Whether with prog-jazz pioneers Soft Machine or on his own dreamlike solo albums, Robert Wyatt always followed his instincts – right up to feeling it was time to retire in 2014. The following year he offered Prog an overview of his remarkable achievements.

“The music I heard in my head didn’t really exist in the real world,” says Robert Wyatt, trying to explain the unique otherness of his recorded work. “Elements of my ideas were already out there – an attraction to hummable tunes, for example – so I was neither trying to be different, nor trying to sound familiar. I’m not interested in following a tradition; but nor am I interested in being esoteric. I just follow my undirected instinct wherever it leads me.”

Wyatt’s instinct has rarely let him down. In a career that he brought to an unexpected close in 2014 with his retirement from music, he produced some of the most strikingly original work of the past half century. His, he says, is “an improvised life” – one fuelled by jazz, socialism and an absurdist slant on the world around him.

It’s an approach that first found expression with prog-jazz pioneers Soft Machine n the mid-60s, though he’s keen to dismiss the notion that they were part of a broader Canterbury Scene. “There were a few musicians I played with from around there, but I don’t remember a ‘scene,’” he says, explaining that he feels, Canterbury was more emblematic of a very English variant on freeform jazz and psychedelia.

Referring to their countercultural days at London’s Roundhouse and UFO Club, Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason described the Softs and his own group as “the twin house bands of the London underground.” Wyatt reflects: “I always found the underground a more realistic place to be. There’d be bodies all over the floor, film projections on various surfaces, and a right old racket coming from the stage. There was a timeless feel, altogether rather dreamlike.”

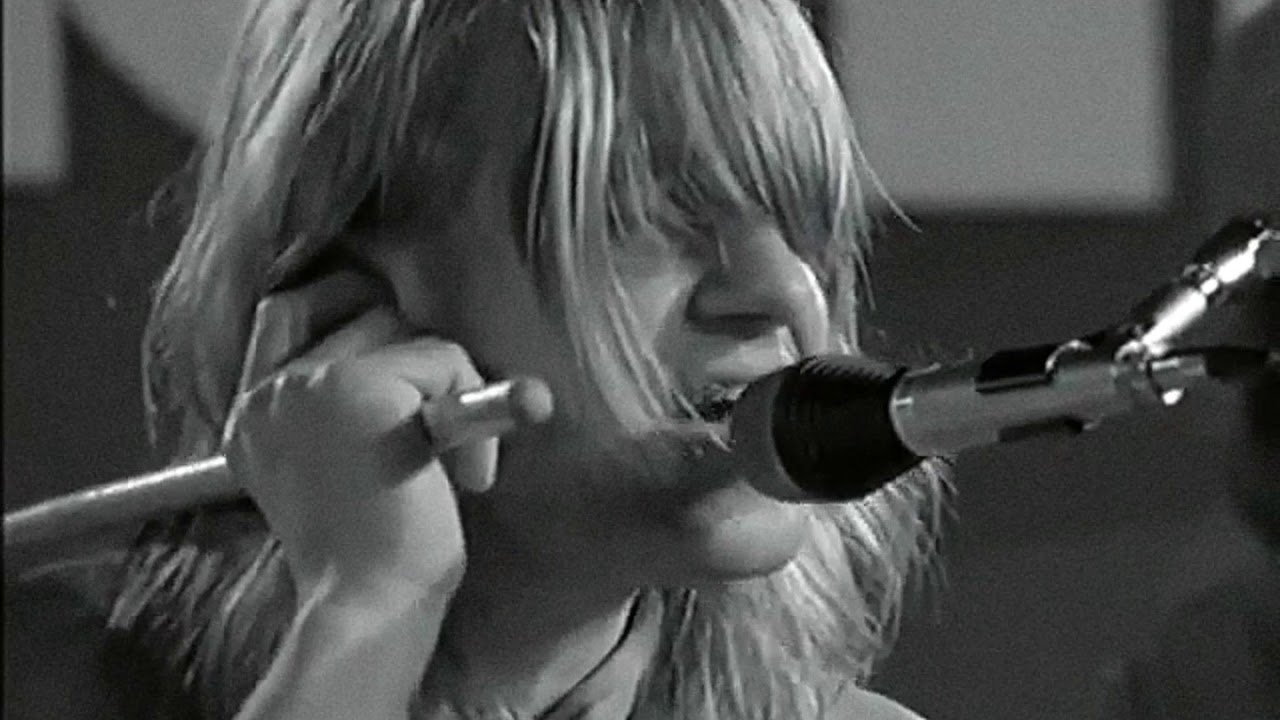

Wyatt’s memories as singer/drummer of Soft Machine – for whom he contributed such stellar moments as Moon In June – are bittersweet. By his own admission, he’d become a liability by the time of 1971’s Fourth. An obstinate boozer and wild stage presence (flailing, shirtless, from behind his kit), he was utterly at odds with the restrained disposition of bassist Hugh Hopper and keyboardist Mike Ratledge. In autumn ’71, Wyatt quit to form Matching Mole – though, as Hopper admitted later, he was effectively “pushed out of what he felt was his own group.”

The episode forms one of the most moving passages in Marcus O’Dair’s book, Different Every Time: The Authorised Biography Of Robert Wyatt. In it, the subject confesses he still has nightmares about being ejected from the band. “It is strange, even to me,” he says. “Something to do with the humiliation of rejection, when it’s rejection from the people you got together with in the first place, I guess.”

Post-Soft Machine, two events changed him forever. In early 1972 he met artist Alfreda Benge, who was to become his wife, muse and lyricist. It also coincided with the beginning of his devotion to Communism, with politics serving as “the missing protein” in his music.

Then in 1973 came the drunken fall from a window that left him paralysed from the waist down. The effect, he says, was truly liberating, in that it narrowed his career choices and made him concentrate on being a singer. He calls the accident a neat dividing line between adolescence and the rest of his life: “Your youth is a period of maximum physical potential. Suddenly being anchored to a wheelchair forces you to experience life in a more abstract way. You become more reflective.”

Aside from his expressionistic blend of free jazz, folk, classical and world music, what truly sets him apart is his exquisite voice. Reedy and tremulous, there’s a haunted vulnerability and disarming candour to his singing, which his friend Brian Eno compares to “a poor innocent cast into a complicated world.”

I do like to rummage around what’s been done in the past and find a different take on it

There are very few precedents for Wyatt’s voice. “I try to make the most of what’s doable with it,” he says. But one chief inspiration was the late English tenor and Benjamin Britten collaborator Sir Peter Pears. “I didn’t warm to opera singing, but Peter Pears had a gentler vibrato, which suited Britten’s adaptations of folk songs in particular. They were probably the first records that got to me as a toddler.”

The sheer breadth of Wyatt’s solo work is dizzying. As an extension of his modus operandi – “I do like to rummage around what’s been done in the past and find a different take on it” – he has reworked pieces by such disparate artists as John Cage and The Monkees, and recorded with Henry Cow, Eno, Phil Manzanera, Syd Barrett, Björk and Ryuichi Sakamoto, to name but a few.

“I think of it as alternating dictatorships,” he says of his myriad collaborations. “On my records, I hope the musicians I invite will trust me to put it all together in my own way. Conversely, when employed by others, I try to do what they would like me to do.”

Stick a pin anywhere you like, from 1974’s Rock Bottom to 2007’s Comicopera, from Soft Machine’s 1968 debut to 2010’s For The Ghosts Within, his three-way alliance with Gilad Atzmon and Ros Stephen – all of these albums are freighted with his rare brilliance. For all the genre-hopping, his work occupies a distinct corner entirely of its own.

“My identity doesn’t feel threatened by cultural variety,” he says. “Such differences as there are seem to me to highlight the specialness of each. Underneath, what we have in common with others warms the heart even more. My heart, anyway.”