1969 had been a monumental bummer for The Doors. The year had taken a turn for the worse in April, when Jim Morrison had been arrested for allegedly pulling out his cock onstage in Miami. The ensuing storm had seen lucrative tours cancelled, while the album that followed in July, the pseudo-sophisticated The Soft Parade, was their worst-selling. More worryingly, Morrison had ballooned in size, hiding his dazed face behind a huge beard.

There had always been a canyon-wide difference between the way Morrison – self-styled tortured poet – thought of The Doors and how the other three members of the band – the actual musicians – saw themselves. By 1969, the gulf had opened up to the point where the others couldn’t stand the sight of their singer any longer.

Producer Paul Rothchild had become the man whose job it was to chivvy the band into action, and it was wearing thin. “I’d grown tired of dragging The Doors from one album to another, especially Jim [who] had virtually dried up. Jim would either not want to work or would go into the studio drunk. Most of my energies were spent trying to co-ordinate Jim with the group.”

Even keyboard player Ray Manzarek, who’d always been Morrison’s biggest cheerleader, was weary of pretending that the singer’s out-of-control behaviour was central to the band’s artistic expression. Years later, on interview autopilot, Manzarek was still insisting: “Jim Morrison was the shaman… The shows were rituals.” Well, maybe in the early days. But by the end of 1969 the shows were becoming a joke – and Manzarek knew it.

In a last-ditch attempt to salvage something from the situation, Elektra Records president Jac Holzman stepped in. “It could have been over after Miami,” Holzman says now. “John Densmore was disgusted. They didn’t know what to do. I said: ‘Time to make another record. Go into the studio. Work out your demons in the studio.’”

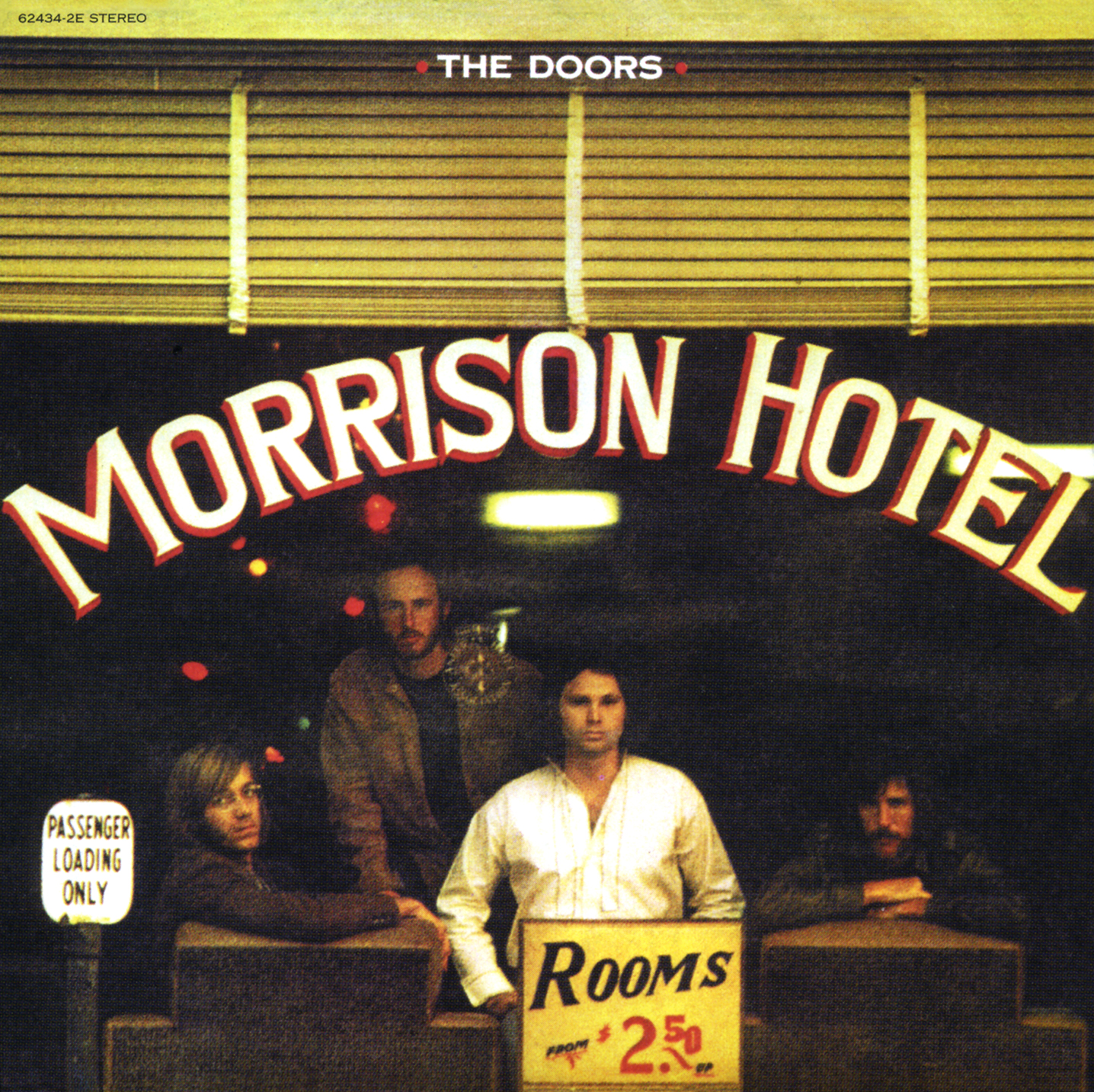

The result, Morrison Hotel, the fifth Doors album, would be both the most underrated of their career, and the one that put The Doors’ story back on track. By then, though, it was almost too late.

The last Doors show of 1969 had been at the Ice Palace in Las Vegas, on November 1, where the crowd only came alive when Densmore cracked open the beat to Light My Fire. Morrison, with more pressing things on his mind, had sleepwalked through the concert. A week later he would turn himself in to the Dade County Public Safety Dept in Miami, where a trial date for his onstage arrest earlier in the year was set for April 27, 1970, along with a bail bond of $5000.

Two days later, though, he was in trouble again, arrested as he disembarked from a Continental Airlines flight from LA to Phoenix. Along with his equally fucked-up companion, the former Warhol actor Tom Baker, Morrison was charged with “assault, intimidation, threatening a flight attendant, interfering with the flight of an intercontinental aircraft and public drunkenness”.

Taken to county jail, the following morning The Doors’ lawyer Max Fink arranged bail of $5,000, with an arraignment set for November 24. Driving back to the airport, Morrison was told that if convicted, these were federal charges that could result in a $10,000 fine and a 10-year jail sentence.

The next day Morrison was back in LA working on Morrison Hotel. The others barely mentioned Phoenix. They were more concerned with getting him to work while they actually had him in the studio. But things did not look good.

Unlike earlier Doors albums, where Morrison came in with the bulk of the lyrics and melodies already written, now Manzarek was forced into ransacking the singer’s journals and notebooks for ideas. “Then he’d sit with the other two guys and they’d come up with an arrangement,” recalls engineer Bruce Botnick. “There just wasn’t that block of creativity from Jim.”

Morrison was more preoccupied with his nights carousing on Sunset Strip than with his days lolling around the studio, sucking on a beer. He had his own corner booth at the Whisky, where he would get so drunk he’d start yelling about “fucking niggers”. The chicks would coo into his ear, but he would pour beer over the girls’ heads and then come on all sad and sorry afterwards.

One of those girls was Pamela Des Barres, who’d known Morrison since his pre-fame days. She recalls Morrison basically living at the Whisky during this period. “Blotto, you know?” she says. “He would climb up on stage with whoever was up there and interrupt their set and pull his pants down… They’d have to drag him off.” She laughs, then stops. “He was funny and he was deep, and things had meaning for him. He cared. But then I watched him fall apart through the years.”

She recalls coming out of the club one night in late 1969 and finding Morrison curled up in the gutter. “People were stepping over him. That’s what had happened to his mystique.”

According to the band’s then-manager Bill Siddons, Miami had been the breaking point for the singer. “For the first few years he was the ringmaster,” he says. “Then all of a sudden it was taken out of his hands and he was fighting for his life. And he just kind of went, I can’t do that any more. I don’t wanna do that any more.”

Or as Jac Holzman puts it: “Jim was now in another world. He had separated from the rest of us because he had to.”

Meanwhile, work in the studio continued fitfully. As Holzman explains, the big idea for the album was the same as everyone else’s in 1969: “To get back to their roots.” The second album from roots-rock revivalists The Band sat at No.2 in the US chart. The Beatles had also made a “return to the garden” with the earthy rock of Abbey Road, and the pointedly retro Get Back single.

The Doors had a more pressing need for a return to less complicated music: simple blues and balls-out rock were all Morrison could now manage. Bill Siddons recalls one session where Morrison drank 36 beers. “The situation was dire,” Manzarek later confessed. “Jim was an alcoholic.”

And yet the result, paradoxically, found The Doors’ music experiencing a new ‘up’. Opening track Roadhouse Blues, featuring the wailing harmonica of an uncredited John Sebastian, was both fun and faintly disturbing. ‘Woke up this morning and got myself a beer,’ Morrison sang. And then another, and another…

The real gold was found in tracks like Peace Frog, a funky hunk of LA shimmy. Rothchild had found the lyrics in one of Morrison’s notebooks, in a poem roughly headed Abortion Stories. Other highlights were Blue Sunday, a love song that could have been to long-suffering live-in lover Pamela Courson, or maybe to the chick at the Whisky Morrison that had fucked the other night. He couldn’t remember. Another, Queen Of The Highway, was one of the last truly great numbers he would write with Robby Krieger: electric jazz piano, snake-hipped guitar and Morrison’s voice suddenly honeyed again, his lyrics exquisite.

Others were repurposed or older tracks. The most lovely, Indian Summer, was a moment of quiet transcendence constructed from the dying embers of The End. The most dated-sounding, Waiting For The Sun, had been revived from the original 1968 sessions, yet was still moving enough to hold sway on an album trembling between hope and terror.

Rothchild was still tinkering with the final mixes in December, but by then the rest of the band was quietly confident that Morrison Hotel was the return-to-form they needed to help expel the horrors of the previous nine months.

When Morrison Hotel was released in February 1970 it rekindled the band’s commercial career. Circus announced it as “possibly the best album yet from the Doors… good hard, evil rock.” It reached No.4 in the US and achieved their highest chart placing in the UK: No.12.

But time was now running out for Jim Morrison and The Doors. A trial date for the singer’s arrest after the flight to Phoenix had been set for February 17, 1970. The date for the trial for the Miami arrest was two months later. Morrison was potentially looking at combined jail time of 13 years or more. “Can you imagine?” Ray Manzarek later said. “This was not flipping the bird to the cops, this was not some kind of protest, this was serious jail time.”

If there was any good news, it was that The Doors were now free to roam the country again. They announced their arrival back on to the American concert stage with four shows over two sold-out nights at the Felt Forum in New York, a 4,000-capacity adjunct to Madison Square Garden. The party line was that it had been chosen because of its more intimate feel. In reality it was because of fears that any repeat of the Miami incident would result in an even bigger riot.

The Doors may have been back on the road, but there was very little intimacy left between Morrison and his bandmates. He now travelled with his own entourage, separately from the rest of the band, and his mood altered from set to set. On coke, he could still be a defiant presence, making with the jokes and the moves, giving it his all – or what was left of it. On booze and downers, he would be incoherent, “just holding on to the mic some nights”, as Manzarek recalled.

“The boys wanted Jim to be part of the group, but they couldn’t take the trouble that Jim was causing,” insists former Doors tour manager Vincent Treanor III. “As Jim got more out of control, Ray himself became more alienated and isolated from him. But Ray never stood up to Jim and said: ‘Okay, man, toe the line, or else!’”

Morrison now had his sights set so low that nothing looked like up to him. He escaped serious censure over the rap for the Phoenix flight, getting away with just a heavy fine. But the Miami trial date had been put back again, to August, leaving the sword still hanging over his head. Meanwhile, Pamela Courson worn down by the ever-present gang of so-called friends and hangers-on that followed him everywhere, was hanging out with her new heroin-dealing boyfriend, the Count de Breteuil, while telling her friends Morrison was “a fag” who only ever wanted to fuck her in the ass.

It seemed like nothing was going right for the singer. The publication of his first book of poetry – an amalgamation of two self-published volumes from the previous year, with the conjoined title The Lords And The New Creatures – was overshadowed for the increasingly gloomy singer by the fact that no one outside of Rolling Stone magazine reviewed it.

His hopes of building a film career had hit the skids. Over the past year Morrison had met with several directors to discuss possible mainstream acting roles. But Hollywood execs who had thought they might be getting the new James Dean now found themselves confronted by a grossly overweight, mumbling drunk with a huge black beard and permanent midnight eyes. And then, just when things surely couldn’t get any stranger, Morrison decided to get married – to a witch.

Patricia Kennealy was a 24-year-old former go-go dancer and Mensa member who had begun an on-off affair with Morrison 18 months before. Petite, red-haired and formidably intelligent, Kennealy was also a Celtic Pagan high priestess and minister of the Universal Life Church – not the run-of-the-mill ‘chick’ Morrison was used to bedding. Utterly beguiled by each other, the two were married at her New York apartment on June 24, 1970 – mid-summer’s night – in a “hand-fasting” ceremony. Jim told her: “I never felt anything like it, not even on acid.”

Over the years since then, Kennealy, Celtic Pagan wife of Jim Morrison, has undergone ridicule, disbelief or simply been called an outright liar – she doesn’t give many interviews any more. Yet Morrison, the man who invited his audiences to “let the ceremony begin”, who told anyone who would listen in 1970 that he intended to “start a new religion”, was fascinated by her.

Kennealy puts Morrison’s obvious physical decline down to “the pain he was having to deal with. He really had put on a mask but the mask got stuck to his face. He couldn’t get out from behind it. And that was what he was trying to escape from with the alcoholism and all the other nonsense.”

By the time the trial in Miami began on August 6, 1970, Morrison’s pain had become all-consuming. None of the other Doors showed up to support him. Through it all, Morrison sat alone, drawing sketches of the jurors or openly reading a book, as if he already knew the outcome and was ready for it. He did, but he wasn’t.

On August 28 The Doors flew to England to appear at the Isle of Wight festival, for which Morrison got special dispensation from the judge. The Doors hadn’t played in Britain since their Roundhouse shows two years before. Expectations were high. Also on the bill were other members of the 60s cultural elite, such as The Who, Miles Davis, Joni Mitchell and others. As far as the band were concerned, all they needed was for the real Jim Morrison to show up and all would be right.

Instead, the Morrison who appeared on stage at the Isle of Wight was someone only previously glimpsed through the gloom long after the show was over. Not the Morrison who ranted and raved at audiences, nor even the Morrison who hung on to the mic stand for support as he slurred his way through songs. This was a dead man. Robby Krieger later recalled it as being “one of the worst shows that I remember”.

Watching from the wings, Vincent Treanor III shudders at the memory. “It was like somebody had poured a poultice on him and it froze, you know? There was no emotion in the singing. No movement of his body. Terrible! Shameful.”

It was the beginning of the end. “After the Isle of Wight,” Treanor reveals, “the decision was: we’ll never play on stage with you again. So the spectre of the future was already hanging over them.”

Forty-eight hours later, Morrison was back in court in Miami. When the verdict was finally delivered on October 30, he was found innocent of the charges of public drunkenness and of lewd and lascivious behaviour, but guilty of indecent exposure and open profanity. The judge gave him the maximum punishment: a $500 fine and six months in Raiford Prison, the most feared jail in the country. He was put on $5,000 bail and ordered back for sentencing in November.

His lawyers appealed, and sentencing was postponed until the New Year, by which time Morrison had fled to Paris. There he would receive an even more terrible sentence.