It’s February 1978 and Jim Henson is trapped. The mastermind behind the Muppets is snowed in at a Howard Johnson’s hotel in New York with his sixteen-year-old daughter, Cheryl. Most parents and children would be playing games or watching TV to pass the time; the Hensons are instead drafting a treatment for what would become the most controversial family fantasy film of all time.

The 25-page summary, entitled The Crystal, would be transformed across four years into The Dark Crystal - and would become the first true bomb of Jim Henson’s career. The mystical quest of a Gelfling creature called Jen fighting to save his planet from the corrupt Skeksis race proved too weird and dark for critics, many of whom had long boxed its writer/director/producer in as “the Muppet guy”.

A contemporary Time review wrote, “Audiences nourished on the sophisticated child’s play of the Sesame Street Muppets and the music-hall camaraderie of The Muppet Show may not be ready to relinquish pleasure for awe as they enter The Dark Crystal’s palatial cavern.” The New York Times echoed that sentiment: “Miss Piggy would not be kind to The Dark Crystal.” The box office reflected the critical lashings when the film only returned $41 million on a $25 million production budget and God-knows-what marketing spend.

Forty years after its theatrical release on December 17, 1982, however, The Dark Crystal isn’t a forgotten detour from a filmmaker better suited to swinging hand puppets next to celebrities. It’s the first true realisation of Jim Henson and his team’s talents, building a completely new universe rich in life, colour and imagination.

Inarguably, the greatest thing about The Dark Crystal is the backdrop in which its story takes place. The planet, named Thra offscreen, is home to such an inventive array of flora and fauna, all of which was created practically. The puppetry is so seamless and the sets so gargantuan that suspension of disbelief for a world so weird has rarely been easier.

Concept design for The Dark Crystal was handled by Brian Froud, whose 1976 collection of folkloric illustrations Once Upon A Time hugely impressed Henson. Such an art style was deemed perfect for The Dark Crystal, since the director envisioned the film as reviving the bleakness of the Brothers Grimm fairytales. “[Henson] thought it was fine to scare children,” his longtime collaborator and fellow Dark Crystal director Frank Oz later explained to The San Francisco Chronicle. “He didn’t think it was healthy for children to always feel safe.”

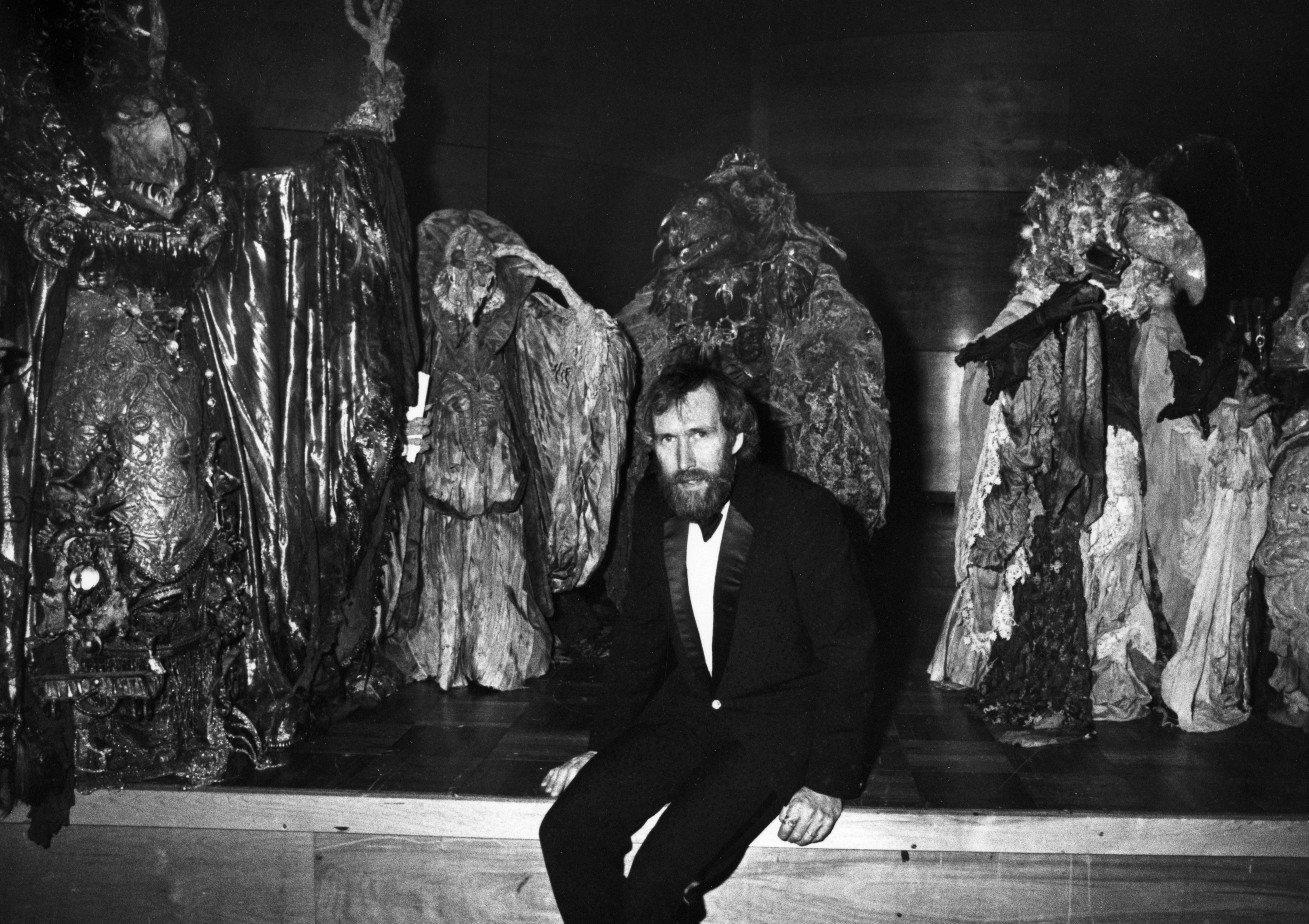

In that vein, the Skeksis became (in Froud’s words) “part reptile, part predatory bird and part dragon” and wore ghoulish Victorian regalia, inspired by a Leonard B. Lubin drawing depicting alligators in a palace. Such themes as death and corruption of the soul became cornerstones of the script. There were also other mature concepts integrated, like spirituality and the duality of man.

In a 2012 interview with Gizmodo, Dark Crystal screenwriter David Odell, who’d also worked with Henson on The Muppet Show and The Muppet Movie, spoke about how spiritual the puppeteer was. That personality trait manifested itself in the film.

“[Henson was] a spiritual searcher,” he said. “He had developed his own ideas that seemed to combine a little bit of theosophy, Hinduism, Taoism and various New Age philosophies. Before we started work on The Dark Crystal, he insisted I read a book called Seth Speaks.”

Seth Speaks was by Jane Roberts: a writer who claimed to be intermittently possessed by a multidimensional being. She apparently channelled that being, called Seth, while in a trance and recorded the words that came out of her. How insane all of this sounds is subjective, yet Henson was a big fan. He went so far as to use The Dark Crystal to communicate or respond to Seth Speaks’ ideas – even if, as Odell has claimed, he didn’t always understand them. The concept of the Skeksis having gentler counterparts called the Mystics, and the two halves reuniting into a hyper-intelligent race at the film’s end, echoes ideas in Roberts’ writing.

Unsurprisingly, the puppetry on The Dark Crystal was unprecedented in its complexity. People, animatronics, remote controlling or any combination of the three moved the film’s effects. The Mystics were the trickiest things to animate, according to Henson: the hunched-over, four-armed creatures required a puppeteer to crawl about while scrunching their body into a ball and holding their dominant hand out to control the head.

To offset the slow and hulking masses that were the Skeksis and Mystics, as well as the humanoid Gelflings, Henson made sure to also populate The Dark Crystal’s landscape with legions of smaller, faster and weirder animals. The diversity and scope together make the film’s world feel full: this is less a story than a slideshow of new settings, each rife with their own distinct life. It’s an exploration of the capabilities of puppetry with the intimacy and scrutiny of a Planet Earth episode.

Such commitment to world-building and character design is also The Dark Crystal’s Achilles heel. As wondrous a technical achievement as it is, this is a story that feels incomplete. The film’s opening is an onslaught of voiceover narration that has to explain the Skeksis and Mystics, the eponymous Dark Crystal and the fact it’s cracked, Jen’s parents being murdered and the orphan being adopted by a Mystic, and a prophecy that says the main character is “the chosen one”. How did the crystal crack? Who came up with that prophecy? It’s never said.

From there, the plot’s a cavalcade of new, unexplained developments. Jen can somehow use a flute to distinguish the real shard chipped off of the Dark Crystal from a number of fakes; he later meets another Gelfling who has inexplicable psychic powers, before they ride to the Skeksis castle on Landstrider animals that abruptly appear. It feels made up as it goes along.

The filmmakers seemed to be aware of this problem. Froud later said: “When we finished the film, we knew that we had only seen a fragment of this other world.” Thra would have been an ideal setting for a broader cinematic universe yet, before a sequel could be formally entertained, the film had to actually come out – which became a challenge.

During post-production, producer Lew Grade sold his company, ITC Entertainment, and the new management was apathetic towards the avant-garde puppet film they were presented with. In the end, Henson bought The Dark Crystal from ITC to ensure it was properly promoted.

Ultimately, less-than-stellar feedback and disappointing box office takings killed any prospect of a Dark Crystal 2 in its crib. Henson returned to safer ground by producing and starring in 1984’s The Muppets Take Manhattan, before dabbling in dark fantasy one last time with Labyrinth: a film that, identically to The Dark Crystal, baffled the mainstream and bombed before finding new life as a cult classic. It was Henson’s last directorial role before dying of toxic shock syndrome in May 1990.

Since then, there have been countless attempts to get a multimedia Dark Crystal universe off the ground. Froud co-wrote three prequel comic books, published between 2011 and 2015, before four novels came out from 2016 to 2019. Then, in August 2019, Netflix released a series called The Dark Crystal: Age Of Resistance. The ten-episode show maintained the puppetry and practicality of its source material, and also allowed the world more time to be explained. Although almost everyone that watched it fawned over it, Netflix cancelled Age Of Resistance after just one season: the expense and time needed for puppet animation likely wasn’t compensated by the viewing figures.

After all this time, there are still gaping holes in the tapestry of The Dark Crystal. However, even as the foundation of a mythos that never was, the film has aged beautifully. On a technical level, it remains Jim Henson’s crowning achievement.

The Dark Crystal: Age Of Resistance is out now via Netflix