The Cult: "Find me a successful rock singer without problems"

The Cult could have been the biggest band on the planet. Then they split up. Now they're back, but how did they get it all so wrong? Billy Duffy explains…

“I don’t need the money, I’m set for life, financially. The Cult has been good to me.”

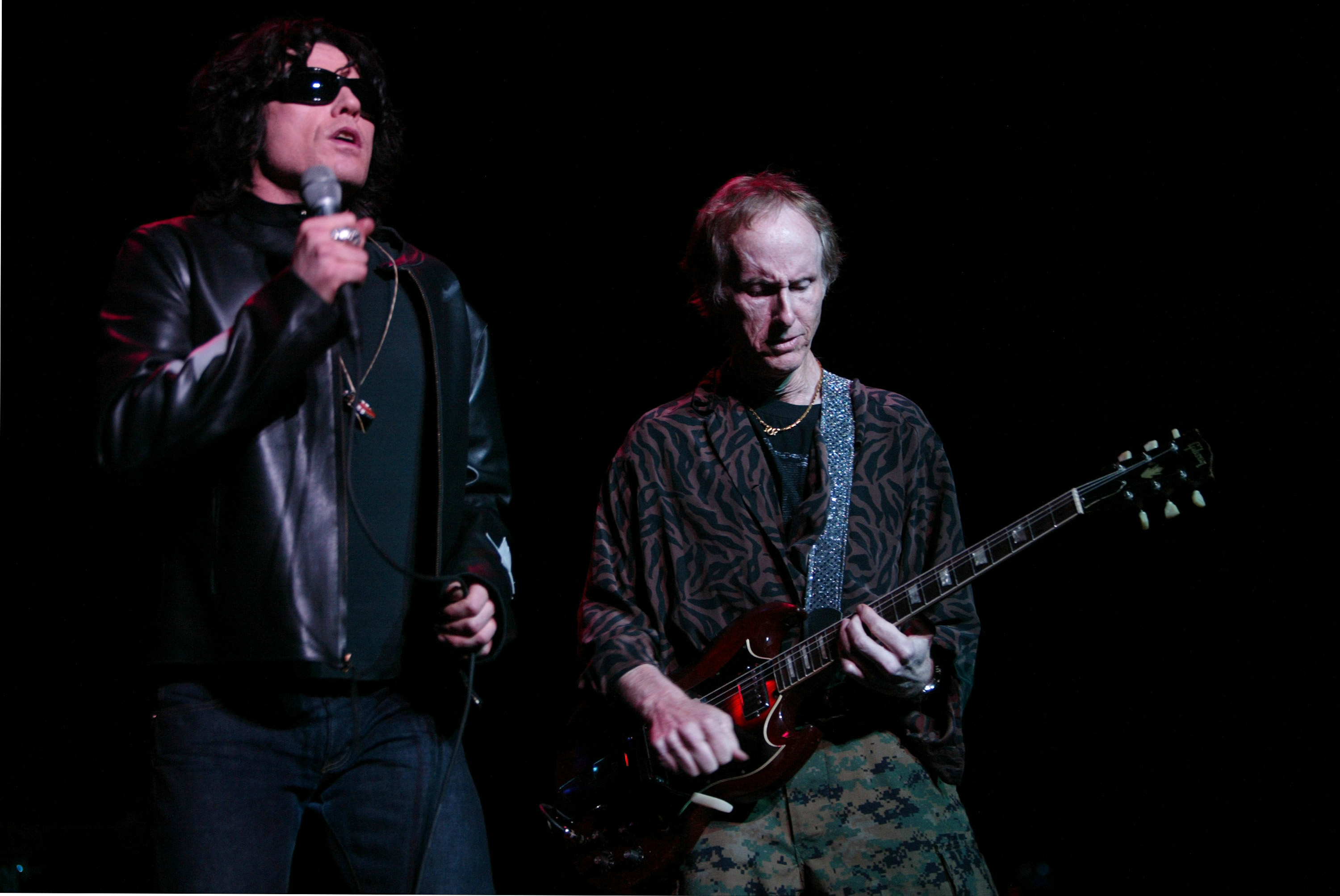

Billy Duffy doesn’t have to do this any more, you know. He’s paid his dues, earned his stripes in the rock’n’roll trenches. As the guitar-slinging Sundance Kid to Ian Astbury’s fire-dancing Butch Cassidy, Duffy has saved rock from itself a dozen times already. He has kept sacred the sonic temple, slain the king of the wolves, seen a billion faces, and clearly rocked them all. His singer moved on. Billy Duffy thought he was finished. But the kids need him. The world’s in chaos, a fireball of war and terror. The downtrodden ache, and the kids ain’t alright. In times like these, you need The Cult.

“It’s really a miserable time to be alive, isn’t it? The kids don’t even have any fight in ’em any more,” says the blond one. “That’s why it’s a good time for The Cult to be around. Our vibe has always had an uplifting effect on people. I couldn’t define why it does, but it does, and I’m just glad that there’s a few bands out there that can lift people up with the music.”

It’s spring of 2007. Born Into This, The Cult’s motorcycle-screaming comeback album, has not been recorded yet. It hasn’t even been thought of yet. The band is still in their feeling-out phase. Billy’s on the line from LA, sounding half-amused, half world-weary. See, he’s already got a new band with his Almighty mate Ricky Warwick called Circus Diablo, and he envisioned a few months of low-key muscle-rock road action, a bunch of wizened old friends hitting the highway for a little adventure, or whatever comes their way. But when you’re Billy Duffy, you never know when you’re going to get that phone call. You can almost imagine that he’s got a bright red telephone like Batman that pulses like a beating heart whenever it’s time to get The Cult back together. It can happen at any minute. Like now. Ian Astbury, high priest of Love Rock, has spent the last few years as a mere rider on the storm, living out his teenage lizard-king fantasies as the Morrison stand-in in a very creaky version of The Doors. Billy didn’t like the whole idea, particularly, but, as he tells Classic Rock, it’s not usually his choice.

“You know, at one point I even suggested that The Doors go out with Ian singing and The Cult as special guests, and we could’ve toured the whole world,” he says. “But of course that didn’t fly. Way too practical. It was Ian’s choice. I didn’t really have any communication with him at the time, whatsoever.”

As to what happened with The Doors, Ian isn’t talking. At least not to Billy or me.

Obviously, a Cult story is a tale of two egos, but Astbury’s input remained elusive the 900 or so times Classic Rock tried to contact him, the raven-maned one having a habit of dismissing interview requests as if they were the pleading of leprous beggars. And so it went with yours cruelly, who went so far as to secure a photographer and a battle plan when The Cult rolled through Boston last year, only to have the sit-down cancelled like a bounced cheque at the last moment. A tragedy, as there were many questions to be answered. Why try on Morrison’s obviously custom-fitted shoes? Why, in recent years, has Ian taken to wearing skirts on stage? Why the live hardcore rap interludes? And seriously, Ian old bean, why the techno record? But Astbury prefers not to answer, or to even address the issues, leaving perpetual cool cat Duffy to simply shrug.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

“You’d have to ask Ian that,” he told me a dozen times during this story, and laughed wearily each time, knowing there was precious little chance of that. The main-man’s media blackout is yet another snag in The Cult’s ascendancy to the top of the rock heap. The last time Astbury deigned to speak with us, it didn’t go well. “As soon as Ian realised that he was talking to a rock magazine – and one that celebrates the past and the present he didn’t really want to know,” recalls the journalist in question. “I”m sure if it had a been a broadsheet or a cutting edge style mag it would have been a different story.”

See, there’s a part of Astbury that makes you think that he doesn’t want to be a rock star. He perceives himself as a poet. A tortured artiste. And, in essence, that’s always been The Cult’s fatal flaw. It’s one that Billy gamely attempts to make up for. When he can. Billy likes to rock, is unafraid to rock, is more than happy to talk to a magazine called Classic Rock. But as to why now is the time to close the Doors and write the next chapter in The Cult’s never-ending story, we can only speculate.

All we know is that Ian’s tenure being the lizard king is over. It may have been the kids and their gnashing of teeth, or it may have been some B52 way up in the sky, but Ian heard the call, and despite a rocky recent history of half-hearted reunions and quick dissolves, he decided that 2007 was the right time for The Cult to get back together. So they did.

“Whether The Cult is together or not, it squarely lies on the shoulders of Ian,” Billy says. “It’s never been about my willingness to do it. He just doesn’t appear to get what he needs from the band, and then decides to do something else. But from what I hear, he wasn’t happy with The Doors either, so when is he happy? It’s up to him to figure all that shit out. As long as he gets up on the stage and does a good performance. That’s what I always do.”

As for the actual resolution, well, there were less tears and blood than you’d think.

“Ian and I sat down in a groovy little diner in Santa Monica and we just talked,” he says.

“It was bit like we had never really gone away. It wasn’t that hard. I think we’re a bit more tolerant of one another now. I think that just comes with age. Now I just really enjoy watching the reaction of the crowd. I know that sounds really clichéd, but I really get off on it. I remember being in the crowd watching the Sex Pistols in Finsbury Park in 1976, and I was really emotionally affected by that. I was really choking up. I occasionally get that vibe when people see The Cult, especially in countries where we’ve never been, like Serbia. There was just this outpouring of emotion, and that’s why I’m doing it now, more than anything else.”

So that’s were it all began again. A groovy diner. But where did it all start?

“Punk rock”, Billy says. “Ian didn’t get to England for a couple years, he was in Canada, I think he got back to England in ’79, but I was there for the whole punk thing. Punk happened while I was leaving high school in the mid 70s. I got to see the Pistols, and it really did change my life, although I found that punk just added to my musical palette rather than changed it. I mean, in my high school band, half the guys were into Crosby Stills Nash & Young and Fleetwood Mac, and the other guys were into Johnny Thunders. That’s how I ended up meeting Morrissey, and that whole thing in Manchester.”

Billy Duffy’s first real foray into the wild world of rock’n’roll was with a hopelessly obscure first-generation teenage punk rock band from Manchester called the Nosebleeds. And, for a very short time, it boasted the singing talents of the most famous mope in the world.

“It was a punk rock band, and I replaced the guitar player,” Billy explains. “He left, and I brought in Morrissey, who was this guy I knew who wanted to be a singer. I met him because he ran the New York Dolls fanclub. I wore out their albums learning to play the guitar. We tried him out, he played two gigs with us. He was really brilliant, but very eccentric. You gotta remember, this was 1978, people were still wearing safety pins. He was way ahead of his time. I remember that we had one song called Peppermint Heaven, and when we played it, he’d throw candy at the audience. His genius was obvious.

“It was good times,” he laughs. “But I wanted to leave Manchester, so I split.”

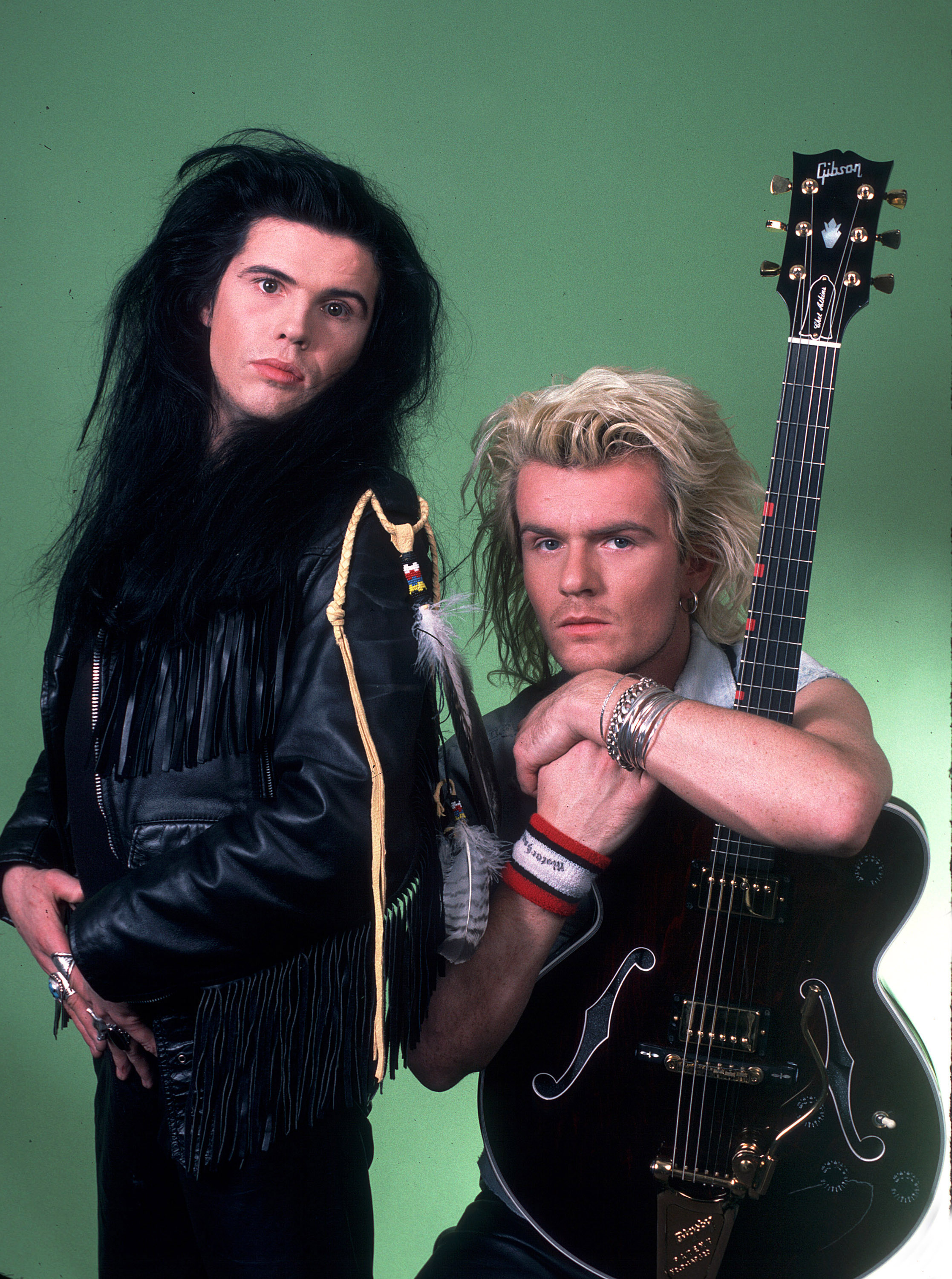

Fast forward to 1983. Billy’s sailed past punk rock and now plays in swirling kaleidoscopes of post-modern psychedelia. He also has a fancier haircut. Meanwhile, Ian Astbury, a tragically handsome young man with wanderlust and a deep affinity for Native American culture, is on his third set of players in a post-punk, pseudo-death rock goth-groove machine originally titled Southern Death Cult, now truncated to Death Cult. They’ve got an album and a rabid fanbase. Astbury paints his face and plays the cosmic Shaman. Duffy joins, great flowers of truth and beauty bloom, and very quickly, “Death” is no longer required. They are, quite simply, The Cult. And they are going to be massive. Almost.

“It was obvious we had something special,” Billy explains. “Ian’s a one-off. He’s a natural born rock frontman. You know, Robert Plant was born to do it, Jim Morrison was born to do it, and I’m not saying he’s as good as those guys, but he is cut from the same mould. Absolutely. You can’t make a guy like that, they just happen. I’ve been around a long time, I’ve seen a lot of wannabe singers, some have the looks, but they can’t sing, some can sing but don’t have the look, some have the whole package but they don’t have the x factor. Ian has it all. He was born to do it.”

In 1985, The Cult release Love, their first major-breakthrough. The album is anchored by the mesmerizing She Sells Sanctuary, a primal, rain-dancing throb of wild love that burns up the radio waves and spreads across England like the most benevolent virus you can imagine. The atmospheric Rain also scores big with UK audiences, and Sanctuary has now snaked across the water, a bona fide monster on US college radio. Already, The Cult is less band and more Big Tent Revival Show. Ian wears leather and feathers, and appears to heal all wounds with songs of ecstasy and devotion. Billy wears ruffles sometimes, but still slings his guitar low, like Johnny Thunders. There’s a pretty infamous Thunders live tape out there where he squeals to a stop and asks his rapturous apostles, “You wanna hear the hippie shit, or the electric shit?”

Significantly, after the runaway success of Love, that’s exactly where The Cult were at. In 1986, The Cult recorded their follow-up album. It sounded just like Love, only less so. It sounded soft, unfocused, too swirly for its own good. Thunders would have scoffed. So the band went to New York, met up with Def Jam’s weird-bearded super-producer Rick Rubin, and proceeded to make what became their most lasting contribution to rock’n’roll, a slavering, stripped-down metal beast that sounded as if it was constructed entirely out of used Harley-Davidson parts. The Cult got their answer. They wanted the electric shit.

“The change in direction was necessary,” Billy says.

“It was really just survival. We recorded the follow-up to the Love album, and probably the songs weren’t well-written enough, and we just didn’t jibe with the producer. We spent a fortune recording it at the best studio in England, the most expensive place, and it just came out crappy, the songs were overwrought, and it just wasn’t right. So we shit-canned it, got Rick Rubin in, and stripped it all down. He’s oft-quoted as saying “I didn’t produce The Cult so much as I reduced them, down to what rock’n’roll really is – guitar, bass, drums, vocals, and a tambourine.’”

The band got wind of Rubin after hearing an early Beastie Boys single, Cookie Puss. They all loved it, and at first sought him out solely to do a remix of their original version of Love Removal Machine, which they had planned to release as the first single on the album.

“Rick met with us in New York,” Billy remembers, “And we sat down and talked about what music we liked, and what the essence of rock’n’roll was, and to Rick it was AC/DC, Led Zep, and early Aerosmith. He said that ‘When you boil it all down, that’s it’. He said, ‘Do you agree?’ And we said, ‘Well, yeah.’ So, he said “Well, you’ve gotta change to get to that place.” In fact, he said – and I’m quoting very loosely – ‘You’ve gotta get rid of all that pussy English shit, and get it back to the rock.’ Billy laughs.

“So, we just decided to redo the whole album. We only went there to mix, so we didn’t have any gear. Everything was rented, right off 42nd street. It was cool, a real good period. You couldn’t write a story like that, man, you couldn’t script it.”

Electric was released in 1987, and it shook that generation of rock’n’rollers to the very core. It was a hit worldwide, but particularly in the United States, where riff-mongering, chest-thumping anthems like Wild Flower, Peace Dog, Li’l Devil and Love Removal Machine perfectly captured that particularly American essence of long-haired, beer-swilling, freedom-loving, hell-raising biker-cool. Hell, they even covered Born To Be Wild for good measure.

“I can see that it had a significant impact on a certain generation in the United States, particularly,” Billy says. “I think in England we had already broke with the Love album and She Sells Sanctuary, but for the US and other parts of the world, it was Electric. It was a portent for things to come, like Guns N’ Roses. People started wearing bandanas on their head again. That whole sound went from the late 1980s until grunge hit in ’90, ’91, just straight ahead rock’n’roll.”

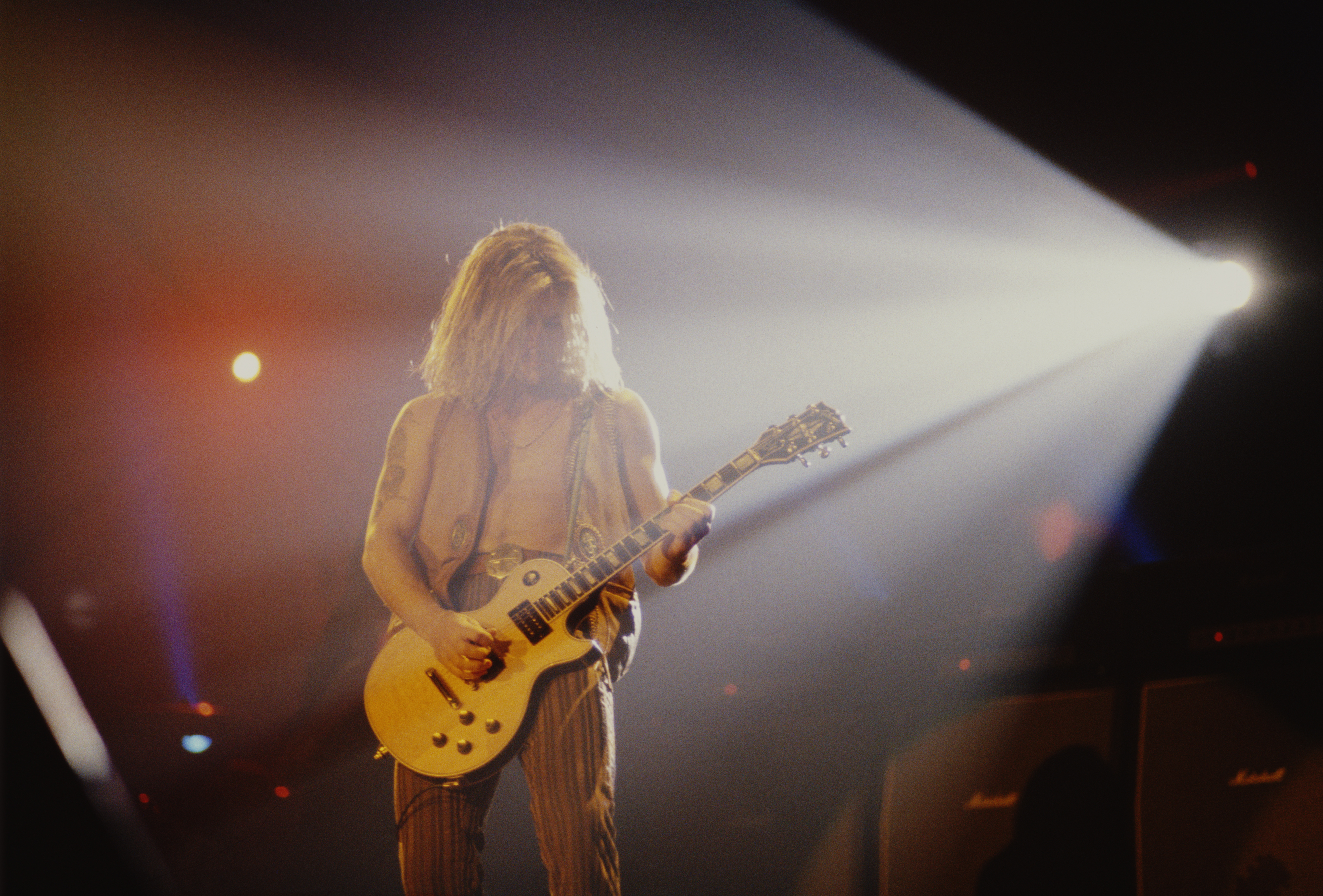

Electric turned The Cult from eccentric hippie-goths to mainstream arena rock juggernauts. They had money and fame and booze and women, and even the Spiritwalker himself succumbed to tired rock’n’roll cliché. Their next album, 1989’s Sonic Temple, was their biggest ever, a great, bloated, fire-belching leviathan that spewed out hit after hit – Fire Woman, Sun King, Sweet Soul Sister, and even a lighter-waving power ballad, Edie (Ciao Baby). It may, in fact, be the most out-and-out rock album ever created. And it nearly killed its creators.

“If you asked Ian and he was really being honest,” Billy says, “I think he’d tell you that the he didn’t do the band the greatest service during the Sonic Temple era, when we were potentially at our biggest. I think he was very uncomfortable with the success. I don’t think he liked the album, and I don’t think he liked what he was doing. As a subsequence, he put on a lot of weight, and his vocal performance became pretty poor. I guess that was just his way of displaying his displeasure, looking back at it. Regardless of the material success of the band, it wasn’t what he wanted to be doing, yet he went through it. It was kind of like shooting himself in the foot a bit. But we all have our demons,” he sighs. “Find me a successful rock singer without problems.”

Despite their wealth and fame, the great saviours of rock began to lose their faith. Duffy and Astbury’s relationship soured over time, and by 1991’s Ceremony album, they rarely even recorded in the studio together. Sales slipped, but the crowds still surged. 1994’s self-titled album, although a creative triumph, failed to land with the fist-pumping scruffs that wanted only to worship in the Sonic Temple. By 1995, Astbury had had enough. And the next dozen years became a rollercoaster of break-ups and reunions.

“We broke up in 1995”, Billy says. “That was a real break-up. We were in South America, and Ian just split. I think the problem was that neither of us were ever very comfortable with success. We’re just not cut out for being pop stars. It’s not something that either of us ever wanted. It’s like Ian Astbury once told Lars Ulrich, ‘Don’t confuse bigness with greatness.’”

Both men went their separate ways. Ian released a techno-inspired solo album and formed the short lived Holy Barbarians. Duffy played in a band called Coloursound with Mike Peters from the Alarm.

“Me and Ian barely saw each other in that period”, Billy says. “From 1995 to 1999, I literally saw him probably once or twice a year, casually, somewhere. That was the reality of what it was like. We were on two different paths.”

In 1999, the band got back together and hit the road. Emboldened by the gathered faithful, The Cult went back in the studio and recorded 2001’s Beyond Good And Evil, an album full of epic, moody hard rock anthems. It hit the ground running, but those were doomed days, and by the end of that embattled year, The Cult called it quits again.

“In 2002, it just kinda fizzled out,” Billy says. “We did the album, and then everything went to Hell.”

“Only we could release an album four months before 9⁄11, and be halfway through promoting it when the whole world changed. Then the downloading of music was happening, and we were kind of caught up in that, as bystanders in this big shift. We did a few shows in 2002, but literally, we did about six gigs, and that was it for us.”

And that’s where the story ended. Until now

“We have staying power, that’s for sure,” laughs Billy. “I don’t know how that happened, but we evidently have some endurance.”

You know the rest of the story. The initial tours were a smashing success, with throngs of worshippers raising horns of supplication in the Electric Church. Buoyed by the devotion of the fans and alarmed by the darkness of the days, the band wrote and recorded the return-to-form Born Into This, which made many Best Of 2007 lists and re-established The Cult’s rightful status as one of the greatest hard rock bands to ever wear furry hats and sing songs about devil women.

Asked about the band’s enduring appeal, Billy has a simple explanation: “It’s always been cool to like The Cult,” he says. “The Cult has never been uncool, ever.”

Amen.

This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #116.

For more on The Cult’s Billy Duffy and the albums that drove him to pick up the guitar, then click on the link below.

Came from the sky like a 747. Classic Rock’s least-reputable byline-grabber since 2003. Several decades deep into the music industry. Got fired from an early incarnation of Anal C**t after one show. 30 years later, got fired from the New York Times after one week. Likes rock and hates everything else. Still believes in Zodiac Mindwarp and the Love Reaction, against all better judgment.