“We opened for bands we really hated, like Styx. People were relating to us and not them. They got a little pissed”: the stellar rise and sudden fall of The Cars, the new wave band who soundtracked America

For nearly a decade in the late 70s and early 80s, The Cars were one of America’s most popular bands

In the late 70s and early 80s, The Cars were one of America’s most popular bands, effortlessly knocking out hits such My Best Friend’s Girl, Shake It Up, You Might Think and Drive before their split in 1988 following the departure of co-vocalist and chief songwriter Ric Ocasek. In 2005, as guitarist Elliott Easton and keyboard player Greg Hawkes prepared to launch The New Cars, the former members talked Classic Rock through the career of the band that soundtracked the new wave era.

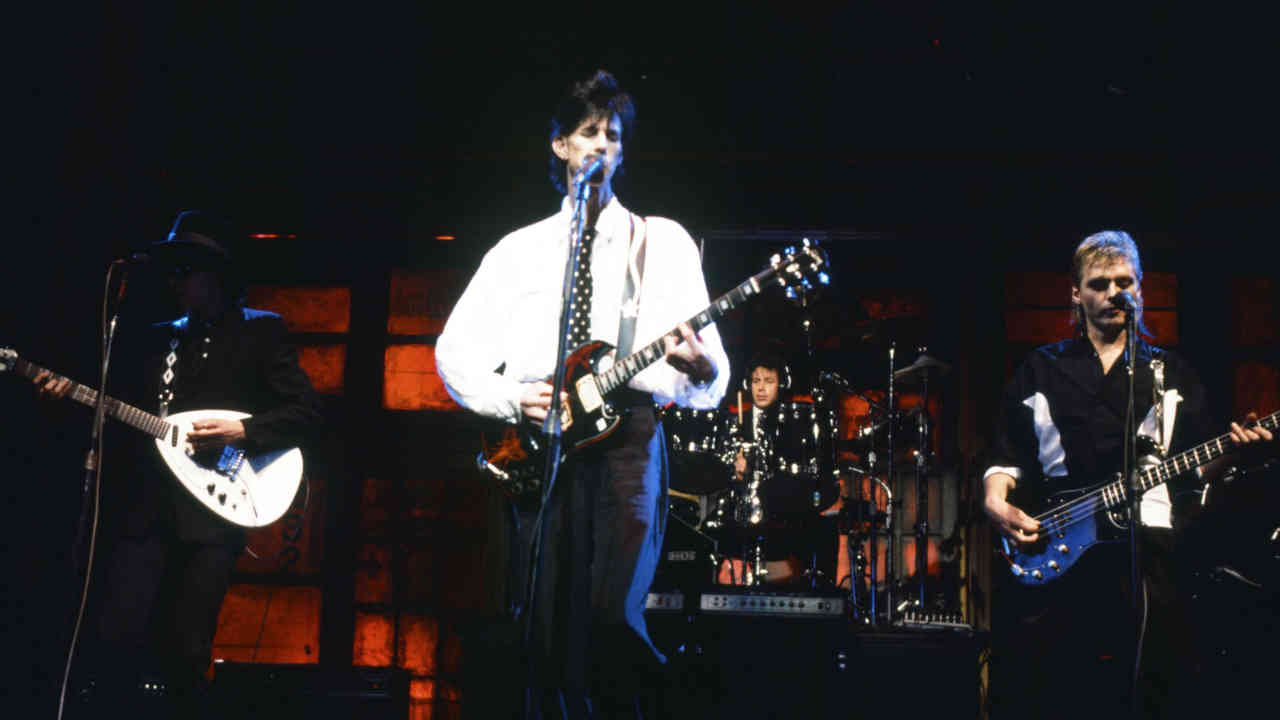

Led by singer/guitarist/songwriter Ric Ocasek, The Cars were the prototypical new wave band. Scoring a string of hit singles during the late 70s/early 80s, selling out arena tours and becoming darlings of MTV, it appeared the band could do no wrong.

But by 1988 the once tightly knit group had completely unravelled. A decade later, Ocasek explained that the situation hadn’t improved: “We don’t keep in contact at all,” he said, “apart from I see Greg quite frequently. But I haven’t seen Elliot in a few years, I haven’t seen Ben in about eight years, and I haven’t seen David in about three years. We don’t talk on the phone. We’re pretty much a dysfunctional family.”

It wasn’t always that way. Ocasek, from Baltimore, and Ben Orr, from Cleveland, got together in the early 70s when they moved to Boston. There they put together a short-lived folk group before returning to their true love, rock’n’roll, and formed Richard And The Rabbits followed by Cap’n Swing. It was during this time that Ocasek and Orr brought in keyboardist Greg Hawkes, guitarist Elliot Easton and drummer David Robinson (a member of proto-punkers The Modern Lovers).

Easton recounts his first impressions of Ocasek and Orr: “They were playing at a Warner Brothers party for Foghat. I remember being very struck because it was the first local band I’d ever heard in Boston that was doing their own music – really strong. I distinctly remember having the thought, ‘I want to play in this band’.” He didn’t have to wait long.

By 1977 the four-piece had settled on a new name, The Cars. The songs and sound were in place – a blend of what would become known as new wave (Hawkes’s synths, Ocasek’s muted power chords) and arena rock (stadium-ready choruses, Easton’s guitar heroics) – with Ocasek and Orr splitting the lead vocals. The band had a hard time landing a deal, though, despite interest from Kiss’s manager, Bill Aucoin. But for The Cars the onramp to the fast lane was just around the corner.

Ocasek: “Our demo tape got played on the radio – Just What I Needed became a hit before it was even on a record. WBCN in Boston was playing it, and it became the most requested song. Record companies started coming around asking: ‘What label are they on?’ So then we had 20 labels chasing us around Boston.”

Classic Rock Newsletter

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

A record deal with Queen’s then US label, Elektra, was signed, and the group flew to England to work on an album with another Queen connection, producer Roy Thomas Baker.

“That was way exciting,” Hawkes enthuses. “We got to go to London, and recorded at AIR Studios, George Martin’s studio, which was a thrill. Got to meet him there. The studio was great, getting to work with Roy Baker was great. We did it in like 12 or 14 recording days, and then mixing was approximately a day per song. We had the whole thing recorded and mixed during February 1978.”

From the off, it was clear that The Cars had one songwriter in the band: “Our band never jammed, I wrote all the songs,” he says. “I put them down on tape, with the parts on, and people learned the songs,” he explains. “I’ve never done a song by jamming with somebody else. I don’t like the idea of it. I don’t like to write with others. I started The Cars to play music that I wrote, just like I’ve started any band that I’ve ever had. I form bands to play my songs.”

The Cars was released in June of the same year, and began a slow-but-steady climb up the US chart, ultimately reaching the Top 20 thanks to the success of the hits Good Times Roll, My Best Friend’s Girl and the aforementioned Just What I Needed.

Like most up-and-coming bands, The Cars ‘spread the word’ by opening for a variety of established bands, which that year included Bob Seger, Thin Lizzy and Cheap Trick.

“We opened for about anybody in the beginning; we opened for bands that we really hated, like Styx,” Ocasek says. “Most of those bands would go watch us on the side of the stage to see what the fuck was going on. And it seemed that the people were relating to us and not relating to them. So they got a little pissed.”

In Spring 1979, The Cars played their one and only European tour. Hawkes remembers it fondly, something Hawkes remembers fondly. “English audiences were generally very positive. I think it was more the English critics that were less positive. It was the heyday of punk rock, so I think we were thought of as an ‘American corporate entity’, although I would disagree with that. I guess in comparison to The Sex Pistols and The Clash we were a little too ‘pop’.”

With The Cars still riding high in the US charts, in 1979 they released their second album, Candy-O. The album stormed the US charts and peaked at No.4 (its lead-off single Let’s Go narrowly missed the Top 10), which resulted in the group playing huge venues. However, Hawkes voices the downside of playing hockey arenas: “It starts getting more remote, and it’s harder to connect with the audience.” Indeed critics were quick to point out the group’s often ‘cold’ vibe on stage – they rarely chatted with the audience, and Ocasek hid behind ever-present sunglasses.

While The Cars’ first two albums focused mostly on radio-ready pop ditties, on 1980’s Panorama the mood grew darker and artier. Easton claims it wasn’t intentional, however: “At the time, people said it was a great departure and it was more experimental. I don’t think we were really thinking of it that way. It was just that year and that batch of songs. It’s only with hindsight that you say, ‘Maybe there were some stylistic departures, and maybe we expanded our palette a little bit.’ I still love Touch And Go off that record.”

Taking barely any time off, the group built their own Boston-based studio, Synchro Sound, and dived headlong into their fourth album in as many years, 1981’s Shake It Up. With fans wondering if The Cars were going to continue in their new-found arty direction, the group returned to their earlier, snappy new wave pop style, and enjoyed their fourth consecutive Top 10 album.

Easton recalls the group getting along better than ever. “It was fun. I was a single guy and pretty crazy,” he says. “The thing that people don’t understand is that it was a very funny band. We had this sort of cool, detached image, but those guys were really funny people. Experiencing all these things for the first time… it was still fresh. We were tight.”

Looking to recharge their batteries, The Cars took their first-ever break once the Shake It Up tour wrapped up. Ocasek filled his free time producing others (Suicide, Romeo Void, Bad Brains), and in ’82 also released his debut solo album, Beatitude.

After having their first four albums produced by Roy Thomas Baker, The Cars decided to enlist the aid of Mutt Lange, who had just produced two of the decade’s top-selling rock releases: AC/DC’s Back In Black and Def Leppard’s Pyromania. As with their debut, the group set up shop in England, but unlike the short amount of time it took to record The Cars, this time they would be at it for almost a year.

“It took a long time to make that record, because that’s just how Mutt likes to work,” Easton says. “He was trying to get the technical perfection, but he was also trying to make it sound like you picked up the guitar and ripped it off in one take. He was going for the perfect take technically, but also to have spontaneity. They’re such contradictory things, so difficult to achieve, that it just takes time.”

The wait was certainly worth it, however. released in 1984, Heartbeat City charted high and spawned four US hit singles: You Might Think, Magic, Hello Again and Drive. All had imaginative videos shot for them for the then-burgeoning MTV, and the band picked up the award for Best Video Of The Year for You Might Think at the first-ever Video Music Awards.

With yet another sold-out arena tour completed, 1985’s best-selling Greatest Hits, and Drive memorably used over some emotive footage at Live Aid (helping enormously the group having their biggest hit in the UK with that song), no one could have foreseen that The Cars were fast approaching the end of the road.

For reasons no one is exactly sure of, tension grew between Orr and Ocasek during the recording of 1987’s Door To Door. Roberts: “It just didn’t feel as ‘up’. Ben seemed to not be completely present. I think Ben didn’t want to tour, he wanted to stay in Hawaii.”

Hawkes: “Door To Door was very unpleasant. At that point Ric and Ben were barely speaking to each other. I can’t even listen to the album, to tell you the truth. All I can hear is bad vibes [laughs]. I haven’t even tried to listen to that for at least 10 years. To me that was like the ‘lost’ Cars record, because I’ll probably never listen to it again.”

Comprised mostly of re-recorded left-overs from earlier albums, Door To Door peaked at No.26 in the US – well below its predecessors. Poor album sales and tour attendances, combined with increased intra-band tensions (Hawkes: “There was friction all over. Everybody was just sort of tired of each other”), led to the tour being scrapped mid-way through.

Easton recalls receiving a bombshell from Ocasek shortly thereafter: “I was at Electric Lady [studio] with Ric, and we were listening to tapes for a live radio broadcast. It was before the holidays, and at a quiet moment he said: ‘I wasn’t going to say anything until after the holidays, but I’m leaving the band.’ It wasn’t like it broke up in any kind of argument, or even formal way with all of us sitting together and saying: ‘That’s it.’”

Although the group members each went their separate ways (some focusing on solo work, production and playing with others), though the members – minus Orr – got back together in the 90s to discuss a possible reunion. “We were at the studio for a couple of days, three days tops,” Hawkes reveals. “But that’s all that happened. I think the intention was: ‘Let’s get together and see what it feels like, see what it sounds like, and see if we should proceed.’ Which I guess we didn’t do.”

Even after the friction towards the end, the original line-up buried the hatchet for a group interview that accompanied their 2000 DVD release The Cars Live: Musikladen 1979. Sadly, Orr had been diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, and the illness had taken its toll on the appearance of a man who once possessed pin-up looks. On October 3, 2000, just a few months after the taping, Orr passed away, aged 53.

Despite The Cars’ sedentary state throughout the 90s, they received a boost when bands including The Smashing Pumpkins and Nirvana began covering Cars classics; the Pumpkins tackled You’re All I’ve Got Tonight for their The Aeroplane Flies High box set, Nirvana played My Best Friend’s Girl at their last ever gig. Additionally, Ocasek became a sought-after producer (he worked on both of Weezer’s self-titled albums), and The Cars’ own records continued to sell. Despite Orr’s passing, rumours of a reunion gained steam.

“We tried to get back with the four of us,” Easton says, “but ultimately I think [Ocasek and Robinson] had moved on in whatever way. When Ric made it clear to us that he really no longer wished to tour, and Greg and I wanted to do this thing [get The Cars moving again], we sort of cast about for who we could get to be in the band. I came up with a very short list, and Todd Rundgren was at the top of it. To my very pleasant surprise, he was receptive to the idea and said he wanted to give it a try.”

With Rundgren taking Ocasek’s seat, and his longtime bassist Kasim Sulton and The Tubes drummer Prairie Prince also on board, with some shiny new hubcaps The New Cars were driving again in late 2005.

Playing in front of an invitation-only audience on a Los Angeles soundstage in January this year, The New Cars recorded a set of hits which, packaged along with with three brand new Rundgren/Easton/Hawkes compositions, later released as It’s Alive.

Although Easton and Hawkes have not spoken to Ocasek about his thoughts on The New Cars, Easton did come across some encouraging words from his former bandmate. “I read in some press thing that Ric

did, where he said he just wanted to see Greg and I be happy,” he says. “I thought that was a very nice thing to say, and I wish him the same.”

Originally published in Classic Rock issue 93. The surviving members of The Cars reunited for 2011’s More Like This album. Rick Ocasek passed away in 2019

Contributing writer at Classic Rock magazine since 2004. He has written for other outlets over the years, and has interviewed some of his favourite rock artists: Black Sabbath, Rush, Kiss, The Police, Devo, Sex Pistols, Ramones, Soundgarden, Meat Puppets, Blind Melon, Primus, King’s X… heck, even William Shatner! He is also the author of quite a few books, including Grunge Is Dead: The Oral History of Seattle Rock Music, A Devil on One Shoulder And An Angel on the Other: The Story of Shannon Hoon And Blind Melon, and MTV Ruled the World: The Early Years of Music Video, among others.