Few rock stars have had the power, presence or charisma of The Doors or their frontman Jim Morrison. From Patti Smith and Joy Division to The Cult, Jane’s Addiction and Stone Temple Pilots, the late singer and his bandmates have inspired countless artists who followed.

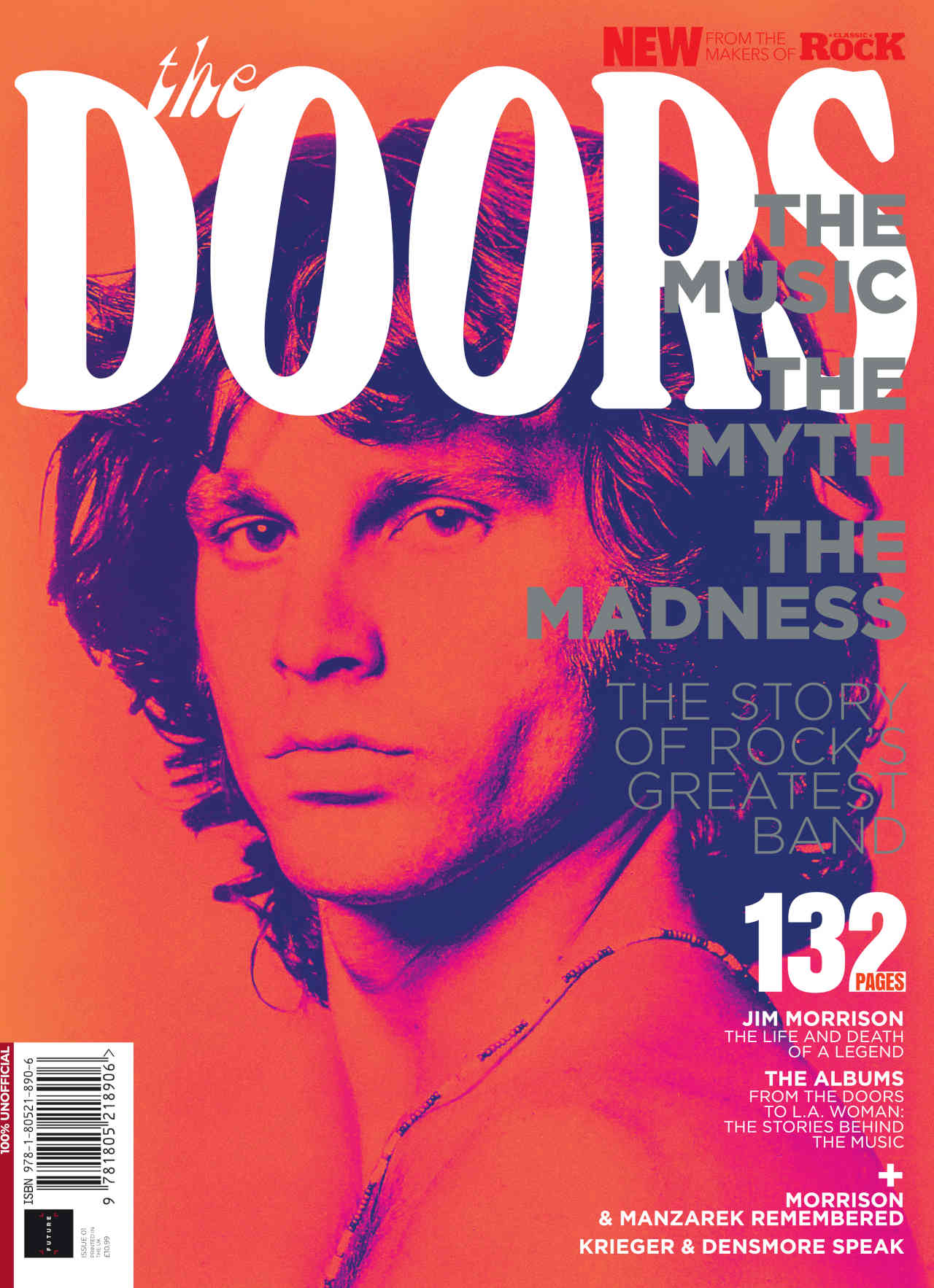

That legacy is celebrated in Classic Rock: The Story The Doors, a special 132-page magazine dedicated to this most influential of bands. Drawing from the Classic Rock archives, it charts the story of The Doors from the clubs of LA to superstardom in the late 60s and early 70s, taking in key points along the way, including in-depth looks at the making of the six studio albums they released before Morrison’s untimely death in 1971 at the age of 27.

In this retrospective feature, originally published in 2018, the singer’s friends and associates look back on the making of the band’s classic penultimate album, Morrison Hotel.

The end of the 1960s found The Doors – one of the dark-star American groups who had exemplified the freewheeling spirit of that groundbreaking yet troubled decade – teetering on the abyss. With Jim Morrison increasingly becoming the victim of his own hype – drunk and out of control most of the time, a danger to himself and others – the rest of the band feared for their own futures.

“The boys did not hate Jim,” insists former Doors tour manager Vince Treanor. “The boys did not dislike Jim. The boys wanted Jim to be part of the group, but they couldn’t take the trouble that Jim was causing. They couldn’t take the loss of [so many] performances as a result of his behaviour. They couldn’t take the loss of all the record sales. They couldn’t deal with the loss of radio time. The censure that went down, the newspaper articles, the pastors and the righteous ministers with their boyfriends in the closet that got up and were saying how terrible The Doors was and how perverted Morrison was. The whole thing. They didn’t want to deal with that kind of bad, negative, horrible publicity.”

And yet, in the drawn-out aftermath of the arrest of Doors frontman Morrison after he allegedly pulled out his penis on stage at a concert in Miami in April 1969, ‘bad, negative, horrible publicity’ followed The Doors around like a cloud of flies.

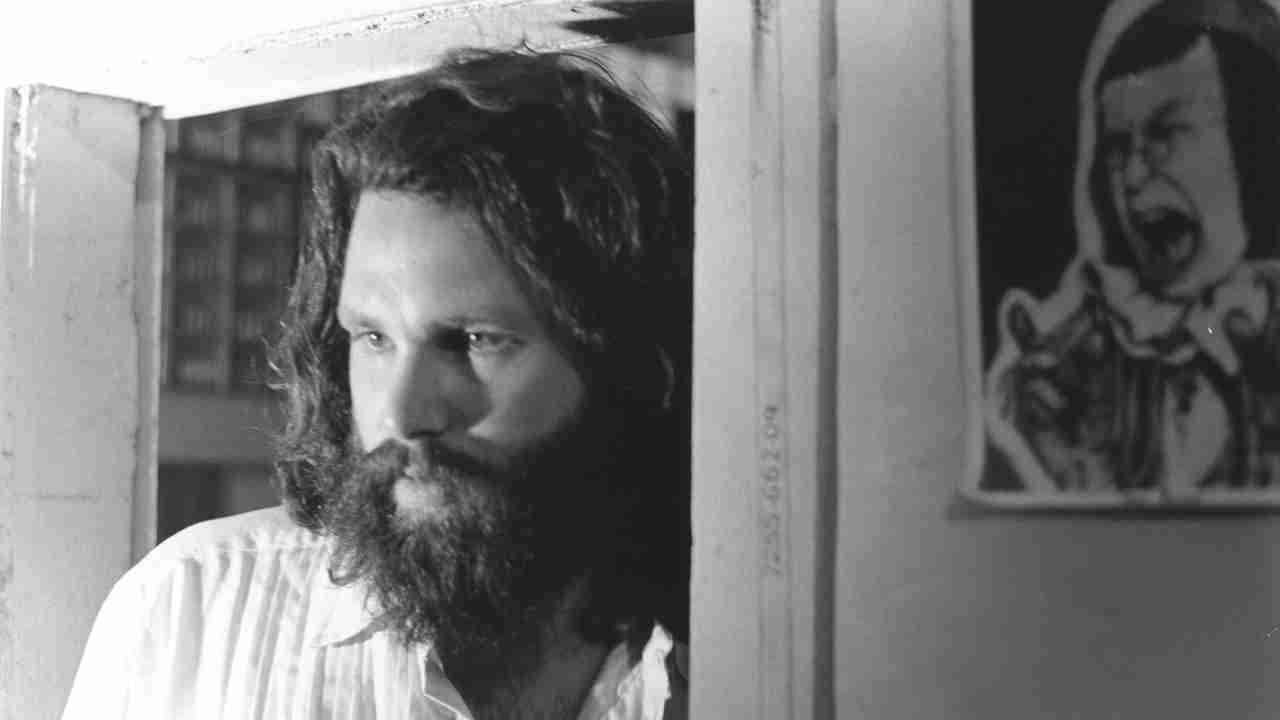

The release later that year of The Doors album The Soft Parade, an overindulgent confection of lyrical navel gazing and musical self-importance, had not helped the band’s sagging reputation. Jim Morrison was now a bearded and bloated parody of the lit-up boho poet he still saw himself as, while keyboard player Ray Manzarek, guitarist Robby Krieger and drummer John Densmore were way past long-suffering, and now deep into despair about their rapidly shrinking career prospects. Suddenly everything about The Doors was a drag, man.

“As Jim got more out of control – the roomful of gunpowder waiting for somebody to light a match – Ray became more alienated and isolated from him,” Treanor says. “Now Ray never disowned Jim, but he never did what we all should have done, which was to say: ‘Look, asshole, smarten up, you’re wrecking everything!’”

Treanor recalls how Morrison once told him: “People wanna see me drunk on stage”. “I said: ‘Nobody wants to see you do that. They want to see a Doors performance. They do not want see you lumbering around the stage drunk, forgetting your words and putting on a show where you stand there babbling nonsense. Put on a Doors show, sing Doors music, stop the nonsense, because it’s only gonna hurt!’”

Indeed, as 1969 ended the hurt seemed to be coming down on everyone. America was still waging war in Southeast Asia. Britain was still crumbling, while Europe remained aloof. In rock, the dream as personified by Woodstock in August – an event from which The Doors were pointedly absent because, according to their manager Bill Siddons now, “they exclusively headlined and did not want to be one of many”, but which Robby Krieger once explained away as being because they thought it would be a “second-class repeat of the previous year’s Monterey Pop Festival”, a decision they came to regret – had turned into the nightmare of the Rolling Stones’ free outdoor show at Altamont Racetrack in December, where 18-year-old Meredith Hunter was stabbed and clubbed to death by Hells Angels.

In the same period, the Charles Manson murders and subsequent arrests had transformed LA from fun-loving and free into a city of paranoia. People – affluent music and movie people especially – now carried guns in their cars. With cocaine and heroin replacing weed and acid as the drugs du jour, the new ‘heavy manners’ under which America in general and LA in particular operated made Morrison’s antics before and after Miami seem suddenly, weirdly in tune with the times. As he sang on a new thing he’d written: ‘Blood on the streets of fantastic LA…’

Such was the backdrop to the recording of the fifth Doors album, originally titled Hard Rock Café, before being changed to the more enigmatic Morrison Hotel (Side One would still be billed on the sleeve as Hard Rock Café, Side Two as Morrison Hotel). The story of which really began when Elektra Records founder Jac Holzman stepped in with a plan to rehabilitate the public image of The Doors.

“It was not over before Miami, but it could have been over after Miami,” Holzman tells me now. “John [Densmore] was disgusted. They didn’t know what to do. They were being blacklisted in large auditoria around the country, and they said: ‘What are we gonna do?’ I said: ‘Time to make another record. Go into the studio. Work out your demons in the studio.’ And Morrison Hotel came out of that. Not the easiest record, but it was stuff that Jim was comfortable with and there was some really fabulous material. So that was the right thing for them to do, because I knew [Miami] was gonna blow over eventually and they would go out on the [road] again.”

First, though, Holzman suggested, they should play two special high-visibility shows in LA, from which they would extrapolate a live album – a kind of feel-good bridging exercise to get the people and the press back on side again, and show the promoters what they’d been missing during the still ongoing ban. “Which became the backbones of Absolutely Live.”

For two nights, July 21 and 22, The Doors would take over the Aquarius Theatre on Sunset Boulevard, where the stage musical Hair was then playing, and put tickets on sale for just two dollars a pop.

“That was an incredible performance,” says Holzman. “See, I wanted them in front of a friendly audience again. Because they had been really shaken, and I thought they would get their sea legs back more quickly if they were in front of a friendly audience. And the only way I could guarantee that was to produce the concerts ourselves.”

In the weeks that followed the Aquarius shows, the band got to play three more concerts – in San Francisco, in Eugene, Oregon, and Seattle Pop – where they appeared on the same bill as Led Zeppelin. But any hopes of this being the start of a return to touring in the US were quickly dashed when projected shows in Toledo, Philadelphia, San Diego and New York were ‘rescheduled’.

Meanwhile, work in the studio on the projected live album wasn’t going any smoother. Doors producer Paul Rothchild, now heavily into cocaine and at his most tunnel-visioned, was insisting the group come in and overdub the many dozens of parts he had identified as inadequate, either because of malfunctioning equipment or simply because he thought the band should have played better.

According to Treanor: “Everybody was a victim. It wasn’t one of them, all four had to get their dibs in there. But it was during that session that Paul introduced the cocaine. I was appalled. I got out of there…”

The Absolutely Live album was eventually released almost a year later, several months after Morrison Hotel, and in completely revamped form.

Meanwhile, The Doors played their final show of 1969 on November 1 at the aptly named Ice Palace in Las Vegas, a large, anonymous hockey arena in Nevada, where the audience had little or no interest in hearing anything from The Soft Parade and only really came alive when drummer Densmore cracked open the start of Light My Fire.

Morrison, though, sleepwalked through the show. A week later he was obliged to turn himself in to the Dade Count Public Safety Dept in Miami, where he was officially arrested, gave The Doors’ office in LA as his home address and entered a not-guilty plea. The presiding judge, Judge Murray Goodman, set the bond at $5,000 and 20 minutes later Morrison was free to go – on condition that he return for the start of his obscenity trial, now set for April 27, 1970.

Although advised by his lawyer, Max Fink, to keep a low profile, two days later Morrison was in trouble with the law again, during a Continental Airlines flight from LA to Phoenix to see the Rolling Stones in concert. His crime this time: getting drunk and out of control and harassing airline staff and other passengers. Both Morrison and his travel companion, Tom Baker, were arrested by US Marshalls as soon as they stepped off the plane at Sky Harbour International Airport, and charged with the federal offences of ‘assault, intimidation, threatening a flight attendant, interfering with the flight of an intercontinental aircraft and public drunkenness’. When a knife was then found on Baker, the pair were taken straight to city jail where, they spent the night.

According to Baker, speaking years later, “Jim handed me a bottle of whisky and waved a fistful of choice front-row tickets around. He planned to stand outside the auditorium [where the Stones were playing] and randomly hand them out to young fans who couldn’t afford a ticket, saying: ‘This is courtesy of your old pal Jim Morrison. Enjoy the show.’ He felt this would be a good-natured and harmless way to upstage Jagger and company.”

The following morning, Max Fink flew into town, where he arranged with Bill Siddons, also in town for the Stones show, for Morrison and Baker to be bailed on $5,000, with an arraignment set for November 24. Driving back to the airport with Fink and Siddons, Morrison was told that if convicted, the charges held a $10,000 fine and a possible 10-year jail sentence.

The next day, Morrison was back in the studio recording material for the next Doors album.

The big idea was the same as everyone else’s in late 1969: to get The Doors ‘back to the garden’. That is, far away from the manicured musical cathedral of The Soft Parade, and back to their earthy blues roots.

Two months earlier, the second album from The Band – the roots-rock revivalists who had earned their spurs backing Bob Dylan through his last significant tours in 1966 – had been released and now sat at No.2 in the US chart. The most frequently played ‘rock’ record on the radio was their single Up On Cripple Creek. The Beatles, having ditched the orchestrated super-pop of Sergeant Pepper in favour of a return to their roots with the more grounded rock of Abbey Road, released in the US in October 1969, and preceded by the pointedly retro single Get Back, also appeared to be signalling the way back to a more ‘real’ musical state of mind. Meanwhile, Dylan retreated so far back into the history of rock that he’d ended up releasing an album so square – Nashville Skyline – that critics found it hard to believe he wasn’t putting them on.

The Doors, though, had a more pressing need for a return to simpler, less bombastic music than that which Paul Rothchild had coerced them into on The Soft Parade. Simple blues and balls-out rock was all Morrison could manage now. He simply didn’t have the attention span – or the voice – any more for anything more sophisticated or time consuming. Nevertheless, the sessions were uphill all the way, engineer Bruce Botnick recalls.

“Some of it was real tough, yeah” he says. “That was a concentrated effort to get away from Soft Parade and back to the roots. But even then that was a struggle… Many was a time when Ray, in particular, would go into Jim’s poetry book, see something interesting, do some editing, and sit with the other two guys and they’d come up with an arrangement. Jim might have a smattering of a melody… I mean, it still kept going, but it just wasn’t that block of creativity from Jim.”

Paul Rothchild, meanwhile, might have been ready to accept that the experimentation of The Soft Parade had not proved a hit, but he deeply resented having to try to work with a Jim Morrison who had always been a loose cannon in the studio, but in the past had also at least been able to come up with songs, lyrics and melodies, and to sing them well. Now he was simply a dishevelled drunk, as far as Rothchild could tell.

It was getting to the point where he couldn’t stand to be in the same room as Morrison any more. Rothchild had “grown tired of dragging The Doors from one album to another, especially an unwilling Jim, and he had virtually dried up. Two out of three times, Jim would either not want to work or would go into the studio drunk. He would intentionally disrupt things – never fruitfully. Most of my energies were spent trying to co-ordinate Jim with the group.”

Doors manager Bill Siddons recalled one session where Morrison came to rehearsals and drank 36 beers. Ray Manzarek would confess: “The situation was dire.” He and the rest of the band had come to realise at last that “Jim was an alcoholic”. Manzarek tried to qualify it by pointing out that, as far as he knew, “a genetic predisposition to alcoholism ran in his family. It was hard to tell him to clean up his act”.

Nevertheless, attempts were made. One afternoon during the Morrison Hotel sessions, Manzarek, John Densmore and Robby Krieger drove Jim over to Krieger’s father’s house and sat him by the pool for “a chat”. According to Manzarek: “We told him: ‘This is seriously affecting us all now as a group, and you physically.’ Jim says: ‘I know. I drink too much and I’m trying to quit.’ Which was a rare admission. We told him we’d help. Jim said: ‘Thanks. Now let’s go get some lunch at the Lucky-U. I want some funky Mexican food and a drink.’ That was Morrison. The romantic poet who wrote ‘I woke up this morning, got myself a beer’. A real ‘fuck you!’ line. Unfortunately that was the reality. Jim’s attitude was always: ‘Look out, man, I’m hell-bent on destruction.’ We couldn’t moralise. We figured he might emerge from the spiral. But working with Jim in the studio was the only way we knew how to transcend his problem.”

What they eventually came out of the studio with was, paradoxically, the most ‘up’-sounding Doors album of them all. Opening with Roadhouse Blues, featuring the wailing harmonica of an uncredited John Sebastian and the ass-tight bass of veteran rockabilly star Lonnie Mack, here was Morrison and the band opening up to where they were at in a way that is both fun and faintly disturbing. It would become the band’s new show opener and road anthem throughout the coming months as The Doors returned fitfully to full-time concert commitments.

Other new tracks worth the wait included Peace Frog, a funky hunk of LA shimmy that found Krieger punching out one of his most memorable riffs as Morrison scatted wildly about ‘Blood on the streets…’ of New Haven, of Chicago, on a river of sadness, and of fantastic LA, the lyrics for which Paul Rothchild found in one of the notebooks Morrison had left lying around the studio – while he disappeared to the nearby bar the Phone Booth for drinks – in a rough poem headed Abortion Stories.

Other highlights were Blue Sunday, a tremulous love song to Morrison’s long-time lover Pamela Courson, or maybe Judy Huddleston, or maybe Eve Babitz, or maybe that chick he’d fucked the other night at the Whisky A Go Go. It didn’t matter, the song was tender and sweet. Then there was Queen Of The Highway, one of the last truly great Morrison/Krieger numbers: electric jazz piano, snake-hipped guitar, rain-spattered percussion, and Jim’s voice, honeyed again, suddenly, his lyrics exquisite. It showed just what The Doors were still capable of, where they might yet go, if only they could keep their singer from setting himself on fire.

Others were repurposed or older tracks, the most lovely, Indian Summer, a moment of quiet transcendence constructed from the dying embers of The End, as if Morrison had chosen to love his brothers and sisters instead of killing his father and fucking his mother; Waiting For The Sun, revisited from the original 1968 sessions, now dated yet still moving enough to hold sway on an album rippling with new hope. Others still were wonderfully wrought facsimiles of great tunes The Doors might have come up with all on their own had they the collective willpower left to still accomplish such feats, but were cut and shut together with great skill by Paul Rothchild, whose raging perfectionism was nevertheless once again driving them all slowly mad.

There were also lowlights: Land Ho!, another dated-sounding, ‘ironic’ take on the traditional sea shanty, which fills up four minutes of the listener’s life that they would never get back; Ship Of Fools, yet another variant on the riff to Break On Through (To The Others Side), which could, equally, have turned up on either of the first two Doors albums.

Another gem was The Spy, its title and subject matter ‘borrowed’ by Morrison from Anaï Nin’s novel A Spy In The House, in which the heroine, Sabina, plays deliberately dangerous games of desire, intoxicated by the principle of pleasure for its own sake. Morrison knowingly croons about ‘your deepest, secret fears’ on what is one of the most truly autobiographical songs on the album

Outside the studio, however, time was now running out for Morrison and The Doors. When he and Baker failed to turn up for their scheduled court appearance in Phoenix on November 24, and instead sent Max Fink to register their joint not-guilty plea, Judge William Copple went ahead and set the trial date for February 17, 1970, in the US District Court in Phoenix. With the Miami trial date set for just two months after that, Morrison was looking at a potential joint jail time of more than 13 years

Nevertheless, he blithely carried on. When Henry Diltz shot the photographs that would be used on the cover of Morrison Hotel, he at least had a for-once clean-shaven Morrison to try to make look pretty.

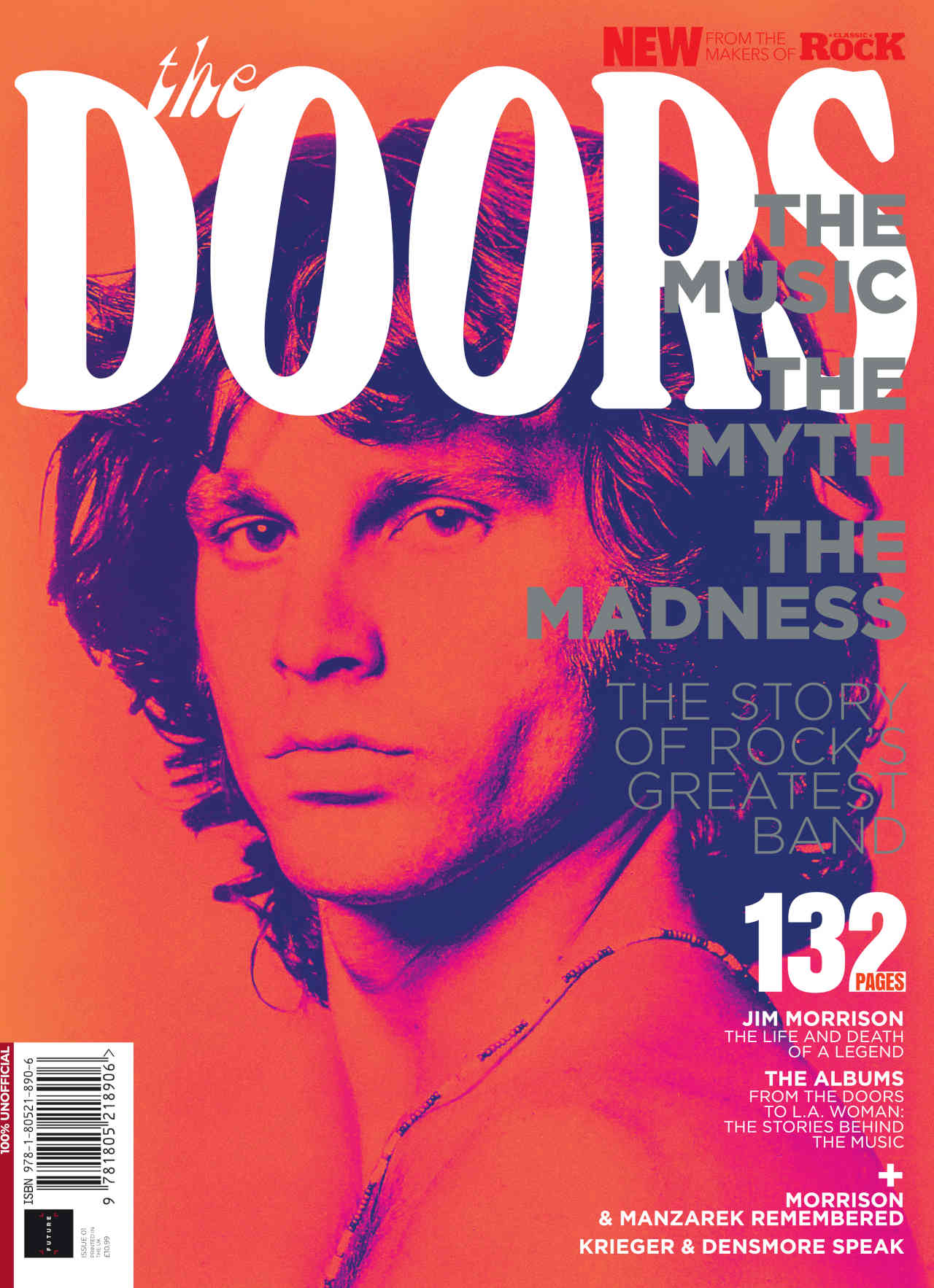

They had actually found a real-life Morrison Hotel, in the skid-row section of downtown LA (at 1246 Hope Street, to be precise) to go with the real-life Hard Rock Café at 300 East 5th Street, and Diltz photographed the band at both locations, going guerrilla to get some shots when the owner of the actual Morrison Hotel refused permission for them to shoot inside, getting the band to pose hurriedly when the manager’s back was turned.

In fact the real reason why Morrison had taken to shaving again – albeit temporarily – was because Max Fink had talked him into it, in order that he look the part of the successful, clean-cut young musician when the trial in Phoenix came up in February. That strategy that went disastrously wrong when clean-shaven Morrison turned up in court with Tom Baker – who had recently grown a full-length beard – and the flight attendant got the two mixed up, with the result that Morrison was the one found guilty of all charges, rather than Baker who had been the real perpetrator. It took several weeks for Fink to persuade the court of the mistaken identity, during which Morrison and Baker fell out after Baker refused to stand up and admit the truth to the court.

It all came to a predictably drunken head during a party at Elektra Records celebrating the opening of a new office in West Hollywood, when Baker accused Morrison of being a hypocrite for “financing the very authority you claim interest in overthrowing”. Morrison’s response was to shove Baker over a desk and proceed to start smashing up the new office. He was eventually bundled into the back of a limo, the driver being shouted at to “Get him the hell away from here!”

By the time Morrison Hotel was released, in February 1970 – and to their best reviews since their first album three years before – The Doors had announced their arrival back on to the American concert stage with four shows over two sold-out nights at the Felt Forum in New York, a 4,000-capacity adjunct to Madison Square Garden, chosen because of its resemblance to the more intimate feel of the Aquarius Theatre in LA. These shows would again be taped by Rothchild, still searching for the perfect Doors performances for their projected live album.

Billed as the Roadhouse Blues tour – a shrewd move designed to signal the new, bolder, hard-assed direction The Doors were now moving in – the Felt Forum shows were seemingly a triumphal return to form. At least while the party mood lasted. Which for Morrison was never quite long enough any more.

He now travelled with his own entourage, separate from the rest of the band, and when his mood altered from set to set no one was sure any more what the cause was, although the other band members could always hazard a pretty accurate guess, depending on just how fucked-up their singer was: on coke he could still be a defiant presence, ready to play for longer than contracted, making with the jokes and the moves, giving it his all, or what was left of it; on booze and downers he would be verging on the incoherent, “just holding on to the mic some nights”, Manzarek would later recall.

Reviews of the shows were varied. “Mr Morrison has had trouble before when the police of other cities found his performances variously lewd, lascivious, indecent and profane,” began the piece in The New York Times. “But by the standards of the Off-Broadway stage, Mr Morrison’s performance is fairly tame. Saturday he kept his clothes on and made no gestures that could offend.” The Village Voice, however, early adopters of the Morrison mystique, went for the kill, describing an off-stage sighting of Morrison a few nights later at a John Sebastian gig at the Bitter End club as “a shadow of himself, with his face grown chubby, his body showing flab, his once shoulder-length hair receding into his forehead”.

There were six more Roadhouse Blues shows in February, all around the release of Morrison Hotel, which was much better-received than its two predecessors. Creem magazine editor Dave Marsh described it as “the most horrifying rock and roll I have ever heard. When they’re good, they’re simply unbeatable”, while Circus announced it as “possibly the best album yet from the Doors… good hard, evil rock”. It went gold within three weeks, reaching No.4 in the US, their best chart position for two years. This despite the lack of a recognisable hit single from the album. You Make Me Real was issued to American radio, but in an era where singles were becoming increasingly frowned on by ‘serious’ rock fans, the fact that radio hardly played it, favouring instead deep cuts from the album, such as Peace Frog and Roadhouse Blues, only made the band prouder. The Doors were hip again, and resisted suggestions that the track Waiting For The Sun was a hit waiting to happen.

There were 13 more Doors shows around the United States throughout the spring and early summer of 1970, with Paul Rothchild turning up to record several of them. Quality varied so much that the band could go from world-conquering giants for half a set in Boston, to teetering on the brink of self-destruction again in Baltimore, where Morrison was so drunk that he could barely move his lips.

Even when The Doors were good there were problems. At Cobo Arena in Detroit, on May 8, they played brilliantly for more than four hours – the encore of The End lasted almost an hour alone, with Morrison improvising madly – yet found themselves banned from ever playing there again because they had overrun the teamsters’ union-set curfew time. Another promoter cancelled a show in Salt Lake City less than 24-hours before show time, after he had attended the previous show in Boston where the promoter had pulled the plug when the band overran and Morrison could be heard to describe them as “cocksuckers”.

Somehow, Morrison Hotel, the actual and the personal, would not be a place where guests would stay for long. But they would rarely, if ever, forget it.

This feature appears in Classic Rock Presents: The Story Of The Doors. Order it online and have it delivered straight to your door.