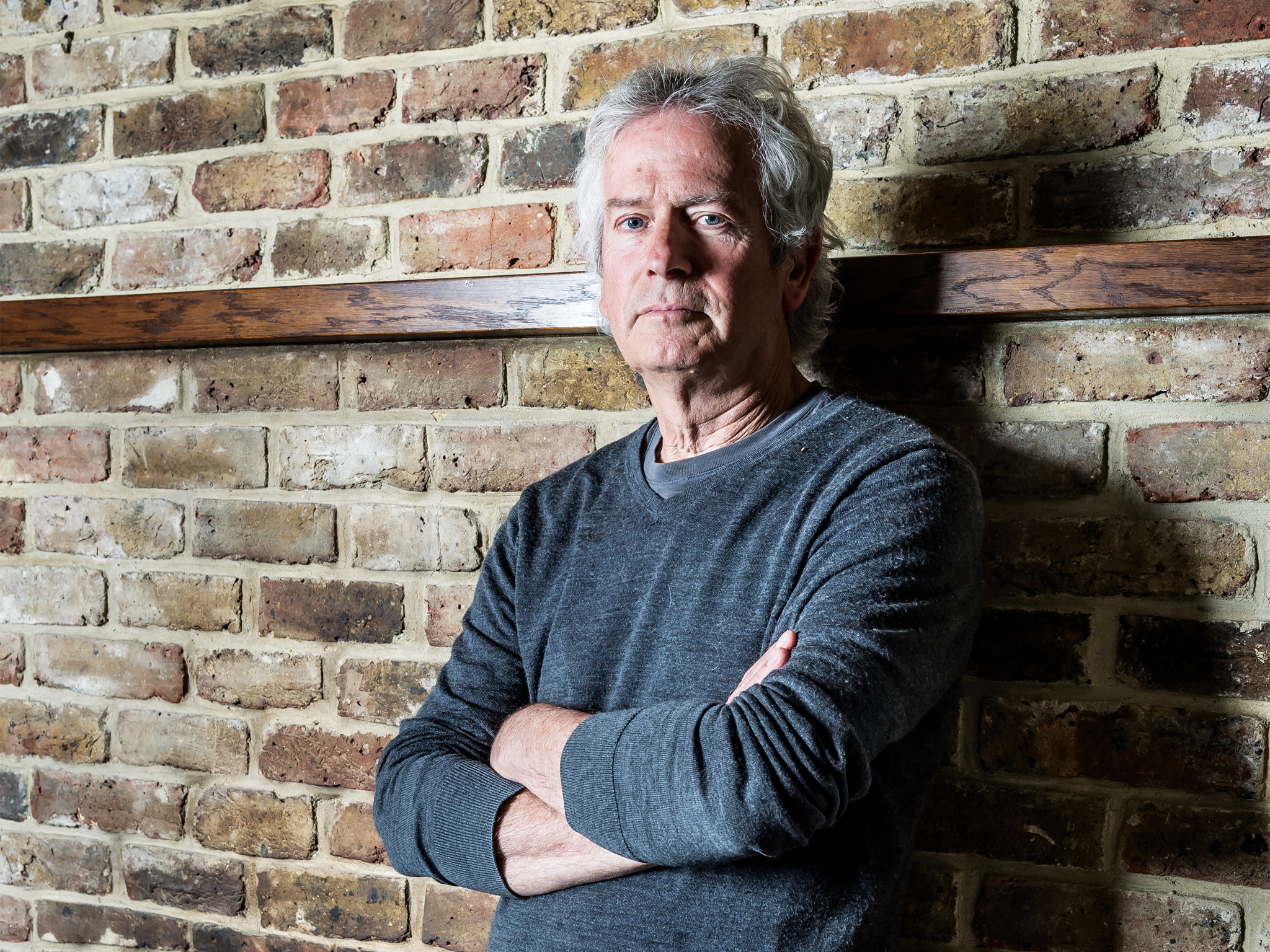

In person, Tony Banks is a mixture of wry humour, deep thought and witty self-deprecation, and has a quicksilver quality so difficult to capture in print. His work is something he takes very seriously and his painstaking quality control shows across A Chord Too Far, his new four‑CD retrospective on Esoteric. When you listen to the body of work, it’s unmistakably Banks, and underlines his role as the principal architect of the Genesis sound.

Banks is characteristically honest about his catalogue. “I really enjoyed myself making these records – it was just putting them out that wasn’t so much fun. If I hadn’t had Genesis, I might have tried a bit harder, but I was always content to do what I wanted. What was the point of compromise?”

This is something that resounds clearly in Banks’ music. Although some pieces may contain the obligatory machinery of the day, there are no rave extravaganzas or Eurovision pop. In fact, there’s little compromise or deviation from Banks’ core business: well-written songs based on incredible chords.

“Songs can be great for getting across simple emotion,” he continues. “You can say something banal in a song and it can work fantastically. I’ve always tried to avoid using chord sequences – as a writer I find that dull. I’ve done it occasionally – say on Land Of Confusion. Sometimes the people who do best are those that do one thing and flog it to death, but I like short, I like long, a bit of complex.

I don’t have a great voice, but then a lot of people don’t have great voices. There’s something about a person singing their own songs that really works.

“I’ve always been uncompromising in a way, and that’s always been part of the problem why the records haven’t appealed very widely. I’ve never been in it for that reason.”

When Banks released A Curious Feeling in 1979, it was the first of the new era of Genesis solo albums. Steve Hackett had released Voyage Of The Acolyte in 1975, and Peter Gabriel had released two albums by that juncture, but Banks was the first of the continuing group to go solo. Had there been any reticence on his part to go it alone?

“Oh no,” he states emphatically. “I wasn’t sure we were going to make another Genesis album when Peter left. I wrote a lot of stuff, like Mad Man Moon, A Trick Of The Tail and large parts of the other songs on that album too. I was very glad not to do the solo album at that point because I wasn’t ready for it. Once we realised it was going to work without Peter, I was very happy. Putting it off until later suited me.”

A Curious Feeling was recorded at Abba’s Polar Studio in Stockholm during the sabbatical Genesis had after the …And Then There Were Three… album. “I was really ready for it as I had so much material,” Banks says.

Initially, he was going to record an album based on Daniel Keyes’ novel, Flowers For Algernon. While writing, Banks became aware of a 1978 musical, Charlie And Algernon, based on the story. Banks rewrote, but kept many of his existing themes.

A Curious Feeling was made with Genesis live drummer Chester Thompson and ex-String Driven Thing vocalist Kim Beacon, with Banks playing the rest. “I played everything for two reasons,” he laughs. “One was that I knew I wasn’t going to sing, so I felt I had to do something, and the other was my slight inability to delegate! It’s one of my favourite 45 minutes that I’ve done and I thought Genesis fans would like it as it was following on from things like One For The Vine and Afterglow.”

And like it they did. It was released in October 1979 and reached No.21 in the UK chart, but it didn’t linger on the listings. “It was a little bit too late really,” Banks says. “We were well into the punk era by then and it had no press backing and dismissive reviews. I hadn’t realised how important singles were by that stage, and I didn’t really have one.”

A lot of the album’s success can be attributed to Kim Beacon’s vocals. “I’d always had a slight problem with the album being credited to ‘Tony Banks’ and yet I wasn’t singing,” Banks says. “I got a letter from Pete Townshend at the time, which was very complimentary about the album. He said he loved my voice. I really didn’t know what to say to that so I never got back in touch with him. I met him many years later and he said, ‘Why the fuck didn’t you reply?’ And I said, ‘Because you said I had a great voice and I wasn’t the singer.’”

There wasn’t a great deal of time to ruminate on the fortune of A Curious Feeling as it was quickly back to business with Genesis. 1980’s Duke, one of Banks’ favourite Genesis albums, can be seen as closing the group’s prog era and ushering in their pop years. After the success of Duke, then Abacab and the resulting tour, Banks didn’t get the opportunity to go it alone again until 1983, when he did so twice, in two very contrasting styles.

I really enjoyed myself making these records – it was just putting them out that wasn’t so much fun.

He made The Fugitive, arguably his most straight-ahead rock/pop album, recorded at The Farm with Stephen Short as his co-producer. While he was making that, he received a call from Michael Winner to see if he was interested in scoring his remake of the 1945 Margaret Lockwood bodice-ripper The Wicked Lady. Banks had already written, with Mike Rutherford, the score for 1978 film The Shout, and the experience hadn’t been wholly fulfilling, but he was intrigued and went to meet Winner.

“I thought it would be fun,” Banks says. “I would watch it, play the piano and Christopher Palmer would orchestrate. I wrote the main theme and about five other themes.”

Banks got on well with the larger-than-life Winner. “Michael was very enthusiastic and really liked my stuff. He knew what he was doing. He had a certain amount of pomposity, but he would put it on. He was very self‑deprecating.”

The film, sadly, was an enormous misfire. Its Oscar-winning lead, Faye Dunaway, picked up a Razzie for her efforts. “It wasn’t very good, although it had a great cast. That’s one of the downsides of film music. I spent all that time on it, but if it’s not very good, no one hears it.”

The Fugitive, released in June 1983, was a very different work from The Wicked Lady. The album was full of focused pop. Banks decided to sing throughout the record, the first and only time he did so.

“I don’t have a great voice, but then a lot of people don’t have great voices. There’s something about a person singing their own songs that really works, and that’s why singer-songwriters prove so popular. I mean, Dylan hasn’t got a voice at all, but one likes to hear him singing. Some tracks worked better than others…”

Indeed, it’s a really intriguing listen, with guitar from Genesis live player Daryl Stuermer throughout. It stands up well against Rutherford’s one-off all-singing album Acting Very Strange from the previous year.

“It taught me a lot about songwriting,” Banks says. “It made me think about what I write for singers. Phil was very good about being able to sing what was put in front of him. Peter sometimes had more trouble with it and would occasionally get bolshy about things. Singing yourself teaches you why. The lyrics needed be straighter. You can’t sing about nymphs and faeries forever. The songs became a lot more about relationships.”

Banks’ next solo work was released in March 1986. Soundtracks tidied up the pieces he had written for two films that came his way after The Wicked Lady. One was a low-budget Anglo-Australian film eventually titled Starship; the other was the Kevin Bacon post-Footloose vehicle Quicksilver. “Kevin Bacon has made a lot of excellent films. Quicksilver is not one of them,” Banks notes wryly.

Director Peter Hyams asked Banks to write the music for 2010, the sequel to 2001: A Space Odyssey. However, according to Banks, Hyams lost confidence in him. Leaving the project, Banks took the Redwing Suite he had written for 2010 for the film Starship. This seldom-seen film is not highly rated, yet Lion Of Symmetry, the track Banks recorded with Toyah (who appeared briefly in the film as a singing hologram, of course), is one of the highlights of his solo work.

Quicksilver was an unsatisfying experience but offered Rebirth, the beautiful instrumental that Banks selected to open A Chord Too Far and Shortcut To Somewhere, a collaboration with Fish. Although it ultimately wasn’t used in the film, it’s an endearing slice of mid-80s hokum, overseen by early Spandau Ballet producer Richard James Burgess. “There were too many words,” Banks states. “I was trying to thin them out, but Fish had to have all his lines! That time, I would have compromised. I asked Richard to chop it around and make the hook happen more, but it was recorded as I’d written it.”

Soundtracks was a neat tying of these filmic loose ends. Not that anyone outside the hardcore noticed, because the next Genesis album, Invisible Touch, soon made them global superstars. The whirlwind of touring and having a US No.1 single meant that for a while there was simply little time to maintain a solo career. When thoughts turned back to individual work, Phil Collins had by now become a solo global megastar and Mike Rutherford, with his Mike + The Mechanics, was having huge UK and US hits.

Surely the time was right for Banks to have a piece of the solo action. “Phil got increasingly popular, and then Mike did something very clever with Mike + The Mechanics. Phil was very much the man, and people were getting more star and celebrity conscious.”

Banks has never been one to court celebrity – not that he doesn’t get out and about. “It’s fun sometimes to mix with stars and go to fancy things, but I don’t crave it at all – I’m much happier staying at home and doing my thing.” He pauses. “When I do go to things, no one takes pictures, or if they do, they go, ‘Who’s he?’”

We put Seven: A Suite For Orchestra out and for the first time in my life, we got good reviews – it was a very exciting for me.

In 1989, Banks tried a new approach. Inspired by Rutherford’s repositioning of himself with a group, Banks formed Bankstatement, where he was joined by two vocalists, Manchester-based Alistair Gordon and Australian Jayney Klimek. The resulting self-titled release was a confident album of late-80s pop. Virgin MD Jeremy Lascelles suggested Steve Hillage produce. “I’d never met Steve,” Tony says. “I thought, naturally, that he would play lots of guitar. He was going through a phase of not playing. It was a struggle to get him to play anything. There was a song called Raincloud, where he was just standing there with his guitar, waiting for inspiration, and then eventually a solitary ‘doinnnng’ came out! Because I had him, I didn’t get Daryl involved, and I think it lacks a bit from that point of view.”

Banks heard Gordon through audition tapes, and Hillage recommended Klimek. The two voices offered a great contrast. Aside from some promotional appearances, the band were hardly seen and as a result, the album didn’t take off. Did Banks ever consider playing it live?

“I couldn’t bear to have gone out there with nothing,” he says. “I didn’t want to do all that, start again from the bottom, as I don’t feel I have enough to give. Live is my least favourite part of the business. I’m very pleased with Bankstatement. It didn’t set the world on fire. You have to keep trying and I was lucky that I could, because being in Genesis gave me that ability to put these records out.”

Banks went back to using his own name for his next release, Still. Released in April 1991, it’s arguably his best, and although using a variety of vocalists, it retains a tremendous consistency. “Still is my most rounded album, and very satisfying. It was the first time I had worked with [producer] Nick Davis, a very enthusiastic supporter. When it came out, lots of people thought this was the one that was going to do it. “

Although Clark Datchler from Johnny Hates Jazz had originally been involved, Banks used Fish and Jayney Klimek again, Andy Taylor (not the Duran one) and former pop sensation Nik Kershaw who, like many of his generation, was a prog rocker at heart.

“Nik was pretty unwilling to do too much promotion,” Banks sighs. “He wanted to back out of the public eye at that point, and he’d just had a massive hit with that Chesney Hawkes thing so he wasn’t needing it in quite the way that I was. I thought Still was as good as I would do. I thought that was it.”

The global success of We Can’t Dance saw Banks busy again, and by now, thoughts of going solo were being put from his mind. However, in 1995, there he was, back again with a new album and a new outfit, Strictly Inc. “I’m not quite sure why I did Strictly Inc,” he says. “I had time on my hands and Genesis were on a rest.”

Banks was now making music for himself, not worrying about being a commercial or critical success. As a result, it contains some of the best – and most overlooked – work of his career.

Nick Davis had been working with Wang Chung vocalist Jack Hues and thought he would be a perfect voice to complement Banks’ music. The highlight of the album, and arguably of A Chord Too Far, is the 17-minute-plus An Island In The Darkness, a multi-sectioned opus that encapsulates all that’s great in Banks’ writing.

“I really wanted to do a longer piece but I didn’t want it to be a parody of what I’d done in the past. I had a theme, a bit like I’d done in Firth Of Fifth, played quiet and then later played loud. That was the starting point. Daryl came in to do the big solo. I was very pleased.”

Sadly, the album barely made a ripple, and only now thanks to its appearance on A Chord Too Far can we appreciate Banks’ craftsmanship.

There has been a most satisfying coda to Banks’ solo career. In 2004, after one last roll of the dice with Calling All Stations and then tidying up the Genesis archive, Banks decided to cross over into the calm, expansive waters of classical music.

“After promising myself I was never doing another solo album again, Genesis finished. I’d always had the theme for The Wicked Lady in the back of my mind, which had come alive with an orchestra, so I thought I’d give it a go again. I had a few pieces around – I wrote Black Down on string synthesiser in one pass.”

After an abortive initial attempt to record, Nick Davis came on board, as well as Mike Dixon, who’d been the musical director on the stage show of We Will Rock You. Having his foot in both classical and rock camps meant Banks’ ideas could easily be translated to an orchestra. In this case, the orchestra was none other than the London Philharmonic.

Free from his Virgin contact, Banks released Seven: A Suite For Orchestra in March 2004 on Naxos, the classical specialist. “We put it out and for the first time in my life, we got good reviews – it was very exciting for me.”

Playing the Genesis reunion shows in 2007, Banks kept being asked what he was going to do next, and he thought he needed to say something.

“I talked myself into doing another. I got a new lease of life. I got in touch with saxophonist Martin Robinson, violinist Charlie Siem and orchestrator Paul Englishby and SIX Pieces For Orchestra was created. To get these guys to keep every chord I’d written was a struggle sometimes, but it was a very interesting experience.”

Banks tells us that he thoroughly enjoys his classical work. “There is a lot for old proggers to enjoy as it does unexpected things,” he laughs. “It’s not a bad place to end up really.”

Although Banks has had huge fun compiling A Chord Too Far, there’s no time for laurel-resting. “I had the honour of being commissioned to write a piece for the Cheltenham Music Festival and I have several other pieces that I’m working on. The tenor John Potter asked me if I’d set a couple of poems by [Elizabethan physician and lutist] Thomas Campion to music. I liked it because I didn’t have to write lyrics!”

There’s a tendency to view Tony Banks’ solo career through the lens of the success of his colleagues, but it’s important to judge it on its own considerable merits. Many people seem to want more Genesis – witness the success of Steve Hackett’s Genesis Revisited, the myriad tribute bands and the frequent requests for reunions. But A Chord Too Far has unexpected chord changes, indefinable melancholy, hooks and texture. Listening to Banks’ classical pieces especially is where you can find Genesis living and breathing today.

FOUR OF THE BEST: BANKSINGERS

Tony Banks on his favourite vocalists.