In January 1971, 20-year-old Neil Andrew Megson changed his name by deed poll. “It was one of the only times we really upset my mum,” he recalls. “We were hitching down to London and stopped off at my parents’ place: ‘Erm, there’s something we need to tell you. We’re not Neil Megson anymore, we’re now Genesis P-Orridge.’ And she just started crying. She saw it as a rejection. And it was, but not of her. It was a rejection of the traditional way people labelled and limited their culture.”

This rejection of accepted societal norms has been a central theme in the work of Genesis P-Orridge. It’s there in the industrial anti-rock of Throbbing Gristle, the band he founded in 1975, and in his subsequent tenure as leader of post-punk deviants, Psychic TV. Both groups thrived on chaos and confrontation, their music a constantly evolving mix of brutal noise, avant-pop and strange electronica. Their lyrical preoccupations too – illicit sex, murder, ritual, fascism, the occult – were designed to shock, to provoke extreme reactions.

Above all, the idea that identity is fluid rather than fixed is reflected in Genesis P-Orridge himself. If prog is often defined as the impulse to break down barriers and taboos, to explore new opportunities, then he is its living embodiment. Along with second wife Jacqueline Breyer, the 90s saw him begin a series of “body modification” experiments that involved cross-dressing, breast implants and hormone replacement therapy in order to merge as one “pandrogynous” entity called Breyer P-Orridge. Another detail was the adoption of neutral gender pronouns (each of them now being addressed as ‘s/he’), which also explains why Orridge now refers to himself using the plural ‘we’ as opposed to the singular ‘I’.

Confused? For Genesis, it’s actually very simple: “There’s a phrase that sums it up: ‘Viva la Evolution’. I have a patch on the back of my denim jacket that Lady Jaye [aka Breyer] gave me, that just says: ‘Change’. It’s important for people to understand that they really can be anyone they want to be. Jaye used to say: ‘Why wake up in the morning and be who you were yesterday?’”

Lady Jaye died in 2007 from a heart attack, probably related to stomach cancer. Genesis has now documented h/er life, and the couple’s relationship, in a hefty new book. Genesis Breyer P-Orridge, gleaned from reams of personal archives, is a tome that combines over 350 photographs (some of which, be warned, are very intimate), essays, artwork, commentary and memorabilia.

It’s been an extraordinary life. Born in post-war Manchester, h/er musical tastes were initially inspired by h/er father, a Dunkirk veteran with a predilection for jazz. “In my early teens, he started taking me to gigs at the Free Trade Hall. We saw Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Buddy Rich, all kinds of amazing jazz musicians. A lot of it was based on improvisation, and that always made sense to me. It was like: ‘Why should it always be the same?’”

In the 60s, at Solihull School in the Midlands, Orridge discovered the writings of the Beats. H/er imagination was fired by Kerouac, Ginsberg and especially the random cut-up techniques of William Burroughs and Brion Gysin. Then came Dada, Surrealism and Andy Warhol. “These people’s lives were as fascinating as what they made, often even more so. It fitted in with how we felt, that it was more like a calling to be an artist of any type. It was like being a priest or doctor. It’s a mystical, spiritual activity. Life and art can never be separated.”

Then came a fascination with Captain Beefheart, Frank Zappa and Syd Barrett’s Pink Floyd. After dropping out of Hull University in 1969, s/he joined a semi-commune of freaks holed up in an old warehouse in the city. The university would call whenever they needed “anything strange” to accompany the many visiting bands who played there.

Orridge in particular remembers Pink Floyd breezing in to tour Ummagumma: “We were co-opted as an additional section of the light show. We were so excited at being asked that we ate these hash cookies on the way there, so everyone was stoned and tripping on top. We had these glass slides with liquid in, then also an epidiascope, onto which we put live maggots. So you had this amazing psychedelic light show, with six-foot long maggots crawling across. A lot of people forget I’m absolutely a child of the 60s. Throbbing Gristle was hard psychedelics.”

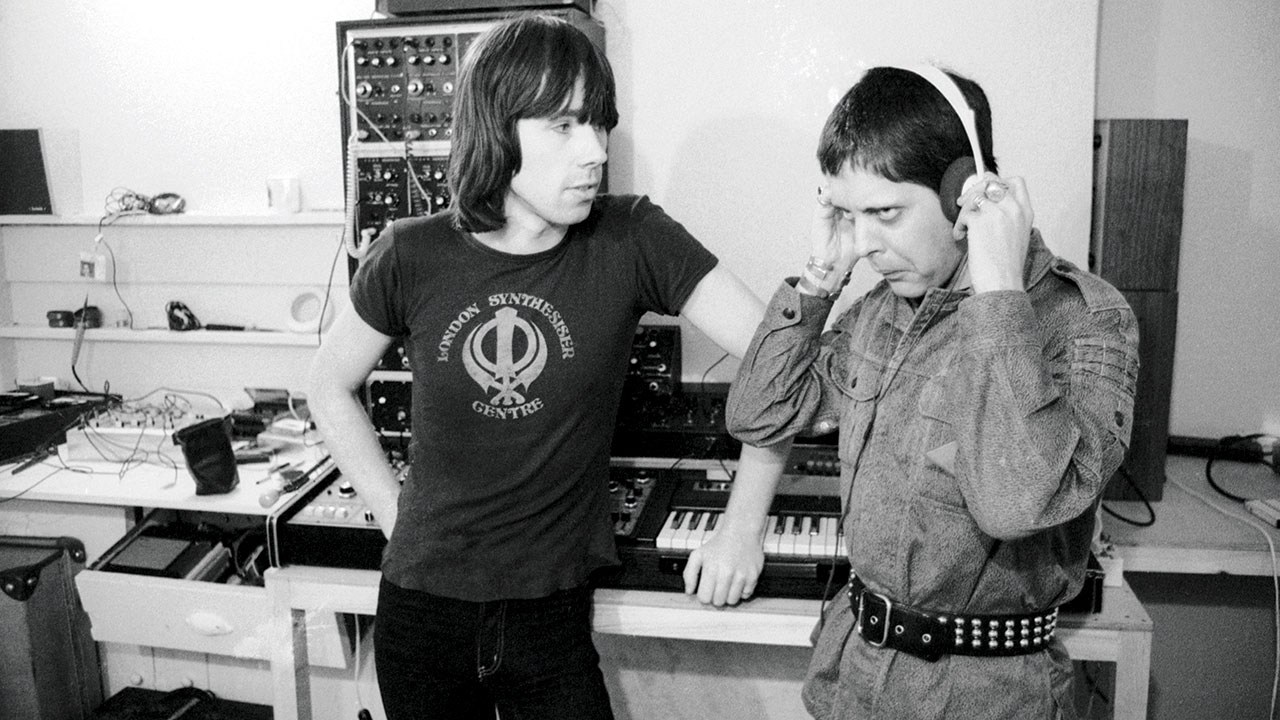

Later that year, inspired by the subversive prankery of Dada and the Situationists, Genesis co-founded the performance art ensemble COUM Transmissions. Alongside Peter ‘Sleazy’ Christopherson, Chris Carter and Christine Newby (aka Cosey Fanni Tutti), it was the same line-up that would eventually morph into Throbbing Gristle.

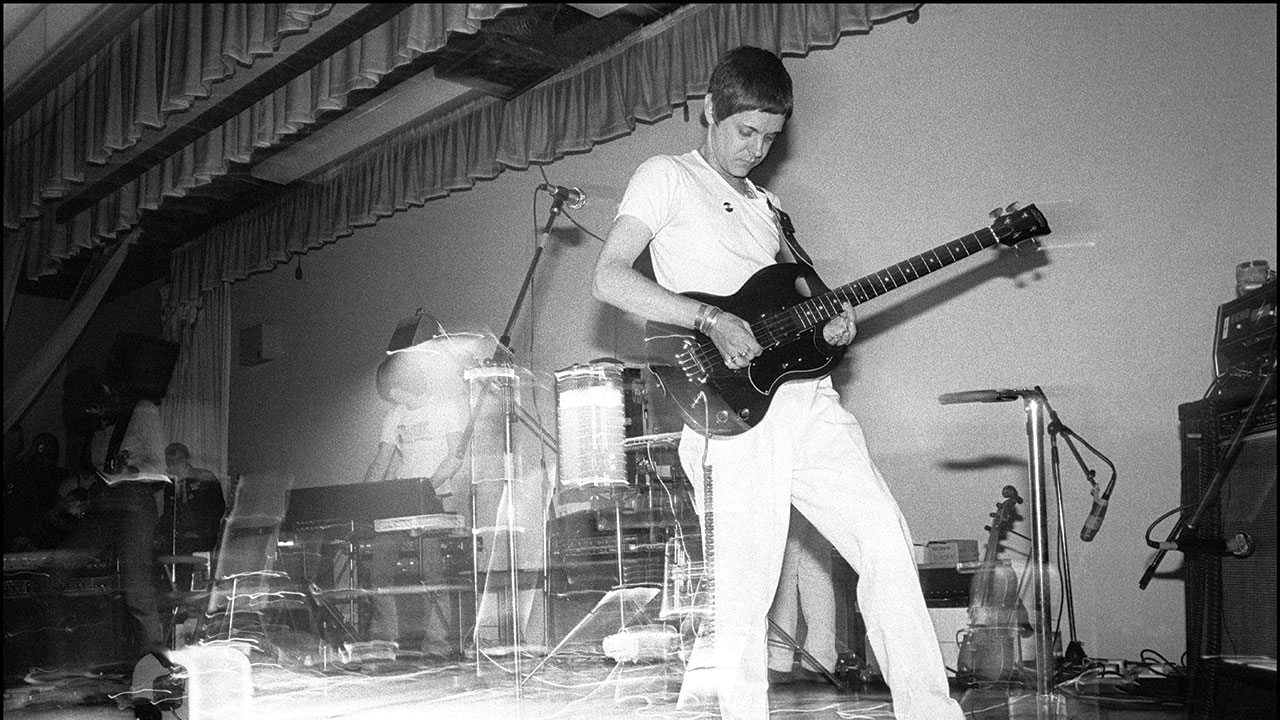

“At the beginning COUM was basically absurd theatre,” s/he explains. “People hated us. None of us could play and we just saw it as a big laugh. But as it got more serious, we started homing in on sexual taboos, transgression and who decides what’s okay in certain societies. We were seeing how far we could push the envelope of insanity. We had an amplified shop dummy that we’d bang with sticks to make rhythms. And one of the singers was on a surfboard on a bucket of water. Cosey was wandering around with a starting pistol, dressed as a schoolgirl. And Sleazy started collaging background tapes of sound.”

The transition to Throbbing Gristle coincided with their controversial show Prostitution, held at London’s ICA in 1976. The ‘happening’ included pornographic images, soiled nappies and an art deco clock stuffed with used tampons under the title: ‘That Time Of The Month’. There were questions asked in Parliament. Tory MP Nicholas Fairbairn called the group “wreckers of civilisation”, a quote gleefully appropriated by The Daily Mail.

The band’s early gigs weren’t received much better. “The first review said: ‘Even an ape with severed arms can play bass better than Genesis.’ And someone else wrote about my violin: ‘I’ve never seen such utter degradation of a beautiful instrument before.’ We felt encouraged!”

With Genesis on vocals, Throbbing Gristle were an uncompromising bunch. Debut LP Second Annual Report was a dense mass of industrial noise that included such queasy listening as Maggot Death and After Cease To Exist, the latter featuring the taped confession of a real-life killer.

For all the disturbing aspects of their work however, it wasn’t without black humour and self-mockery. 1978 single United was a favourite in the punk clubs, whereupon TG promptly sped it up as a remixed version that lasted just 16 seconds, while Death Threats, which appeared on that year’s DOA: The Third And Final Report, was a collage of abusive messages left on their answerphone.

By 1981 though, Orridge had become restless. “We were disillusioned and in a rut. TG was becoming commercially viable, but at the same time it was becoming stale. So being an idealist, we just thought it was time to stop.”

S/he had been dreaming up a new venture for some time. The sleeve for TG’s final single, Discipline, had included the description: ‘Marching Music for Psychick Youth.’ Plus some of their flyers had carried the words: ‘Psychick Youth Rally!’

“We were deliberately trying to sow the seeds of Psychic TV before the end of TG,” s/he admits. “We wanted to do something that was much more positive. It’s alright to be negative, like TG could be, and say everything sucks. But after a while you have to say: ‘Well what are you gonna do about it?’ So the idea was for Psychic TV to not just be a band, but also a network where the people who would normally just be fans are in more direct touch. And it grew into this alternative way of doing culture.”

Co-founded by Orridge and Alternative TV’s Alex Fergusson, with Peter Christopherson joining soon after, Psychic TV were far more free-ranging than TG. There was still a fair spread of juddering mechanical noise, but also a raw minimalism that allowed room for electronic pop, day-glo psychedelia and the liberal use of samples. By 1988 they were even at the forefront of the rave explosion with the single Tune In (Turn On The Acid House) and LP, Jack The Tab.

There were more diverse musical wanderings up until the late 90s, when Orridge decided to call it quits and concentrate on spoken-word projects. He revived Psychic TV for 2007’s Hell Is Invisible… Heaven Is Her/e and follow-up Mr Alien Brain vs. The Skinwalkers.

The band’s present compass points to all things prog. In the early 70s, Orridge devoured Amon Duul, Can, Jan Dukes de Grey and Hawkwind. “Prog had improvisation, which was interesting. And we’ve rediscovered it now with Psychic TV. We’re doing a series of 12-inch singles. The first one was Funkadelic’s Maggot Brain, but we added vocals. Then we did Mother Sky by Can, Silver Machine and Hurry On Sundown by Hawkwind.”

S/he finally got to play with Hawkwind’s Nik Turner in San Francisco in 1996. “Genesis is a very revolutionary character,” offers Turner. “Psychic TV and Throbbing Gristle were vehicles for his off-the-wall expressionism. Those who admire him love him for his weirdness and wildness and the fact he was a pioneer of electronic music in this country. He was an influential figure in terms of young musicians looking for new directions. And I think he enjoyed the fact that he presented himself as the anti-Christ for a while. Two members of my Inner City Unit band, Nazar Ali Khan and Steve Pond, were huge fans of Genesis P.”

Sometime collaborator Douglas Rushkoff, the US cyberspace theorist and graphic novelist, believes Orridge is responsible for “bringing the cut-up into the industrial and digital era. Burroughs and Gysin did cut-up manually, with physical newspapers and stuff. Gen did it with music, with genres, and then with industrial noises as a way of reclaiming power. Then he decided to do it with his body, and even with gender. S/he is a living cut-up, and continues to pay the physical, financial and psychological price for it.”

Orridge, now resident in New York, insists that it’s all been worth it: “When we do talks and lectures now, we’ve broken attendance records at universities. It seems to me that my job is to inspire people to take charge of how their life unfolds, to be the author of their own narrative and to throw it away when it gets boring. It’s not always easy and it can sometimes feel destructive, but for me it’s the only way to live.”

This feature originally appeared in Prog issue 40.