Funny thing, geography. You might think it’s all neatly mapped out these days, but go in search of ‘Canterbury’ and you might be surprised where you end up. Punching up the Sat Nav will get you from A to B without much bother, but ask a music fan to define where Canterbury begins and ends and there’s a strong chance you’ll end up getting confused or lost. Or both. The borders of the Canterbury Scene can be frustratingly porous and subject to the vagaries of taste and opinion.

If you wanted proof of how wide that musical map can be drawn then consider this list: Soft Machine, Caravan, Kevin Ayers, Bruford, Egg, Hatfield And The North, National Health, Rapid Eye Movement (basically anything with keyboard player Dave Stewart in the line-up), Henry Cow, Khan, Soft Heap, Gong, Slapp Happy, In Cahoots, Mike Oldfield, Camel, Gilgamesh, Matching Mole, Quiet Sun and numerous others have all been referred to as Canterbury Scene contenders.

And what of groups beyond the UK who are regularly co-opted into this generic description? Supersister, D.F.A, Moving Gelatine Plates, Picchio Dal Pozzo, Alco Frisbass, Forgas Band Phenomena? Other groups that are sometimes said to contain something of the Canterbury DNA in their work include Ultramarine, Sanguine Hum, MIRthkon, Schnauser, Henry Fool and… well you can see the problem.

Aymeric Leroy, founder of the encyclopaedic website Calyx and its long-running newsgroup What’s Rattlin’, both dedicated to the subject, reckons the term as generic description was coined by Melody Maker journalist Steve Lake in 1973. Leroy, who is to publish Legends In Their Own Lunchtime, the first of two volumes covering the scene’s history later this year, offers this definition of what constitutes a generic Canterbury band: “For me it’s the cohabitation between extremes; one minute goofy, next cerebral, the next pop. On the one hand you’ve got very complex, weird ideas and on the other, very accessible music that’s often melodic and lyrical.”

Which artists included in this subset of progressive music would he say don’t really belong? “Occasionally, Henry Cow verged on the Canterbury territory, clearly influenced by Soft Machine when they started out, and on [1973’s] Legend it’s still there. [Henry Cow’s guitarist] Fred Frith was influenced by [Hatfield And The North’s] Phil Miller’s playing style at the time but they grew into their own thing. Then there’s Camel. I like them but apart from Richard Sinclair’s membership of the group for a while, there’s nothing Canterbury about them. They’re really a symphonic prog rock band.”

Dave Stewart, whose keyboards and compositions have graced albums by many of the outfits mentioned in this article, has no confusion about who or what is and isn’t Canterbury: “There was a simple reality to it at the time which was that in the late 60s a couple of exceptional bands emerged from Canterbury – Soft Machine and Caravan.”

Caravan’s guitarist Pye Hastings moved from Tomintoul in the Grampian mountains to Canterbury at the age of nine. As a teenager he joined The Wilde Flowers, an R&B combo that began in 1964, the brainchild of brothers Hugh and Brian Hopper, and whose line-up at various points included Robert Wyatt, Kevin Ayers, Richard Coughlan and Richard and Dave Sinclair.

“Canterbury in the 60s was a country town very much in the ‘Conservative/Cathedral City’ mould,” recalls Hastings. “Mostly we were tolerated by the older generation but certain old fuddy duddies were very anti any change to the status quo and would go out of their way to let you know. Hugh Hopper was memorably barred from a local pub just for the way he looked. It was featured in the local newspaper and of course we all thought of him as a bit of a hero for it.”

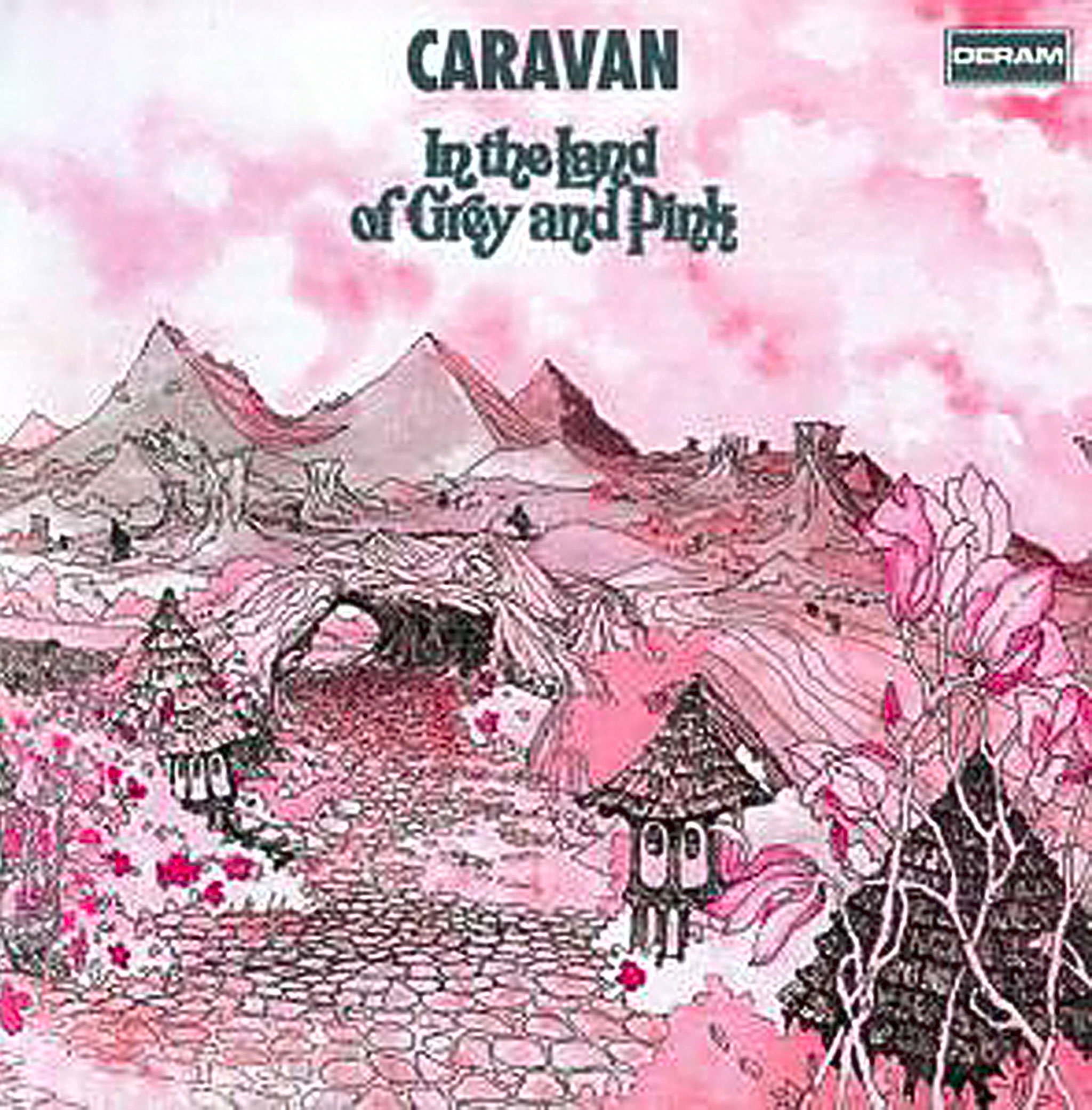

With their journey from psychedelic pop to jazzier experimentalism, embodied by 1970’s Third album, Soft Machine might be said to be the head of the Canterbury Scene. If that’s so then there’s a strong case to be made that Caravan are the heart of the scene. “I like that,” says Hastings. “To this day I am still trying to write that most elusive thing, the simplest of melodies that will connect with the most number of people. That only comes from the heart, so if I achieve that then I will have succeeded. I would say that Nine Feet Underground from 1971’s In The Land Of Grey And Pink, written by Dave Sinclair, would most likely be the one track which would be chosen by the fans as having all the ingredients representative of what is called the Canterbury Sound. Six different sections joined together to make one piece which really demonstrates what a great writer and a stunning and unique Hammond Organ player he is.”

Elsewhere, the album’s title track contains a prime example of the genre’s frequent bittersweet quality. Aside from the playful lyrics, it contains a gently descending piano solo, like cathedral bells heard from a distance. The organ solo that follows is a sunlit echo, brimming with giddy optimism. That air of happy expectation was something future vocalist Barbara Gaskin encountered, along with Caravan themselves, when she arrived at Canterbury university in 1969.

“We lived in a communal house in St. Radigunds Street which was a real hive of creative activity,” she says now. “My experience of the city was by the university which was up on a hill a modern university where you looked down from some of the colleges and saw the cathedral in the valley. Very beautiful. Caravan were gigging and we introduced ourselves to them. They were the band back then. They’d been on Top Of The Pops which meant as far as we were concerned they’d made it! When I first arrived there I met Steve Hillage immediately. He’d been in Uriel and he introduced me to Dave Stewart who lived in London but often visited.”

Gaskin wasted no time plugging into the music scene within the college and joined psych-folk outfit Spirogyra. At the end of her first year she took a sabbatical to concentrate on being in the band full time. Appearing on all three Spyrogyra albums, including their 1971 debut St. Radigunds and the 1973 cult classic Bells, Boots And Shambles, Gaskin also performed on Hatfield And The North’s debut and did a few gigs with them as a member of backing vocalists The Northettes.

Despite their obvious geographical connection, Gaskin rules out Spirogyra as belonging to the Canterbury Scene. “Caravan and Spirogyra were very different musically. At that time there was no such thing as the generic Canterbury scene – there were just bands in Canterbury.”

Steve Hillage, whose Canterbury credentials include Uriel’s Arzachel, Khan’s Space Shanty and his solo debut Fish Rising, was in Canterbury from 1969 to 1971. “There was a definite scene and style then, so I would say the concept of a ‘Canterbury Scene’ pre-dates 1973,” he states. “There was a network of musicians who knew each other and often played with each other – that is a historical fact. Gong still is a unique international phenomenon, but it’s a historical fact that we were strongly intertwined with Canterbury, in particular through Daevid Allen being a founder member of Soft Machine. Kevin Ayers played with Gong for a period and had close links with the band. Pip Pyle was one of Gong’s legendary drummers. I had links with Pip and with Kevin before joining Gong. Robert Wyatt played on Daevid’s Banana Moon album, and there’s a certain quirkiness and whimsy in quite a few of Gong’s songs that you could say is very much connected to the Canterbury style. In fact, you could say that Gong were the ‘bad boys’ of the Canterbury Scene.

“Certainly, labels can be a problem. though,” he continues, “because as music creators we all have our own creative personalities, and we prefer to be appreciated for what we do as individuals rather than as part of a ‘scene’. But the so-called Canterbury Scene definitely had a wonderful and unique musical style and I’m happy to be associated with it.”

If one band can be said to be tailormade for Aymeric Leroy’s description of “one minute goofy, next cerebral, the next pop”, it would be Egg, who worked from 1968 until 1972.

“We wanted to be too original for our own good,” observes Mont Campbell, Egg’s vocalist, bassist and principal composer, and later a member of National Health. Constantly adventurous, Egg moved fluently from the extremes of inordinately complex long-form pieces on The Polite Force (1971) to seditiously witty pop tunes, such as their 1969 single, Seven Is A Jolly Good Time.

“I couldn’t have been populist to save my life, still can’t,” states Campbell. “How I’m still alive at all is something of a mystery! As a composer I was excited by musical complexity and fondly imagined that others would be too. Seven Is A Jolly Good Time is self-mocking and an attempt at being jokey but not populist enough for a single. The B-side, You Are All Princes, is one of the best songs I ever wrote and the harpsichord improv is one of Dave Stewart’s most impressive pieces of work. His improvisational genius was the real gem of the band, and it is that which has stood the test of time.

“I have spent the last 40 years feeling mostly embarrassed about my prog rock days,” he admits. “But I’m starting to realise that’s not quite justified. The music wasn’t popular but it doesn’t matter. Some of it was very good. How do you define good music? I think you can only answer that question with the test of time. Are people still discovering it and valuing it 40 years later? If they are then it was all worth it.”

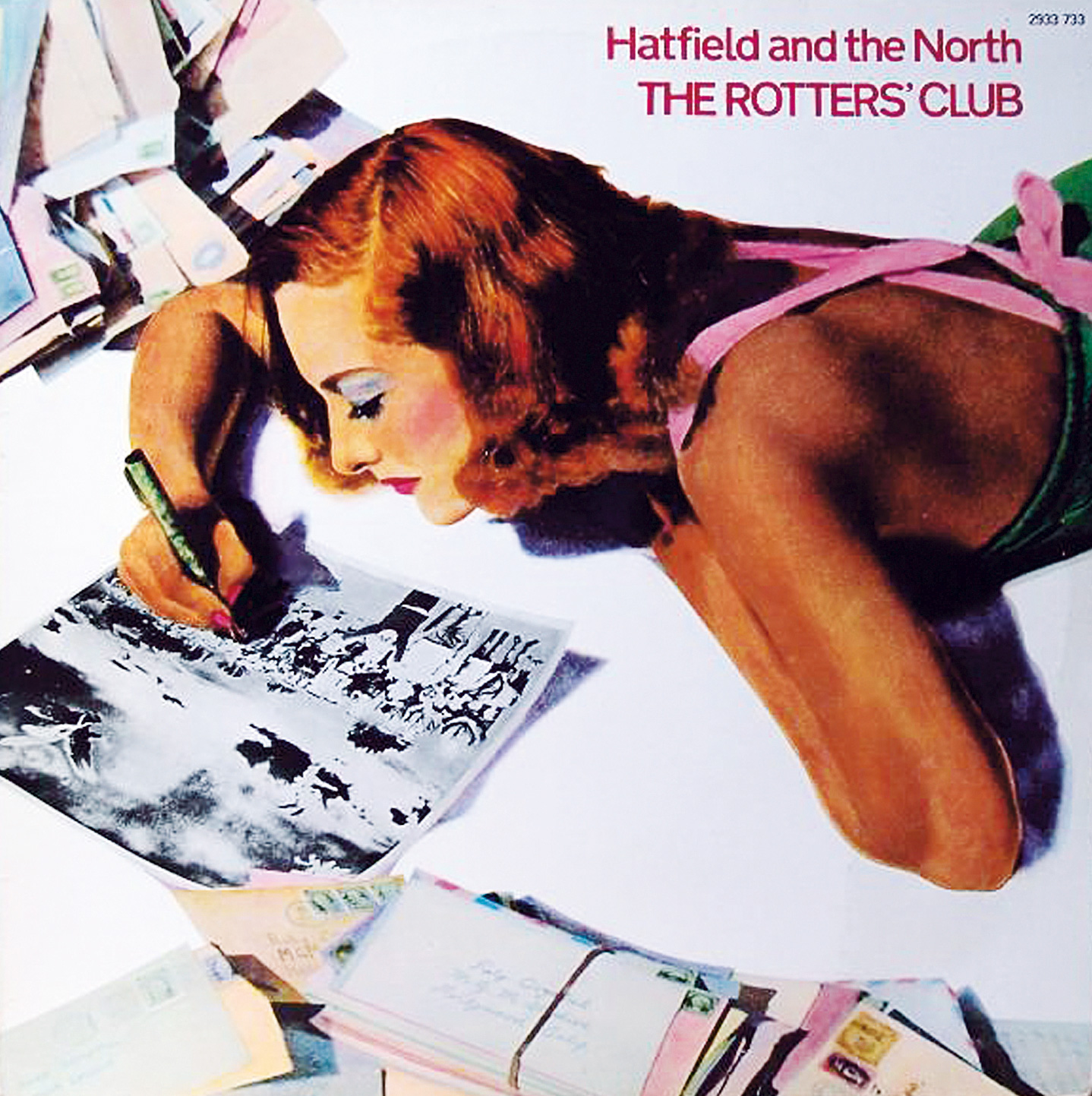

Guitarist Phil Miller has played with Delivery, Matching Mole, National Health and In Cahoots. However, it’s his tenure with Hatfield And The North which is most fondly remembered. Their only studio albums, 1974’s self-titled debut and ’75’s The Rotters’ Club, are routinely touted as high points of the Canterbury Sound genre, as is a feeling that the group’s full creative potential was never quite realised.

“I think we probably did somewhere in the region of 100,000 sales for both albums all told which is a hell of figure,” says Miller. “The band was well thought of and could have potentially been quite popular, but it didn’t last long enough to do that. Bands have a finite length, a certain number of hours together before you get on each others tits.

“You know what music is,” he adds. “It brings out the best and worst in people. We were just starting to make decent money and the gig sheets were looking good for next year, and if Richard Branson or somebody from Virgin had come along and told us to pull ourselves together that might have made a difference. But it couldn’t be done. My abiding memory of that period was mostly good though.”

Is it at all irksome to see his current band In Cahoots categorised next to something he did nearly 40 years ago? “It’s obviously a construct that people like to use to group us together. It’s a bit artificial although I use it myself, just because it helps some people understand roughly the area that the music is in.”

While all of this is history, what of the bands based in the city today? Do they see any link to Canterbury’s musical past? Syd Arthur, whose 2014 album Sound Mirror artfully merged psychedelic and progressive music sensibilities, are not only aware the sense of lineage, but have earned an endorsement from some older- generation Canterbury players.

“Our violinist Raven Bush knew Hugh Hopper, and we’ve spent time with his brother, Brian, who also used to be in The Wilde Flowers,” explains Syd Arthur bassist Joel Magill. “Those guys are enthusiastic about what we’re up to. Brian says that musically we might be different, but as an ethos and a vibe, we’re doing what they were doing back then, which was trying to bring in new sounds and influences.”

Those influences have a habit of turning up in the unlikeliest of places. The viewers and judges of the BBC TV talent show The Voice were recently wowed by the energetic duo Billy Bottle And Martine’s rousing cover of Snap’s 1990 dance hit The Power. Yet the thousands who subsequently followed the pair on Twitter might have a harder time getting to grips with Unrecorded Beam, Billy Bottle And The Multiple’s remarkable 2013 song cycle that cleverly refracts rock, folk and jazz through a prism of Canterbury pastoralism.

Bottle grew up listening to Kevin Ayers, and completed a dissertation at Surrey University in 2002 entitled ‘Part Of The Dance – The Impetus Behind The So-Called Canterbury Scene’.

“My lecturer was a big Caravan fan,” he explains. “I did a recital and that’s where The Multiple started.” Bottle has also toured and recorded with ex-Caravan keyboard player, Dave Sinclair. “I met Dave through a mutual friend while I was doing my dissertation and worked with him on his [2011] Stream album, out in Japan singing on a couple of numbers, playing bass, guitar, helping with arrangements and doing some co-production.”

Dave Sinclair, who’s lived in Japan since 2005, says the Canterbury spirit can be found in the most unlikely places. “For example, the very well-known Japanese band Clammbon recently recorded a dub reggae-type version of [Matching Mole’s] O Caroline on their latest album, which has resulted in me and [occasional Caravan woodwind player] Jimmy Hastings collaborating with them at the Billboard Live club in Tokyo this May.”

On his 2013 album, The Little Things, Sinclair presents a homage to his hometown in a song called Canterbury. With vocals by Billy Bottle, it’s a beautiful, stately tune saturated with a sense of times and friends long gone. Sinclair found inspiration while sitting at the top of St. Thomas’ Hill looking out over the mist shrouding the cathedral in the valley below.

“For a few minutes I wondered how the city would have been hundreds of years before, say in the time of Chaucer or Marlowe, and of the lives of the people who had lived there,” he says. “So I put it all into my song. Being my hometown it feels even more poignant now that I live so far away.”

The stylistic distance between those herded under the Canterbury banner is clearly a blessing for some and a curse for others. For Dave Stewart and Barbara Gaskin, who have released a series of albums whose music they describe as ‘intelligent pop’, not to mention bagging a No.1 hit single in 1981 with It’s My Party, that constant connection isn’t helpful.

“I left National Health in 1979 and that was the end of it for me,” says Stewart. “End of story. New worlds opened up and I progressed from where I’d been to where I am now.

“This is why we can’t play at a prog festival because they’ll say, ‘On the bill, Dave Stewart, ex-Egg’. Then people’ll say, ‘This isn’t fucking Egg! I want my money back!’ This is why it’s unhelpful for me to have to keep dealing with this label. I don’t want to pretend my musical heritage doesn’t exist, but there comes a point where it becomes counterproductive.”

There’s a scene in the movie Help! in which The Beatles pull up in a street, get out of their Rolls Royce and troop through the front doors of what from the outside looks like four separate terraced houses, but are, in fact, revealed to be one large impossibly cool open-plan home. The continued use of the label to some degree fosters that sense of connectedness, real or imagined, in which the Canterbury alumni are similarly corralled – communally drinking tea and playing riffs in 15⁄8. “That’s right!” laughs Stewart, “It’s like we’re all living in Number 14 Canterbury Street.”

Canterbury Around The World

How the music of a Kent cathedral town went global.

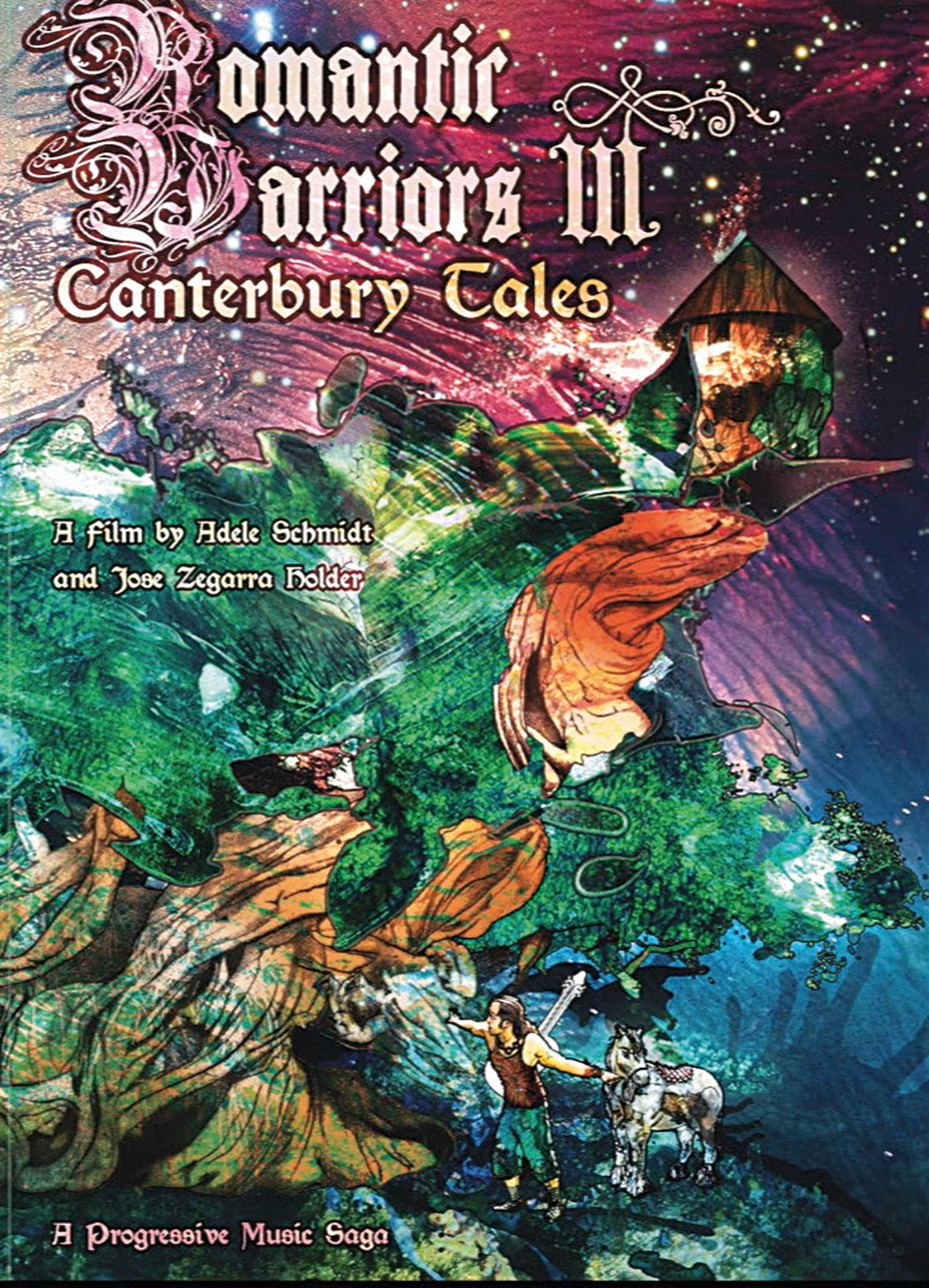

Film makers Adele Schmidt and José Zegarra Holder have spent several years documenting progressive rock via their documentary series Romantic Warriors – A Progressive Music Saga. The first two series covered the US east coast prog scene and the Rock In Opposition movement. The third, currently being edited, focuses on the Canterbury Scene’s past and present and explores its international offshoots. “Creating a documentary that reflects the complex history of the Canterbury Scene has been a wonderful journey inside a boundless world of music,” explain the couple. Schmidt and Holder think that the qualities that distinguish Canterbury music from other 1970s progressive music include playful lyrics sung in whimsical ways and the mix of jazz and psychedelic rhythms and melodies. They cite The Netherlands’ Supersister, France’s Moving Gelatine Plates and the US’ The Muffins and Happy The Man as keeping the flame burning during the 1970s. Today, bands such as Planeta Imaginario in Spain, France’s Forgas Band Phenomena and Belgium’s The Wrong Object have all been associated with the scene. Some admit being influenced by Soft Machine’s wah-wah organ/spaced-out keyboards and others by Caravan’s pastoral sounds. Some show the same American jazz influence that marked out later-era Soft Machine with Elton Dean’s soprano sax. Some incorporate Canterbury-like sounds but mix them with a myriad of other influences, ranging from regional music to Zappa-esque jazz-rock. Although it mirrors the same pattern of emergence, climax and decline that you’d find in the history of any of the progressive sub-genres covered so far, it’s a more closed, exclusive club of friends and collaborators than what we see elsewhere. Check out www.progdocs.com for more info about Romantic Warriors – A Progressive Music Saga.

Canterbury For Beginners

Five Canterbury Scene albums everyone should hear.

Soft Machine: Third (CBS, 1970)

Comprising four side-long jazz rock epics featuring Mike Ratledge’s frenetic organ playing, Elton Dean’s cathartic sax and Hugh Hopper’s savagely roaring fuzz-bass, this double album also contains drummer Robert Wyatt’s warped autobiographical-based song Moon In June, a poignant connection to a psychedelic past that finally unravelled after this 1970 classic…

Caravan: In The Land Of Grey And Pink (Deram, 1971)

Released in 1971, Caravan’s third album, housed in its baroque artwork, brims with pop/prog whimsy about drinking tea, meeting girls in PVC and memories of summers gone, all blessed with sunny optimism and Richard Sinclair’s rich vocals and cousin Dave’s winning fuzzed organ solos…

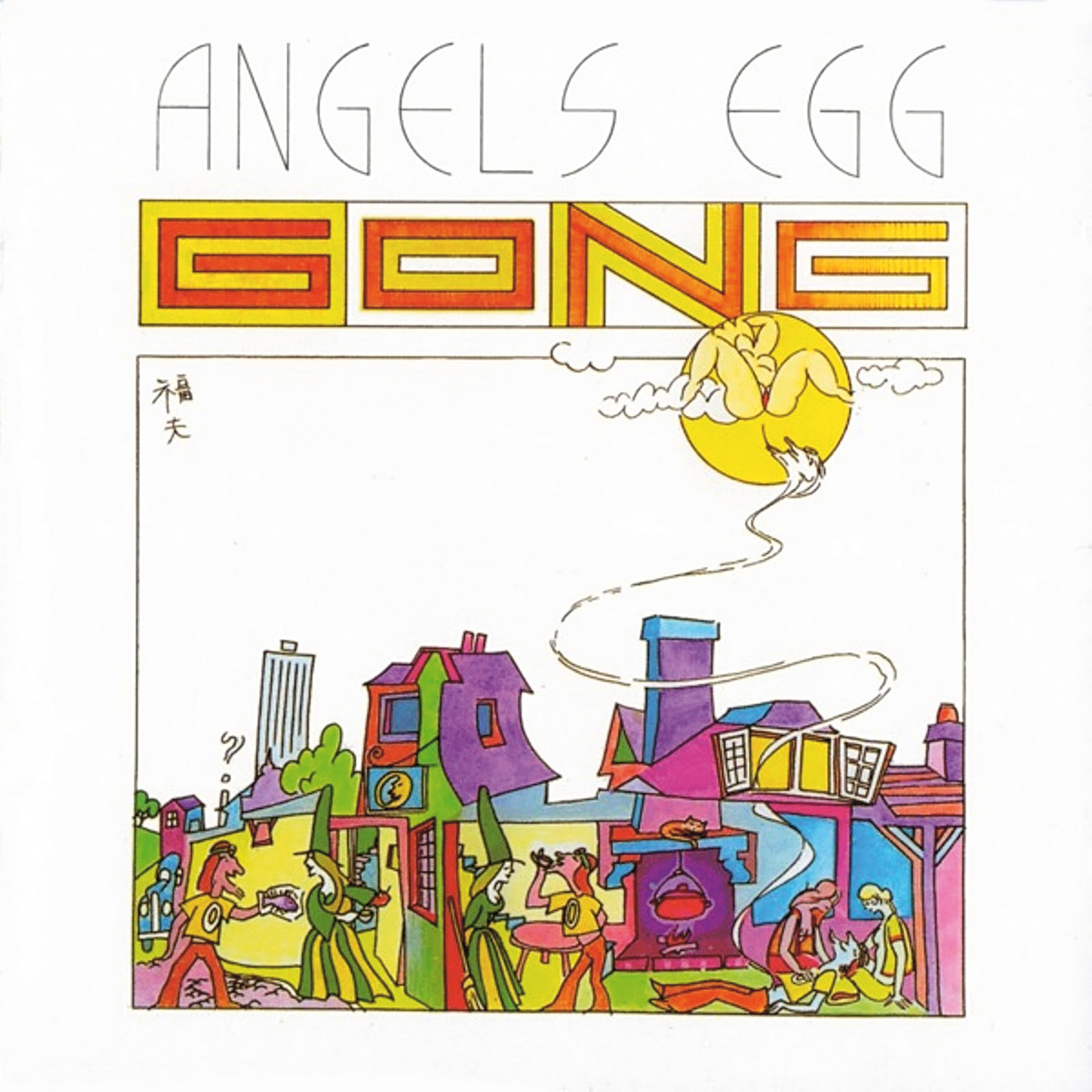

Gong: Angel’s Egg (Virgin, 1973)

The second instalment of Gong’s Radio Gnome trilogy finds Daevid Allen’s international collective hitting their stride. The trademark slapstick humour and allegorical wordplay are all present but now with the added attack of Pierre Moerlen’s drumming, Steve Hillage’s blissful bursts of heavenly guitar and a confidence that comes from knowing that nowhere is off limits.

Hatfield And The North: The Rotters’ Club (Virgin, 1975)

An inspired combination of fiendishly complex instrumentals such as the breezy jazz stylings of Underdub and the absurd laugh-out-loud singalong Fitter Stoke Has A Bath, this is a soundtrack for the head and heart. Phil Miller’s scorching guitar and Dave Stewart’s stirring keyboard themes are among the principal attractions that have ensured devotion for the past 40 years.

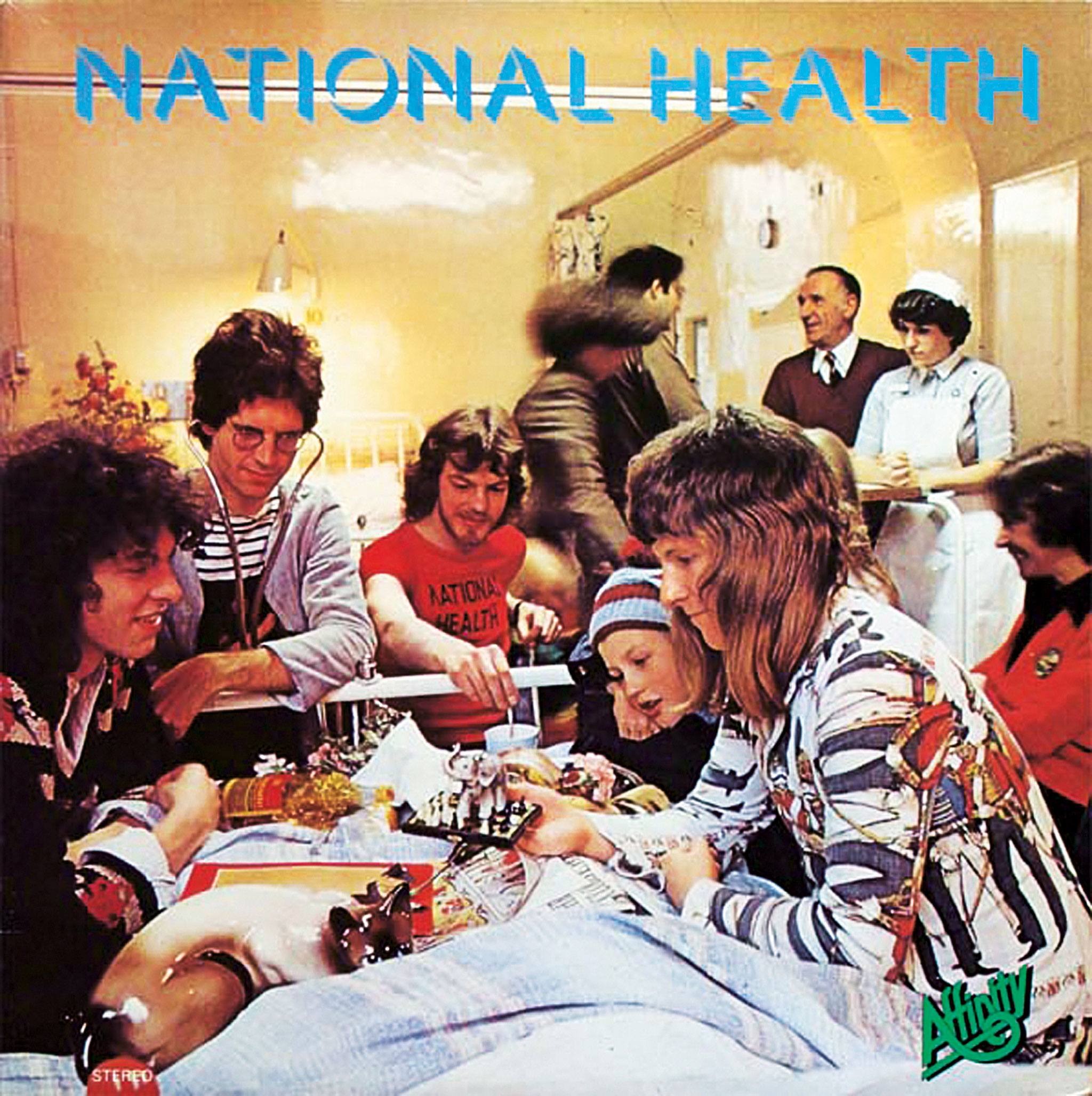

National Health: National Health (Affinity, 1977)

Led by Dave Stewart, National Health’s intricately woven compositions are performed as a kind of chamber music for a rock ensemble. Featuring Gilgamesh keyboard player Alan Gowen as well as Hatfield stalwarts Phil Miller and drummer Pip Pyle, with soaring lead vocals from ex-Northette Amanda Parsons, this 1975 album is an essential purchase for any Canterbury fan.