This article was first published in Classic Rock 34, December 2001, and is reprinted here in tribute to guitarist and founding member Brian James. Like he says in the article: “If things are flat and boring and you’re being programmed to be like your grandparents then something’s wrong. Something’s wrong if you’ve gotta spend all your life working for a fucking pittance. We just loved music and we just wanted to play. It was about expression - action, y’know? The fun was a bonus."

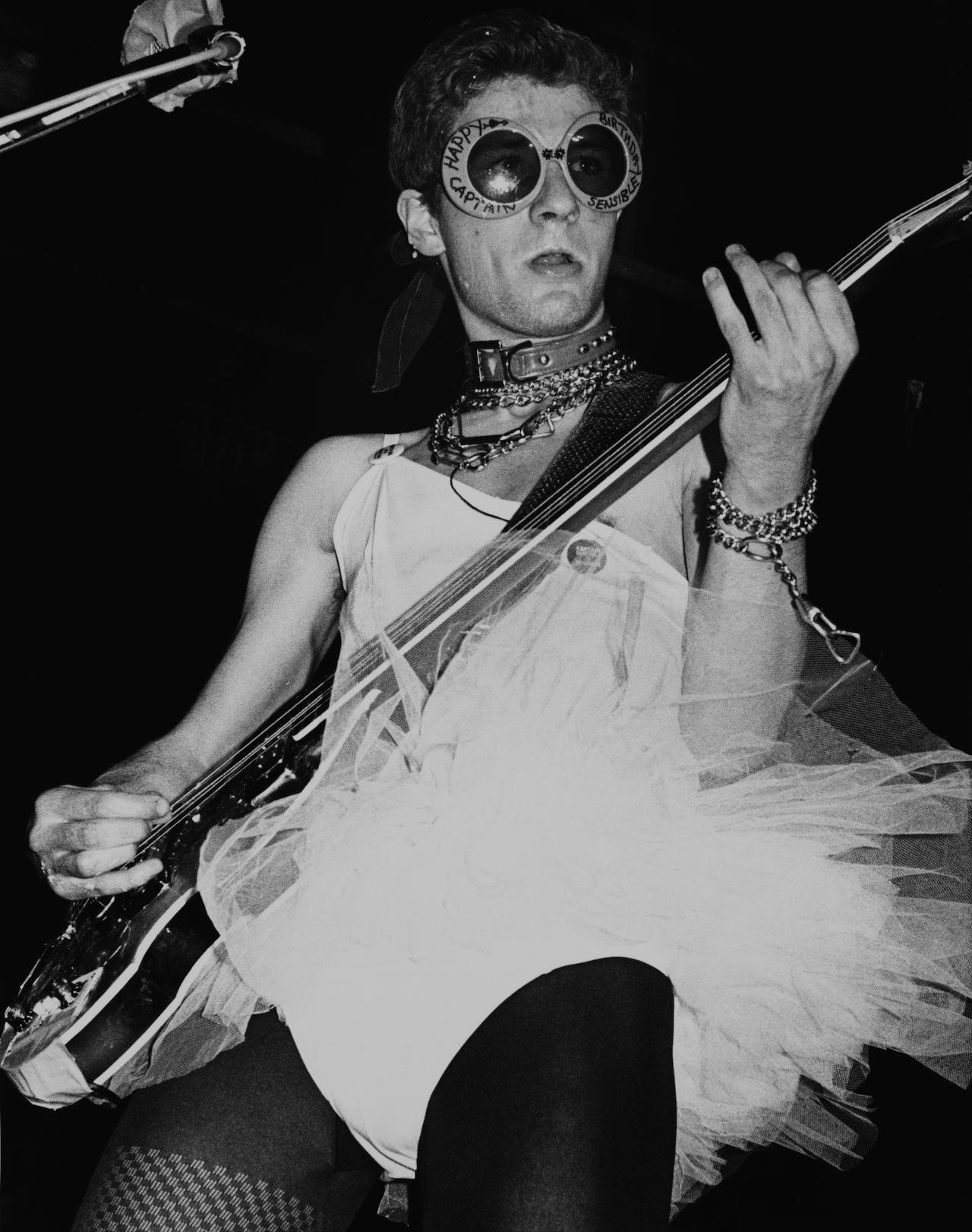

“At one point Lemmy came up to me and said, ‘I wanna have a word with you about your drinking’,” says Captain Sensible. “Well, when someone like Lemmy says that to you, you listen. He said, ‘Remember: it’s not what you drink, or how much you drink, it’s how fast you drink.’”

The Captain finishes his Grolsch and orders a glass of water. “I’m pleasantly surprised to have come through it and still be alive,” he says.

Welcome to an epic tale of fast living and faster music. The Damned were the first UK punk band to release a record, the first UK punk band to tour America, the first to split up (in 1978), and the first to reform, six months later (when the Clash were only on their second album).

They’ve had more line-up changes than Marlon Brando had hot dinners (with both Motorhead’s Lemmy and Culture Club’s Jon Moss joining briefly). Their guitarist became a red-beret wearing novelty pop star. They became synonymous with the 80s goth movement and dented the charts with Eloise. Along the way they’ve been shot at, beaten up, hoodwinked, spat on and chased around venues by three-legged dogs.

Meet Brian James, guitarist, songwriter and the man who was The Damned for a short while. “We used to do a fair bit of speed,” says Brian, “but we used to drink a lot so we needed it to stay awake.” He shrugs: “I like playing fast. I like playing loud.”

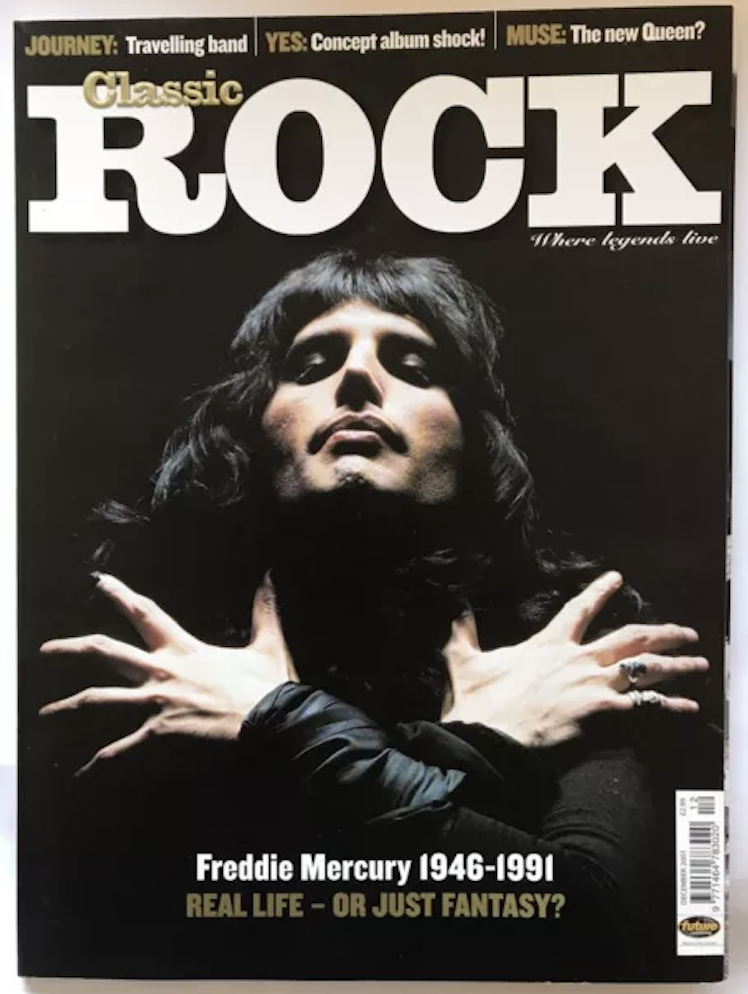

"I didn't want drink, drugs and women. All I wanted was the haunted mansion on the hill, with the bats flying around it..."

Dave Vanian

Meet Dave Vanian, vocalist and wannabe vamp: “People would ask you why you joined a band,” says Dave, “and other people would say, ‘Well, I want to drink as much as I can, take as many drugs as I can, fuck as many women as I can…’ and all that stuff. What I wanted was the haunted mansion on the hill. With the bats flying around it and the laboratory. And if I got a couple of girls inside of it, great…”

Meet Captain Sensible, sometime punk legend, novelty pop star and Damned bassist, guitarist and songwriter: “We had a saying in the band,” says Captain. “‘The first rule is: there’s no rules’. I’m a working class bloke. I genuinely was a toilet cleaner. Rat was a toilet cleaner. Dave genuinely was a grave digger.

"If someone comes up to me and says ‘Will you do an ad for Cheesey Wotsits?’ Am I supposed to say, ‘Fack off! I ain’t doin that shit! I’m gonna stand up for me principles, mate, fuck off! I don’t need that fifty grand!’ When I’m eating Pot Noodles, living in a council flat? I don’t think so. I’m like, ‘Gimme that cash!’”

Meet Rat Scabies, punk pioneer, hell-raiser and The Damned’s surrogate Keith Moon. “…….. ” says Rat. “ …….”. By all accounts, Rat isn’t normally this quiet. Rat, you see, has refused to be interviewed about The Damned, having had a bit of a falling out with the rest of the band over a small business matter.

A shame, but that’s The Damned all over: a tempestuous tale of gob, vomit, cider, sulphate, haunted mansions, Cheesey Wotsits, arguments, breakdowns and mad, bad and dangerously loud rock music.

The band's entry in the All Music Guide used to say: “The Damned weren’t revolutionaries, they were drunken louts that would do anything for a prank”. It’s a misconception that has done the band no favours over the years: while the Sex Pistols have been the subject of movies, TV shows, documentaries and books, and The Clash have had a posthumous number one and an Ivor Novello Lifetime Achievement Award, The Damned have been taken less seriously.

“We were outsiders even in the early days,” says Vanian, “‘cos we used to say what we actually felt rather than words that were put in our mouths. I always felt that The Clash’s political stance came from their management more than anything else. He [Clash manager Bernie Rhodes] seemed to have heard about how the MC5 did it in the 60s and decided to copy that. People were believing statements like ‘We’re only here for the kids’, when we’d hear them saying stuff like ‘Oh, when’s the limo coming round?’”

While Johnny Rotten poured negativity on everything (packaged up nicely, meanwhile, in Vivienne Westwood clothes) and The Clash tried their hardest to live up to a manifesto, The Damned were a whole other kettle of fish.

"We wouldn’t be hypocritical. We’d say we wanted money – it’d be stupid to say otherwise."

Dave Vanian

“We just adopted this persona of being as troublesome and chaotic onstage as possible,” Rat said later. This generally meant alcohol-fuelled destruction, nudity, vomit, reckless behaviour, verbal abuse and lashings of gob. The kinda stupid shit young working class people do, in other words.

“I was only interested in politics in terms of stirring things up,” says Brian. “If things are flat and boring and you’re being programmed to be like your grandparents then something’s wrong. Something’s wrong if you’ve gotta spend all your life working for a fucking pittance.

"We weren’t shouting about anarchy or giving it the big Clash number but that was never what we were in it for. We just loved music and we just wanted to play. It was about expression, action y’know? The fun was a bonus. We might’ve been larking about a bit onstage, but we were still coming up with the goods.”

They weren’t hypocrites either. “On the Anarchy In The UK tour [the short-lived punk tour with the Pistols, The Clash and Johnny Thunders],” remembers Dave, “we were in the back of a van, they were in four star hotels. We wouldn’t be hypocritical. We’d say we wanted money - it’d be stupid to say otherwise, y’know, we wanted to make a living - and in some sense that classed us as outsiders.”

Significantly, The Damned refused to go along with the idea that all the music that had come before punk was for hippies. “We refused to go along with the old farts thing,” says Vanian, “saying that all the older music was rubbish. We were only ever against the stuff that was rubbish.”

That said, the music scene at the time more sorely lacking in excitement. “In ‘76 there was nothing to listen to,” says Captain, a confirmed Santana and Hendrix fan. “I didn’t really like The Band and Little Feat and all that stuff. Clapton had gone down the toilet, and that slow country rock thing really wasn’t my cup of tea. And it was that or the Osmonds. So when the Ramones came along it was a revelation. All that ‘1-2-3-4’ stuff: that’s what it’s all about!”

“The charts were pretty crappy at the time,” remembers Dave who - as a teenager in Hemel Hempstead, got his kicks from 60s garage bands like The Seeds and Strawberry Alarm Clock, as well as early Gene Vincent, Alice Cooper and film music.

“I managed to see the New York Dolls when they came over back in ‘73 or ‘74. They were like a throwback to the ‘50s Shangri Las period. I thought Johnny Thunders was a great guitarist and of course Brian had come from a long line of those Keith Richards-y type guitar players.”

No-one in England would book us. We were just too fucking UP FOR IT for them.

Brian James

Guitarist Brian James had played at Phun City, the legendary 1970 festival in Worthing that had been the largest free festival in the UK. Headlined by hippy’s militant wing – the MC5, the Pretty Things, Pink Fairies etc – it had a huge influence on the young Brian. When his high-octane rock failed to land an audience in the UK, he took it to a more appreciative audience in Europe.

“I had a band previous to The Damned called Bastard and we were located in Brussels,” he says. “No-one in England would book us. We were just too fucking up for it for them. It was the aftermath of the hippy thing, pub rock – this would be like ‘73/‘74 – so we fucked off to Belgium where people were into the American bands like the Stooges, MC5, the Dolls, Lou Reed, all these good people…

“When I came back in ‘76 I teamed up with a couple of guys in England, Tony James and Mick Jones. They were trying to get a band going called London SS. And then we started auditioning people and I was just really, really surprised at the people coming out of the woodwork that were actually into that kind of music – there was no sign of them a year before.”

“I met Brian through an ad in Melody Maker,” says Captain. “He had vision. He had this plan of taking over the world through thrashy punk music. And he had a bunch of songs that were exactly what I wanted to hear. It booted butt, and there was nothing like it over on this side of the Atlantic.”

Brian had already hooked up with drummer Chris Miller, soon re-christened Rat Scabies when, at his audition for the London SS, a rat appeared in the rehearsal rooms. Miller had scabies at the time; his nickname was sealed.

“To me, punk was like a fucking dream come true,” says Brian. “Suddenly I was able to play these songs I’d written. Finding like-minded musicians: finding Rat was such a fucking *turn-on*, a drummer that wanted to play like I did. And then there was these guys we were getting introduced to called the Sex Pistols, and they were playing – not with the same musical flair – but with totally negative attitudes to all the hippy-dippy stuff that was still lingering about.

"Then Mick had teamed up with a couple of guys and they’d got The Clash together, Tony James had Generation X. There was a lot of attitude, bands forming and splintering and other bands forming out of that. It was a really exciting time for a while.”

Dave Vanian had been hanging around Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s shop, at that point called Too Fast To Live, Too Young To Die (later to become Sex). “I bluffed my way into the musical industry,” says Dave.

“I sang in my bedroom and realised that I could hold a note or two. McLaren was looking to put people together and I told him that I’d sang in some local bands. He liked the way I looked, I s’pose. I was all in black, but a little weirder looking. All made up, spikey hair and six inch tall granny boots: high lace up Victorian boots with massive heels.

"I suppose I used to look quite androgynous and I used to get loads of stick. I was forever getting into fights. It was a nightmare. When Captain was brought in he had all this corkscrew hair like Marc Bolan. I remember Malcolm saying, ‘I don’t wanna use ‘im - ‘e’s just a facking ‘ippy!’”

I was making a hell of a lot more money digging graves than I was with The Damned, I’ll tell ya.

Dave Vanian

While McLaren went off to manage the Sex Pistols, the nucleus of the Damned was formed. Brian asked Dave if he’d like to audition as singer. “I found out that there was another guy auditioning so I turned up early to see what he’d be like. He never turned up and I got the job.

"The weird thing is, the guy who never turned up was Sid Vicious. I often wondered whether, if he had showed up, he’d have become the lead singer in The Damned.”

Getting the gig meant Dave had to leave his job as a grave digger in Hemel. “I actually only did it to give me some time to think about what the hell I was going to do with my life,” he says. “But they offered me some perks to stay and stuff, and I was making a hell of a lot more money digging graves than I was with The Damned, I’ll tell ya.”

New Rose was released in October 1976, pipping the Sex Pistols’ Anarchy In The UK to become the first record released by a UK punk band. Stiff had rushed them into the studio to record the single and album before the Sex Pistols and the pace was matched by the music. It didn’t stop to mess around.

“The album was raw,” says Sensible. “It’s all first takes and hardly any overdubs at all. Fuelled on sulphate and cider, if I remember rightly. We knocked it out in two days with [producer] Nick Lowe. It doesn’t seem that fast nowadays, but at the time, people used to say, ‘Did you speed the album up?’ Ridiculous.

"But it’s raw and it doesn’t sound polished at all, compared to the Pistols stuff. I mean, take Rotten off and it could be Bad Company or somebody like that. Slow and turgid, I thought. We laughed when we heard Anarchy – couldn’t believe it.”

Rat’s pounding drums, Brian’s razor-sharp riffs and short squealing solos, Sensible’s manic driving bass lines and Vanian’s snarling vocals (his throaty gothic croon didn’t come until a couple of years later) created the sound of a band in a rush to get to the point (or, more likely, the bar). A frantic and furious British version of the Stooges and the MC5, it made The Clash look timid and the Pistols look turgid.

We laughed when we heard Anarchy In The UK – couldn’t believe it. Slow and turgid. Take Rotten off and it could be Bad Company.

Captain Sensible

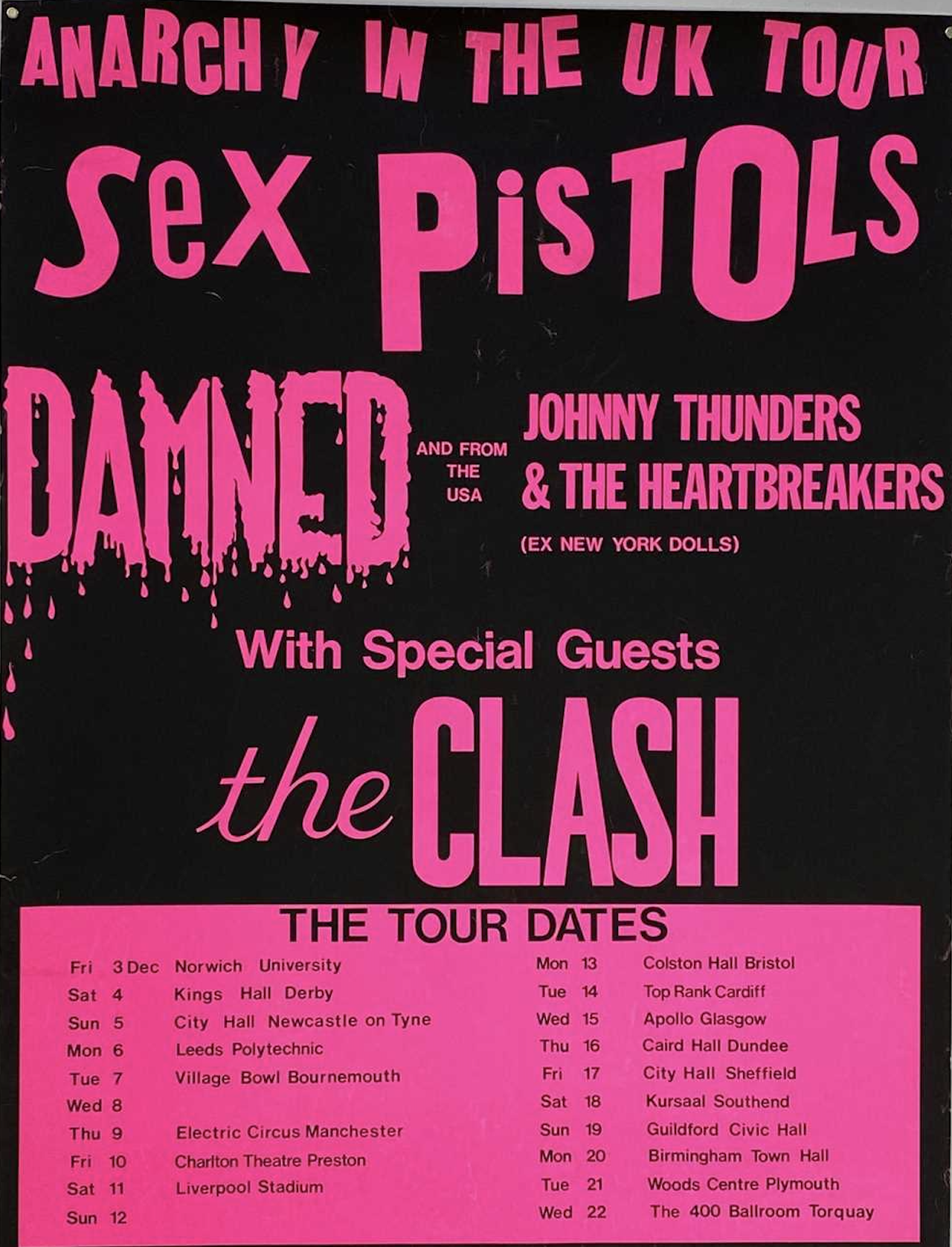

The single came out in October, the album was scheduled for February, and in between was the small matter of the Anarchy In The UK Tour with the Sex Pistols, Clash and Johnny Thunders and the Heartbreakers.

The tour started on the 3rd of December. By the 7th, the Damned had been thrown off and labelled ‘punk traitors’: in Derby, the council had refused to let the Pistols play, but said the other bands could. The Clash and the Heartbreakers refused, but the Damned were willing to consider it. And that made them sell-outs.

If you believe Malcolm McLaren’s side of the story, that is. “The truth is,” says Brian, “the only reason Malcolm wanted the Damned on the Anarchy tour was because the Pistols had hardly ever played outside of London. I don’t think the Clash had ever played outside of London, and we had. We had a bit of an audience going, so he wanted to make sure the Damned were on the bill otherwise 30 miles outside of London there’d be no-one there.

“The night before all the bands were doing a soundcheck when the Pistols came running in: ‘You won’t fucking believe it! We’ve just done The Bill Grundy Show… blah blah blah’. Laughing about it. The next day, it’s all over the fucking papers, Bill Grundy’s sacked, the whole thing."

The full effect of that kicked in two days into the tour. At that point, the line-up was the Pistols headlining, The Damned before the Pistols, and then Johnny Thunders and the Heartbreakers and The Clash on first.

“Two nights into the tour," says Brian, "Malcolm starts having a go at our tour manager. He was like an office boy at Stiff, he wasn’t an experienced manager or anything, he was just there to make sure we got to our hotels and stuff. We weren’t travelling with the rest of them. They had record company support: EMI, CBS and stuff like that. They had a big coach, we had a little Transit. We weren’t part of ‘the Malcolm McLaren gang’.

"So Malcolm gives this kid such a hard time, saying, ‘I don’t need The Damned’ and all this shit, that he’s in tears. So I steamed in and I had a go at Malcolm: ‘What the fuck are you on about?’ I didn’t give a fuck in them days, I was ready to fuckin’ hit ‘im to tell you the truth. But he had his bodyguards.

“So it comes to this big showdown. Malcolm wants The Damned to go on first, then Heartbreakers, then the Clash… It turned into this big political number. Meanwhile, the gigs were being cancelled because the promoters were getting the heebie-jeebies because of all the bad press.

"We’re getting all this crap from McLaren and there’s people contacting our office saying, ‘Will The Damned play anyway?’ We’d turn up somewhere like Manchester to find the gig’s cancelled, but they still want us: ‘Fuck it, we’ll do it’. What are we meant to do? Say, ‘Oh no, we’re not doing it! Not if our mate Malcolm’s not doing it!’? You know what I mean? I could’ve fucking killed that bastard!”

The incident as reported in the music press ruined some of the band’s credibility. Years later, in Jon Savage’s respected punk tome England’s Dreaming, it was still being distorted: The Damned weren’t good enough, The Clash wanted to be higher up the bill, The Damned couldn’t be trusted.

“Total nonsense. Him [Savage] and McLaren have re-written things,” says Sensible. “These people – they refuse to allow the rest of us any credit for dreaming things up or having intelligence. So of course, punk didn’t start in the bars down Portobello Road with the bands, it was McLaren and Vivienne Westwood. Nothing to do with us…”

The Anarchy Tour wasn’t the only tour the Damned got thrown off. A support slot with US rockers the Flamin’ Groovies was also short lived. “They couldn’t keep up with us, I’m afraid,” says Captain.

“We had banners made up that said ‘Gob now!’ And we’d hold the banners up behind the band we were working with. The audience, of course, would comply and the band would be absolutely covered in stuff. We had one support band, they got the whole fisherman’s outfits – sowesters, everything – and they wore them every night onstage! The Flamin’ Groovies didn’t approve! They’d never seen anything like it.

"There was another band that came over from New Zealand, called Split Enz. They had weird haircuts and funny clothes. In Australia they were shocking people by the way they looked. They came out on stage in the UK and the audience shocked them! Straight on the first plane back home they were. They were pretty manic days.

I wouldn’t have liked to work with us back then. It was dangerous. There was serious amounts of lunacy going on.

Captain Sensible

“I wouldn’t have liked to work with The Damned at the time, to be quite honest. It was quite dangerous, I’d imagine. To have come through it still alive… I’m not overstating it: There was serious amounts of lunacy going on. If the hotel was next to another building, we’d jump from roof to roof, pissed as parrots, just to get the flag off the roof. I’m scared of heights! The things you do when you’re paralytic…

The mania continued. For their second album, Brian decided he wanted a second guitarist. Rat and Captain disagreed. “We thought Brian could cover it,” says Captain. “When you’ve got that big wall of noise, you don’t need two of them doing it. Throughout the auditions we were doing everything we could to put people off.”

Like what? “Like spitting at them as they were auditioning. And we’d be playing with our trousers and pants down around our ankles, y’know, urinating on the floor, stuff like that.

"Out of the 30-40 people we saw that day, most of them didn’t even last one song. This character Lu gave loads back, he loved it. His name was Robert Edmunds, but we called him Lu, short for Lunatic. We were like, ‘Get that lunatic back, he was the only one that had any bottle!’”

The album, Music For Pleasure, recorded with Lu and produced by Pink Floyd’s Nick Mason (The Damned share a publishing company with Floyd – they were hoping for Syd Barrett), was a disappointment to the band, fans and critics.

Today, Brian blames the record company rushing them into the studio with half-finished songs, the posh studios it was done in, and the fact that the band were knackered. (Why didn’t they take a break? “They kept us on the road,” says Brian, “kept us working. They wanted the money coming in.”)

The album came out in November ‘77, their second in one year, and despite standouts like Problem Child, Stretcher Case Baby and Creep, it didn’t live up to expectations. On their UK tour that month, Jon Moss – better known later as the drummer for Culture Club – replaced Rat Scabies.

“Rat had a bit of a breakdown in France. He built a campfire in the middle of his hotel room. It was quite cute in a way,” laughs Brian. “Except that he’d drunk a bottle of brandy or something and was threatening to jump out the window. At that point, our only bit of normality was the three quarters of an hour on stage.

"It was only then that no-one was sticking stuff down our throats or up our noses. Offstage, people’d be… celebrating. And it’s hard to wind down when you’re not used to it. And I think it’d got to Rat. He’d partied hard, real hard.”

"We'd be spitting at them as they were auditioning, playing with our trousers and pants around our ankles, y’know, urinating on the floor..."

Captain Sensible

Jon Moss took over for the UK tour, but auditions for a permanent new drummer didn’t go smoothly. An old rocker who’d drummed with the likes of Gene Vincent and Eddie Cochran turned up. ““He had all these great stories,” says Brian, “and you don’t meet these people very often. There were all these drummers queuing up to do their bit - I did feel a bit sorry for them - but we left them waiting and went to the pub. For about two hours.”

Brian had lost interest: “I said to the other guys, ‘Look, I want to break the band up’. I don’t think the Captain was very happy about it. But it wasn’t working.”

“It was Brian’s baby,” says Captain now. “It was his vision and his songs that made us. And when that happens people say, ‘You’re the talent in this band, you don’t need the rest of them.’ I think people were saying that to Brian.

"I was pretty pissed off, to be quite honest. I could see the toilets beckoning. They’d said they’d keep me job open for me! I didn’t know what to do with myself. Six months later we got back together again, without Brian.”

Captain moved over to his first love, lead guitar, and they got a new bass player, Algy Ward, previously of Aussie punks The Saints. The remaining members, meanwhile, discovered a songwriting chemistry they didn’t know existed.

The Captain’s first attempt at a song was Love Song, a blistering two and a half minutes of punk pop thrash. It went to number 20. The resultant album, Machine Gun Etiquette is now thought by many to be their best.

“I think people thought we were washed up,” says Vanian. “The songwriter of our hit album, gone. Guitarist, gone. You’d think that was it. But Captain had always been a great guitarist and when we all started writing it was obvious there was a lot of chemistry there. We went in different directions and I think that’s what has kept the band alive, somehow: each album moves somewhere.”

1980’s The Black Album was double vinyl and a deliberate nod to the Beatles’ White Album. Neither as indulgent or as streaked with genius as the Fab Four’s creation, for a punk band it nevertheless pushed the boundaries. At 17 minutes, the epic Curtain Call filled a whole side of vinyl.

Keyboard wizard and soundtrack composer Hans Zimmer produced History Of The World Pt. 1. Dave Vanian, meanwhile, revealed himself to be one of the most distinctive and gifted singers of the era (“My voice dropped about an octave,” he says. “I could reach much lower notes than I had ever been able to previously. Consequently I wasn’t able to reach the higher notes either”).

Algy Ward was out, Paul Gray was in, and this time around they produced the album themselves on an old pig farm in Wales. “The record company said, ‘You can’t produce yourselves, it’s the kiss of death’,” remembers Dave.

“They were freaking out. They sent this guy down to hear the results, so we recorded a really terrible track – out of tune vocals and all this bullshit – and we arranged it so that as he pulled into the car park I was shooting a shotgun at one of the band as he ran off screaming, ‘I’m never fucking working in this band again!” The guy arrives in the middle of all this chaos, comes in and hears this terrible track, turns around and says, ‘Sounds great!’”

Despite a lack of commercial success, the band had hit a purple patch. Follow-up album Strawberries was even better: concise pop songs with beautiful melodies, great rock hooks, clever arrangements and brilliant production.

They switched record labels, lost and gained personnel (Roman Jugg joined on keyboards), but still the big hits eluded them. Well, not all of them. Captain Sensible’s version of Rogers and Hammerstein’s Happy Talk, recorded as a joke filler for a solo album he’d been working on, was released as a single in June ‘82 (months before the release of Strawberries). It went to number one and made Sensible a novelty pop star.

“I suppose it happens in other bands, but usually it’s not the guitarist it happens to,” says Captain. “Sounds had described me as ‘one of the world’s most disgusting slobs’. We were pretty rancid and disgusting and the joke was that I wasn’t the sort of person that should’ve sung a song like that. People were playing it for that reason at first and then it became a monster hit. A few months before it I’d done a single with [anarcho-punks] Crass! That was me. Happy Talk wasn’t.”

Over the next couple of years, tensions set in. “I thought we could co-exist, but I just didn’t realise it wouldn’t work,” says Sensible. “I remember a gig in north Wales where a limousine came and picked me up and whisked me off to do some promotional thing and the rest of them had to get in the back of some Transit van. It must’ve upset them.”

Vanian disagrees: “That never worried me,” he says. “All this bullshit of people selling out. If the TV people want to pay for some nice car to pick you up, why not take advantage of it? Why go on the bloody bus? Take it – it’s not going to last forever.

"To me, it was great ‘cos here was this great eccentric character, part of our British heritage, getting in the back of a limo going ‘Lend us a fiver. Ah, fuck you mate!’. The thing about Captain is: what you see is what you get. It’s not an act. He genuinely is a complete… weirdo.”

When his solo career took off, the good Captain was hitting the sauce pretty hard. “We used to have this thing called the 24 Hour Club,” he says. “If you went to bed you'd be ejected from the club. So the 24 Hour Club would sometimes run for four or five days, gambling all night, drinking, substances. The Ruts, the Damned – and a bunch of coke dealers – heh-heh, I didn't say that.

“So I ended up on kids TV several times, completely blitzed out of my mind. I remember Mike Read said to me on one Saturday Superstore: 'Captain, you seem to be on very good form this morning - why don't you sing us a tune?' I was like, 'I'll give you a tune!' I jumped on the table, tap-dancing, kicking everything all over the place, singing at the top of me voice. I slipped on the table, fell off backwards, banged me head on the studio floor and passed out. I was carried out by two blokes on a stretcher, live on Saturday Superstore. Completely zonked.”

Down but not out, The Damned made their biggest comeback yet. Their new material won them a major label deal with MCA, Roman Jugg moved on to guitar, and Grimly Fiendish a comic up-tempo Goth-meets-Madness number went to number 21 in the UK.

The Phantasmagoria album saw them flirt with goth (albeit a far more fun and melodic version than the po-faced doom of the Sisters Of Mercy or Fields of the Nephilim). It reached number 11 and was repackaged in 1986 when a single not on the album reached number two in the UK, their highest chart placing: Eloise, a cover of a 60s hit for Barry Ryan, and written by his brother Paul.

“I’ve got this short list of covers I’ve always wanted to do and that was on the list,” explains Vanian. “I liked Paul Ryan’s writing because it’s not as straight as you first think it is. On the surface they seem like sugary love songs, but really they’re all quite twisted songs about weird situations. The original lyrics of Eloise were banned by the BBC: it’s about an obsession he’d had with a stripper."

“It’s a sad story," he says. "When we covered it, I ended up on TV with Paul and Barry doing interviews, and it was great. Lovely guy. We rekindled his whole interest in writing and he went out and bought a keyboard and started writing again. He recorded some demos and it was the last work he ever did: he killed himself in a bout of depression. In fact, I have a demo of a song that he gave me which at some point we may do. It’s about John Lennon and it’s probably the last song he ever wrote.”

MCA rushed them into the studio for a follow-up, despite the band’s protestations. The result, Anything, was the worst album of their career: over-produced and lacking classic songs. For the first time, the band faced absolute disinterest from fans and record company.

MCA dropped them at the end of 1987, then began a series of reunion gigs. “Things really started to fizzle out for us,” says Vanian. “The MCA thing had ended and certain people in the band had got used to that kind of lifestyle. We just didn’t know where it was going.

As the popular music scene was gripped by grunge and then Britpop, The Damned seemed out of step. Vanian threw himself into his side project, The Phantom Chords, while Rat came up with a plan.

According to Vanian, the idea was to record an album of guitarist Allan Lee Shaw’s songs for release in Japan only. With the money from that, they’d go in to the studio and work on a proper Damned album. The album, Not Of This Earth was released in Japan and then America, against Vanian’s wishes but with Rat’s approval. It spelt the end of a long relationship. “I don’t bear any animosity towards Rat,” says Vanian. “We hadn’t spoken for a while but we do now. It took me a while to get over it though.”

Six months later, in February ‘96, the Damned were back together without Scabies, but with Sensible. Vanian’s partner Patricia Morrison, formerly of The Gun Club and The Sisters of Mercy, joined on bass. Years of gigging and songwriting paid off with a record deal with Dexter Holland of The Offspring’s Nitro Records.

The album, Grave Disorder, was an amazing return to form. So, Who’s Paranoid? followed seven years later. At the 2012 Classic Rock Awards, they won the Outstanding Contribution Award.

“Some people burn very brightly and then they dim for a while and then they suddenly come back better than ever,” says Vanian. “I don’t know if anyone has been consistently brilliant throughout their whole career – not if they’ve had a long career anyway. At the beginning you’re hungry, you’re broke… In some ways that hasn’t changed for us! Maybe that’s what gives us an edge.”

“Yeah,” says Captain, “I can’t think of any bands that’re absolutely stinking rich that make good music, can you? And we’ve always been brassic…”

The story first appeared in Classic Rock 34, December 2001