Back in 2001, metal was in rude commercial health. Linkin Park and Limp Bizkit had taken nu metal out of dingy clubs and into the world’s stadiums, and Slipknot stunned the world when Iowa reached the summit of the UK album charts. But not everyone was impressed by our shift towards this new breed of rock star. Deep underground, in Boston, Massachusetts, a band were about to unleash an album that couldn’t have been more complex, more raw, more challenging and more at odds with alternative culture’s dalliance with the mainstream. As anyone that heard it at the time knew, Converge had changed the game and Jane Doe was their masterpiece.

“2001 was a wild time,” says vocalist Jacob Bannon today, when asked to reflect on what magic created such a record. “Both musically and creatively we all had a lot going on in our lives. A lot of it was negative, but a lot of it was positive and helped bring us together as a band.”

At the start of the millennium, Converge were a collective made up of various members of the wildly fertile Boston hardcore scene, and three albums of absurdly heavy, metallic hardcore had put them on the underground’s radar. Although it wasn’t a place they felt comfortable with.

“We were never, and we still aren’t, cool,” Jacob says. “We never appealed to that which was going on in the metal or the hardcore world. I remember this quote from Steve Reddy at Equal Vision, who signed us in the mid-90s. He saw us play in front of about 1,000 people with Coalesce and Deadguy – those were our peers at that time – and he said that he didn’t understand it. But he saw the energy and felt that he needed to be part of it in some way. Even then the hardcore kids thought we were too metal. I think some of our outward angst and antagonism as a band came from that attitude. We just wanted to play as hard as we could and leave as much emotion out there as we could.”

This attitude was about to be harnessed in the most incredible way, but it took the introduction of bassist Nate Newton and drummer Ben Koller to join Jacob and his fellow founding member, guitarist Kurt Ballou, into the ranks of Converge before they truly had the tools to make the album inside their heads. And even that came at a price.

“At that time, Aaron [Dalbec, guitar] was still in the band,” nods Jacob. “Aaron is still a friend of ours but we were gelling a bit more as a group without him. We were writing more together, we rehearsed more together, and when we went in to record it really felt more like a quartet kind of thing. It weighed on us, it was a stress, there was tension there. The dynamic on one hand was great – the four of us were really evolving and growing as a unit, and we were really happy about that – but there was another thing where we were not happy that our second guitarist just wasn’t as present as we wanted him to be. I think addressing that and having to go through that brought the four of us together. That was a really important part of that record.”

As the band began to write, Jacob began to piece together what would become one of Jane Doe’s most essential characteristics: the unflinchingly personal lyrics, giving you a brutally honest perspective of a relationship breakdown.

“One of the things I liked in bands that connected with me was that personal connection,” Jacob says. “When I was first starting to write songs as a teenager, I didn’t feel like I had a fully formed idea of the world that I could put in a bottle and write lyrics about. So when I would write, I would write about my life and the things I was going through – it was a way to help me through those things. When I was writing the Jane… lyrics, I had some stuff going on that wasn’t positive, and I was just trying to find myself. To own that emotion, that rough place I was in, and make sense of it. It’s funny: lyrically it’s a pretty put-together album, but at the time I felt like I was just going off on tangents. I think going through that and reacting the way I did back then, that was how I found my creative process.”

As Converge went in to record Jane Doe, Jacob revelled in this process of self-discovery, submerging himself in the bleak feelings that were flowing from his mind.

“I was certainly embracing the emotional chaos,” he tells us. “I recall recording some vocals in the dark at Fort Apache studio on the stage where they did these live sessions. It was an odd feeling to be in this room in pitch black, alone. It was kind of apt for the material.”

Jane Doe was released on September 4, 2001, and immediately sent shockwaves through the punk, hardcore and metal underground. From the opening chaotic 79-second blast of Concubine to the closing title-track’s nightmarish 11+ minutes, the album beautifully melds pure punk rock aggression, musical dexterity and heartbreaking emotional honesty to breathtaking effect. It was so perfect that, to the shock and awe of everyone involved, even the metal media had to take notice.

“I used to buy music magazines all the time, and for the longest time that world just wouldn’t acknowledge our scene,” Jacob remembers. “It was either death metal bands, like the early Relapse bands, or it was Cradle Of Filth everywhere. People just didn’t talk about punk or hardcore. So it was strange to see, but also at that point I realised really quickly I didn’t want to read about my band from other people. I don’t care to look at press. Creating music is a really personal thing and people can discuss and dissect it, but they’ll never get close to what it really means.”

Such was the reach of Jane Doe that, inevitably, bands saw this new blueprint and did all they could to ape it. In the US, Converge opened up doors for their peers and contemporaries in bands such as Poison The Well, Every Time I Die and Cave In to sign deals, and inspired everyone from Misery Signals to Norma Jean to make hardcore heavier and more technical, emotional and thoughtful. In Britain, the likes of Beecher, Johnny Truant and Eden Maine became scene darlings on the back of Jane Doe’s sonic blueprint.

“Sure, we saw that,” Jacob smiles. “We still do. You can look at that in so many ways, you can get angry or spiteful. But if people are emulating you, or trying to emulate what they think you are, then that’s OK, you’re affecting something. It may not be your goal, but it is what it is. But we’re one of those rare bands that started at an early age and have evolved in front of people. So for the bands that are inspired by us, hopefully that will lead them to some place cool.”

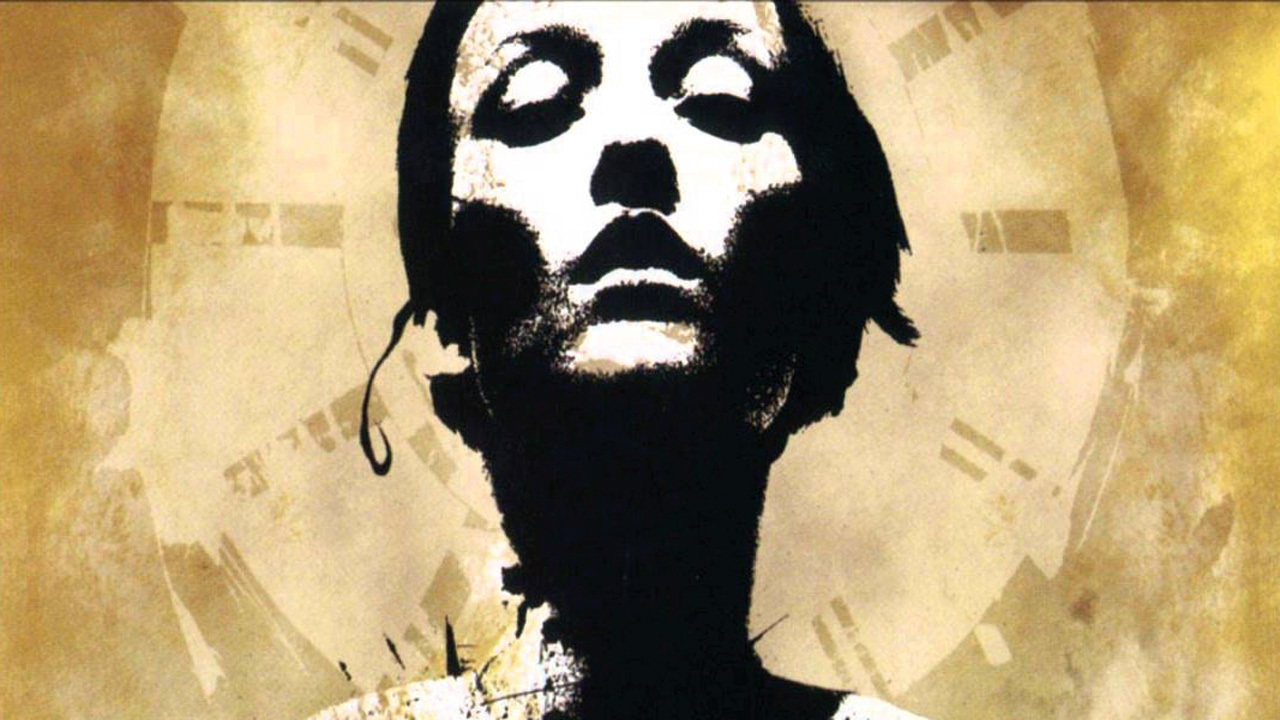

Another striking feature of Jane Doe is the artwork, which was created by Jacob himself. The monochrome, high-cheekboned face of Jane stares fixedly downwards, and is now seen adorning the skin of fans worldwide. Back then it was striking, but today it’s utterly, inarguably iconic. Jacob initially hired his friend and previous Converge sleeve designer Derek Hess, fearing he was too emotionally immersed in the songs to do it himself, but soon realised he could channel those feelings to make something great.

“I was emotionally wrapped up in the record, so I didn’t think I could do it. I just wanted to palm it off to someone else, and I thought Derek’s work would fit the narrative. But it wasn’t connecting,” Jacob remembers. “I was experimenting with a lot of cut-and-paste collage stuff, punk rock crossed with fine art. So I thought I’d do something quick from spray cans and ink. It just took on a life of its own. I knew I’d created something I was really happy with; I felt it really captured the chaos of the music, but gave some order to the piece. But I never knew how impactful it would be to people.”

Although not everyone was happy with the result.

“The label were pissed,” laughs Jacob. “They hated it. It didn’t have the Converge logo on and I got a lot of pushback. I think that was probably the first time I really felt like Equal Vision as a label were not a label that understood the creature that we were. We were just starting to become excited by what we could do as a band.”

As time has progressed, Converge have become one of the most beloved, singular cult bands on the planet. But there is still a place in people’s hearts for the album that set fire to the punk rock rule book, as evidenced by the outpouring of love when Converge were confirmed to play the album in its entirety at last year’s Roadburn festival. The set was captured on tape and has been released as Jane Live.

“When Walter [Hoeijmakers, promoter] from Roadburn approached us, we really wanted to make it work, because we really respect his festival and his approach,” Jacob says. “He tries to get bands to do things that they don’t usually do. He wants it to be a really unique event. We frowned on the idea for a while, but we thought that if we were ever going to play the album like that, then it would have to be in a place like Roadburn. That way we can rehearse and play the songs how we play them now, because we don’t play them all these days. But we won’t be doing it again; we won’t be doing a tour. As much as I’m proud of the album, we always want to look forward.”

Converge continue to push boundaries, but Jacob also recognises the journey he and his band have been on. If it wasn’t for all their history, and the turmoil of Jane Doe, they might not be who they are today. When he thinks of the album now, he’s still able to relate to the dissatisfied young man who was going through such rapid change.

“It’s obviously not the same,” he begins, “but it is similar, because I’m the same man. I’m not a different person. I don’t look at life in stages and blocks – it’s all one life that I’ve lived. I’m as proud of that record today as I was then.”

Jane Live is out now via Converge Cult.

Every Converge Album Ranked From Worst To Best

Converge live review – London, Electric

The 10 Best Converge songs, according to Touché Amoré frontman Jeremy Bolm