"We were so fired up to go on before Jim checked out that we didn't acknowledge his death and grieve": When the music's over - the story of The Doors' strange afterlife

The death of talismanic frontman Jim Morrison in 1971 looked like it marked the end of the road for The Doors. But his bandmates had other ideas

Select the newsletters you’d like to receive. Then, add your email to sign up.

You are now subscribed

Your newsletter sign-up was successful

Want to add more newsletters?

Every Friday

Louder

Louder’s weekly newsletter is jam-packed with the team’s personal highlights from the last seven days, including features, breaking news, reviews and tons of juicy exclusives from the world of alternative music.

Every Friday

Classic Rock

The Classic Rock newsletter is an essential read for the discerning rock fan. Every week we bring you the news, reviews and the very best features and interviews from our extensive archive. Written by rock fans for rock fans.

Every Friday

Metal Hammer

For the last four decades Metal Hammer has been the world’s greatest metal magazine. Created by metalheads for metalheads, ‘Hammer takes you behind the scenes, closer to the action, and nearer to the bands that you love the most.

Every Friday

Prog

The Prog newsletter brings you the very best of Prog Magazine and our website, every Friday. We'll deliver you the very latest news from the Prog universe, informative features and archive material from Prog’s impressive vault.

The lizard king is dead, long live The Doors. It’s August 1971, barely a month after Jim Morrison was found dead in a bathtub in Paris, and his surviving bandmates in The Doors are putting the finishing touches to their first album without him. You might politely call this an act of professionalism. In less charitable terms it could easily appear plain cold.

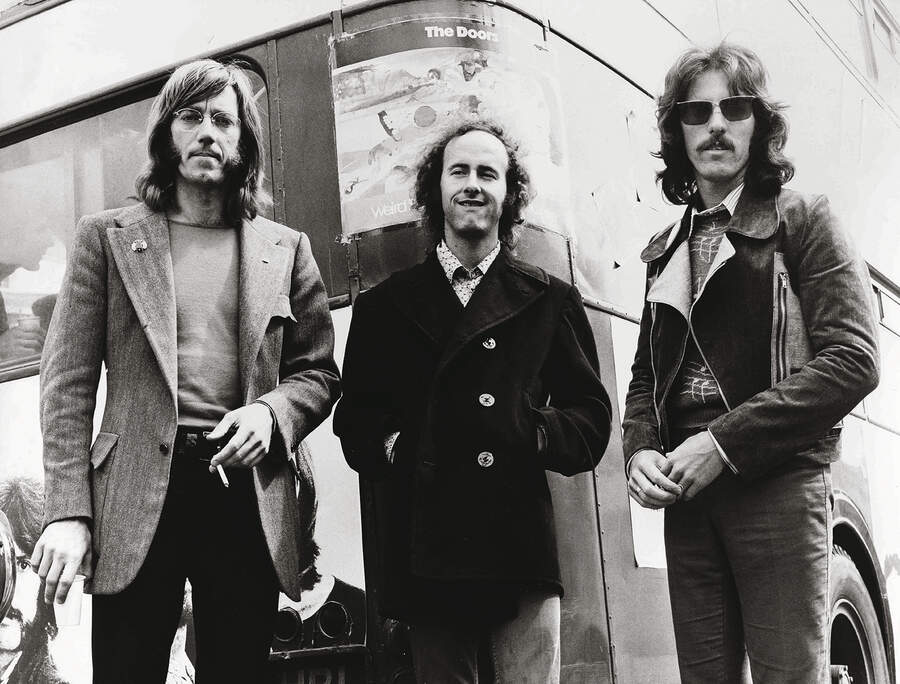

Incredible as it might seem, at that time there hadn’t been a whole lot of debate about whether or not to carry on. “Of all the mysteries surrounding The Doors, the one that maybe confounds people the most is why we thought we could still be a band after Jim died,” guitarist Robby Krieger wrote in his 2021 memoir Set The Night On Fire. “It seems so ridiculous now, but there was some logic to it.”

To be fair, there was more than a little logic to it. Krieger, keyboard player Ray Manzarek and dummer John Densmore had been writing and preparing songs for the next Doors album, while Morrison vacationed in Paris. According to Manzarek, Morrison had even rehearsed a number of new Doors songs prior to leaving for France. His non-return wasn’t viewed as quite the artistic crisis it seemed. “At the time it made sense to write songs,” Krieger reasoned. “It made sense to record. Our label was behind us all the way…Why not keep it going?”

In retrospect, the trio conceded that they should’ve allowed a period of mourning. But, as Densmore rationalised in his own biography Riders On The Storm: “We were so fired up to go on before Jim checked out that we didn’t really acknowledge his death and grieve.”

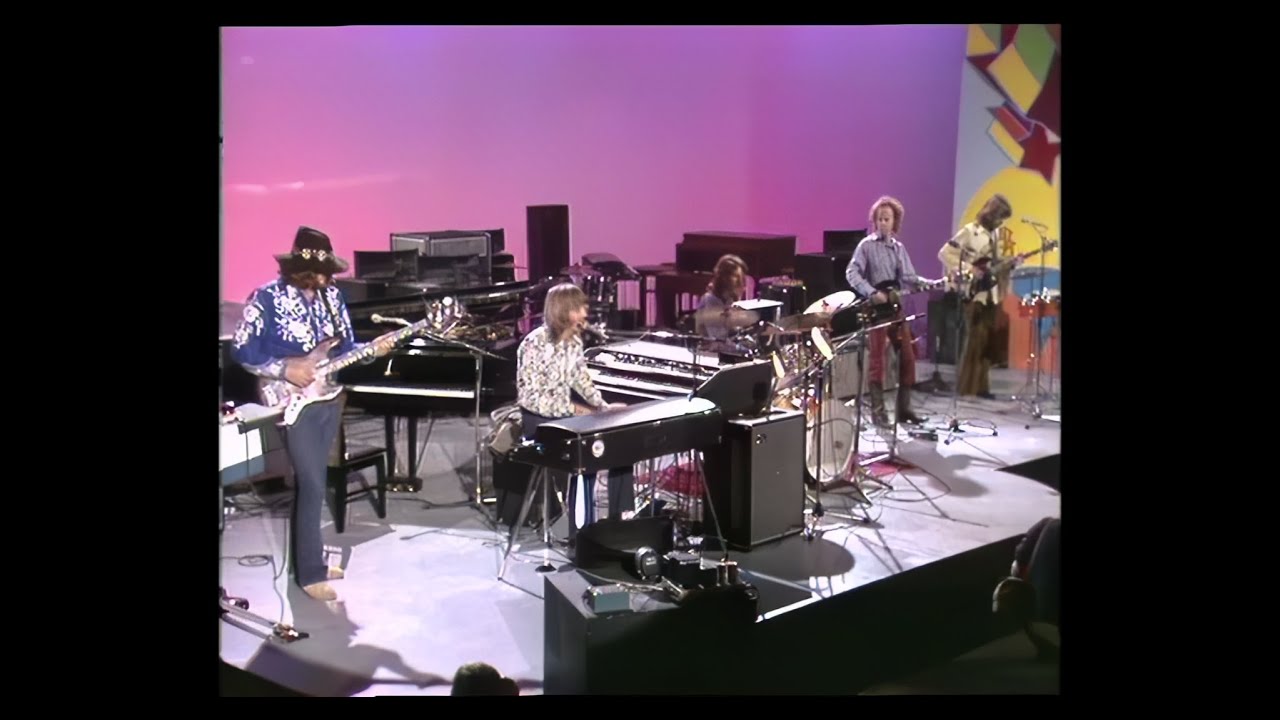

The immediate fruit of their labour was the album Other Voices. None of the band seriously entertained the idea of finding a replacement for Morrison, so they decided among themselves that Manzarek and Krieger would share lead vocals. Manzarek at least had form in this department, having sung in pre-Doors outfit Rick & The Ravens. The rest of the set-up was pretty much business as usual. Regular producer Bruce Botnick was at the controls, and recording took place in the familiar surrounds of The Doors Workshop, site of the L.A. Woman sessions, in Hollywood.

Notwithstanding the enormous Morrison-sized hole, Other Voices’ other major difference was its team of bassists. Jerry Scheff returned from L.A. Woman, but shared the bass playing with Jack Conrad, Wolfgang Melz and Ray Neapolitan. The songs, at best, were serviceable. At worst, The Doors sounded like a workaday bar band.

Krieger’s Variety Is The Spice Of Life, for example, quickly lapses into deadweight boogie, hardly enlivened by trite lyrics: ‘All these pretty women with nothing to do/C’mon and help me try to find something new.’ I’m Horny, I’m Stoned sounds just as bad as its title suggests; Down On The Farm - supposedly rejected by Morrison during the L.A. Woman sessions – can’t seem to decide whether it wants to be Canned Heat or a country pastiche.

Sign up below to get the latest from Classic Rock, plus exclusive special offers, direct to your inbox!

There are some worthy moments, however. Tightrope Ride rattles along like prime Stones. Lyrically it feels aimed directly at the band’s departed frontman, acting as both tribute and cautionary tale. There are allusions to isolation, madness and courting danger, while the final verse draws comparison to another doomed young soul: ‘We’re by your side, but you’re all alone/ Like a Rolling Stone, like Brian Jones.’

Hang On To Your Life finds The Doors locating their classic groove, underpinned by Melz’s sprightly funk bass line. The track accelerates, ultimately racing headlong into a manic jam. The epic Ships With Sails is similarly striking, not least for an extended instrumental passage that finds the trio truly inspired, negotiating folk-rock and jazz, and crowned by a great, open-ended Manzarek solo. It’s telling that Other Voices’ choice moments tend to be without vocals.

Released in late October ’71, the album couldn’t compete with its platinum-shifting predecessors, but peaked, fairly respectably, just outside the Billboard Top 30. Elektra Records boss Jac Holzman announced sales of 300,000, which, bolstered by a successful US tour that included sell-out dates at Carnegie Hall and Hollywood Palladium, was enough to warrant more studio time.

“[Jac] wasn’t naïve enough to think a Morrison-less Doors album would break any sales records, but he stood by us like he always had,” noted Krieger. “His undying support was, for better or worse, one of the big reasons we had to the guts to press forward.”

For better or worse, indeed. The trio wasted no time in recording a follow-up. This time The Doors opted to produce the album without Botnick, and brought in the highly respected Henry Lewy – best known for his work with Joni Mitchell and Crosby, Stills & Nash – as engineer. In turn, Lewy enlisted a clutch of session players that included another round of guest bassists, percussionist Bobbye Hall, jazz sax supremo Charles Lloyd and backing singers Clydie King and Venetta Fields. The scenery changed too, albeit none too radically, The Doors switching base from the Workshop to A&M Studios a couple of miles away on N. LaBrea Avenue.

The resulting Full Circle didn’t veer very far from its immediate predecessor. Again, Manzarek and Krieger split lead vocals. And while it’s patently unfair to compare either to Morrison, both men’s singing abilities are limited, however much spirit they try to inject. They’re hardly saved by the music, either. Get Up And Dance, with The Flying Burrito Brothers’ Chris Ethridge on bass, quickly descends into a generic chug. ‘Golden days!’ goes the lyric, as if attempting to convince themselves that they’re onto a good thing, despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

Hardwood Floor doesn’t help The Doors’ rapidly sliding reputation either. Here, Manzarek riffs away on rinky-dink piano like he’s playing for change in the saloon of some Western theme park. On Good Rockin’, a cover of Roy Brown’s jump-blues standard made famous by Elvis Presley as Good Rockin’ Tonight, he goes all Jerry Lee Lewis on piano while Krieger sets about channelling Scotty Moore. The less said for 4 Billion Souls’ excruciating call for world peace, the better.

Yet Full Circle also deserves credit for daring to experiment a little. The Mosquito, the album’s sole three-way co-write, offers a playful and unexpected burst of mariachi, complete with recurring hook, handclaps and party ambience. It was inspired by a holiday that Krieger and his wife took to Baja in Mexico, where they were serenaded one evening by a bunch of local musicians.

“They had a song about a mosquito that I wanted to learn,” the guitarist recalled later. “But when I got home I couldn’t quite remember it, so I wrote my own mariachi-sounding tune with simple Spanish lyrics.”

The Doors lean into it with such gusto – swirling organ runs, a Densmore drum break, jazzy outro – that you can almost forgive Krieger for rhyming ‘mosquito’ with ‘burrito’.

Full Circle packs a couple more surprises in Verdilac and The Piano Bird. The former takes a detour into New Orleans jazz-funk, dominated by Manzarek’s organ playing and Charles Lloyd’s tenor sax. The Piano Bird follows in similar vein, led out by Krieger’s light, rhythmic guitar figure. There’s a loose, carefree air to it all, with Lloyd’s jazz flute high in the mix, perhaps suggesting an unexpected way out of The Doors’ post-Morrison malaise.

Released in August ’72, Full Circle fared worse than Other Voices, peaking at No.68 in the States. Both albums hardly registered at all in other countries, despite the novelty success of The Mosquito in random parts of Europe, where it became a Top 20 single. It’s instructive to note that Krieger dispenses with both albums within two pages of his memoir. Densmore is even more dismissive in Riders On The Storm, washing his hands of both in just a couple of paragraphs.

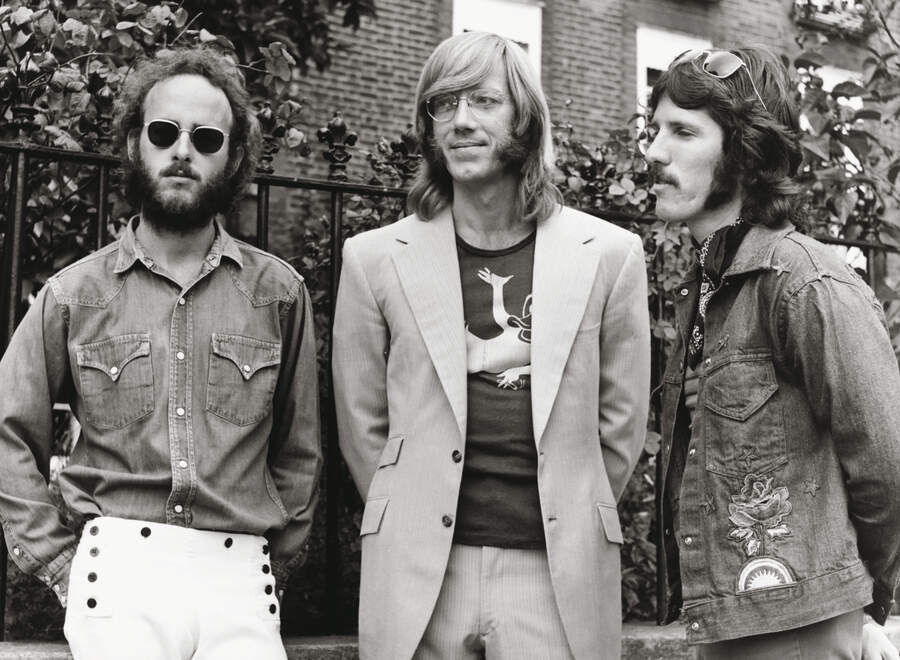

The Doors were still a decent live draw, through. So much so that, following their subsequent tour of Europe, they flew to London in early 1973, with the express purpose of finally bringing in a new frontman. They weren’t after a Morrison copyist. Instead, as Krieger put it, they wanted “someone who could theoretically take us in a bold new direction”.

Paul McCartney, Paul Rodgers and Joe Cocker were among the names brainstormed in The Doors’ hotel room. Contrary to rumour, Morrison disciple Iggy Pop was never in contention. A front-runner soon emerged in the shape of Howard Werth, who’d recently forsaken art-rockers Audience for a solo career. “I came on the scene because Jac Holzman wanted to make Audience the new band on his Elektra label,” Werth told Classic Rock in 2014. “But after we broke up he decided to try to put me and The Doors together.”

Werth had already started work on his first solo record, King Brilliant, but agreed to take part in rehearsals with Krieger, Manzarek and Densmore in West London. “Those rehearsals were quite strong and powerful,” he recalled. “We were just ploughing through. It wasn’t a matter of them suddenly turning round and going: ‘Oh, that’s good’ or ‘You’re the one’. We were just enjoying it and waiting for the situation to happen or not. And, as it turned out, it didn’t.”

Manzarek duly flew back home with his wife Dorothy, who was pregnant and miserable in England. But not before he had rowed with Krieger and Densmore over the musical direction of the band. In simple terms, Manzarek wanted more jazz, while the other two were intent on pursuing rock.

“It was just time to put The Doors to bed,” Manzarek explained to Melody Maker later that year. “Some things can go on for a long time and others can’t. And The Doors without Morrison weren’t The Doors, were they?”

Krieger and Densmore stayed on in the UK and formed the Butts Band with singer Jess Roden and others. The group lasted through a major line-up change, relocation to Los Angeles and two so-so studio albums. It was, said Krieger, “our first lesson in trying to escape the shadow of the past”.

Meanwhile, Manzarek released a couple of ill-judged solo albums, briefly rehearsed with Iggy Pop, and in 1977 started his own band, Nite City. Nobody bought those records either. The shadow of the past, it seemed, was longer than any of them imagined.

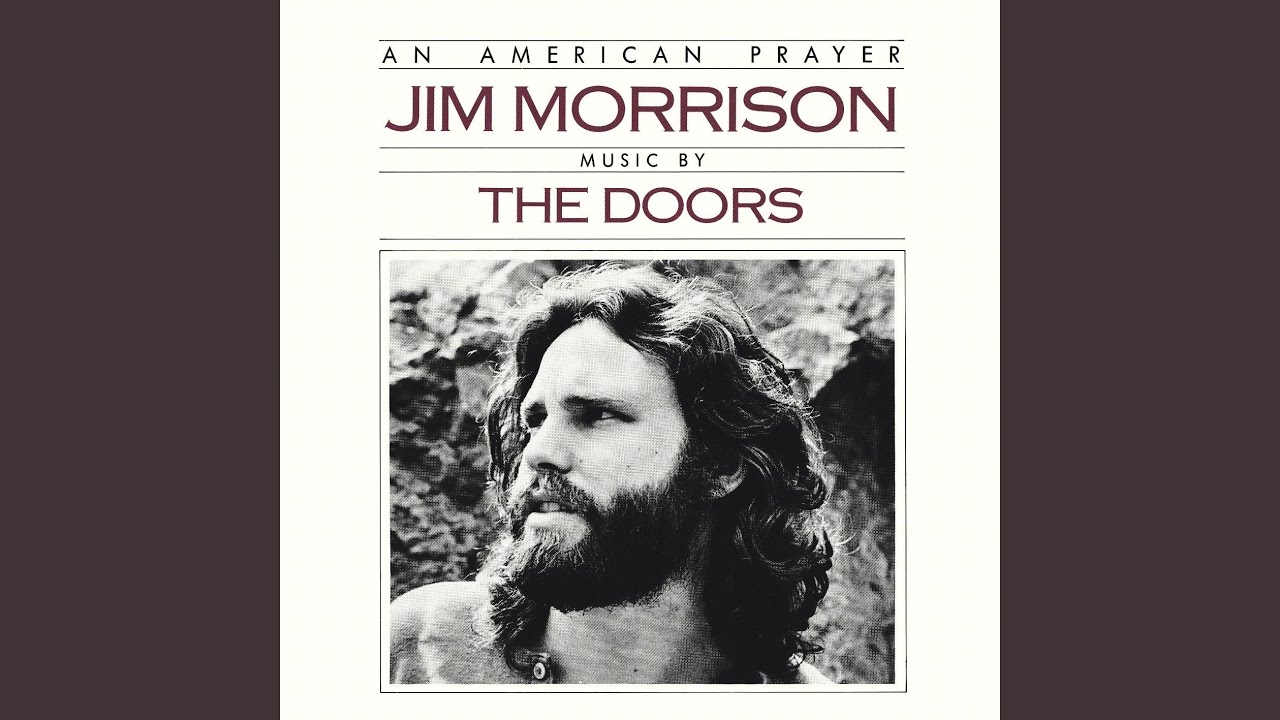

Sometime in 1977, Krieger was sorting through some old boxes when he happened upon a present that Morrison had given him prior to leaving for Paris. Morrison had self-published a book of poetry, bound in red leather and gold-stamped with the title An American Prayer. Leafing through the slim collection, the guitarist began thinking.

Morrison had gone into the studio to record some poetry in February 1969. The idea, hatched between him and Jac Holzman, was to release a spoken-word album for Elektra. The singer returned to Village Recorders in LA on December 8, 1970 – his 27th birthday. Producer John Haeny picked up Morrison on the way, stopping off at a liquor store to buy him a bottle of Old Bushmills Irish whiskey as a gift. There was methodology in his tactic. As Haeny later explained: “[Ex-Doors producer] Paul Rothchild told me that Irish whiskey was the key that unlocked the door to the room where Jim kept the crazed Irish poet.”

In the early summer of 1971, at Morrison’s request Haeny had intended to travel to Paris to record the album in earnest. But it wasn’t to be. The producer ended up sitting on the session tapes for the duration, until Krieger called several years later. Haeny duly invited the three surviving Doors up to his house in Laurel Canyon to have a listen to the recordings.

“When Jim’s voice came out of the speakers, I instantly heard lifts and falls,” Krieger recalled in Set The Night On Fire. “Rhythms and hints of melodies. Jim had a naturally musical way of speaking, and it immediately sparked ideas in my head for guitar licks and chord structures.”

With Haeny overseeing the project, Krieger, Manzarek and Densmore once again set about the task of putting Morrison’s words to music.

Blues seemed the obvious starting point as a textural backdrop, perfectly illustrated on the sultry, bruised Angels And Sailors. But The Doors opted to mix it up, guided by the varying cadences and tones in Morrison’s speech. Curses, Invocations pivots around a discreet jazz riff; American Night is all clangy dissonance; Ghost Song dives into fusionist funk, with Manzarek vamping away while guest Bob Glaub punctuates things with snapping bass.

Other elements are drawn from audio collage. There’s dialogue from Morrison’s experimental film HWY: An American Pastoral, bits of jam sessions, excerpts from Riders On The Storm and such. An unruly live version of Roadhouse Blues is spliced from two Doors gigs in New York and Detroit from 1970. A Feast Of Friends is set to a new arrangement of classical piece Adagio In G Minor, which the band initially recorded during sessions for The Soft Parade. “Jim had always loved the recording,” justified Krieger, “so we thought it would be fitting to revive the song for him.”

Thematically, An American Prayer was both self-glorifying and conceptual. The Doors split the poems into five loose sections, covering Morrison’s formative childhood, high school years, poetic ambitions, Doors fame and, as Manzarek later put it, “a final summation, in a way, of the man’s entire life and philosophy”.

Released in November 1978, the album did much to massage the myth. Dawn’s Highway featured the oftrepeated tale of how the Morrison family – with four-year-old Jim in the back – came across a truckload of Native Americans scattered on a desert highway, bleeding to death after an accident. Looking back, he believes that ‘the souls of the ghosts of those dead Indians, maybe one or two of ’em, were just running around freaking out/And just leaped into my soul.’ Here was Morrison portrayed as rebel poet and shaman, rock’s broody leather Dionysus, mojo risin’ from the grave.

Never mind the mixed reviews, An American Prayer went platinum, becoming the biggest-selling spoken-word album in history at the time. Its success set into motion a Morrison revival that quickly morphed into cultural fixation. Within six months, Francis Ford Coppola was using The Doors’ The End to presage the dread and horror of Apocalypse Now, Morrison’s soul-purging nightmare writ large over American involvement in Vietnam.

In 1980, No One Here Gets Out Alive, by Jerry Hopkins and Danny Sugerman, became the first Morrison biography. Criticised for Sugerman’s implication that the singer may have faked his own death, its sensationalism fed directly into the growing legend.

Elektra sensed an opportunity too. A reissue of The Doors’ debut album was a hit all over again. A hurriedly assembled ‘greatest hits’ collection went multi-platinum. By September 1981, Rolling Stone had Morrison splashed on its cover, 10 years after his death, under the editorial: “He’s hot, he’s sexy and he’s dead!” It turned out that Morrison had already called it in the words of An American Prayer: “We live, we die and death not ends it.”

Freelance writer for Classic Rock since 2008, and sister title Prog since its inception in 2009. Regular contributor to Uncut magazine for over 20 years. Other clients include Word magazine, Record Collector, The Guardian, Sunday Times, The Telegraph and When Saturday Comes. Alongside Marc Riley, co-presenter of long-running A-Z Of David Bowie podcast. Also appears twice a week on Riley’s BBC6 radio show, rifling through old copies of the NME and Melody Maker in the Parallel Universe slot. Designed Aston Villa’s kit during a previous life as a sportswear designer. Geezer Butler told him he loved the all-black away strip.