Although the triple album sprawl of 1980’s Sandinista! from The Clash – the self-styled “only band that matters” – may seem like a more obvious candidate for inspection under the prog lens, its sense of self-importance and lack of musical coherence precludes any such debate.

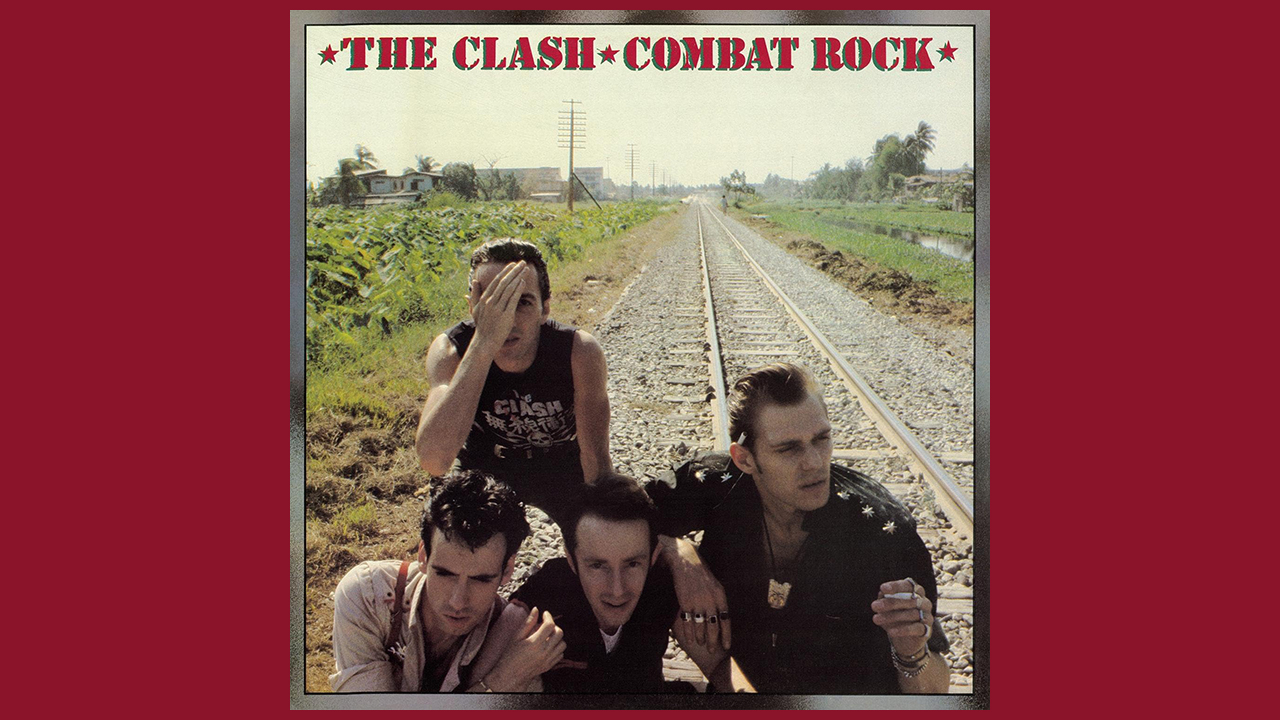

As numerous contemporary prog bands displayed – see Rush’s Signals or Peter Gabriel’s fourth eponymous album, among others – quality wasn’t defined by quantity. Instead, with a focus on the fall-out of the Vietnam war and the decay of American society, The Clash’s fifth album, 1982’s Combat Rock, is not only their last great thematic statement but also the record driven by the most proggy music of their career.

It was originally recorded in New York as a double album under the working title of Rat Patrol From Fort Bragg; but Combat Rock’s future was soon in doubt when newly-reinstated manager Bernie Rhodes questioned the wisdom of releasing yet another multi-vinyl collection.

An additional argument was that the tracks under the auspices of guitarist Mick Jones were getting increasingly longer and – in the case of the 11-minute avant-jazz workout Walk Evil Talk – weirder.

Veteran producer Glyn Johns, who’d previously brought The Who’s Lifehouse project to heel as Who’s Next, was appointed to perform surgery, and he trimmed the material from 76 to 46 minutes to create a flab-free document.

Though they later tried with an ill-advised new line-up, The Clash didn’t need to say any more

Though best known for the single Should I Stay Or Should I Go and its funky predecessor Rock The Casbah, Combat Rock is an album drenched in musical innovation. Witness the floating and eldritch waft of Sean Flynn: it concerns itself with the eponymous photojournalist and son of actor Errol Flynn, who was captured and never released by Cambodian communist guerillas in 1970. It evokes hot jungle nights and potent professional drives via pinging guitars and skittering flutes.

Elsewhere, the minimalist funk-reggae hybrid Ghetto Defender is elevated by a spoken-word contribution from beat poet Allen Ginsberg, as singer and lyricist Joe Strummer laments the flood of heroin into inner city areas as a tool to prevent insurrection.

Straight To Hell is arguably The Clash’s most poignant song – it rails against the injustice of mass unemployment, the babies sired and then abandoned by American soldiers in Vietnam after the war, and the demonisation of immigrants; all propelled by music of haunting drones, insistent percussion and a mood of melancholy menace.

Internal tensions meant The Clash couldn’t last. Drummer Topper Headon was sacked for his heroin addiction before the release of the album, while Jones was fired the following year for supposedly veering away from the original vision of the band.

And though they later tried with an ill-advised new line-up, The Clash didn’t need to say any more. Crucially, they’d pulled away from the orbit of punk into a trajectory that was wholly and unmistakably progressive.