"Their music was about us, about you, about the big wide world that waited": Every studio album by The Clash ranked from worst to best

Want to know the best albums by The Clash? And the worst? Here is the ultimate guide

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

Most exciting rock’n’roll is made by people in their 20s for people in their teens. It’s like a note slid under our bedroom doors by our big brothers and sisters that says everything will be alright: we will get laid, we will fall in love, we will get high, our parents won’t rule our lives forever. The Clash gave us all that – and then so much more.

Because while they were in love with the rock’n’roll whoa – and made music for people with Ford Cortinas and dead-end jobs – London Calling, Sandinista! and Combat Rock are albums for grown-ups, albums you take with you after the anger subsides, when you start being less self-obsessed and begin to look out into the world.

Most rock’n’roll is solipsistic and inwards-looking – but from London Calling onwards, The Clash looked outwards. Their music wasn’t about how deep they were or how troubled, how wasted they were on drugs or the pressures of fame. It was about us, about you, about the big wide world that waited for you.

Musically and lyrically, The Clash refused to be “little Englanders”, embracing a world beyond their roots, drawing on rock’n’roll, reggae, calypso, jazz, folk, blues, soul, and sometimes bolting them together (or taking them apart) with a genre-busting experimentalism that they rarely get any credit for. Below, then, are their six studio albums, rated from worst to life-changing first.

NB: The Clash’s back catalogue is a bit of a mess, to be honest. Want to buy the album with I Fought The Law on it? There isn’t one. Heard that (White Man) In Hammersmith Palais is considered by many to be their greatest song? It’s not on a studio album either. Neither are stone-cold classics Complete Control or Clash City Rockers, or relative hits Bankrobber or This Is Radio Clash.

If you want the full picture, you’ll need to get a best-of. For serious fans, that would be the Clash On Broadway box set or the newer Sound System box set. For newbies, The Essential Clash is a good CD introduction (on vinyl, try and find The Story of The Clash Vol. 1 – there is no Volume 2) or 2013's 2CD/3 x vinyl set Hits Back, with a tracklisting based on one of Strummer's setlists from 1982.

Cut The Crap (1985)

You can trust Louder

If there was any justice in the world, right now, somewhere on a street corner in England someone would be holding Bernie Rhodes by the collar and kicking him repeatedly up the arse for what he did to Cut The Crap.

From the electric drums and synthetic horns of Dictator, its over-crowded dogs-dinner of an opener, the band’s last studio album is a chaotic, phoney jumble – and such a stain on The Clash’s name that, apart from anthemic single This Is England which appeared on 2005 best of The Essential Clash, it is rarely even acknowledged by the band themselves. (Official band documentary, Westway To The World, doesn’t mention it, choosing instead to pretend the band finished with the sacking of Mick Jones.)

It’s the only Clash album not to feature Jones and, boy, is he missed. With the Strummer-Jones writing credit now laughably transformed into Strummer-Rhodes (manager Bernie Rhodes, who was also in the production seat, credited as Jose Unidos), the balance between Jones’s ear for a melody and Strummer’s lyrical voice was a thing of the past.

Mick Jones had been the heart of the Clash – providing the emotion, the yearning, the melody, the groove – and without him, the band were reduced to a two-dimensional mess, a relic desperately trying to stay angry and relevant. Cut The Crap is left with the humourless, hectoring, slightly embarrassing side of The Clash, Strummer trying too hard to play the role of the angry punk, complete with mohican to help him get into character.

The band’s frontman was lost throughout this period, unable to connect with his new band members, guilt-laden at sacking Topper and Mick, and struggling to deal with the deaths of his parents. Sensing his weakness, Rhodes stepped in – Malcolm McLaren was making music, why couldn’t he? – and took over production duties.

The result is an over-cooked pile of sonic spaghetti. Imagine Swing Out Sister produced by The Exploited and you’ll get some idea of the combination of yobbish terrace chant and soulless 80s production values. When Strummer heard it he flew to the Bahamas and begged Mick Jones – then recording the game-changing This Is Big Audio Dynamite – to rejoin The Clash. Jones, enjoying his freedom, laughed him off. You would’ve too.

Unable to stop it or fix it, Cut The Crap came out, unloved by the people who’d made it. It was shameful – and a shame. Bootlegs from the time caught a band on fire and show that some of the songs (Dictator, Are You Red…Y, Cool Under Heat) actually stand up. Rhodes doesn’t quite ruin the wistful protest song North And South – in the hands of Combat Rock producer Glyn Johns, say, it could have been a keeper – but really only This Is England survived Bernie’s cack-handed, cloth-eared skills at the desk. (In 2020, a fan who hated it so much, took it to bits and 're-recorded' it.)

The things that made This Is England seem pedestrian and cliched when it came out (the effects-heavy guitar sound, the terrace chorus, the lyric straining to make a big statement) somehow now give it classic status. 30 years on, it doesn’t seem as dumbly-obvious but more of a snapshot of Thatcher’s Britain, a dying gasp of protest as unemployment soared and the miners got crushed. It was The Clash’s last gasp too – a bitterly ironic anthem about the betrayal of a country, a nation failed by its leaders and turning on itself – a bit like The Clash themselves.

Combat Rock (1982)

It’s easy to damn Combat Rock with faint praise. It was intended as a double album but after the commercial failure of Sandinista!, CBS brought in Glyn Jones and the editing process began. Trimmed to 12 tracks and powered by two hit singles (Topper Headon’s Rock The Casbah – No.6 in the US – and Mick Jones’s Should I Stay Or Should I Go, top 20 in both US and UK), it became the band’s best-selling album.

So, yeah, it’s ‘the commercial album’ – the one for fair-weather fans. But as hit albums go, it’s pretty fucking weird. For starters it opens with ‘a public service announcement – with guitars’: Know Your Rights, a song without melody or a chorus, that suggests we only have three fundamental rights – and they’re all a bag of shit too. (How did that sentiment go down in Titfuck, Texas?)

Elsewhere, Red Angel Dragnet lets tone-deaf bassist Paul Simonon loose on vocals for a demented Taxi-Driver-inspired punk funk patience-tester while Allen Ginsberg intones random bollocks/garbled poetry over Ghetto Defendant.

When it comes to crowd-pleasing commerciality, it’s fair to say that Combat Rock is not exactly Bat Out Of Hell.

Even at its straightest – on Car Jamming, Inoculated City and Atom Tan – the band sound like they’re dicking around. And while each of those songs could be described as whimsical and throwaway, the sheer fun they’re having is infectious.

And then there’s the hits. Should I Stay Or Should I Go? commits several punk rock crimes:

i) It was a hit.

ii) It really is The Clash finally turning into the Stones, just like all their critics said they would.

iii) It’s a love/heartbreak song. You know: one of those songs they said they’d never write.

iv) It fits seamlessly on both dad rock compilations and classic rock radio station playlists.

All true, of course, but still: Should I Stay…? isn’t quite the cliched Bryan Adams, rock-lite its critics claim it is. Mick’s thinly-veiled resignation letter is the Stones-go-rockabilly (with a stop-start riff that maybe owes something to Sophistication by Chris Spedding's Sharks) and is enlivened considerably by Strummer’s nonsensical Spanish backing vocals.

And then there’s Rock The Casbah – Topper’s virtuoso moment – a genuine dance-floor filler that took into the US top ten but, 30-odd years later, is as ubiquitous as Come On Eileen or Tainted Love: one of a unique group of 80s anthems that loom so large they MUST be played at every 50th birthday party and second wedding reception.

Meanwhile the connoisseurs wallow in Sean Flynn, an eerie tropical jazz-dub track about Errol Flynn’s son (a celebrated war photographer who went missing in Vietnam) that would’ve fitted perfectly on Sandinista!, and the undisputed highlight, Straight To Hell, a lyrical tour de force – a hymn to the plight of immigrants everywhere – set to an elegiac throb and a rhythm that’s “basically bossa nova,” according to Headon. Tender, compassionate, surreal, playful, there is no other song quite like it.

Combat Rock is all the evidence you need to see why The Clash could never have had the success of U2 or The Police. They were contrary bastards.

Sandinista! (1980)

To a young punk, coming across Sandinista! for the first time is a bit like a 7-year-old facing down a heaped plate of strange food in a restaurant. The sheer volume defeats them before they even start picking their way through it. And then the questions start: “What’re these?” “Chick peas.” “What’s this?” “Okra.” “This?” “Coriander…”

Sandinista! is the same: there’s too much of it, the flavours are weird, and sometimes it’s hard to know what anything is.

A triple album for the price of a single, The Clash’s fourth album is a sprawling, genre-defying, self-indulgent snapshot of a band run wild. Emboldened by the success of London Calling, free of manager Bernie Rhodes, and stoned out of their minds, The Clash delivered an album seemingly tailor-made to piss off CBS and confuse the more conservative elements of their fanbase (“You want punk rock? Try this, sunshine!”).

And that was a major problem in 1980 – when these islands echoed with the sound of fans lifting and dropping the needle across all six sides looking for a Safe European Home, Janie Jones or even a Rudie Can’t Fail and asking themselves one single question: “Seriously: what the fuck are The Clash anymore?”

Even today, it’s understandable. The cliche/true-ism about any double album is that it’d make a great single album – Sandinista! surely stands alone as a triple album you could also edit into a really shit double.

But as two sides of vinyl it would’ve done alright: The Magnificent Seven, Police On My Back, Washington Bullets, The Street Parade, If Music Could Talk, Something About England and One More Time alone could have provided the spine of an album that touched on funk, punk, calypso, rock, reggae and rap and would be talked about in hushed tones today.

Back in 1980 (pre-CD programming or the ability to make your own playlist) Sandinista! was a headache – and a ‘head’ album, music for stoners – an indulgence to rank alongside the worst excesses of prog rock.

Today, it’d probably win the Mercury Prize.

And that’s the thing. Time has changed Sandinista!. I’ve owned it for literally 30 years, and I’m only just getting into it.

The context and expectations have changed. If you don’t come to it hoping for punk rock, you’re less likely to be disappointed. If you do come to it knowing that it’s a patience-testing mess that nevertheless contains some gems, then things get interesting.

The way we consume Sandinista! has changed too. On vinyl it’s annoying and impenetrable. On CD you could program it to skip the worst excesses, or rip it and burn yourself a CD of highlights. On an iPod you could just playlist the best bits. On Spotify or Apple Music you can make the album a playlist and delete the songs you don’t like.

Today you can make your own Sandinista!. Here’s a 48-minute version we prepared earlier on Spotify and Apple Music.

Give Em Enough Rope (1978)

The accepted wisdom on Give Em Enough Rope is that CBS brought in a big-name American producer – a guy from one of those dinosaur rock bands they so despised – in an attempt to turn into Journey or Toto. In fact, producer Sandy Pearlman was no real big name.

Before The Clash, he’d produced his band of outlaw weirdos Blue Öyster Cult, a Mahavishnu Orchestra live album, the first three albums by The Dictators and a Pavlov’s Dog record. And Rope was no big sell-out either – that is, the sound didn’t change dramatically, there were no radio hits – it was just a better-produced (if less inspired) follow-up to their debut.

While that first album was brilliantly parochial in its concerns, Rope widened the scope a little. Musically, its feet were still planted firmly in the London punk scene, but lyrically it’d been reading the International section of the papers – or a Jack Higgins novel, at least.

In his determination to avoid soppy old love songs, Strummer’s lyrics can sometimes come across as slightly immature Boy’s Own adventures – songs about soldiers, drug-dealers, civil war, mercenaries, street gangs and terrorists. These are the songs that later got The Clash labelled ‘macho’ in some quarters and they are undeniably ‘boy-sy’. To call them ‘macho’, though, is to be lazily iconoclastic.

There’s the self-mocking Safe European Home, for example, with its story of Strummer and Jones’s trip to Jamaica (‘I went to the place where every white face is an invitation to robbery/An’ sitting here in my safe European home/I don’t wanna go back there again’) – it isn’t exactly swaggering braggadocio.

And it’s almost unthinkable in this era of bling and social media boasts that a hot young band would write a song like Cheapskates, about what it’s like to be famous but skint (‘Just because we’re in a group/You think we’re stinking rich… An’ you think the cocaine’s flowing/Like a river up our noses’). It’s sensitive, too.

Jones’s bromantic ode to lost friendship, Stay Free, is one of the highlights: musically tender and lyrically heartfelt, even if it is all about getting expelled, shooting pool and doing time. Elsewhere, male violence is castigated, drug use ends in jail time and Julie – the only significant female in the whole narrative – gets the last laugh.

So, yeah, it’s a man’s world but c’mon: boys need songs too. To a generation of young men, it was exactly what they wanted from their rock’n’roll – not bullshit about demons, castles and wizards, not bustles in hedgerows and stairways to heaven, but stuff they could relate to.

The Clash spoke to us in language we could understand (it’s hard to imagine any other major league band getting away with a chorus like ‘All the young punks, laugh your life/‘Cos there ain’t much to cry for/All you young c*nts, live it now/‘Cos there ain’t much to die for’ – The Clash’s audience sang along in full voice) and Pearlman brought a fuller, multi-tracked sound to the band, aided in no small part by the arrival of drummer Topper Headon: his aggression is Tommy Gun’s saving grace and his musicality on tracks like Julie’s Been Working For The Drug Squad gave notice as to where the band could go next.

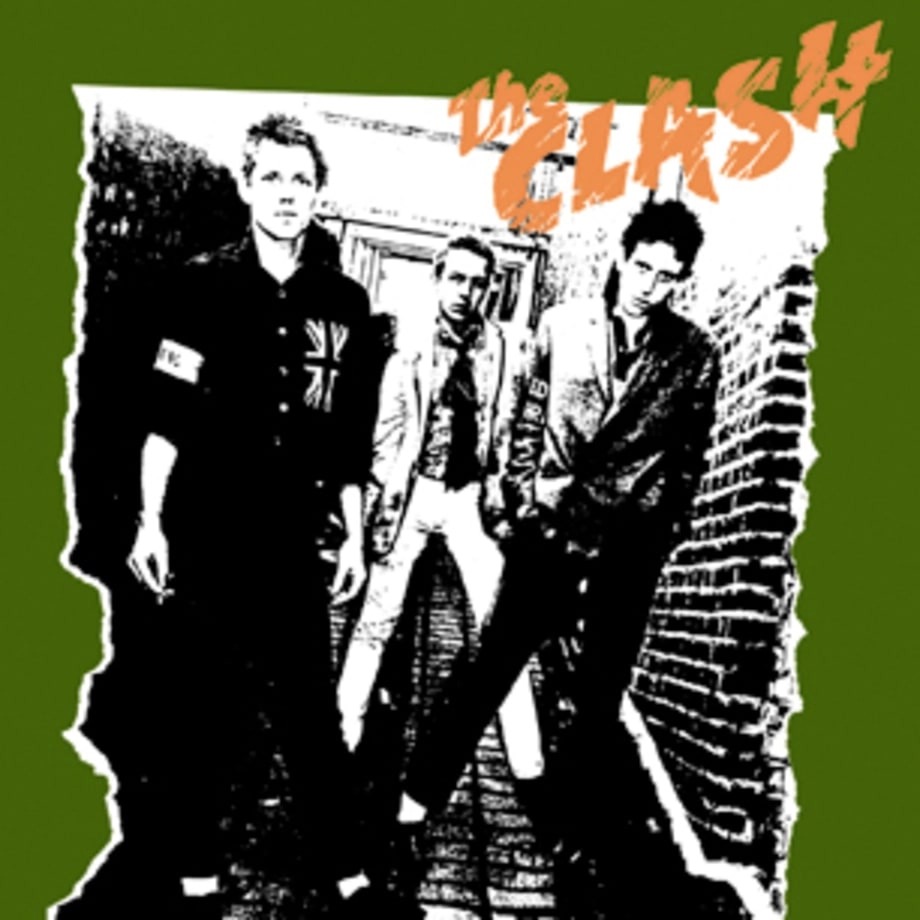

(Note: I have a theory that certain brilliant albums are always destined to be overlooked because they came in such godawful sleeves – packages that only a mother could love. Give Em Enough Rope is Exhibit A in this theory. The only Clash album not to feature the band on the sleeve (until Cut The Crap, if we’re counting that), Rope features a garish sleeve designed by Hugh Brown – though the official album credit goes to CBS in-house designer Gene Greif – of the body of an American cowboy getting eaten by vultures while a Chinese horseman looks on.

Presumably a comment on capitalism from a band still ‘so bored of the USA’, it lacks the iconography of the debut (That picture! That logo! That green!), London Calling (that picture!) or Combat Rock (the military type, the Vietnam-chic). No one’s putting the cover of Rope on a t-shirt or buying the poster for their wall, and that certainly hasn’t helped the album’s standing over the years.)

The Clash (1977)

The holy trinity of punk were so perfectly formed that it’s hard to imagine the scene without any one of them. The Pistols: searing and sneering, nihilistic and iconic (the artwork, the clothes). The Damned: the court jesters. Daft, tough, Tiswas-anarchic, a British Stooges/MC5. And The Clash: the guttersnipes and street punks, the voice you could relate to, and without whom it’s hard to imagine The Jam, Stiff Little Fingers, Sham 69 or Generation X, let alone Green Day, Rancid, or maybe even U2.

The Clash articulated the frustrations of working-class kids in a way that the chin-stroking protest pop of previous generations couldn’t hope to, in a way that was more inclusive than the fury of the Pistols or the Damned’s goth theatre. (And, yeah, genius, we know the irony: Joe Strummer went to a private boarding school and his father was a top diplomat. Hate to break it to you, but David Bowie wasn’t really a spaceman, Tom Waits wasn’t a hobo and Ice-T didn’t really kill cops.)

The Clash was hurriedly written and recorded, and it’s a messy and thrilling snapshot of two creative forces gelling for the first time. From their vocals (Strummer’s yobbish bark balanced by Jones’s boyish sensitivity) to their lyrics (famously, Strummer changed Jones’s track I’m So Bored With You to I’m So Bored With The USA), and even their guitar-playing (Joe’s choppy rhythm guitar versus Mick’s slightly weedy-but-melodic lead), the album is a true Strummer/Jones production.

Both men were classic rock’n’roll dreamers. To find themselves in the right time and right place with the perfect partners must have been a buzz, and amid the anger and the outrage, the album captures that rock’n’roll whoa perfectly.

Mostly The Clash talks about people in boring jobs, with annoying bosses, in a world going to shit. A London burning with boredom, where everyone sits around watching television. Where the TV is full of American cop shows, because killers in America work seven days a week. Where you get hassled in the street by cops and pressured to take a shit job down the Job Centre. Where ‘hate and war’ has replaced ‘peace and love’ and the world is full of cheats and junkies.

Sounds joyless? It’s only half the picture – a bit like describing Trainspotting as a movie about heroin addicts in Edinburgh. The Clash is full of defiance and dark humour and plenty of cheap thrills. Short adrenaline bursts like 48 Hours and Protex Blue (a stupidly laddish ode to the top condom brand of the time: ‘I don’t think it’ll fit my PD drill’) add levity to darker tracks like Deny and Cheat, while Janie Jones, Career Opportunities, London’s Burning and Garageland do all the heavy lifting – full of righteous anger, great one liners and gleeful humour.

Garageland, the witty riposte to Charles Shaar Murray’s earlier line that The Clash were a garage band “who should be left in the garage with the engine running”, isn’t bitter or spiteful but a warm salute to everyone who’s ever been in a dodgy band with ‘five guitar players, one microphone’ and an old bag of a neighbour who calls the police.

Slap-bang in the middle of each side are two tracks about race that would define their career: White Riot and Police And Thieves. Junior Murvin’s Police And Thieves single was released in the UK in July 1976, the perfect soundtrack to that year’s Notting Hill carnival riot and tailor-made for the Roxy, the punk club where Don Letts DJ’d, playing reggae and dub records (there just weren’t enough punk records to play all night and reggae’s outsider status meant it fitted perfectly). The Clash gave the song steel-toe-capped boots and a knuckleduster to create punk-reggae, cementing a relationship between the two genres that continues to this day.

If Police And Thieves embraced multi-racial Britain, both musically and philosophically, White Riot was a little more singular. A two-chord rallying cry – rock music with all the blues stripped out of it (the album version is twice as fast and three times more furious than the laughably rinky-dink 7” version that came out just a month before in March 1977) – White Riot suggests that white people could learn a lot from west London’s black community, that if they too stood up against authority they could take over, instead of taking orders: ‘All the power in the hands/Of the people rich enough to buy it/While we walk the streets/Too chicken to even try it’.

Strummer’s lyric clearly admires the section of the black community that ‘don’t mind throwing a brick’ – the rioters pushed into confrontations by aggressive policing and refusing to take it anymore. Where White Riot becomes problematic is in the fact that its sentiments echo that of many far-right groups.

The National Front had similar views: that Britain was run by bankers (read ‘jews’) and white people should fight back and reclaim their country. Punk rock was a musical white riot – mostly white bands singing music (mostly) stripped of black influence – and a far-right and fuckwitted element of the Oi! movement made much mileage out of this.

If The Clash never really disavowed White Riot, they also never recorded anything like it again.

Police And Thieves showed where The Clash could go – not just deeper into reggae, but also into other musical styles – while White Riot was forever held against them as a reminder of where they came from by a punk audience who wanted their music to get more brutal, not more musical. It was a dichotomy that haunted the band throughout their career.

It split the audience and ultimately split the band too.

London Calling (1979)

As Chris Knowles points out in his brilliant collection of Clash opinions, Clash City Showdown, for a very long time The Clash was regarded as the band’s finest album. American music critic Robert Christgau called their debut “the greatest rock and roll album ever manufactured anywhere” and ranked it as the greatest long-player of the 70s, while UK music weekly Sounds voted it the all-time greatest album in 1985.

London Calling’s stature really began to rise after Rolling Stone voted it the greatest album of the 80s in 1989 (the US version of the album was released in January 1980). A cynic might claim that us poor saps have followed Rolling Stone like sheep in our subsequent reappraisal of the album. It might be fairer to see it as a more balanced reaction to the album after the frostier reception it had on release.

In 1979, two years after their debut, the street-punk baton had been picked up by a ton of bands. Sham 69, Cockney Rejects, GBH and others were intent on having a white riot of their own. Fair enough, you could say. Working-class white kids should be free to have their own music too – music that speaks to them about their concerns and their lives.

But from the outset, The Clash made it clear that they didn’t want that. White Riot was actually urging the white audience to join in, not do their own thing.

London Calling was neither a sell-out or a conscious attempt to crack America. But it can also be seen as a mature musical and political response to a British pop culture that had been transformed by bands like The Specials and Dexy’s Midnight Runners, and a bit of one-upmanship from a band at the height of their powers, encouraged to paint a richer picture by a man with a colourful background in rock’n’roll history.

Producer Guy Stevens had been a pivotal part of the 60s blues explosion, running Sue Records, smoking himself a whiter shade of pale with the likes of Procol Harum and Traffic. Stevens was the Svengali behind Mott The Hoople (guitarist Mick Jones’ favourite band), had recorded early demos with The Clash and was on his uppers in 1979.

Strummer and co dragged him out of the pub and into the studio. Inspired by their deranged father figure, The Clash kicked out the jams in a new, more musical way. By London Calling, drummer Topper Headon could play anything. Paul Simonon no longer needed the notes stuck on the fretboard of his bass. Strummer and Jones were at the peak of their songwriting powers. The sky was the limit.

Train In Vain grooves like classic soul. Guns Of Brixton conjures up genuine London reggae. Rudie Can’t Fail was ska-punk in excelsis. The title track proclaimed a coming apocalypse – and welcomed it (‘London is drowning and I live by the river!’). This was the party at the end of the world. The Right Profile, Revolution Rock, I’m Not Down – the songs on London Calling are a righteous, raucous rave-up.

Recording a blistering version of Vince Taylor’s rockabilly classic Brand New Cadillac, Topper was dismayed at Stevens’ ecstatic reaction at the end.

“We’ll need to do it again,” said the drummer. “We speeded up.”

“All great rock’n’roll speeds up,” said Stevens.

Scott is the Content Director of Music at Future plc, responsible for the editorial strategy of online and print brands like Louder, Classic Rock, Metal Hammer, Prog, Guitarist, Guitar World, Guitar Player, Total Guitar etc. He was Editor in Chief of Classic Rock magazine for 10 years and Editor of Total Guitar for 4 years and has contributed to The Big Issue, Esquire and more. Scott wrote chapters for two of legendary sleeve designer Storm Thorgerson's books (For The Love Of Vinyl, 2009, and Gathering Storm, 2015). He regularly appears on Classic Rock’s podcast, The 20 Million Club, and was the writer/researcher on 2017’s Mick Ronson documentary Beside Bowie.