Diddley’s Cadillac, as well as self-penned harmonica instrumental Revenge. The Kinks were less convincing exponents of R&B than the Stones, but Ray Davies went on to write his own observational style of London blues, albeit from a Muswell Hill perspective.

Although most of the musical activity centred on London, the influence of R&B reached to other British cities, which produced equally outstanding bands of the period, including Birmingham’s Spencer Davis Group, Belfast boys Them and The Animals from Newcastle.

Rhythm & blues provided the leading lights of the mod scene with the raw energy and inspiration for their own songwriting and creative ideas, and its impact can’t be overstated.

By 1965, The Who, The Small Faces and the Kinks were all regulars in the Top 10. That year, the National Jazz Festival, held at Richmond Athletic Ground, featured The Yardbirds, The Who, Manfred Mann, Graham Bond, Georgie Fame, The Animals and Steampacket (with Rod Stewart, Julie Driscoll and Long John Baldry). The R&B takeover was complete.