Psych-rock legend Grace Slick is in the middle of telling us a story. It's Chicago Auditorium, 1973. Jefferson Airplane are tuning up. Slick, better known as their singer, exchanges banter with her home-town crowd. “I’m getting ready to sing. Some guy in the audience shouts: ‘Hey Gracie! Take off your chastity belt!’ I look directly at him and say: ‘Hey, I don’t even wear underpants.’ I pull my skirt up for a beaver shot, and the audience explodes with laughter. I can hear the guys in the band behind me muttering: ‘Oh, Jesus.’”

The story, like most of the tales that surround the legendary pin-up girl for the Summer of Love, isn’t apocryphal. Slick used it to open her autobiography Somebody To Love? A Rock And Roll Memoir, one of the funniest accounts of the whole West Coast psychedelic extravaganza ever written. “I shaved my legs, but I talked like a truck driver,” she said. She was the bohemian who defined a generation in the USA. And she had, as Patti Smith has noted, dark violet eyes like Elizabeth Taylor.

Four decades later, the poster girl for the Monterey and Woodstock kids is as candid as ever. Unrepentant for the most part, this is a woman who survived years of drug and alcohol abuse, has been arrested on numerous occasions (mostly for drunk driving, but once for pointing an unloaded gun at a police officer answering a domestic disturbance call), and has done her best to uphold her end for the baby-booming permissive society’s war against The Man.

She once turned up at the White House for an informal party hosted by Tricia Nixon, hippie-loving daughter of then president Richard Nixon (Grace and Tricia were alumnae of the prestigious Finch College finishing school in New York). Grace had a gift in her bag – she was carrying a stash of powdered LSD, which she intended to slip into Tricky Dicky’s vodka martini. Unfortunately, she was turned away at the gates by security once they realised she’d brought along Abbie Hoffman, who was co-founder of the anarchic Yippies, as well as being high on the CIA’s Most Wanted list.

Luckily for the authorities, Grace Slick has left the music business, although she appeared at a post-9/11 benefit for NYC firemen – wearing a burqa – and wrote a song for victims of the New Orleans oil spill. Today she leads a relatively quiet life in Malibu, a paradise for well-heeled rockers of a certain age. “There’s a fuzz on the ocean today so I can’t see my neighbours,” she says. “Most of them are famous, but my friends aren’t. My best friends are a former air stewardess and a caterer. The only famous person I know is David Crosby. We’ve rescued each other numerous times for drug-related problems but we’ve been sober for a long time now.”

Grace Slick and Jefferson Airplane: The beginning

Grace Slick had been earmarked to join Jefferson Airplane in 1966 as the replacement for the band’s original female singer, Signe Anderson, who had just given birth to daughter Lilith. The former model’s foghorn vocals, enormous charisma and drop-dead beauty aside, Slick gave the Airplane their biggest hit songs. Somebody To Love, written by her brother-in-law Darby (she was married to drummer Jerry Slick) and sung by Grace in her previous band the Great! Society, was already a Bay Area smash. Adopted by the Airplane, it became the West Coast anthem. Grace’s own White Rabbit, a strident combination of bastardised Spanish bolero rhythm and psychedelic lyrics paraphrased from Lewis Carroll’s book Alice In Wonderland, confirmed her position as the Acid Queen of Haight Ashbury.

“I wrote that after taking LSD and listening to Miles Davis’s Sketches Of Spain album for 24 hours. It was going to be called Feed Your Head. [Airplane guitarist/singer] Paul Kantner said: ‘Sing that Arabic jamming thing you do.’”

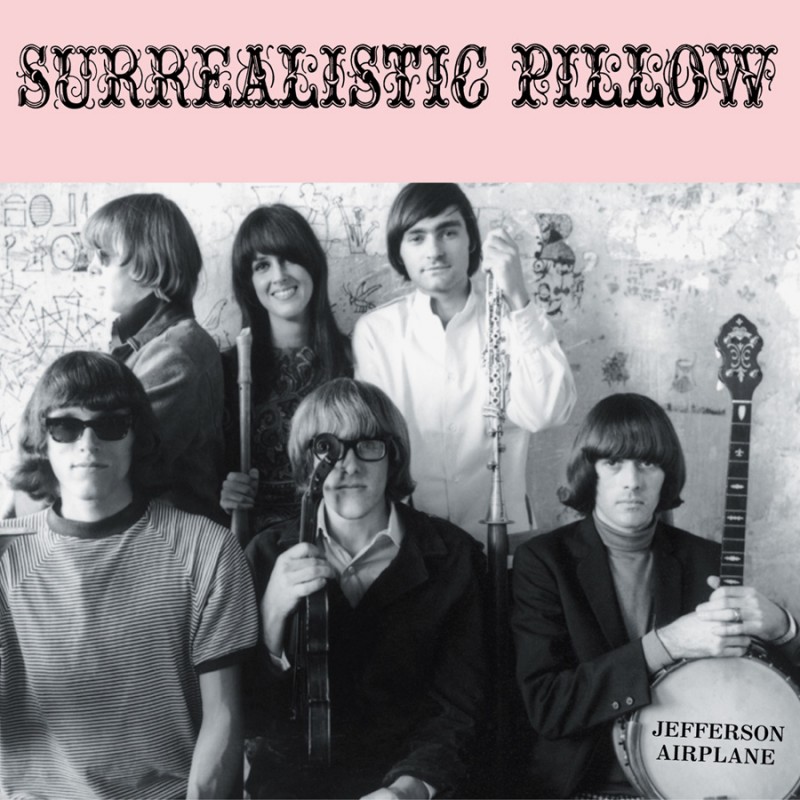

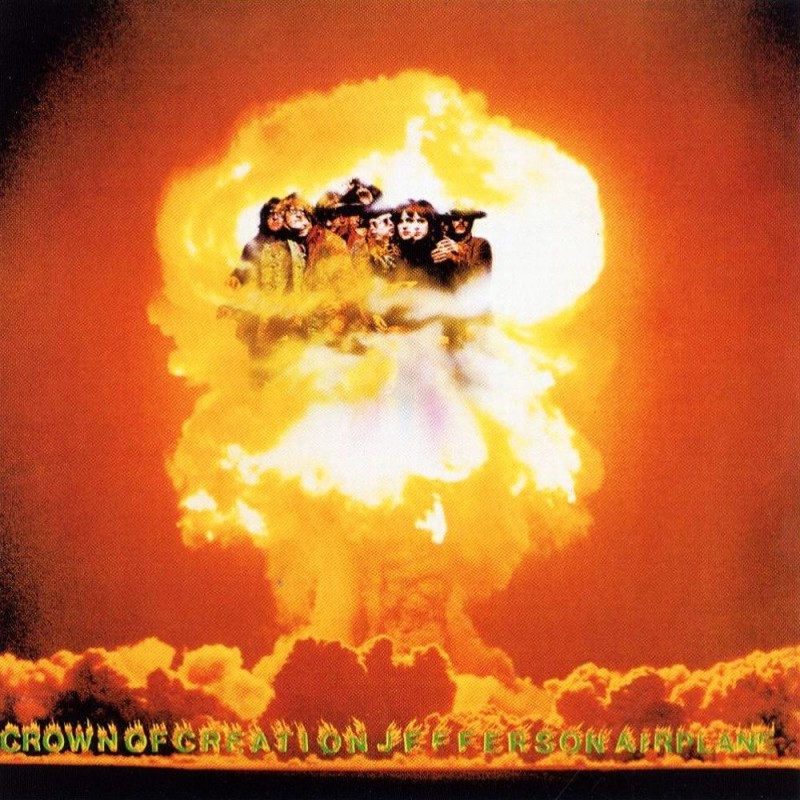

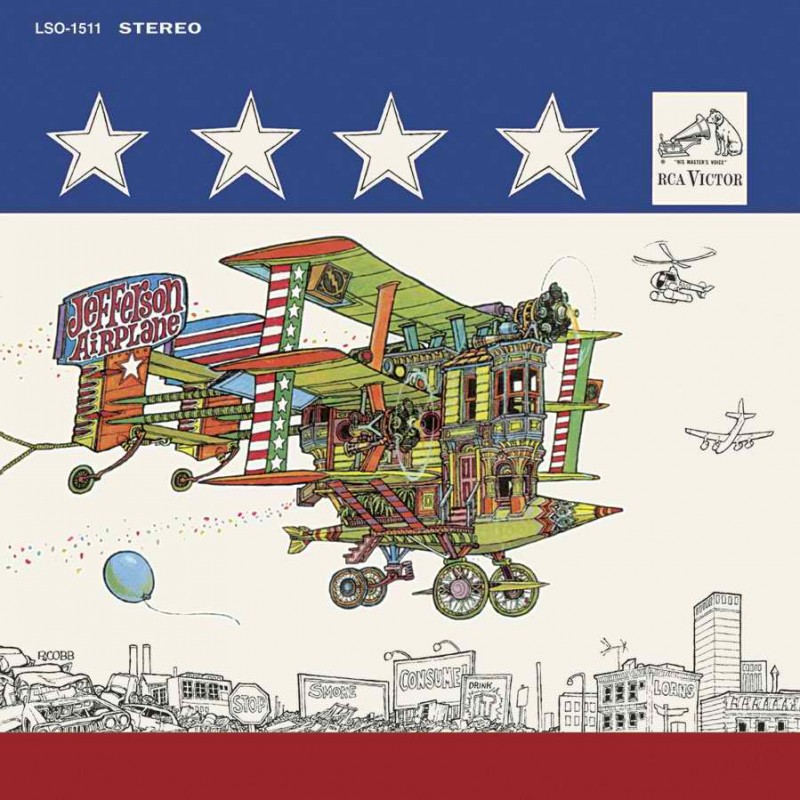

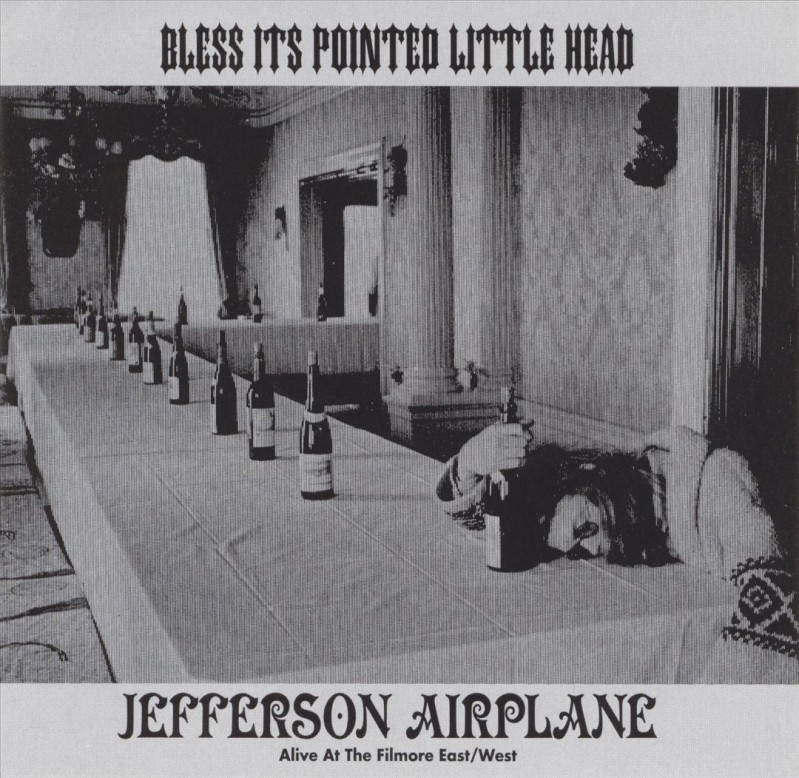

Marty Balin was ambivalent towards his new fellow singer – he was firmly in the ‘keep Anderson’ camp. Despite Jefferson Airplane’s string of classic albums – Surrealistic Pillow, After Bathing At Baxter’s, Crown Of Creation, the live Bless Its Pointed Little Head and the ‘up against the wall, motherfuckers’ epic Volunteers – the pair prowled around each other, on stage and off.

“Marty was never very communicative, which is odd when you’re singing duets. Maybe he was jealous of me ‘cos I was so fabulous,” she laughs. “He’s the only one [of the band] I never speak to anymore. Jack Casady, Jorma Kaukonen, Paul Kantner – anyone who’s alive is fine. Not Marty. His wife calls me once a year – when she’s drunk.”

Slick made her live debut with the Airplane at the Fillmore auditorium in San Francisco on October 16, the day after Signe’s farewell speech to her fans at the same venue: “I want you all to wear smiles and daisies and box balloons. I love you all. Thank you and goodbye.”

Marty Balin gave Anderson flowers. The band’s manager and promoter, Bill Graham, led a standing ovation. Many in the audience wept.

Rather than make an anonymous backstage entrance, Slick toughed it out and queued up with the San Franciscan faithful. They marvelled at her attire – she was modelling at the time – a chic striped silk vest and a hip-hugging mod herringbone skirt. “Clothes were fun and I had some good stuff. I wore the same clothes on the street as on the stage. I got a lot from thrift shops in the Haight.”

Undoubtedly stylish, Slick provided a fashion template, especially when she started sporting a Girl Scout uniform. “Most of the bands looked pretty sharp, apart from the Grateful Dead who walked around in jeans and T-shirts,” she says. “The Charlatans were the best. They wore Western riverboat gambler suits. The Brits were different. I was invited with Kantner to meet Mick Jagger at his Chelsea home to discuss the Altamont concert. I was scared because I thought we were going to walk into an orgy. I’m not against orgies, but I’m not a good multi-tasker. I like one man, one child, one house and one car. Everything else is too confusing. There was no orgy. Jagger’s house was like my parents’. He had oriental rugs, Louis XIV furniture. He was in a three-piece suit. He gave us tea; didn’t offer liquor, didn’t proffer drugs. This was disappointing. We had a formal chat and Altamont was arranged – we would support the Rolling Stones.”

The now infamous Altamont concert was a disaster. Slick knew it was starting to get ugly when the Hells Angels invaded the stage during the Airplane’s set: “Marty Balin told ’em to fuck off and they backed down a bit.”

Not much, though. According to Balin, he was rushed by several Angels with pool cues. “Boom! I got knocked out and woke up with boot tattoos all over my body. The only person who said anything to me was Jorma Kaukonen: ‘You’re a crazy motherfucker.’ And here’s a guy who travels with machineguns, knives, macho bullshit lead guitarist crap.”

Back to Grace: “We started watching the Stones but decided to leave in a hurry. We were in our helicopter, looking down, and Kantner says: ‘I think they’re beating a man to death down there.’”

Paul Kantner would become Grace’s third Airplane sleeping partner, and father of her daughter China. Grace had joined the band initially “because I wanted to have an affair with bassist Jack Casady. I love bass players, and he’s the best.”

After Jack, she began a relationship with drummer Spencer Dryden. Guitarist Jorma Kaukonen was more like a brother. He once pulled her from the smouldering wreckage of a sports car after she’d crashed it into the Golden Gate Bridge. Marty was less chivalrous. “Did I sleep with her? I wouldn’t even let her give me head.”

Grace Slick: "The Airplane let me sing. God bless America for that"

In a male-dominated environment, Grace stood out. She was the poster girl for the Monterey and Woodstock era but never saw herself as an icon. “Women have always been singers. Female Supreme Court judges, that’s impressive. I just thought I was a singer – not Bach or Mozart or Handel. ‘Course, if we were all singers we’d be in terrible shape. Where would the farmers be? The Airplane let me sing. God bless America for that.”

Sexism wasn’t on her agenda – she had just as much fun as the guys. “I pretty much nailed anybody that was handy,” she once claimed. “My only regret is that I didn’t get Jimi Hendrix or Peter O’Toole.”

Jim Morrison was another matter, though. During the legendary Doors/Airplane European tour of 1968, she ended up in Morrison’s bedroom at the Belgravia Hotel, where they romped around and covered each other with strawberries and other courtesy hotel fruit. “Jim was a well-built boy,” Grace remembered. “Larger than average.” But it was just the once, she sighs. “When I left I said: ‘Call me if you want.’ And he never did. So apparently I’m a terrible lay.”

Grace got her own back. Before the concert in Amsterdam, the Airplane purchased a slab of Lebanese Gold hashish, which they offered to Morrison to nibble. Greedily, he ate a huge chunk. Ray Manzarek remembers him stumbling on stage during the Airplane’s set. “Jim started singing with Grace and hugging her. Then he danced off the stage, went back into the dressing room and passed out.”

Slick chuckles. “I liked Jim. Most women did. He was gorgeous, but he was so screwy – half the time you couldn’t talk to him. He used himself as a human guinea pig, see how far you can push the human brain. I remember coming back from an Airplane gig in 1967 and going to the Tropicana Motel with Kantner, and Morrison was in the hallway, goofy on acid, stark naked and barking like a dog. Paul just stepped over him and went into his room.”

Befitting the times, the Airplane took prodigious amounts of drugs of all sorts. “Absolutely,” Slick says. “Personally I never freaked out on acid. I didn’t think it could affect you unless you had psychological problems to begin with, and I didn’t.”

She can recall most of her drug episodes. “When I want my drugs, I want them now. Alcohol was a downfall because it was easier to get. My favourite drug was Quaaludes [depressants] but you had to beg to get those. Sometimes they gave you Valium, but it took days to get off those. They took Quaaludes off the market. Stupid. They’re great if you’re a speed freak or an alcohol and coke user. Everybody loved ’em. I did because they didn’t make me angry like alcohol does. I didn’t drive funny and get arrested. I felt invincible and good but they didn’t turn me into a complete jerk. I’ve got a strong constitution, apparently. For example, it takes a lot of hospital morphine to make me pass out. Not me, doc. Give me Quaaludes and I’m feelin’ fine.”

Evidently a force of nature, Slick regularly performed live with the Airplane while under the influence. “Not sure I’d recommend that to everyone,” she says, “because taking drugs and working is gnarly. The band played in Fargo, North Dakota, once and our tour manager had a plastic box full of drugs in various compartments – powders and pills. We all took a nail full of what we thought was cocaine but turned out to be acid. After 15 minutes I was so tripped out I stopped singing and playing piano and listened to Jack Casady’s bass.

“The way I saw it was this: I’m young, healthy, I’m not miserable, I can take all the drugs I want, screw whoever I want, ‘cos they don’t have Aids yet, and I’m being paid to travel all over the world and dress any way I want. Come on! We were rock’n’rollers, not bankers.”

Those who saw Grace Slick in her pomp still put her on a pedestal. Writer and scenester Eve Babitz – the Dorothy Parker of the West Coast scene – recalls: “Grace had a Napoleon complex because she’s kind of short, which pissed her off. But she was certainly gorgeous and she expanded to fill a stage. You couldn’t escape her. She got on the cover of Life magazine wearing her Girl Scout uniform, which seemed amazing at the time. She could still get into it because, like everyone else on the West Coast rock scene in 1966, she was snorting acid, doing speed and uppers, so she didn’t eat. That’s how Jim Morrison stayed so skinny. People only got fat when they discovered cocaine.

“Grace always thought she was ugly,” says Babitz. “I remember she wore a white Native American Indian outfit at Woodstock, and she hated the photos so much she tried to stop the Airplane footage being used in the film.”

In fact, the Airplane’s Woodstock performance was almost up there with Hendrix’s version of The Star Spangled Banner. They came on at daybreak on the Sunday, August 17, just after The Who. Slick looked at the huge crowd in awe before telling them: “You’ve heard the heavy groups, now you will see morning maniac music. Believe me. Yeah, it’s a new dawn.”

As epic as such moments were, she prefers her more mundane account. “I was wearing feathers and shells and this white dress. Took ages to get it looking right. So while the rest of the band were playing pool and getting fucked up in the hotel, I was trying on my accessories. I wanted to look good. I thought I was hot. But then later someone says: ‘Damn. Why didn’t she look into a mirror before she went on?’”

Why worry? The Airplane had released five gold albums in three years. Grace Slick was a superstar. West Coast archivist Alec Palao wrote: “More than anyone else, she was the most original and unique talent to emerge from the whole San Francisco 1960s milieu.”

For Grace, “it was all a hoot. The first LP I did with the Airplane, Surrealistic Pillow, was easy. We went into RCA’s Hollywood studios, where they’d recorded Frank Sinatra, Elvis Presley and the Rolling Stones. It had a wooden floor. We put up our four huge Altec speakers and rocked. We had complete artistic control. RCA never told us what to do because we put arses on seats, and the producer, Rick Jarrard, was always drunk, so he didn’t interfere. We ended up producing with the engineer, Dave Hassinger, and tripped through it all with Jerry Garcia as our ‘spiritual adviser’. Ha!” In the late summer of 1968, the Airplane toured Europe, amazing audiences with their brutal PA and psychedelic light show. On August Bank Holiday, they were paid £1,000 to headline the first Isle of Wight Festival. “I am frozen to the bone!” Grace shouted.

The festival date was followed a few days later by a free concert for a few hundred curious folk in the dilapidated bandstand on Parliament Hill Fields in North London. Sponsored by Camden Council (and publicised only the day before by John Peel on his radio show), it wasn’t exactly a triumph. The weather was so bad that Slick’s first words were: “What’s wrong with you people? It’s raining. Go home.”

After Europe, the Airplane paid $73,000 for an outrageously palatial mansion at 24000 Fulton Street, San Francisco. They painted their new HQ black, moved in their personal coke dealer and installed a medieval-style torture rack in the basement, which was first tried out on David Crosby. Slick bought a shotgun and amused herself by firing it from her window over the trees of Golden Gate Park.

In 1969, the Airplane were the wealthiest band on the West Coast. But that didn’t stop them making Volunteers, a radical, revolutionary, call-to-arms album.

“We had the most fun making Volunteers,” Slick recalls. “Jorma used to drive into the studio on his motorcycle. And we spent a lot of time sucking on a gigantic canister of nitrous oxide in the corner of the room, laughing like idiots.”

And the revolution? “That didn’t happen. I thought you could change people with media blitzing, books and knowledge, but you can’t. The only person I can change is me.”

Indeed, as their music became more bombastic, the Airplane’s record sales started to slide. Volunteers flopped as a single. So did the follow-up, Mexico, a savage repudiation of Richard Nixon’s Operation Intercept, which effectively closed the US/Mexico border to stop marijuana smuggling.

Within the year, rock’s relationship with hardcore drug abuse saw off Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Morrison, all aged just 27. Even Grace was shocked. “Janis had been a friend for a short period when we were younger. Before things got ugly. It’s the luck of the draw. I saw how heroin affected people. My own alcoholism was a slow decline. It’s stunning I’m still alive. I’m glad I didn’t do heroin. It killed all of them. Hendrix died because heroin makes you puke. It is also very illegal.”

The 70s were increasingly a blur for Slick and the Airplane. Drummer Spencer Dryden quit in 1970, still shattered by Altamont. Marty Balin made a more protracted exit before deciding he’d had enough of “playing that messed-up cocaine music”. Kaukonen and Casady stuck around but poured their energies into their emerging other band, Hot Tuna, effectively leaving the Airplane in Kantner and Slick’s care. Slick persevered with Kantner’s new venture, Jefferson Starship, but she grimaces at the memories. “That was a sell-out band. The Airplane was a smorgasbord, but the Starship I hated. Our big hit single, We Built This City, was awful. What are you talking about? What city? LA was built on oranges, film and oil. San Francisco was built on the gold rush. The Romans built London. It sounded like we were bragging, even though Bernie Taupin, an Englishman, wrote the lyric. I could sing it – and the others – because I can fake enthusiasm. You have to act to get on stage. I felt like I’d throw up on the front row but I smiled and did it anyway. The show must go on.”

While Kantner was obsessed with creating what Grace calls “let’s all go outer space, science-fiction shit”, she fell back on sarcasm, fuelled by boozy bravado. “I had no filter. When I was drunk, if someone was an arsehole I’d say so. I’ve got very little gate between what I think and what I say. It isn’t a syndrome, I’ve just got a lack of discretion. I became a jail-arrested, rock’n’roll, foul-mouth bad girl.”

Grace Slick and Jefferson Airplane: The beginning of the end

In 1978, Slick’s antics, her no-show behaviour and total lack of self-control came to a head at a show in Hamburg. She bought a child’s Heidi outfit, then got so smashed she decided that dressing like a Nazi, goose-stepping and giving the ‘heil Hitler’ salute – while asking: “Who won the fucking war? It was all your fucking fault” – was a good idea. What might have been a hoot in California didn’t go down well in Germany. The audience rioted, stormed the stage and set fire to the band’s equipment, before chucking it into the river. Quite an evening. Paul Kantner sacked her on the spot, which meant she missed playing the Knebworth Festival a few days later.

Eventually, Slick faced her known demons, and she became the first high-profile rock star to admit to attending AA.

“It wasn’t easy. Being sober is weird. People magazine broke my anonymity about AA but it wasn’t a surprise. My behaviour made that obvious. Everybody knew I was a big drunk. Plus, booze and cocaine is an ugly combination. I loved it. I lived on it, because the two things even each other out. Then you do more. I could afford it. Coke was so cheap and we were rock’n’rollers. Who cares? I only stopped when you couldn’t get the uncut stuff from German pharmaceutical chemists. I was a snob.”

Her last husband, former Airplane lighting man Skip Johnson, told her she was becoming too Jekyll and Hyde for comfort. “When I was sober I was calm. Otherwise, a pain in the ass. I was having a great time and everyone else was like, ‘Oh, Jesus. Shut her up.’ If I saw anyone in a uniform, it was over for me. I went to jail a lot for drunk mouth – verbal assault.”

- The story of Moby Grape: chaos and courtrooms, acid and white witches

- The Story Behind The Song: White Rabbit by Jefferson Airplane

- Hippie Archeology: the lost vinyl of Olompali

On the road to sobriety, Slick decided to quit the stage. “I don’t like seeing people my age leaping around, singing about their feelings when they were 23,” she says. “If you’re comfortable with it, go ahead. I’m easily embarrassed for people. ‘Oh my God, honey, get off the stage. Become a producer or something.’”

Kantner still does it. “Well, if you’ve squandered your money and you have to play, be my guests. I haven’t, so I don’t. My dad, who was a merchant banker, always told me: put one third into savings, one third for bills and screw around with the rest.”

These days, Grace rises at 4am every day and starts painting. She paints what she knows: white rabbits, portraits of dead rock stars, wine labels, marijuana plants, ice-cream- guzzling kids as metaphors for the obesity epidemic.

“They used to sell well. Me and Ronnie Wood have the same agent and we sell to the class of people who don’t really need art or drugs, all the stuff I like. Corporate people. I don’t live off my art though. If I did, I’d be starving. Royalty cheques are great. I always knew once the Airplane became famous that it would be around until I drop dead.”

“Anyway,” she laughs, “I deserve it. I wrote a few good songs. And I’ve never bounced a cheque in my life.”