The rock star was hardly a novice. It was the late 1970s and he’d seen plenty of drugs and groupies. He also knew that his record company, Casablanca, had become a byword for excess. So it wasn’t a complete shock when he strolled into their offices one afternoon to find a member of another Casablanca act screwing a male employee over his desk.

According to Casablanca co-founder Larry Harris, it was Gregg Giuffria, keyboard player with Washington DC pomp-rockers Angel, who witnessed his labelmate in flagrante.

“He was about as fazed at the sight as I was at hearing about it, which is to say, not at all,” Harris admitted. “That was Casablanca.” Just another day at the office.

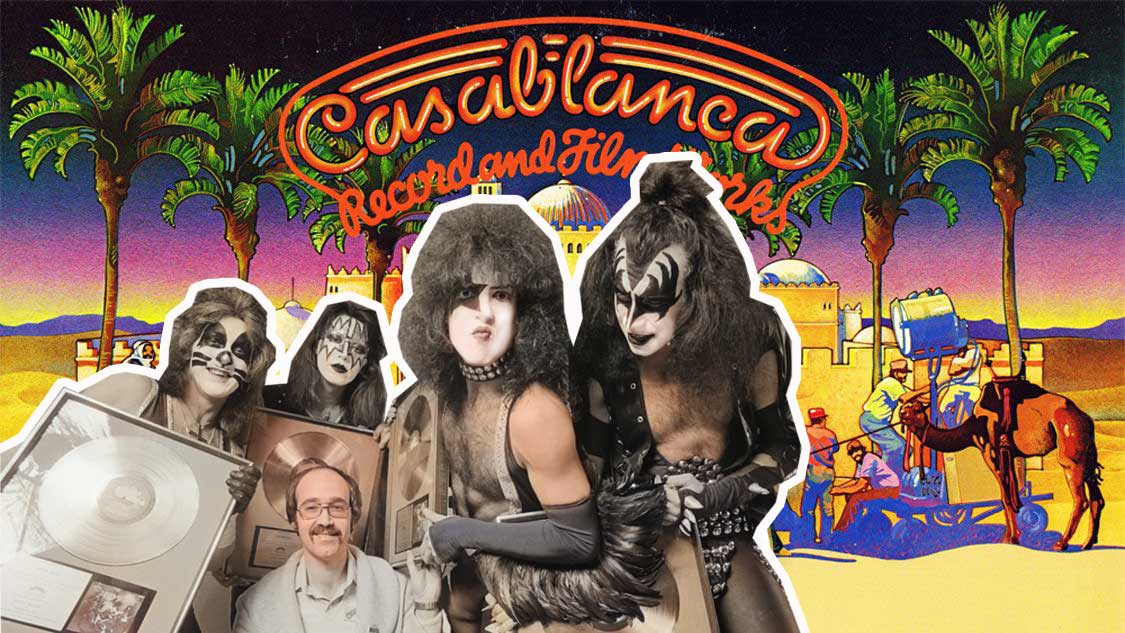

In the 70s, Casablanca was home to a motley crew that included rock monsters Kiss, funk pioneers Parliament, dance queen Donna Summer and disco troupe Village People. “It was,” says Kiss’s Gene Simmons, “a place for rogues and rebels and people that broke the rules.”

Casablanca’s mottos included ‘The sky’s the limit’ and ‘Whatever it takes’. It was the record label that hustled more than any other; that ran on a seemingly endless supply of booze and cocaine, and where everyone flew first class and rode around in limousines. Casablanca was the essence of 70s excess. But it also broke new ground in the music business.

The man at the heart of it all was label head Neil Bogart. Born Neil Bogatz in February 1943 in a New York housing project, he always dreamed of being in show business. But when a job singing on cruise ships didn’t last, he turned to what he did best: selling. Neil Bogart could sell anything – including coat hangers. And when sales stalled, he customised them. “He stuck a red frilly bow tie on his hangers so he could sell more,” says Gene Simmons, “and it worked.”

In a sense, Bogart stuck the equivalent of that red frilly bow tie on his Casablanca artists: be it Simmons’s fire-breathing act with Kiss or Parliament’s levitating ‘Mothership’ stage set.

By 1971, Bogart was working as an executive at the independent Buddah Records, whose releases included avant-garde bluesman Captain Beefheart’s Safe As Milk, but also the bubblegum pop singles Simon Says by 1910 Fruitgum Company, and Ohio Express’s Yummy Yummy Yummy.

Bogart would bring a similar eclecticism to Casablanca, the label he set up in 1973. As his business partner Larry Harris observes in his memoir And Party Every Day: The Inside Story Of Casablanca Records, their fortunes changed when they “adopted the ploy of selling Neil” to potential investors.

Bogart dazzled Warner Brothers’ top executives with his charm and bravado, leading to the label giants offering Casablanca a seven-figure financial backing and distribution deal. All they needed now was a band.

Bogart was willing to sign Kiss on the strength of their demo tape alone. But when the face-painted rockers showcased for him at a ballet school in Manhattan in September ’73, he had reservations.

“Neil didn’t like the makeup,” recalls Simmons. “But we had the king-size balls to tell him, ‘The makeup stays.’” Realising Simmons’s balls were as big as his own, Bogart signed Kiss.

Casablanca celebrated their launch on February 18, 1974, with a $45,000 party at Los Angeles’ Century Plaza Hotel. Kiss let off so many smoke bombs, some guests fled for safety before they’d even played a note. Once Bogart accepted Kiss’s larger-than-life image, he helped make it even larger, suggesting an elevating drum riser and convincing Simmons to breathe fire as part of the act.

On a trip to a magic shop to buy stage props, Bogart discovered ‘flash paper’, a material used by magicians to create little fireballs in their hands. “Neil fell in love with the stuff,” recalled Larry Harris. “We’d be meeting with DJs, promo men, and he’d suddenly say, ‘Kiss is magic!’ and unleash a flash-paper flame. It never failed to impress.”

“Bogart was like PT Barnum in [the circus company] Barnum & Bailey,” adds Simmons. “One of the last great showmen.”

But no amount of magic could make Kiss’s debut album sell. Kiss was also a strange choice for the man behind a score of bubblegum pop hits. “For a guy whose career had been based on hit singles to have a band that didn’t have hit singles seems remarkable,” says Simmons. “But to his eternal credit, Neil let Kiss be Kiss.”

Casablanca’s next major signing was similarly offbeat. Parliament were a vehicle for shamanic frontman George Clinton, and fused soul, jazz and doo-wop with stoned, stream-of-consciousness lyrics. In business meetings, Clinton talked in riddles (which were then ‘translated’ by his manager), and once claimed to have a stash of cocaine of such mystical potency that anyone who ingested it would inexplicably start speaking Spanish. “I didn’t understand a word Clinton said,” admitted Larry Harris. “His music was brilliant, but it wasn’t made for hit singles.”

Bogart did everything to make Casablanca stand out: personalised LP catalogue numbers (every one started with NB, after Neil Bogart), band names printed larger on spines so they were more visible in radio station libraries, and merchandise flyers inside Kiss LPs. But as one ex-Casablanca staffer remarked: “If it cost [Neil] three dollars to make two dollars back, he’d do it.”

Within a year, the label’s relationship with Warner Brothers was collapsing. To start with, Warners didn’t like Kiss. Bogart talked label head Mo Ostin into cutting Casablanca loose. But that came at a price: $750,000. Ultimately, what saved Casablanca was Alive!, a double live Kiss album that gave the label its first precious Top 10 hit in the summer of 1975. But Simmons used Alive! as a bargaining tool after discovering Casablanca owed Kiss thousands in unpaid royalties.

“Neil called me in the middle of the night and said, ‘You gotta give me this record.’ And I said, ‘I can’t, you owe us money.’ He got very angry and there were threats made. The truth is, Neil was under pressure. He’d borrowed money from certain people.”

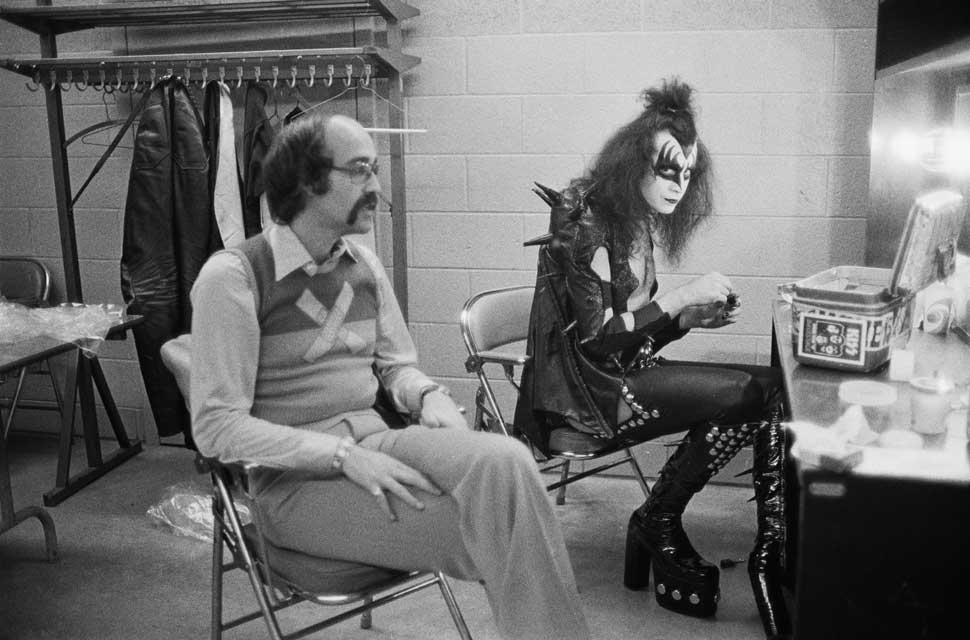

As Larry Harris (pictured below with Gene Simmons) reveals in And Party Every Day, Bogart had Mafia connections. But they were connections he was never comfortable with. So much so that when Bogart was unable to meet Casablanca’s weekly payroll, rather than call in another favour from “certain people”, he flew to Las Vegas, cashed in his line of credit at a Mob-owned casino, paid his staff, and then returned the money before the casino bosses realised what he’d done.

The Casablanca show went on, and was soon bigger than ever. In 1976, the label merged with a Hollywood production company to become Casablanca Records And Filmworks. Their first movie was 1977’s scuba-diving drama The Deep, notable for actor Jacqueline Bisset in a wet T-shirt. Cue another Bogart brainwave: wet T-shirt contests across America.

Fittingly, Casablanca left their modest New York HQ and moved into 8255 Sunset Boulevard, Los Angeles. The new offices mirrored the desert scene depicted on their record labels, complete with palm trees and a stuffed camel in reception.

Bogart and Harris had buzzers under their desks to control entry into their offices. It was a necessary precaution. After all, a drug dealer with bad acne nicknamed ‘Pock Face’ visited the office every week to take their orders. “It all went down on expense reports,” said Harris. “An ounce of weed was ‘A nice steak and a bottle of Bordeaux’.”

So much weed was smoked that the aroma permeated the rest of the building via the air conditioning. Meanwhile, cocaine was routinely snorted off desks, regardless of who was in the office at the time. “Was it worse for drugs at Casablanca than at other record companies?” ponders Gene Simmons. “Yes it was. I never approved of it. But the atmosphere was never mean-spirited, like it was at other companies.”

When Bogart and Harris were too revved up on cocaine, they turned to Quaaludes to bring them down. When they took too many Quaaludes, they crashed out in Harris’s office.

Both would be woken when their promotions manager struck a large gong to celebrate another Casablanca record being added to a radio station playlist. Getting those records added was made easier by plying DJs with drugs and plane tickets. On one Casablanca-funded junket, a New York DJ ended up having drunken sex with a 70-year-old woman while flying first class on a 747. As Bogart said, “The sky’s the limit.”

“Casablanca was exactly what you’d imagine a record company in the 70s being like,” says Angel vocalist Frank DiMino now. “It was extraordinary.”

Bogart had signed Angel as a sort of ‘anti-Kiss’. But where Kiss were four distinct comic-book characters, Angel were five musicians dressed in identical white spandex. Furthermore, their blend of operatic rock and power-pop was a hard sell.

Casablanca tried to break Angel by taking the same approach they’d done with Kiss: everything bigger than everything else. Bogart signed off on a deal to hire Sid and Marty Krofft, who’d co-designed the Haunted Mansion at Disneyland, to build Angel’s stage set. The Kroffts devised an 11-foot, hologram-like replica of the angel Gabriel’s face, as depicted on their debut album cover. Gabriel’s eyes blinked and moved and he even ‘spoke’. The band members would then emerge – or not, if the doors stuck – from cubicles at the back of the stage.

“Can you believe it?” chuckles DiMino. “The trouble is, the show was too big for a support act, and we were forced into headlining before we were ready.”

But Bogart wouldn’t give up. Inspired by the success of Parliament’s Mothership Connection LP, he also agreed to George Clinton’s craziest idea yet: a 100-metre flying saucer called The Mothership that ‘landed’ on stage and had to be housed at a New Jersey air force base when Parliament were off the road.

Kiss were now a platinum-selling act, but neither Parliament nor Angel were doing that sort of business. Something had to change. In 1975, Italian producer Giorgio Moroder played Bogart Donna Summer’s Love To Love You Baby, a disco song he’d produced. Bogart loved it, played it at a party, and noticed that when someone jogged the record and it went back to the beginning, everybody cheered.

Like Gene Simmons before him, Moroder received one of Bogart’s late-night calls, begging him to produce a longer version. The hypnotic, 17-minute mix of Love To Love You Baby became a dance hit, and the original single a No.2 hit in the US pop charts. When Summer showcased the song in a Boston nightclub, Bogart had a cake in her image flown from LA to Boston on two first-class airline seats.

Soon Casablanca were tapping into the disco craze with a slew of 12-inch dance singles, many licensed from European labels. In July ’77, Summer struck gold again with I Feel Love, which went Top 10 around the world. “And now Casablanca was seen as the disco label,” says Simmons.

Resourceful as always, Simmons had Summer sing backing vocals on his 1978 solo album. But Kiss’s simultaneously released solo albums failed to sell as well as their own – or Donna Summer’s – records. Tellingly, their next hit was 1979’s dancefloor monster I Was Made For Lovin’ You.

Forever in Kiss’s shadow, Angel followed a year later with the Giorgio Moroder-produced 20th Century Foxes. It wasn’t a hit. “Disco hurt us even more than Kiss did,” admits DiMino.

Gene Simmons’s description of Casablanca as “a place for rogues and rebels” is precisely what attracted French dance producer Jacques Morali. In 1977, Morali assembled a disco group called Village People. Like Kiss, each member had a distinct character, based on the ‘clone’ look – biker, cop, cowboy, etc – popular in New York’s gay clubs. Morali was impressed by the way Bogart had broken Kiss, and brought his group to Casablanca.

Village People’s singles Y.M.C.A. and In The Navy became worldwide hits in ’78. To celebrate, Bogart sashayed into a music-biz convention dressed as an admiral, with his co-workers in matching sailor suits. There was no better metaphor for disco’s late-70s domination of rock than Angel’s Gregg Giuffria catching a flamboyantly dressed member of a disco act fucking a Casablanca staffer over his desk.

But even disco couldn’t save them in the long run. In 1977, Polygram had acquired a 50 per cent stake in Casablanca. Polygram saw the hits but not the debts Bogart had carefully buried with some imaginative accounting.

By 1979, though, disco was dead; Donna Summer was suing Casablanca; Angel were on the verge of splitting; and even Kiss were losing their pulling power. Arrogance was also creeping in. In 1974, Larry Harris had passed on Rush because he thought they were too ugly. But five years later, and to his great embarrassment, he turned down Bob Dylan’s request for a deal to produce new bands.

When Larry’s neighbour, a Warner Brothers employee, told him about this invention called the compact disc, Harris had a bad feeling. He quit Casablanca in 1980, shortly before Polygram learned they’d lost $220 million on the venture and seized 100 per cent control of the label as payback. Neil Bogart was fired. Casablanca limped on until 1986 before folding.

Bogart bounced back with another new label, Boardwalk Records, but it wasn’t the same. One night, Gene Simmons found himself seated next to Bogart at a charity function: “He’d become very puffy. I didn’t realise he was sick.”

Bogart had been diagnosed with lymphoma and died, aged 39, in May 1982. His last ‘hit’ could have been his epitaph: Joan Jett And The Blackhearts’ I Love Rock’n’Roll.

For Kiss especially, Bogart’s death marked the end of an era. In 1982, they released Creatures Of The Night, their last album with makeup for 15 years. “Conceptually, Kiss stuck out like a sore thumb at Casablanca,” says Simmons. “But we were a family, and it was a happy place to be.”

For Simmons, the story has come full circle. In 2000, the Universal Music Group relaunched the Casablanca imprint. “My daughter Sophie is making music,” he reveals, “and currently in talks with Casablanca. How’s that for an ending?”

The Casablanca legacy endures, then, even if Neil Bogart and his dysfunctional family have all moved on or gone to the great VIP lounge in the sky. For all the booze, drugs and office sex, Casablanca also left their mark on the industry. Kiss rewrote the rules of stadium rock and band merchandising, Parliament’s P-Funk became the bedrock of hip hop, and Donna Summer’s dance anthems inspired the 12-inch single.

“Guys like Neil Bogart and labels like Casablanca don’t come around very often,” says Frank DiMino, almost wistfully. For Angel, Kiss and the rest, the sky really was the limit.

This feature originally appeared in Classic Rock in March 2015.

Five Classic Casablanca Albums That Aren’t By Kiss

T.Rex – Light Of Love (1974)

Glam imp Marc Bolan’s US-only release was actually his UK album Zinc Alloy… with extra tracks. America wasn’t interested.

Fanny – Rock And Roll Survivors (1974)

Bowie loved this Californian all-girl band, featuring Suzi Quatro’s sister Patti, and whose doo-wop-meets-pop single Butter Boy became a big US hit.

Parliament – Mothership Connection (1975)

George Clinton’s mind-boggling funk-rock concept album about a pimp in outer space was the spur for their $100,000 Mothership stage set.

Paul Stanley – Paul Stanley (1978)

Still the cream of the Kiss solo albums, Stanley’s set is full of power-pop rockers and splendidly camp ballads. Hold Me, Touch Me… indeed.

Angel – Sinful (1979)

Angel never stood a chance on the same label as Kiss. Still, their pouty soft rock peaked here with the killer glam-pop of Wild And Hot.