On a crisp October day in Birmingham, the Punk Beatles are drinking their way through a jet-lag hangover. Freshly fired up by a string of festival shows in the US, Buzzcocks are back on home turf to remind British audiences of their unique four-decade legacy, which stretches from the Sex Pistols and Joy Division to Nirvana, Pearl Jam and beyond.

Manchester’s subversively sweet bubblegum punk-pop pioneers may be known best for their glorious run of chart hits in the late 70s, but they are now 25 years into their second act, making them one of the last original punk bands standing. Even though they have just released their first album in eight years, The Way, Buzzcocks have been going steady for decades.

“We’re touring every year,” insists singer, guitarist and band co-founder Pete Shelley, now 59 and sporting a snowy Santa Claus beard. “It’s just that if you don’t make a record, people think you’ve died. On the internet it says we’ve re-formed many times. No! We split up in eighty-one, but we’ve been constant since eighty-nine.”

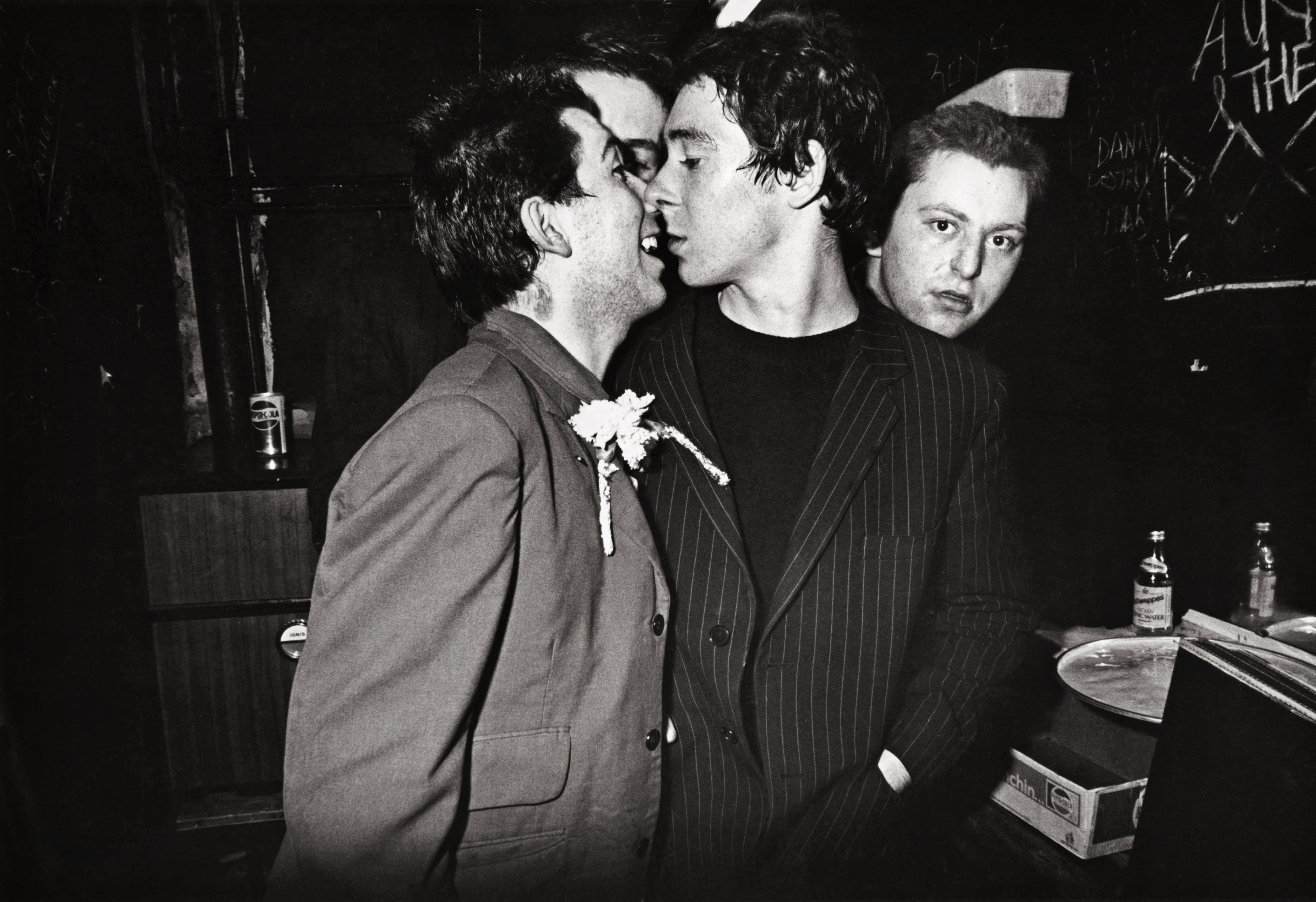

It’s mid-afternoon and Shelley is halfway through his second bottle of red wine. His long-time musical partner Steve Diggle, meanwhile, is sticking to lager. In a few hours, Buzzcocks are due on stage at the nearby Birmingham Institute.

Life on the road, says Diggle, used to be a riot of sex, drugs and debauchery to rival Led Zeppelin in their swashbuckling prime. But today these punky elder statesmen need to pace themselves a little more carefully. Between boozing and playing, they plan on grabbing a pre-show power nap.

“Me and Pete still have a drink or two,” says Diggle, as he knocks back his third pint. “There is still a lot of physicality on stage, the delivery is still as intense as it ever was. Unfortunately we’ve got to preserve our energy more nowadays.”

An exhilarating twin-guitar blast of amplified heartbreak and thrusting power-pop modernism, The Way is vintage Buzzcocks, the kind of vividly melodic, high-velocity racket that never gets old. Shelley and Diggle composed half the songs each.

As ever, Diggle leans towards ear‑bashing numbers like the jagged, powerhouse riff-chugger_ People Are Strange Machines_, channelling his inner Pete Townshend. “Well, you eventually become who you are, you know?” he says, grinning. “That’s not a conscious thing, it’s just the way I approach the guitar. I don’t think anything about The Who when I play.”

Elsewhere on the album, Shelley once again dips into his inexhaustible well of romantic despair, notably on the torrid confessional It’s Not You, possibly the finest adolescent angst anthem ever written by a man on the cusp of 60. “Some of it is hammed up,” Shelley admits of his melodramatic lyrics, “but it is something my younger self would probably have thought. I’m a lot happier now.”

Breaking new ground for Buzzcocks, The Way was pre-funded by online fan donations. Which is either a damning indictment of the contemporary music business or an inspirational punk statement. Maybe a bit of both. Tellingly, it’s the band’s first DIY indie release since their seminal four-track debut, the fabled Spiral Scratch EP, back in January 1977.

Shelley and Diggle insist that taking back control of their creative output was liberating after years of haggling with sclerotic, myopic record labels that could only see Buzzcocks as a ‘heritage’ act, stating they aren’t ready for the nostalgia circuit yet.

“We’ve both got girlfriends twenty years younger than us, that’s why it doesn’t fucking matter,” Diggle argues. “They still study Shakespeare at school, and he’s a lot older than us! We’re fucking One Direction compared to Shakespeare.”

Buzzcocks came to music as self-taught working-class intellectuals – or “punks with library cards”, in Diggle’s words. Shelley, born in Leigh, a mill town closer to Wigan than to Manchester, still talks with the rounded burr of a Lancashire native. Almost 30 years in London and two in the Estonian capital Tallinn, where he now lives with his Canadian-Estonian artist wife Greta, have not blunted his northern vowels.

By contrast, Diggle’s more urban South Manchester accent has been lightly cockneyfied by 20 years in London, making him sound like an odd mix of John Cooper Clarke and Ronnie Wood. Diggle grew up in Rusholme and Bradford, close to where Moors murderers Ian Brady and Myra Hindley preyed on their child victims. He still has flashbacks to a creepy encounter in late 1963.

“I remember two people trying to entice me and my cousins to come and sit down with them,” Diggle says. “Myra Hindley lived up the road in Gorton. It took me years to remember, but I can visually remember this Teddy Boy and this blonde woman saying: ‘Come and sit here.’ In fact if my cousins hadn’t been there I would have gone.”

Early exposure to Dylan and The Beatles, played to him by a beautiful 16-year-old neighbour, set Diggle’s teenage mind ablaze. Like Shelley, he became a kitchen-sink romantic, daydreaming of escape through art, music and poetry. “In those terraced streets you couldn’t see the moon, so that made you go internal,” Diggle recalls. “You become very aware of yourself, very philosophical in some way. It was a desert of the imagination. There was a lot of pain and emotion in those streets, which inspired me to write what I write about.”

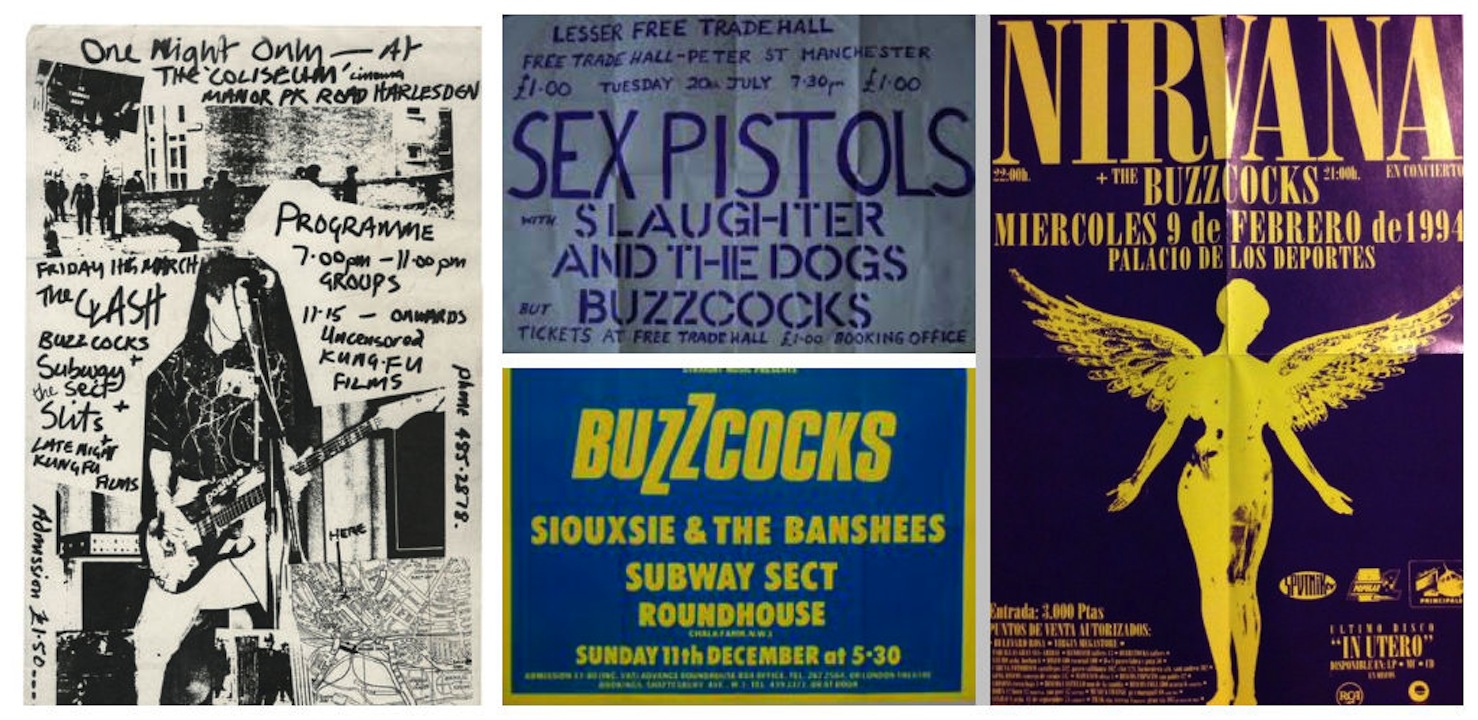

Famously, it was Shelley and fellow Buzzcocks co-founder Howard Devoto who booked the Sex Pistols to play two historic shows at Manchester’s Lesser Free Trade Hall in 1976, the second of which marked their own live debut. “The Sex Pistols kicked the doors open for everybody,” says Diggle. “They were the spearhead, really. It’s amazing they never developed into anything else, but they are a monument to that moment in time.”

Diggle was actually recruited to join Buzzcocks at the first Pistols gig, by accident. He had an appointment to meet another aspiring bandmate, but Malcolm McLaren introduced him to Shelley and Devoto instead. At first he played bass, but switched to guitar when Devoto left a few months later to form Magazine. Fondly recalling a pre-punk Manchester full of “seedy little clubs where ideas grew”, Diggle points out that Buzzcocks founded their own indie label and hosted their own club nights long before Factory and the Hacienda. “Tony Wilson came to see us and he just joined the dots,” he says. “We kick-started Manchester with all that.”

Signing to major label United Artists on August 16, 1977 (the day Elvis Presley died), Buzzcocks brought a poppy, irreverent sensibility to the post-punk charts. Their initial blaze of now classic singles included the BBC-banned _Orgasm Addict, plus evergreen teen-angst anthems like Promises_, What Do I Get?, _Everybody’s Happy Nowadays _and Ever Fallen In Love With Someone (You Shouldn’t’ve).

The openly bisexual Shelley’s lyrics of thwarted passion and unrequited love were always gender-neutral, a smart piece of ambiguity that clearly left an impression on Morrissey and Bob Mould. While Shelley never felt like a spokesperson for sexual equality, his frequent presence on Top Of The Pops was a quietly revolutionary statement. “I was never part of any community,” Shelley shrugs. “Being bisexual, you’re not really seen as being part of the gay community. But you were allowed to be yourself in punk. A lot of the clubs that would let you in if you dressed a bit differently were the gay clubs. You couldn’t go into the normal bars.”

Behind their instantly infectious melodies, there was an arty hinterland to Buzzcocks. Harmony In My Head featured impressionistic lyrics inspired by James Joyce, while A Different Kind Of Tension name-checked William Burroughs. Even during our interview, Shelley and Diggle quote Kant, Yeats, Montaigne and others. At their peak, Buzzcocks balanced literary pretensions with super-catchy three-minute songs about wanking.

“There’s very little about wanking,” Shelley protests. “Only one-and-a-half songs! The main one was Palm Of Your Hand. But these things are part of the human condition. All artists have to hold up the mirror like that.”

On first impressions, the Wallace and Gromit of punk-pop make an odd couple. Shelley writes sensitive love songs with a confessional, vulnerable edge, Diggle favours socio-political tirades and stream-of-conscious screeds.

The former is full of soft-spoken mirth and mischief, the latter is wired and bullish. Shelley seems to have stepped out of an Alan Bennett play, Diggle out of Quadrophenia. “We’re polar opposites, but at the same time it crosses over,” Diggle says. “He’s a bit more first-person, I’m a bit more third-person. I just put the proposition forward with a bit more complexity. But we’re not like The Who – they punched each other. We haven’t got that far yet.”

Shelly characterises his relationship to Diggle more in terms of “sibling rivalry” than marital tension. “I tend to be very analytical, and Steve tends to be Mr Rock’n’Roll, but the two sides complement each other,” he explains. “Sometimes people read too much tension and dichotomy into it, like hammer and tongs. But hammer and tongs both work together, don’t they?”

Even so, there have been fall-outs over the years, notably when Shelley quit to launch a solo career with his 1981 album Homosapien. This came as news to Diggle, who was working on tracks for a fourth Buzzcocks album at the time. “It took a while before we spoke to each other again,” Shelley admits. “I think he was more upset that I was. Ha!”

Diggle spent most of the 1980s fronting the Buzzcocks spin-off band Flag Of Convenience, but he eventually reconciled with Shelley. Having reunited in 1989, they have since worked with a parade of temporary members including Manc-rock legends Mike Joyce and Barry Adamson. The current rhythm section of drummer Danny Farrant and bassist Chris Remington have been in place for almost a decade. “I’m the only member that’s never left the Buzzcocks,” Diggle says. “Every other member has actually left. But, ironically, they’ve all come back, one way or another.”

Buzzcocks have left an enduring impression on rock history, from their origins as northern punk scene-leaders to their evergreen gravitational pull on several generations of grunge, emo and pop-punk bands. Yet they never quite achieved the status of former contemporaries like The Clash or the Pistols. “I think that’s partly because they were from London,” Diggle muses. “And they were a little bit more showbiz. We were more internal, singing about the human condition. Also, we did a lot more than just linear pop songs, like Autonomy, Fiction Romance, and the Can-influenced things. The first Pistols and Clash albums were a lot more straightforward.”

Shelley is more succinct. “They come from pub rock, we come from art rock. Anyway, we’re still playing and we’ve done more albums.”

In the US, Buzzcocks arguably have had an even bigger influence than at home, inspiring generations of post-punk and melodic hardcore acts, from Hüsker Dü to Pearl Jam, Green Day to The Offspring. “People keep their cards close to their chest here,” Shelley shrugs, “whereas in America we’re exotic so it’s okay to drop our name.”

Shelley says he tries not to worry about all the bands that copied the Buzzcocks’ formula and turned it into stadium-filling riches. “Every time we play festivals in America, the side of the stage will be full of all these bands who have sold zillions of records, and I’ve no idea who they are!”

Nirvana were just one of these zillion-sellers, and invited Buzzcocks to open for them on their final European tour in February 1994, just weeks before Kurt Cobain’s suicide. “They had fantastic catering,” Shelley sighs. “We would be in their dressing room, eating their shrimps.”

Neither Diggle nor Shelley remember Cobain seeming depressed. “We spoke about guns,” Diggle recalls, “but he was a very lovely, sensitive guy caught in the middle of this stadium thing. We’d walk around the stadium, and he asked how we had survived. I enjoyed his intensity. He was trying to figure himself out in a lot of ways.”

Several of Nirvana’s grunge-era contemporaries are also Buzzcocks fans. Long before Pearl Jam, Eddie Vedder would chaperone Diggle around guitar shops in LA and Seattle. Fast-forward to 2003, and Pearl Jam invited Buzzcocks to tour with them. Vedder even brought Diggle on stage at Madison Square Garden to play The Who’s Baba O’Riley on Johnny Ramone’s guitar. Yet Diggle seems mildly aggrieved that Buzzcocks never reaped the same rewards as some of their acolytes. “Van Gogh did a lot of painting, he never got paid for it,” he sighs.

Shelley is more philosophical. “It depends if you believe in Kant’s proof that there must be a heaven,” he says. “Because you definitely don’t get what you deserve down here.”

“That’s always been the case,” Diggle adds. “The inventors of things never get the rewards that the people who come after get. Remember, when Radio Piccadilly in Manchester first played Spiral Scratch, they threw it across the room and said: ‘We won’t be playing that rubbish again.’ But when we go back to Manchester now we’re treated like kings. Even a whore becomes respectable in the end.”

Once Buzzcocks were young punks with library cards. Soon they’ll be old punks with bus passes. Is it possible to keep the flame alive into middle age? Shelley thinks it is. Punk was never about “gobbing and sneering”, he argues, it was about liberation. “The main thing is the attitude,” he says. “Punk wasn’t a way to advance your musical career, not then. But you did it and a musical career came out of it. It came as a shock that what was anti-music struck a chord – or struck a discord – and became a popular art form. It became the vibrant kick up the arse that is still missing now. The only thing that’s stopping you achieving your dream is thinking you could never do that.”

The Way is out now.

_ _