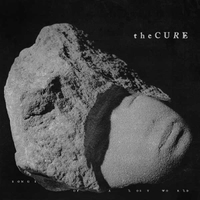

For Robert Smith, black has always been the new black. In a career spanning almost 50 years, the haystack-haired singer has steered his band The Cure through the gloomy aftermath of punk, patented much of the goth aesthetic, dabbled in psychedelia, and recorded a huge canon of all-time classic alt-pop anthems. With the release of their first album in 16 years, Songs Of A Lost World, The Cure have reclaimed their throne as alt-rock elder statesmen, a seminal influence on multiple younger generations and musical subcultures, from shoegaze to grunge, emo to nu-metal and beyond.

The shorthand caricature of The Cure’s sound would be Smith’s whimpering adolescent angst set to a spangled churn of minor-key guitars, yet these perennial cult favourites have actually amassed a remarkably eclectic body of work over the decades. Their opening suite of youthful albums was rooted in the monochrome angularity of post-punk, but during the 1980s they also embraced roaringly romantic pop, jazzy textures and stadium-sized goth-rock dynamics. An enduring fondness for psychedelia also runs through Smith's musical hinterland, as manifested in Hendrix and Doors covers, a fondness for trippy guitar effects, and a flair for phantasmagorical imagery that taps a rich tradition of English literary surrealism ranging from Lewis Carroll to Edward Lear to Mervyn Peake.

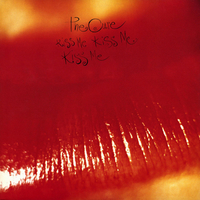

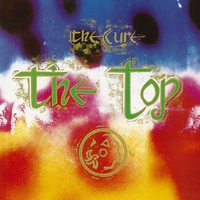

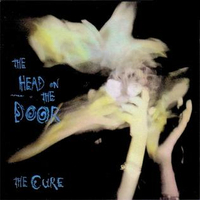

Alongside Def Leppard and Depeche Mode, The Cure were one of the few British bands to truly conquer America in the 1980s and 1990s. The panda-eyed, lipstick-smudged Edward Scissorhands of rock greeted each new creative rebirth with wild mood swings between bleak despair symphonies and fizzy, giddy, super-catchy jangle-pop love songs. On more accessible albums like The Top and The Head On The Door, the band stopped being sullen outsiders and blossomed into a universal cult that everyone could join. In the process, they became part of the global pop fabric, inspiring cover versions by everyone from Smashing Pumpkins to Adele, Dinosaur Jr. to Tricky, Mark Lanegan to Phoebe Bridgers.

As The Cure’s sole remaining founder, Smith has had boozy fights and fall-outs with numerous former members, reshaping the line-up multiple times. Over the last decade, the band has absorbed former David Bowie guitarist Reeves Gabrels, whose avant-metal pyrotechnics helped re-energise their sonic palette on the huge-sounding Songs Of A Lost World. Once they were arty punk-pop outsiders. Nowadays, their multi-guitar-chugging assault can feel more akin to seeing Neil Young in full Crazy Horse mode, or even a kind of gothic Led Zeppelin.

Almost half a century on, Robert Smith remains one of British rock’s true originals