The death of Razzle: a story of Vince Neil and a car crash

On a US tour in late 84, Hanoi Rocks seemed poised for greatness. But then Vince Neil drove onto the scene

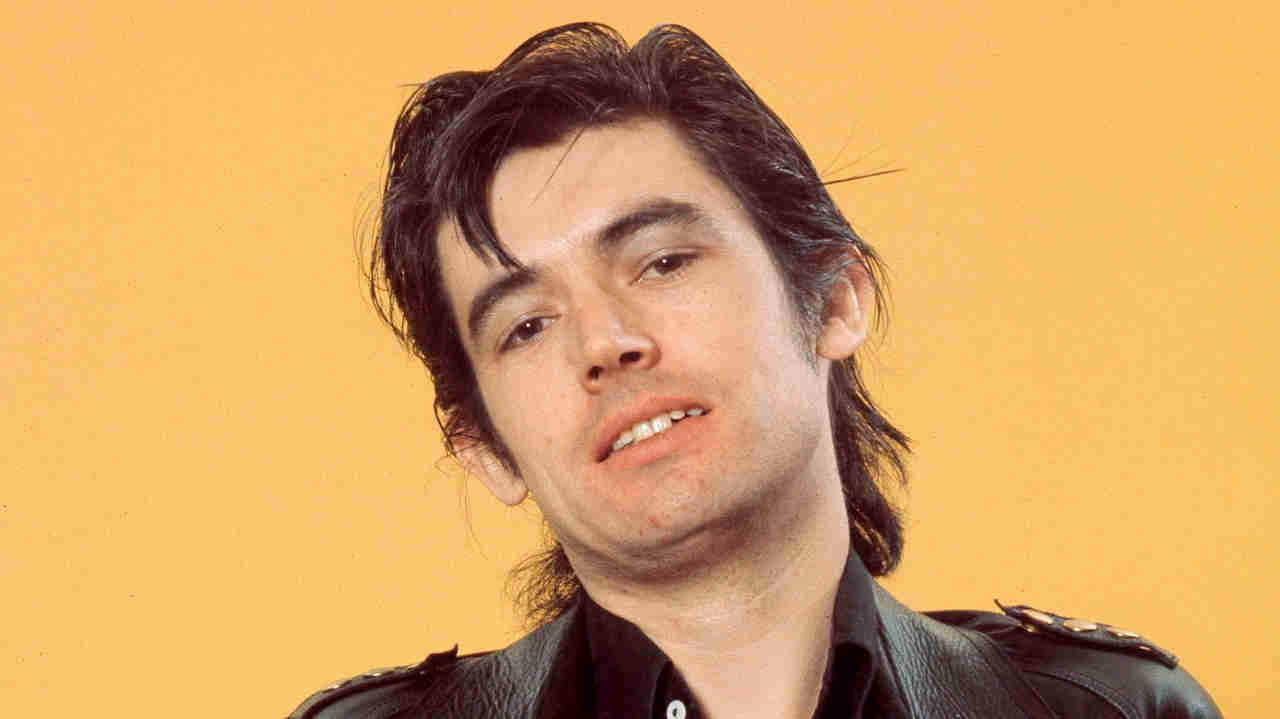

Before the Vince Neil car crash put a tragic and untimely full stop on Hanoi Rocks' career, the band had been on a brilliant path to greatness. By December 1984, having exploded onto a lacklustre rock scene blighted by vacuous new romanticism, post-punk austerity and backward-glancing metal Gumby-ism, the five glam-drenched sonic swashbucklers of Hanoi Rocks were about to go global.

After finally netting a major-label deal with CBS, the band had just delivered Two Steps From The Move, their fifth and most assured studio album to date. And as the second single taken from it, Underwater World, crept into the lower reaches of the chart, Hanoi Rocks prepared to embark on their inaugural American tour.

In the drab and dreary monochrome doldrums of the mid-80s, Hanoi Rocks were like an eye-scorching flash of amplified Technicolor; their extracurricular over-indulgence had already captivated the media, and their reputation as a live band was formidable. Japan had already fallen at the band’s feet, and it seemed almost inevitable that the United States would follow. Consequently, as the band touched down in New York, MTV was saturated with clips of the five-piece, gigs were comfortably sold out, and even Andy Warhol hovered expectantly at their star-studded welcoming bash.

Nothing, it seemed, could possibly go wrong. But it did. Catastrophically so. And it took Hanoi Rocks decades to recover from the aftermath.

The most cataclysmic chain of events can often be set in motion by something seemingly small and insignificant. The Hanoi Rocks tragedy is a case in point. At one of the opening shows of that ill-fated American tour, in Syracuse, a beer bottle fell from the top of guitarist Andy McCoy’s amp rig, and its contents spilled across the right-hand side of the stage. Just moments later, Hanoi’s acrobatic vocalist Michael Monroe leapt from the PA stack, skidded on the pool of booze, and fractured his ankle. Ever the trouper, Monroe finished the show before being whisked off to hospital.

Afterwards, suffering great pain, he sought medical advice. Following a misdiagnosis of severe sprain, the tour continued for four more dates – Toronto, Detroit, Chicago and Cleveland – before Monroe, now in constant agony, eventually sought a second opinion when they reached Atlanta, where a fracture was detected and a soft cast now applied to the break.

The remainder of the band, after flying down to Los Angeles, routinely ripped to the gills on a variety of intoxicants, were forced to kick back and twiddle their thumbs while Monroe recovered. But thumb twiddling was something they were never particularly good at.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

Birds of a feather flock together, and Hanoi Rocks’ unquenchable desire for partying had previously, and almost inevitably, brought them into LA band Motley Crue’s orbit. Hanoi’s ebullient drummer Razzle vaguely knew Crüe vocalist Vince Neil, and while in London Nikki Sixx and Tommy Lee had crash-landed at Andy McCoy’s flat to hang out and watch an AC/DC video. And although the two bands were never the closest of friends, they did share an unhealthy appetite for cavalier self-destruction. It came as little surprise, then, that as soon as the – temporarily derailed – Hanoi Rocks touring machine arrived in LA, Mötley Crüe held an impromptu welcome party for them.

With Monroe laid up in his hotel room, McCoy, Razzle, bassist Sam Yaffa and guitarist Nasty Suicide embarked on a mammoth drinking binge with the Crüe that was always destined to end in total, unmitigated disaster.

Sketchy memories from those in attendance suggest that three to four days into the party, on the evening of December 8, with supplies depleted, a trip to buy more booze was mooted. Vince Neil, heavily intoxicated but, inadvisably, keen to show off his orange-red 72 Ford Pantera sports car, set off for the liquor store with Razzle as his passenger.

Almost an hour later McCoy became concerned that the pair still hadn’t returned and, along with the band’s road manager, set about retracing their steps. As they drove they passed a car wreck near Neil’s home in Redondo Beach. Seconds later, and with chilling realisation dawning, they returned to the scene to find Vince Neil in police custody and Razzle’s unconscious body being put into an ambulance.

Apparently, shortly after setting off at 6.38pm, Neil lost control of his car in a wet spot while swerving around a stationary fire truck at 65mph in a 25mph zone. His Ford Pantera then careered into the path of oncoming traffic and was struck by two other cars.

The driver of one of them, 18-year-old Lisa Hogan, was rushed in a critical condition to the intensive care unit of the Little Company of Mary Hospital, where she remained in a coma until the end of the month with a broken arm and two broken legs. Brain damage, meanwhile, left her liable to psychomotor seizures. Lisa Hogan’s passenger, 20-year-old Daniel Smithers, suffered a broken leg and some brain damage. The driver of the third vehicle was thankfully uninjured.

Vince Neil miraculously escaped serious injury (suffering only cracked ribs and minor facial cuts), but Razzle was pronounced dead on arrival at Redondo’s South Bay Hospital at 7.19pm. Vince Neil was taken to the police station at nearby Torrance where he was immediately arrested on suspicion of drunken driving and vehicular manslaughter, but was subsequently released on $2,500 bail.

Eventually convicted in July 1985, the singer ultimately served just 20 days in jail, was ordered to pay $2.6 million in compensation to the injured parties, completed 200 hours of community service, and attended school and college lectures on the dangers of drugs and alcohol.

The timing of the tragic accident – December 8, 1984 – marked the first day of the USA’s National Drunk Driving Awareness Week. Neil clocked up an alcohol reading of 0.17 – well above the legal limit of 0.10. To make matters worse, neither he nor Razzle were wearing seat belts at the time of the crash.

‘You know, I don’t care if I fucking die. I just want to get to LA’

Razzle

Nineteen years on from that fateful day, Andy McCoy was still mourning his lost ‘brother’. Ensconced in the lounge of London’s decidedly plush Charlotte Street Hotel, his bejewelled fist wrapped around the latest in a long line of generous Bloody Marys, McCoy was every ounce the rock star.

His swarthy countenance etched with hard-won experience, eyes blackened from lack of sleep – he attended an awards ceremony the previous night, hadn’t slept since, and was apparently entertaining patrons at a Lebanese restaurant until the early hours of the morning playing an ornamental bazouki – and with gold teeth flashing, bandanna-and-stetson combo framing bony tresses, and an ash-flecked, £1,000 made-to-measure suit hanging stylishly from his seemingly indestructible bones, he couldn’t help but turn heads. His voice was reduced to a croak from the tomb, and as he spooled back almost two decades you could not help but realise that this recollection of times past was in grave danger of breaking his Romany heart.

“I had totally cleaned up my act and we were gonna work hard,” he recalls of his ill-starred American nightmare. “Some of the other guys had a different attitude – it was party, party, party, party till you fucking drop. But that was mainly Nasty and Razzle. I remember Zeppo, our manager, having a heavy speech with Razzle: ‘You’re gonna kill yourself if you keep partying this way’. And I remember a drunken Razzle standing there, quietly listening to him slagging off his lifestyle, and he just looks up and says: ‘You know, I don’t care if I fucking die. I just want to get to LA’. And he got to LA. He just never got to enjoy it. And I just wish he had.”

I ask him what his abiding memory is of December 8, 1984.

“Identifying his body,” he replies solemnly. “Having to ring our manager to bring the guys to the hospital. I just couldn’t tell them over the phone. And when they got down there I had already identified him so that nobody else had to see his smashed-up head. I told them what the doctor told me, which was the most important thing: he hadn’t suffered at all… may he rest in peace.”

McCoy seems lost in thought for a moment, and as his eyes cloud and darken with a mixture of grief, sadness and rage he slowly and deliberately crosses himself, before resuming with noticeable steel in his cigarette-ravaged voice.

“About a month before he died, we saw a picture of a wrecked car where people had died when going over the speed limit. It was like a dark omen, that looked just like the scene of the crime. Because it was a crime. Not only did Razzle die, two young people got crippled. And this guy sat one night in jail, got away with a misdemeanour. If he would have been a broke Afro-American guy or Latino he would have been doing life in San Quentin.”

To say that there is a vitriolic antipathy between Andy McCoy and Vince Neil is a profound understatement. At the heart of this time-honed bitterness lies a seemingly unforgivable lack of contrition: “He never apologised.” McCoy shakes his head with undisguised disgust.

“He’s scared of me. Every time he sees me he runs away. But to me it is so important, it is the moral value of the thing. The other Mötley Crüe guys apologised, but the other guys didn’t do anything wrong. They were fucking so pissed off with him that Motley Crue almost broke up that day. Tommy just wanted to beat the shit out of the fucker. He’s got ‘PMUSA’ tattooed on his ass – prime meat from the United States; fucking hell, I’d say prime piss… prime pussy USA.

“We could have sued over Razzle and gotten millions, but I was the one that put a stop to that. There was talk about that and I said: ‘How the hell can we put a price on a brother, a family member? There isn’t enough money, you can’t put it in money. Let him live with it, let karma get him’. And it has. He just doesn’t seem to get out of trouble. But as he made his bed, he will sleep in it.”

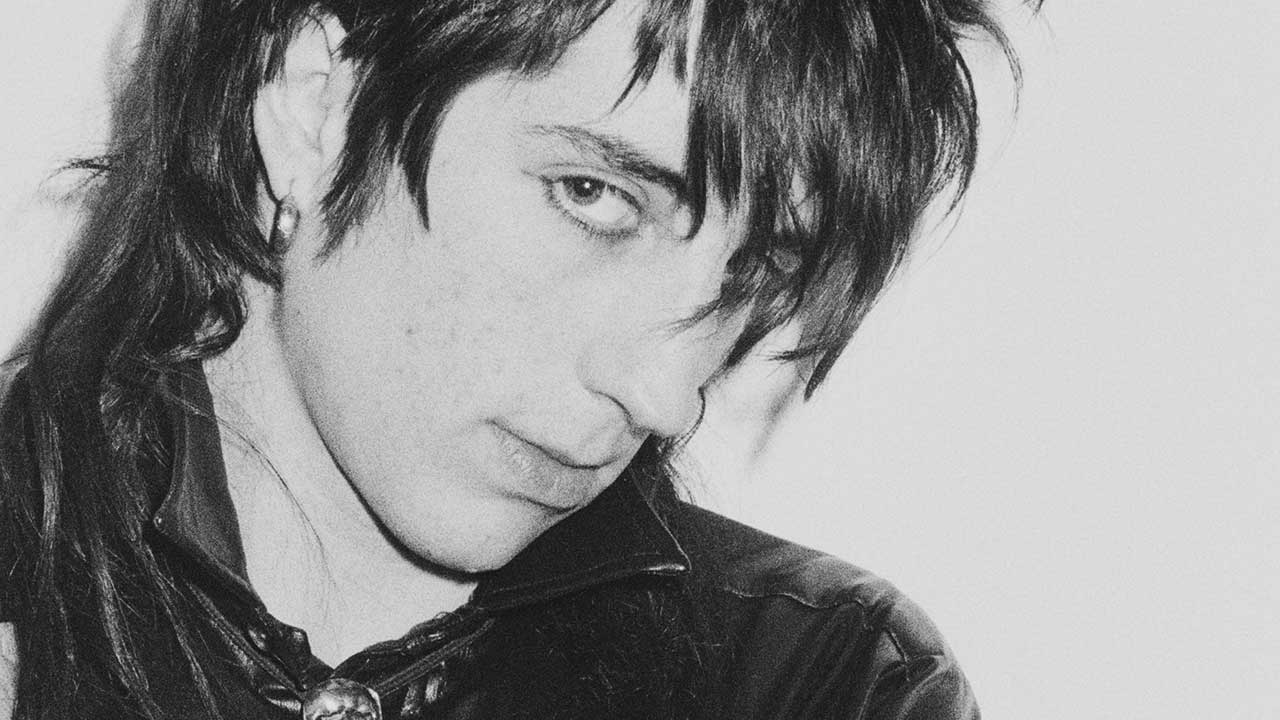

Michael Monroe, meanwhile, is loath to dwell on the loss of a dear friend. Still possessing the most astonishingly high cheekbones and voluminous hair in rock, he remembers Razzle as the band’s “heart and soul”. Razzle was also the only member of the Hanoi Rocks boozing fraternity who actually took time out from the endless imbibing to ask after the teetotal vocalist’s health.

“When he joined we were at a really low point, and he saved the band,” Monroe recalls. “Razzle was my best friend and brother, the person who when I was in a bad place would always come around and say: ‘Alright mate, I know what you’re going through’. He was always keeping the spirit up.”

Even during Hanoi Rocks’ most hard-living years, Monroe eschewed alcohol: “I was never happy drinking, it makes me sick.” And as a consequence, life with four of rock’s most infamous hell-raisers certainly had its downside.

“On that American tour everyone was fucked up out of their minds 24 hours a day, mainly drinking,” the singer says. “So I was not having much fun, but I would sit there and drink my orange juice and just put up with it. It was boring, really, because whenever we would go to rehearsals, after half a song it would be: ‘Fuck it, let’s go to the pub’.”

Even now, every time that Monroe, orange juice in hand, begins answering a question, McCoy and his vodka have a habit of butting in.

“Nasty was the one who was really the heavy drinker,” volunteers the chain-smoking man in the pinstripe suit midway through Monroe’s testimony: “He ended up in a kidney machine. Once he drank my aftershave because the mini-bars were empty.”

“Fucking hell, Andy, let me finish my story or we’ll be here all day!” snaps the statuesque blond bombshell with the Job-like patience. And as McCoy mumbles on, oblivious, about terrorising Tel Aviv, Monroe returns once more to the worst day in Hanoi Rocks’ history.

“So anyway, I was in my hotel with my foot in a cast. The guys went out partying, and Vince was fucked up on whatever. He took Razzle out driving and couldn’t handle his car; he was trying to show off. Now, Razzle had been in an accident when he was younger. He was paralysed from the neck down at one point, from a bike accident that he had, and so he was a safe driver. If I had been in that car it probably wouldn’t have happened.

“And after that, Motley Crue made those fucking videos with car crashes and shit. Imagine a kid paralysed because of this guy, and he’s on TV hitting a burning car? That to me is totally ignorant, insensitive and stupid.”

How did you find out about Razzle’s death?

“Our manager Zeppo called me at the hotel and said that Razzle was gone – ‘He’s dead.’ And I was like: ‘Are you sure there’s nothing can be done?’. And he’s like: ‘No. He’s gone, he’s dead’. I just hung up the phone. The roadies were in the room waiting to hear, because we knew something bad had happened. When I heard that, I just broke down, and said to the guys: ‘Razzle’s dead’. They said: ‘What!’. And I went to my room. That was a miserable time, and everything turned to shit. So can we move on?”

“When Razzle passed away,” McCoy volunteers, “Sammy left the same minute. Me, Michael and Nasty were like three lost children. We couldn’t keep our own lives together, so how were we going to keep a band together?”

How indeed?

One factor that is often overlooked in the rose-tinted retelling of the Hanoi Rocks saga is that Sam Yaffa had already announced his intention to leave the band even before they’d set off for the United States. He, at least, recognised that the Hanoi Rocks lifestyle was utterly unsustainable over the long haul and decided to quit one step ahead of his liver. The band’s inexorable rise had been one hell of a ride, and Sammy wanted to get out while the getting was good. Unfortunately, on December 8, 1984, the cruelties of fate beat him to it.

From the outset, Hanoi Rocks had been Andy McCoy and Michael Monroe’s baby; in fact Monroe now looks back on past band members as “good soldiers, but soldiers all the same”.

McCoy had already enjoyed a triple-platinum album in Scandinavia with his punk band Pelle Miljoona before he and Monroe initially hooked up in the crypt of a Helsinki church to form “the ultimate rock’n’roll band”, a heady combination of The Faces, the Rolling Stones, the New York Dolls, Mott The Hoople, Alice Cooper and Johnny Thunders’ Heartbreakers.

Monroe (born Matti Fagerholm) had grown up in Helsinki where his father was a radio announcer, while half-Romany, half Finnish/Swedish McCoy (given name Antti Hulkko) had been brought up in Stockholm.

“My grandfather was a virtuoso Romany musician, and he started teaching me gypsy and flamenco guitar when I was four,” McCoy reveals. “I remember being a tiny kid going to visit my grandparents, and out of 30-something grandchildren he chose me to teach. I went on to the classical guitar, had lessons, and at seven or eight the teacher told me he couldn’t teach me any more; it had got to the point where I had to start teaching him. Then Marc Bolan came into my life and I had to get an electric guitar to play like him, and I suppose the rest is pretty much history.”

McCoy left home at 13, as is the Romany tradition, and immediately formed his first band, Briard. McCoy and Monroe’s inaugural line-up was almost called Chinese Rocks (a particularly potent strain of heroin ‘popularised’ in the song of the same name by Thunders), until sense prevailed and Hanoi Rocks was born.

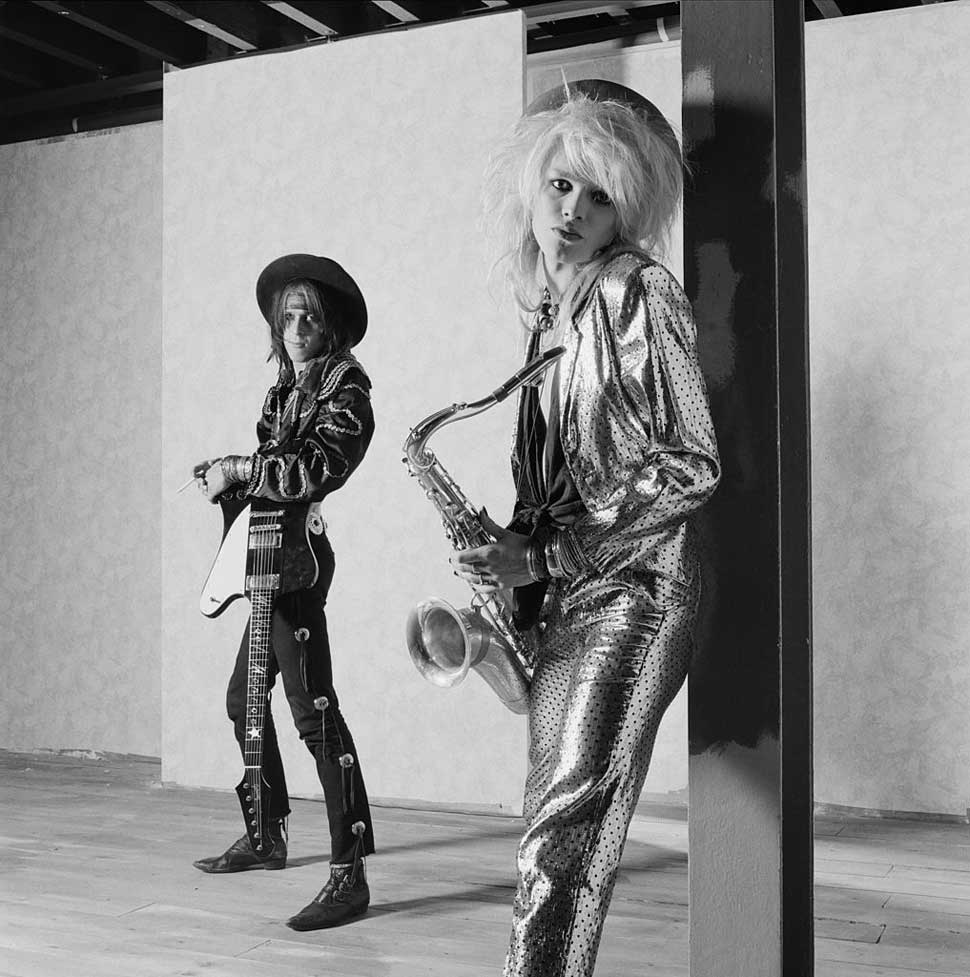

With a line-up completed by ex-Briard Nasty Suicide, former Pelle Miljoona Sam Yaffa, and drummer Gyp Casino, the band made haste for the UK, ‘cleaned up’ (ahem) on the live scene and – pausing only to replace newly dragon-chasing “suicide candidate” Casino with chirpy, cockernee geezer Razzle (aka Nicholas Dingley, and actually born as far out of earshot of Bow Bells as the Isle of Wight) – made five albums that you really ought to own.

On signing to CBS the band enlisted priceless production assistance from Bob Ezrin (Alice Cooper, Lou Reed, Pink Floyd, anything that’s any good, basically) and came up with Two Steps From The Move, an album of such range, power, humour, dynamic brilliance and overall maturity that unlimited access to the upper echelons of international celebrity – along with keys to the executive Charlie goblet – seemed to be theirs for the taking; they were even on Cheggers Plays Pop, for God’s sake. And then, in quick succession: Yaffa hands in his notice; beer spills in Syracuse; pissed-up Vince says: “Look, mum, no hands!”; and wallop, welcome to Shitsville.

So what happened next?

“I didn’t care anymore,” McCoy says at breakfast the following afternoon. “I was lost. I got back into heavy drugs, I just didn’t care. Something was missing. I think I was in shock still. But we had to work, and Razzle had been looking forward to these so-called Europe-A-Go-Go gigs.”

Finland’s contribution to this live, continent-wide telecast was originally expected to be Hanoi Rocks’ ‘triumphal’ return to Helsinki, but instead 300 million people tuned in to witness one of the most harrowing rock performances ever filmed. Terry Chimes, formerly of The Clash and Generation X, deputised behind the kit, while a clearly distraught Michael Monroe stumbled on his fractured ankle and choked back bitter tears of agonising loss.

Andy, Sam and Nasty, meanwhile, seemed paralysed into virtual stasis, should even the slightest shared glance cause total emotional collapse. Helsinki also marked Sam Yaffa’s last performance with the band. Monroe had known for weeks of the bassist’s intention to leave, but was shocked that he didn’t reverse his decision, at least temporarily, while the band struggled to find their feet in the wake of their shared loss.

“If he had stayed then maybe there would have been a better chance. But not only did we lose a drummer, we also lost Sammy, so the whole rhythm section was gone. We should have taken six months off, believe me, but they [CBS] were trying to rush the whole thing. And then we had this Rene Berg…”

Ah yes, the semi-legendary Rene Berg who died in August 2003. No one seems particularly keen to admit any responsibility for the latterly late and formerly wayward bassist’s recruitment.

“That wasn’t my decision,” McCoy blurts. “That was the first time that I left it in the hands of Mike and Nasty, and that was a mistake. But I wanted to straighten my head out, and I went away to Sri Lanka and the Maldives, just walking on the beach alone, stopped using all drugs. And I get back and he’s [Berg] in the band, and I couldn’t believe it. Fucking hell, he was a sweet enough guy, but he was never a Hanoi Rocks member. On the last tour of Poland he couldn’t open his suitcase, so I went downstairs to get a knife and fiddle with it, and it exploded open and about 200 pills in all different colours fell out. I’m like, ‘Oh my God, not another one’.”

“He was the first one to turn Andy on to smack,” Monroe continues, “and that was why I always hated him. With him there was always a pill for everything. He was like a fucking walking medicine cabinet. His attitude totally sucked. He wanted to get famous and have all the little girls, he was really disgusting. I didn’t even introduce him on stage.

"I took his passport as we were going through immigration in Poland, and had him squirming in agony for a while. And I remember coming into the country and there were some interview people there, and I just walked past them and Andy did too, but he stopped. And they said: ‘What is Hanoi Rocks?’ And he said: ‘Oh, it’s a lifestyle.’ And I was like: ‘Look, Andy. Look at this fucking prick.’”

“May he rest in peace,” McCoy concludes with surprising, if belated, sensitivity.

The penultimate straw came when, in another curious decision, Johnny Thunders was brought in to produce some demos.

“That was fucked up, because Andy asked him to produce the demos and Andy wasn’t even there,” Monroe says. “Nasty, Terry Chimes and Rene Berg were doing this song that they were rehearsing over and over, Nasty’s all pin-eyed in asshole heaven, and I was with Johnny listening to the tracks. I had a cool idea that I played on the harp, and Johnny said: ‘Go in there and put it down right now.’ He went into the studio and said: ‘Will you guys take a break for five minutes so that Michael can put this harp idea down?’ And Nasty was going: ‘We’re rehearsing here.’

"So Johnny said: ‘You’ve rehearsed the song 30 times already, can’t you take a little break?’. So Nasty said: ‘Fuck that’, and Rene Berg said: ‘And fuck off, Johnny’. So Johnny said: ‘Mike, fuck this, I’m out of here’. I said: ‘So am I. Fuck all you motherfucking bastards’. And that’s when I decided that’s it. How could they disrespect Johnny like that, sitting there all smacked out of their brains? Fucking bullshit.”

And then they went to Poland. “That was a tour that had been agreed, and I don’t know what the fuck we were doing there,” Monroe shrugs. “I thought we were all gonna die. And we almost lost Nasty. Nasty was left behind with only his socks on. We drove for hours after that, while he was sleeping on the side of the road hearing wolves howling and shit, all in darkness.”

“We had a shopping bag full of weed which we had bought for 10 bucks,” McCoy explains. “I thought it was silly at first – it can’t be this cheap, this is a set-up, man. We’ll end our lives rotting in some Polish communist basement prison and be forgotten about. But after a day I thought it’s not a set-up.

"So we started smoking it everywhere, like in hotel lobbies. And this photographer that was with us had had a little bit too much and hadn’t slept for three days and was running around rambling in Italian, and I was like: ‘Shut up or I will punch your head in’. So he was saying we’d left Nasty, and we were saying: ‘Yeah, right’, because we’d been listening to his serious bullshit for three days, so no one would believe him. And then seven hours later we arrived at the hotel, and sure enough Nasty is missing. And we only stopped for a leak, man.

"So he had no shoes on, no shirt, only a pair of suit trousers; no papers, no identification, and no idea where he had played the night before or where we were going. He was sleeping at some bus stop by the side of the road when we did eventually find him.”

So how did it all end? “There was no massive bust-up,” Monroe admits. “It was just like: ‘I never wanna see you again. Stay out of my life’. Well the first thing I wanted to do was clear my mind; I wanted to get Andy off of my back, because although he wanted to work with me he had never said that he needed me or acknowledged me. All I needed to hear was ‘I need you to work with me’ or something. But he was too proud then, and I thought, he has to learn to have a little bit more respect…”

“I was a street kid and I was an asshole,” McCoy interjects miserably. “Very hard, my head wasn’t all there.”

“Everybody was a little out of it in their own way,” Monroe offers, making no small understatement.

“It was a very sad time,” McCoy concludes. “Our lives had been destroyed because of a drunken idiot.”

Against the odds, Hanoi Rocks were back once more in 2003, with the stunning return-to-form Twelve Shots On The Rocks album. How did McCoy see their future?

“I see a very long future,” he smiles, with a flash of his piratical golden gnashers, before croaking modestly: “I see this band basically taking over from the Stones, because they are gonna retire soon, and there’ll be a massive gap that has to be filled and Hanoi Rocks is the band for the job. Rock’n’roll is such a funny thing. It’s just three-, four-minute songs but it seems to change people’s lives and make people feel good. And if I get paid to make people feel good without having to whore myself physically, then I guess that I’m blessed.”

This feature was first published in Classic Rock issue 61, in December 2003.

Classic Rock’s Reviews Editor for the last 20 years, Ian stapled his first fanzine in 1977. Since misspending his youth by way of ‘research’ his work has also appeared in such publications as Metal Hammer, Prog, NME, Uncut, Kerrang!, VOX, The Face, The Guardian, Total Guitar, Guitarist, Electronic Sound, Record Collector and across the internet. Permanently buried under mountains of recorded media, ears ringing from a lifetime of gigs, he enjoys nothing more than recreationally throttling a guitar and following a baptism of punk fire has played in bands for 45 years, releasing recordings via Esoteric Antenna and Cleopatra Records.