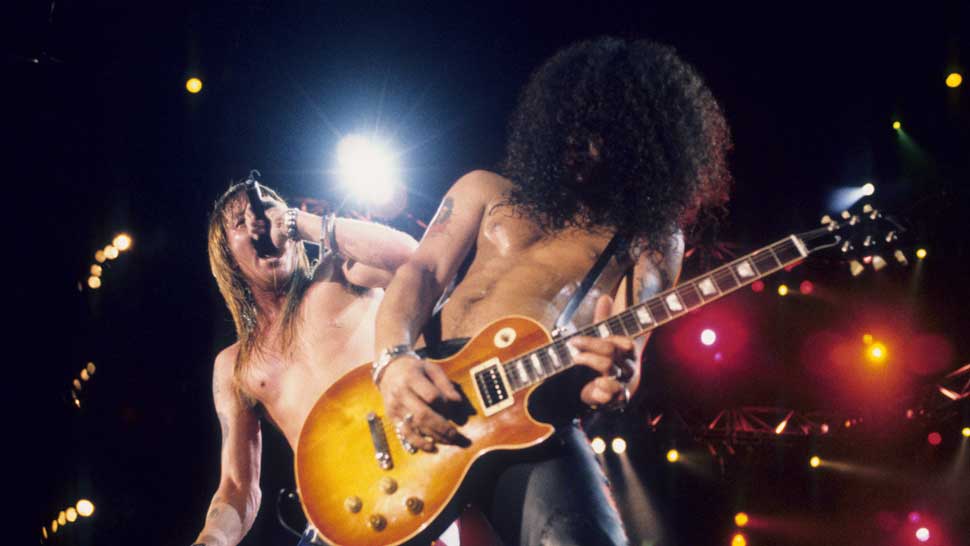

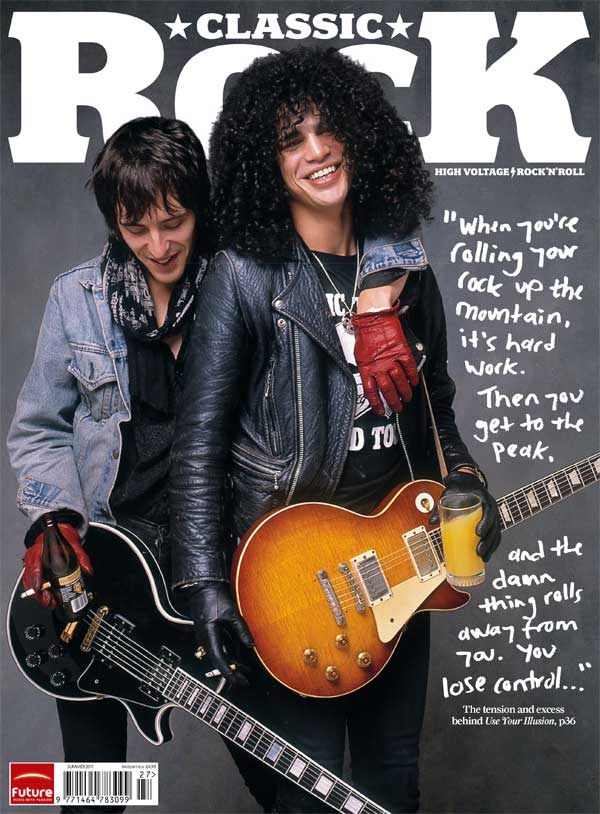

In early 2016, Guns N' Roses made it official: Slash and Duff McKagan were rejoining the band for what would eventually turn into the most lucrative reunion tour of all time. Five years previously, both men – plus original drummer Steven Adler and manager Alan Niven – sat down with Classic Rock to talk about Use Your Illusion, the chaotic project that drove them apart in the first place.

“We got these gigs supporting the Rolling Stones. We’re massive Stones fans, so that’s great for us. We get down there and the Stones each have their own limo, their own trailer, their own lawyer – you know, Mick has one, Keith has one, Charlie has one… I remember turning around to Izzy and saying: ‘Man, we’ll never be like that.’ Of course, six months later, that was us.”

Duff McKagan leans forward in his chair and uses both hands to push his hair back from his forehead. Two decades on, and he’s still somewhat bewildered by the speed with which things unravelled for the five original members of Guns N’ Roses. The last to leave, hanging on heroically until August 1997, he tries hard to reconcile the memories of those early years with the train wreck that was to come.

“You know,” he says, “I’m still not sure that I can tell you exactly what happened, and I was there.”

For a few brief, bright months in 1991 – beginning on the 17th of September at midnight, to be precise – Guns N’ Roses achieved that rare state: they were the biggest band in the world. At that moment, Donald Trump was in a limousine with five models, heading for Tower Records in Manhattan, on his way to buy Use Your Illusion I and II, the new albums that were, in a music industry first, being released simultaneously. Stores in every major city were opening at 12 in order to sell them.

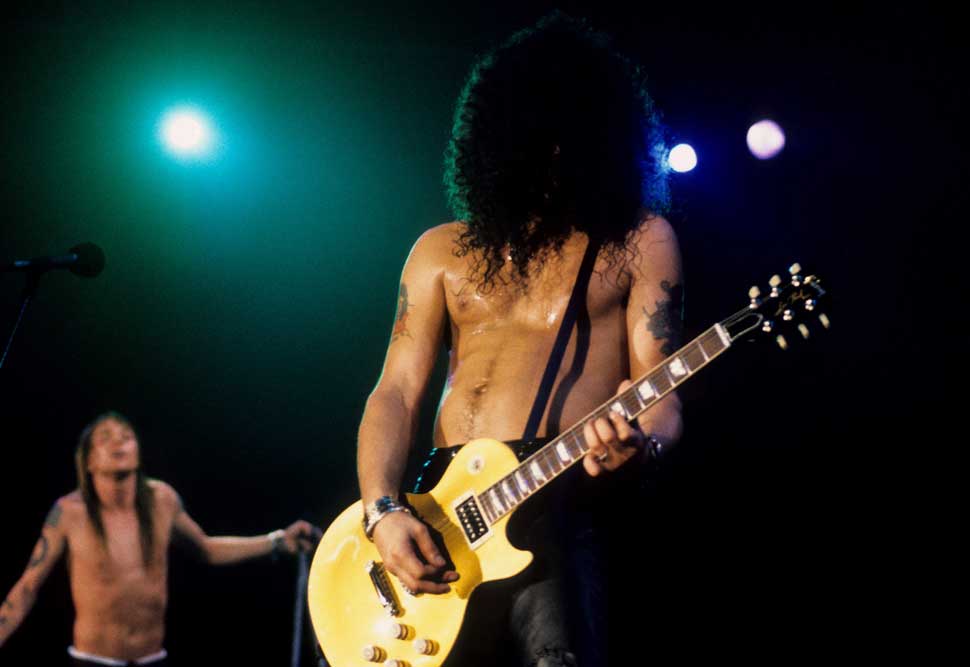

Slash, who was burned out by their creation and about to take a holiday in Tanzania, interrupted his journey to the airport to stop off at Tower on Sunset Boulevard to watch the records go on sale from behind the two-way mirror in the back of the shop, the very same mirror from which store detectives had arrested him for stealing cassettes ten years earlier.

“It was,” he says ruefully, “a magic little moment. Then I took off and went to Africa and got away from it. I went out to the Maasi Mara for a couple of weeks, and that’s about as far removed from ‘rock star’ as you can get.’

When he returned, Use Your Illusion II had sold 770,000 copies and was at No.1 on the US Billboard chart, while Use Your Illusion I had sold another 685,000 and stood at number two.

“Yeah, we had overnight success,” says Alan Niven, the man who managed Guns N’ Roses almost to that point. “It took us three years. The momentum you try and create then creates its own momentum. If you’re Sisyphus and you’re rolling the rock up the side of the mountain it’s hard freaking work. Then you get the rock to the peak of the mountain and suddenly the damn thing rolls away from you. Your labour turns into lost control.”

His control was gone already. He had been fired by Guns N’ Roses months before the albums were released. Just as it would with Slash, Duff, Izzy, Steven and Axl, success was about to extract its price from Alan Niven.

“It put me in a real black pit at one point,” he admits. “It did all of us. Look at what happened. They never made another meaningful record. Izzy was gone three months after I was. It just devolved from that point, because from then on, the shift was between a young up-and-coming band to something that is more recognisable today, which is basically, it’s Axl’s band, and you can be sidemen for as long as I pay you.”

Guns N’ Roses had always been fuck-ups, it was part of their appeal. Tom Zutaut, the young A&R man who’d signed the band to Geffen, was fighting not to have them dropped before they’d even released an album. He’d almost had to beg Alan Niven to take them on as they drifted towards self-immolation. Niven had agreed, in part because “the situation was so fucked up I couldn’t make it worse”.

Niven’s managerial strategy was based on the one that Peter Mensch and Cliff Burnstein had used with Metallica, another uncompromising, hard-sell of a band; underground at first, and then maybe gold with album number two and if they got really lucky, platinum after that.

“Nobody knew it would explode as it did,” says Niven. “Anyone who says they did is certifiable.”

He planned to build a profile in the UK to gain credibility in America. When the band appeared at Donington in 1987, they had sold 7,000 records. A week later, it was 75,000. By the Spring of 1988, Appetite For Destruction had irresistible momentum behind it, and all bets and strategies were off. The results of selling millions and millions of records were disorientating, terrifying even.

“I don’t want to speak on the other guys’ behalf,” says Slash, “but I went from a gypsy troubadour-type kid without anything, through touring with Guns and all those experiences just basically living on the road and never really living anywhere else, and then just sort of thrown into superstardom and not knowing how to handle that. Not having any domestic skills for living at home. Just not knowing which way to turn and not knowing whether I was happy or not. And then pulling into a major drug depression and having to get it all back together to go in and make the second record and being completely disjointed.”

“We all bought our houses and we all had our friends, and our friends would be saying: ‘You’re the glue that holds the band together’,” nods Duff McKagan. “And we’re all getting that. You don’t know what to think. It’s never happened to you before. The record finally broke in the States a year after everywhere else. All of a sudden we came back to LA, and everyone in the clubs, they’re all dressed like us.

"Imagine coming back and you’re a cultural phenomenon. People are dressing like you. Your music is being played on the radio all the time. You walk into a grocery store and you’re on the cover of Rolling Stone, and people see that magazine cover and they see you and they’re freaking out. This is in the grocery store I’ve always gone in…”

Alan Niven didn’t need to be a student of rock’n’roll history to understand what would happen next. He fought fires, and while he did, he bought time with a mini-album, GN’R: Lies.

“One of the things I’m proud of is that at least none of the band members died on my watch,” he says, his voice slower now. “That took a lot of effort. The bottom line is, you have to help them fight the battle, but only they can win the war. Slash went cold turkey in my home one time. I cleaned the vomit from his mouth, made sure he got clean. Then as soon as he’s clean, he calls a car and goes straight to his dealer.

"That was the sort of thing you were dealing with. You’d call Slash, say: ‘Come into the office, you’ve got an interview with Guitar Player magazine’. There was no interview. He’d come in and you’d stick him in a car, fly him off to Hawaii and put him on a golf course where he couldn’t score. We’d do that sort of thing.

“I put Steven on a plane one night to go to Hawaii, and he’s sitting in first class yelling: ‘We’re all going to fucking die… the plane’s going to fucking crash…’ Of course, they invite Mr Adler to exit the plane at that point, and so he’s back into LA and he can get to his dealer and his dealer can get to him and we’re fucked all over again.”

Bands exist as delicate ecosystems. Change in one part can affect others in unexpected and unpredictable ways. As Steven Adler has argued long and hard in recent years, GN’R and Appetite For Destruction had something unique, a rough magic that rose up from its constituent parts. “The five of us, we’re brothers,” he says, even now. “And what do brothers do? They fight.”

Guns N’ Roses were fuck-ups, and the biggest fuck-up in Guns N’ Roses was Steven. “He was suffering the worst and couldn’t pull it back,” says Duff, who remains in contact with the drummer. “We had this unwritten sort of code – pull it back when it’s sensible, when it’s time to record or time to play a show. Pull it back. Check yourself. There had been a few times where we’d check each other. You know: ‘hey dude…’ And that’s all you’d have to say. It was a sort of honour amongst thieves.

"But Steven wasn’t able to pull it back time and time again. The irony wasn’t lost, even then. Slash and I told him quite a few times: ‘Dude, it’s us talking to you. If we’re telling you you’re getting too fucked up, you’re getting too fucked up. Look who’s talking to you. We’re the guys that everyone else is worried about, and we’re worried about you.’ It was really heartbreaking. We warned him too many times.”

“It was totally regrettable,” says Slash. “But the band finally got to the place where we wanted to make a record, which was a hard enough place to get to… We’re talking about the span of about a year, which to us was like a lifetime, and Steven… we could not get him back to front. We were resigned to the fact that he wasn’t going to be able to do it in the time frame that we needed to get going, because we might miss the bus. We might fall apart again and take another year to get it together.”

In the summer of 1990, the window seemed to be open. But every time Adler went to the studio, he blew it – too drunk, too stoned to function. The band had a lawyer draw up a legal document informing him that he would be fired. They thought it would scare him but it had little effect. “All the way up to getting Matt Sorum to play on the record, we thought that would get Steven back,” says Duff. “Then we realised, it’s just not going to happen. It’s just not. I wouldn’t be being honest if I told you I knew exactly the point.”

“In no way was it minor,” says Alan Niven. “Firing a member of a band is a pain in the ass. It was incredibly painful and frustrating. I’ve got to confess I’m still capable of a flash of red hot anger with Steven at that.”

Adler’s own recollections of the moment are fractured, perhaps understandably given the state he was in. “Man, I was fucked up, and I have never denied that, I couldn’t really deny it because it was pretty fuckin’ obvious…” he says. “But I wasn’t the only one. I remember one day Slash called me to go to the studio and play Civil War, I think it was. I’d been given an opiate blocker by a doctor. I still had opiates in my system and it made me so sick. I must have tried, like, 20 times to play it, but I couldn’t. I was very weak and I didn’t have my timing. Slash and Duff were shouting at me and telling me I was fucked up.

“I got a call a few weeks after that and I had to go to the office and there was all these stacks of papers, contracts, for me to sign, and I realised that I was being fired. It ended up with me having to go to court to get my royalties and my writing credits.” [In 1993, Adler was awarded a reported $2.25m in an out-of-court settlement for his contribution to the band prior to Use Your Illusion. He does not have any writing credits on UYI].

Adler was sacked by Guns N’ Roses on July 11, 1990 ostensibly for being unable, through drink and drugs, to fulfil his duties. Yet for many years, a rumour has circulated that it was an incident in which Axl Rose’s wife, Erin Everly, OD-ed at Adler’s house that soured his relationship with Axl. In a 1992 interview, Rose claimed that Everly had been found ‘naked’, and was taken to the emergency room.

“I had to spend a night with her in an intensive care unit because her heart had stopped, thanks to Steven,” he said. “She was hysterical and he shot her up with a speedball. She had never done jack shit as far as drugs go, and he shoots her up with a mixture of heroin and cocaine?”

In a 2006 interview with the Metal Sludge website, Adler denied giving Everly drugs, claiming that he was jamming in his house with Hanoi Rocks guitarist Andy McCoy when McCoy’s wife turned up with an already intoxicated Everly: “I called the ambulance and saved her,” claimed Adler, “[and] this bitch [McCoy’s wife] tells Axl I gave her heroin. He calls me up and says he’s coming over with a shotgun to kill me…”

“I kept myself from doing anything to him,” Axl told Del James in ’92. “I kept the man from being killed by members of her family. I saved him from having to go to court, because her mother wanted him held responsible for his actions.”

“Axl was fucking convinced that Erin had been overdosed,” says Niven today. “Well that’s going to go down well, isn’t it? That really helped everybody. Is it any surprise we got to the point that we had to seriously consider getting someone else?”

With Steven Adler went that ecosystem. Other drummers could drum, but they couldn’t drum like Steven. “Let me say this,” adds Niven. “Steven is not the world’s best drummer by any stretch. Duff even had to show him what to play sometimes. But he had a quality that he brought to the band that anybody would accept as being part of the magic. He had such an enthusiasm for what he was doing.

"Matt is a competent drummer but he can’t replicate that. He has a great consistency but he also has a heavy hand. He cannot match the feel that Steven had. So did we want Steven to go? Fuck no.”

Izzy Stradlin, whose gloriously offhand guitar playing itself lent such groove to the music of Guns N’ Roses, also felt Adler’s absence diminished the band: “[It was] a big musical difference,” he told Musician in 1992. “The first time I realized what Steve did for the band was when he broke his hand in Michigan [in 1987]. Tried to punch through a wall and busted his hand. So we had Fred Coury come in from Cinderella for the Houston show. Fred played technically good and steady, but the songs sounded just awful. They were written with Steve playing the drums and his sense of swing was the push and pull that give the songs their feel. When that was gone, it was just… unbelievable, weird. Nothing worked…”

Adler’s replacement, Matt Sorum, was no stranger to a little chemical enhancement himself, as he told Mick Wall: “Here I was replacing the drug addict drummer, right? But he did heroin and I had cocaine.” Nonetheless, Sorum had control of his lifestyle. It is only in the last two years that Steven Adler has been able to acknowledge that he did not, and that his failings had played a role in his dismissal. It’s a process that began with an appearance on a reality TV show, Celebrity Rehab With Dr Drew, in 2008.

“I blamed Slash and Duff and Izzy and Axl for my downfall for a lot of years, but when I started working with Dr Drew Pinsky, I learned that I got to talk about these things and get them out of my system,” Adler says. “I needed to apologise to Slash for blaming him for everything that happened to me. Once I did that, it was like this huge weight lifted off my body… Now I can move on.”

“Looking back,” says Slash. “I think that losing Steven was one of the major components in the disintegration of the original band, but I think that was more Axl anyway. Steven was just the tip of the iceberg.”

One thing that Guns N’ Roses always had was music. They may have been stoned, but they were not standing still. Unlike many second records, material was not a problem. November Rain, perhaps the pivotal song on Use Your Illusion, pre-dated Axl joining the band. A 20-minute acoustic demo of the tune was recorded very early on at Sound City in Los Angeles. Don’t Cry was, Axl remembered, the first song the band ever wrote together, a song about a girlfriend of Izzy’s: “I was really attracted to her. They split and I was sitting outside the Roxy, and you know, I was like really in love with this person, and she was realising this wasn’t going to work, she was telling me goodbye. We wrote it in about five minutes.”

Alan Niven had insisted that some material from the Appetite For Destruction sessions be held over: included in that was You Could Be Mine, Back Off Bitch, Bad Obsession and The Garden. In addition, Slash, Izzy and Duff were all prolific, and fast, writers.

“It was so splintered and such a struggle but I remember we finally got together after just a major rollercoaster ride of ups and downs,” says Slash. “It was at my house on Walnut Drive in the Laurel Canyon hills. We compiled 30 fucking songs, more than 30 songs, in one evening. That was the one time in all of it that I remember that the band felt like itself. Just the guys like I was always used to – Izzy, Duff and Axl. We managed to put a focus on 36 songs. That was the only group writing session we had where we were all together in one room. That was a very poignant moment.

"The next thing you know we were looking for drummers. I remembered seeing Matt with The Cult and thinking that he was the only good drummer I’d seen, and calling him and having him come down. We started rehearsing this material and next thing you know we’re in the studio. Getting the basic tracks together so that we could play them front to back actually happened really quickly. But that’s a hell of a lot of material and it was an epic journey.”

Slash had an 18-minute song, Coma, that he had written: “while I was completely stoned”. Duff had So Fine and Izzy had his usual raft of drop-dead cool rock’n’roll songs: Pretty Tied Up, Double Talkin’ Jive, You Ain’t The First, 14 Years and Dust N’ Bones.

“And,” Slash remembers, “there were other songs that Axl had, that I had never heard before. Songs that he had written with West Arkeen, back in the day.” Arkeen, a wild character of the sort you only seemed to get back in the 1980s who died of an overdose in 1997, had a co-credit on The Garden, Bad Obsession and Yesterdays, as well as It’s So Easy from Appetite For Destruction. Axl’s friend Del James also received a credit on Yesterdays and The Garden.

“I was good friends with West, but I never wrote with him,” says Slash. “We hung out and jammed a couple of times but there was only a couple of songs I was ever around where I was there with Axl and we were all playing together. West and Axl and Del and Duff, that was more what that was like. I didn’t mind. As long as the song was good and I could do something with it.

"I remember It’s So Easy being one of those songs that when I first heard in its original form I was like, ‘whatever’, but then I got to it and changed it to what it sounds more like now. I remember The Garden being really good. But no, I didn’t mind too much. I was usually too preoccupied doing whatever debauched shit I was doing. If everybody was busy doing that, nobody was looking over my shoulder while I was doing what I was doing.”

Although the band’s existence was precarious, their situation remained extraordinary. Appetite… continued to sell in its millions, and the non-appearance of its follow-up gave Alan Niven leverage to do things that had never been done before. Success in the music business, like success in most businesses, is built on having something that someone else wants.

“I’m getting a lot of pressure from an individual called David Geffen, saying: ‘When am I going to get my fucking record?’” says Niven. “His agenda was that he wanted to release the record before selling DGC so that he could benefit from the sale of the record and then sell his company. Then when you estimate that we were figuring Use Your Illusion would probably do about a hundred million dollars in worldwide commerce in the first week gross, you can imagine there’s a certain amount of pressure. David does have his reputation.”

Regardless of that, Niven decided that he wanted to renegotiate the band’s contract with Geffen. He’d been told that the managements of both Whitesnake and Aerosmith had tried their luck after selling five million records each, and had been turned down flat. David Geffen was notoriously hard-nosed, but then so was Niven. The undelivered Use Your Illusion was his weapon, his nuclear option. At a dinner with Geffen’s label president Eddie Rosenblatt, he pressed the button.

“After I’d made sure that Eddie had had at least half a dozen glasses of wine, I leaned over to him and said: ‘I hate to spoilt the evening and don’t freak out on me now, but you need to take a message to David, and that is until you renegotiate there will be no record’.” Niven got his deal. In return, he delivered an elegant and lucrative solution to the abundance of material that Guns N’ Roses had written.

Instead of being a double album, the kind of bloated artistic and commercial proposition that had stalled and even sunk careers, Use Your Illusion would come as two single, standalone records, released on the same day. It was a classic music business masterstroke that allowed the band to claim it as an altruistic gesture to their fans, while providing not one but two revenue streams for everyone involved.

“We had a huge cloud to get out from under and that was the incredible sales of Appetite,” Niven says. “I was very nervous of a situation where we might sell two million double albums, having sold at that point something like 12 million on Appetite. I had a meeting with Rosenblatt, and he pushed a pencil and a piece of paper at me and said, ‘Write down what you think we’re going to do’. Believe it or not, I wrote down that I thought we’d do four million of each single album, which meant we could say we’d sold eight million albums. That, I thought, would have a sense of continuity as opposed to drop-off.”

What Niven and the band also gained was a sense of scale, an idea that Use Your Illusion was more than just a record (or rather two), it was an event, a statement. It set an already singular band further apart. Along with the changing line-up and the new scope of the music, the band’s aesthetic was shifting too. Out were late 80s stylings like skulls and bones and guns and crucifixes, a visual language that anchored the band to a certain time and place. In came something far more worthy of them: art.

Axl Rose had become enthused by Mark Kostabi, a controversial New Yorker who’d taken Andy Warhol’s idea of an art factory to a new level, opening a studio called Kostabi World and having teams of ‘assistants’ turn out thousands of paintings. “Axl really fell in love with his work,” says Niven. “But the thing about Mark Kostabi was that he was playing the art bullshit game. He had other people paint basic backgrounds and then he stole images from classic paintings and stuck them on the backgrounds. Axl loved his conceit, loved what he was doing and bought these paintings that he wanted to use for the covers. And paid a fortune for them.”

The Use Your Illusion sleeves were based on a detail from Raphael’s painting The School Of Athens, a priceless Renaissance masterpiece that hangs in the Vatican. It was completed in 1511, which, as Niven swiftly realised, meant that it was out of copyright by several centuries.

“I’m looking at it and thinking, ‘Great – when it comes to the merchandising, we don’t have to pay Kostabi or anybody else a dime: these things are in the public domain’,” says Niven. “Those images that Axl paid a huge fortune for, he could have basically had for free. It always made me smile to think of Axl writing a huge cheque to this guy Kostabi when he could have had Del James paint similar backgrounds, cut out the same image, stick it on and give Del a six pack.”

Although the final album credits acknowledge a span of two years and seven recording studios, one of the most remarkable elements of the Use Your Illusion set is the speed at which they were recorded in their basic form.

“I was really happy with a lot of the material and I think we went in to do basic tracks and with a new drummer we did 36 songs in 36 days, so we weren’t fucking around,” says Slash. “After the basic tracks were done, I’d spend three weeks doing guitars, which for 30 songs was actually pretty fast. I was sometimes doing two songs in one day. But everything hit a brick wall when it came to doing the synthesizer stuff, and I never agreed with doing the synthesizer stuff anyway.

"Although I think some of it is brilliant, it was part of the new way, which was the beginning of the end. That was the beginning of the whole process taking forever. It was like a lot of days were not working, some days it was working, and most of the record was finished. It didn’t really need all the rest of it. That was the biggest disagreement for me.”

Izzy Stradlin was also exiling himself, distanced by the scale of the recording. “I did the basic tracks, then he [Slash] did his tracks, like a month or two by himself,” he said. “Then came Axl’s vocal parts. I went back to Indiana…”

“Well Axl’s a… perfectionist,” says Duff slowly. “That’s what makes him great. The end product’s great, but it gets maddening to work with that person. There’s no hashing out with them. November Rain in particular, the song was torturing him. He was happy he was finally finished with it. It wasn’t really characteristic of the band.”

“Axl had this vision he was going to create,” Matt Sorum told Mick Wall. “We’d start at noon, the work ethic was cool. There was a lot of alcohol around, but the heroin thing had definitely subsided at that point – Slash had quit, Izzy had quit. We were dabbling in cocaine and partying rituals… But it was never really cool to do a lot of drugs in front of Axl.”

But as the sessions became more drawn out and splintered, “It was later nights,” says Sorum. “We’d start at six or seven. Axl would want to do November Rain and Don’t Cry, his songs.”

Hindsight is a beautiful thing. It is tempting to look back at the records through the prism of the band’s impending devolution and see Axl Rose taking control and exacting his revenge on the world, living out all of the rock star fantasies he had as a boy in Indiana. The truth was more complex.

“When he was younger, he played piano and composed on piano,” says Alan Niven. “I’d lay a bet that a record like Elton John’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road and songs like Funeral For A Friend had a huge impact on him. He aspired to that level, and anybody who has a hero and aspires to match a hero also in their heart hopes to exceed their hero and validate their presence.”

So Use Your Illusion had November Rain and Estranged; big, ambitious pieces with themes that hinted at Rose’s obsessive nature: November Rain is a song about “having to deal with unrequited love”, he said. “Estranged is acknowledging it and being there. And having to figure out what to fucking do, it’s like being catapulted out into the universe and having no choice about it and having to figure out what the fuck are you gonna do because the things you wanted and worked for just cannot happen.”

Yet their grandeur was counterpointed by shorter, more violent tunes like Get In The Ring, Right Next Door To Hell and Back Off Bitch, songs that sought to settle explicit scores and that made no secret of the depths of rage that fuelled their writer. It was an area in which he already had form.

“I thought they were tiresome, small-minded and mean,” says Alan Niven. “I’d already been through One In A Million with him. But with the meanness and the vitriol – if you’re going to apply it, apply it to something big. He’d make his attacks on his next door neighbour or journalists, and I’m thinking, ‘Axl, this is the scope of your world?’”

Rose addressed such accusations directly in 1992: “Back Off Bitch is a 10-year-old song,” he said. “I’ve been doing a lot of work and found out I’ve had a lot of hatred for women. Basically, I’ve been rejected by my mother since I was a baby. She’s picked my stepfather over me ever since he was around and watched me get beaten by him. She stood back most of the time. Unless it got too bad, and then she’d come and hold you afterward. She wasn’t there for me. My grandmother had a problem with men. I’ve gone back and done the work and found out I overheard my grandma going off on men when I was four. And I’ve had problems with my own masculinity because of that. So I wrote about my feelings in the songs.”

Use Your Illusion I and II became records that said plenty about their time: they are indulgent, bloated and created by men who weren’t hearing the word ‘no’ too often. And yet they are also unafraid and unapologetic and contain some of the best work GN’R ever produced. Interestingly, too, they lend perspective to the band’s two other major releases: a clear line can be drawn through them from Appetite For Destruction to Chinese Democracy.

Bitter, raunchy little rockers appear alongside romantic ballads, Izzy Stradlin’s loose and groovy riffs sit with Slash’s heroic piledrivers, Axl’s bleeding heart is on his sleeve one minute and being rammed down your throat the next.

“We knew we had to bury Appetite in some way,” Rose told Hit Parader, soon after their release. “There was no way to out-do that album, and if we didn’t outdo Appetite in one way or another it was going to take away from our success and the amount of power we had gained to do what we wanted. I’ve never really looked at it as two separate albums. I’ve always looked at it as an entire package. For me it fits together perfectly for the 30 songs in a row. Everything that we decided to record for the album made it.”

The records ran over one more bump in the road before they were done. Bob Clearmountain was hired to mix the tracks that Mike Clink had engineered. “Basically Axl moves into the studio with him, and God knows what that was like for Bob,” says Niven. “Mr control freak breathing down the back of your neck. Bob Clearmountain was one of my heroes, but the mixes had no life and vitality.”

Tom Zutaut suggested that Bill Price, who had almost produced Appetite For Destruction when the band had planned to record it in London, should try out for the job. Price delivered a “loud, in-your-face, heavily compressed” mix of Right Next Door To Hell as an audition piece, and got the gig.

“It was a very long process,” Price recalled. “The last half a dozen songs were recorded, overdubbed, vocal’ed and guitar’ed, what have you’ed, in random recording studios dotted about America when they had a day off between gigs because the tour had already started. My mixing mode then switched into flying around America with pocketfuls of DATs, playing it to the band backstage.”

“I never sit down and listen to records once they’re finished, so it’s been so long since I heard them,” says Slash. “In hindsight I can look back and think about things I disagreed with and this that and the other, but at the time, I was just so gung-ho to finally be productive and to have the whole band in some sort of state of harmony. But to this day I have always thought that, for me as a guitar player, it was a fun canvas to play on and I felt I played really well on those records. I was enjoying myself. Three weeks with Mike Clink playing guitars, that was a fucking blast.”

Alan Niven can still remember the long, lost weekend with Slash when he understood that things had changed. That delicate ecosystem that Steven Adler somehow had a part in maintaining was gone. When a butterfly flaps its wings on one side of the world…

“We make choices every day. With Use Your Illusion, Slash made a choice and I totally understood it, and to this day I don’t agree with it. One night, he and I were sitting alone in his house up in Laurel Canyon and he was really bemoaning what he thought Axl was doing to the band, and he was doing it in the context of the material he was writing. He felt it wasn’t Guns N’ Roses, he felt that he was being compromised by having to apply himself to it. He felt that one song of that kind of epic style might be appropriate, but so many?

"I looked at him and said: ‘You’ve got to express this’. And Slash looked at me and he said: ‘Listen, my father [an artist who designed album sleeves] has got a cupboard full of gold records, and he hasn’t got a pot to piss in.’ And that’s where he folded. From then on, Axl was in charge.”

Slash’s response is measured, guarded: “Well…” he says slowly, “I think that Axl’s always been difficult, but we managed. Because of the five individuals, and Alan, and Tom Zutaut, we managed to make it work. So you lose Steven, and then the Alan thing… I backed Alan all the way up to a certain point and then he did actually do something that set me off and I said: ‘I can’t fight for you any more’. But that was a volatile situation that was going to explode at some point.

"Alan wasn’t going to take Axl’s shit and Axl could not stand that, so it was a battle. I think in hindsight, although it wouldn’t have been any fun, but all we could have done differently was just to refuse Axl everything that he ever wanted. I don’t think it would have been very productive, but all things considered, what we ended up doing was going along with a lot of stuff just in order to be able to continue on, which built a monster.

"All I can see happening is that nothing would have happened, because it would have been at a standstill. I think we probably would have broken up a lot sooner. But I can’t support hiring Doug Goldstein as a manager. I knew that he was a creep from day one.”

As the records were being mixed by Bill Price, Rose called Niven and told him that he could no longer work with him. “It’s pretty plain when the first thing that’s done after I’m fired is that the name is taken away from the rest of the band members [Rose demanded and gained legal ownership in the early 90s],” says Niven. “That tells you an awful lot right there. It was basically people taking control. Axl had an enabler and off they went. Doug Goldstein was a security guy when I took him on. Well credit where credit is due, one of the things that Doug was golden at was clean-up.

“Three months after I’m gone, Izzy quietly packs his bags, because it’s not the band any more, it’s not the band that he could feel any more. The feel of Izzy is something I profoundly connected to. For me he was the heart – and let me choose my words carefully – because he was not the heart and soul of the band, but he was the heart of the soul.”

“Alan was somebody that I trusted, whereas I knew Doug was somebody that played both sides against the middle,” says Slash. “In other words, he’s telling me one thing, telling Axl another and appeasing Axl all the time. And I was aware of it, but at the same time, as long as shit was getting done I was okay. As long as we kept booking tours and I was sort of kept in the mix as far as the mechanics, that’s how we managed to get from 1990 to 1990-whatever.

"We had the world record for touring. Even when we lost Izzy because we had all those shows booked, I was just like, ‘Let’s keep going’. But when the tour was finally over and it was time to get back to work, it was impossible, because Izzy wasn’t there, Steven wasn’t there, and it really dawned on me – the harsh reality that Axl and I had grown so far apart and we weren’t really all that close to begin with. We’d grown so far apart, and to this day, there’s no putting that back together.”

Rose, of course, saw things differently. In one of his rare utterances on the subject, he told Rolling Stone: “It was a king-of-the-mountain thing. It’s an old saying: ‘Don’t buy a car with your friends’. The old band all wanted to hold the wheel and ended up nearly driving the car over a cliff.”

Duff McKagan was making one of his periodic trips to London. It was October 2010, and he was in a hurry. He came in on the red-eye and went straight to his usual hotel, where the manager had booked out a meeting room for him. He had three in a row, all sober business planning stuff, the boring meetings that he’d learned he had to take if he wanted life to run smoothly. The Use Your Illusion experience had taught him that, and more.

Before he’d even put down his bags, the hotel manager said to him, ‘So you’re playing tonight?’

“Am I?” he’d replied absentmindedly, thinking to himself: ‘Man, you know why I’m here, you booked the meeting room for me,’ and then he’d picked up his key, taken the lift to his suite and put some music on, loud enough to shake the jetlag. Next thing he knew, there was an angry guy from the next suite along at his door complaining and when he looked up he realised that the angry guy at the door was Axl Rose. They hadn’t played together for 13 years.

“For me as a grown up man who looks at life the way I do, it was meant to be,” says Duff. “We had a grand old time. We went down to the gig together. I was tired by that point. I was drinking Red Bull so I was half out of my mind. Next thing I know I was playing. It was odd when I looked out in the crowd. I’m like: ‘Oh, I’m going to have to explain this in every interview I do now…’

“Axl’s way of rationalising things is sometimes the most genius thing ever and I’ve always liked that about him. Other things were maddening, and I’m sure I maddened him. On the Illusions tour I could have not gotten so fucked up all the time. Did I blame it on him for being late all the time? Yeah, for the longest time. But you gotta start taking responsibility for yourself and that’s what I didn’t do.

"I knew there were times I could have pulled up and been a real voice of reason, because I think I was looked at as a voice of reason I that band. I didn’t know how to and I didn’t do it, but at least in my lifetime I have come to terms with it. I think the path of that band happened the only way it could have happened. It was fucked up from the beginning, it was beautiful and fucked up.”

Duff McKagan remains the link between the original five members of the band. Although he doesn’t want to discuss his relationship with Axl, such as it is [“that’s personal”], he enjoyed spending time with him in London. A few months later, he jammed with Steven Adler at the Borderline, an event that, it’s safe to say, flew a little more under the radar than the appearance with Guns N’ Roses. And he is close to Izzy, too.

“He has a cool fuckin’ life man,” Duff says. “I remember when he got sober, I was watching him. Early 90s, while we were still on the road. And the moment that he became at peace with himself, was the moment I also recognised he’s not going to be here very much longer. He’s a great guy and a very positive influence in my other life.”

The sales of Use Your Illusion I and II stand today at more than 15 million copies, almost double the estimate that Alan Niven made to Eddie Rosenblatt. The subsequent tour, which stretched on for years, grossed millions of dollars more.

The price was less easy to quantify. Alan Niven moved to Arizona and withdrew from the music business until very recently. Izzy Stradlin remains to all intents and purposes, retired. It took W Axl Rose 17 years and 11 band members to produce another Guns N’ Roses record. And Guns N’ Roses is still the name most readily attached to the careers of Slash and Duff.

“I’ve wasted 20 years doing drugs,” says Steven Adler, “but I have a new start now and I’m taking it for all it’s worth. My book showed all my warts and scars. It’s something for me to make amends to everybody, for all the bullshit in my life.”

“Most people go through life saying: ‘I wonder what it’s like to get to the apex of your occupation?’” says Alan Niven. “A lot of people spend their lives worrying about anonymity. But when you get to the apex, you find out it’s a fucking illusion, it doesn’t exist. And when your anonymity is compromised, you find out its value. The toll came later and when it did come it hit hard. I went through the severest depression you can go into.”

“You know,” says Slash, “when I look back on it, it was a monumental achievement. The first thing I think of when I think of those albums is that it was such a whirlwind of shit was happening at that particular time, but it was a huge accomplishment. I think the Use Your Illusion records, if you know the backstory, were very victorious.” He pauses, while he thinks of one more thing he wants to say. “After all of it, we came through. Don’t put too much of a negative spin on it, man…”

“That record polarized people. I’ve come to understand that, and I’ve come to be at peace with the whole thing,” says Duff as he prepares to catch yet another plane, this time back home to Seattle. “I only figured this out a year ago. ‘When are you guys gonna get back together?’ Well, none of us guys have said we’re going to. I wonder if some people – not all – if some people think if we got back together, they’d get their teenage years back? Are they asking us to get back together so that they can get their youth back, even for a minute? The title of the record, it’s fuckin’ appropriate when you think about it…”

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock 160, published in the summer of 2011.