It is 10 o’clock on a rainy late summer morning when Jimmy Page arrives at The Gore Hotel to meet with Classic Rock. Situated in the London borough of Kensington, Page knows the hotel and the area well. He has a home nearby, and within a few minutes’ walk is the Royal Albert Hall, where Led Zeppelin were filmed in concert on January 9, 1970 – which was also Page’s 26th birthday.

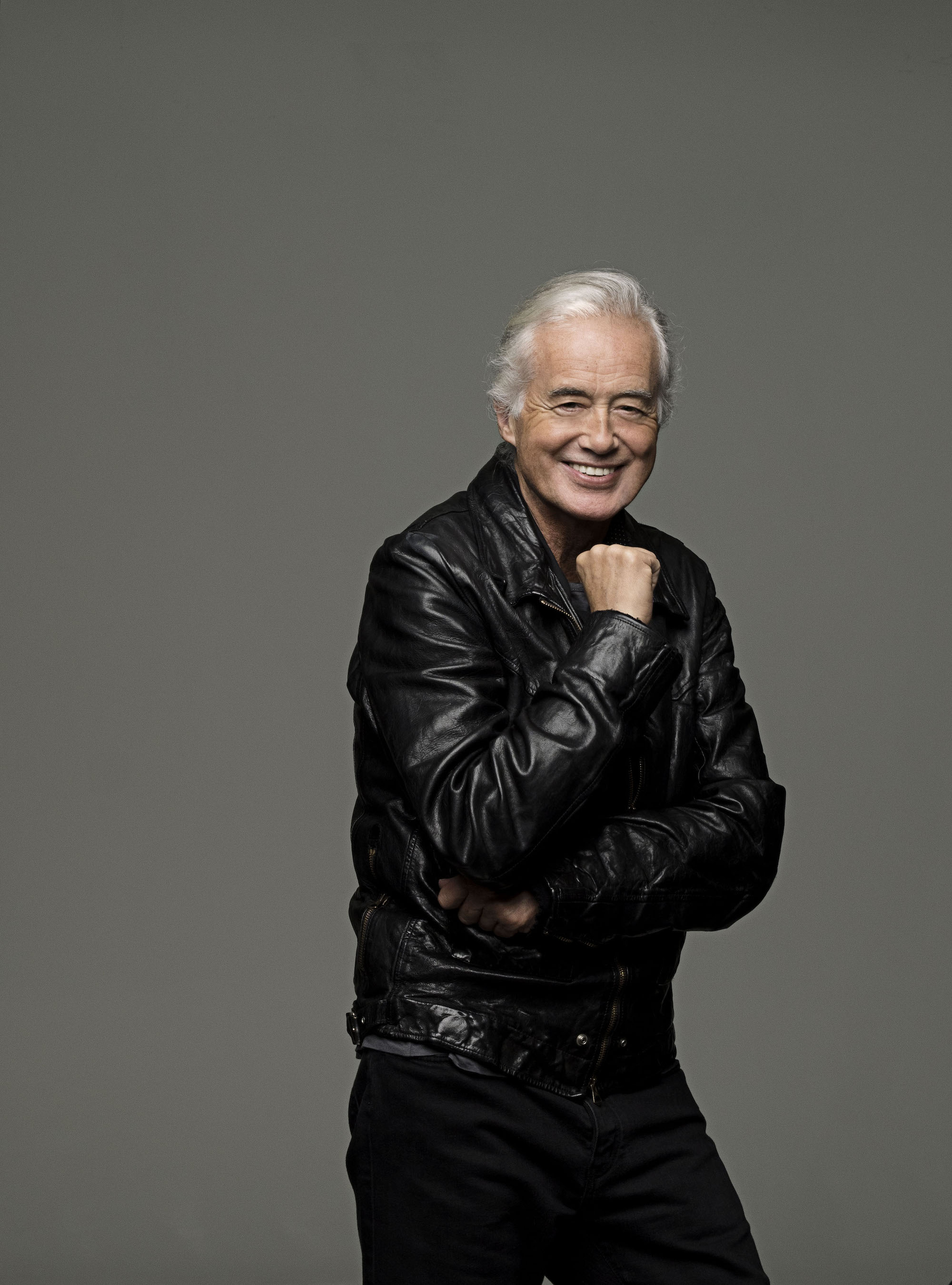

In the hotel’s Green Room, decorated with antique portraits of English nobility and lit by a vast chandelier, Page offers a warm handshake and settles on one of two facing sofas. Now 70, his shoulder-length hair its natural silver, the guitarist has aged better than most of his contemporaries. He is elegantly dressed in black shirt, trousers and boots, and drinking strong black coffee, with sweetener. “Too many of these and I’ll start speeding,” he says.

There’s a lot to talk about. In a conversation that runs to 80 minutes, Page will discuss everything from his life during those heady days of the early 70s as the leader, guitarist and primary creative force in one of the most successful rock groups of all time to his plans to release new music in 2015, music that he has been crafting for years. And he will also address the one question that will not go away: will Led Zeppelin ever perform together again?

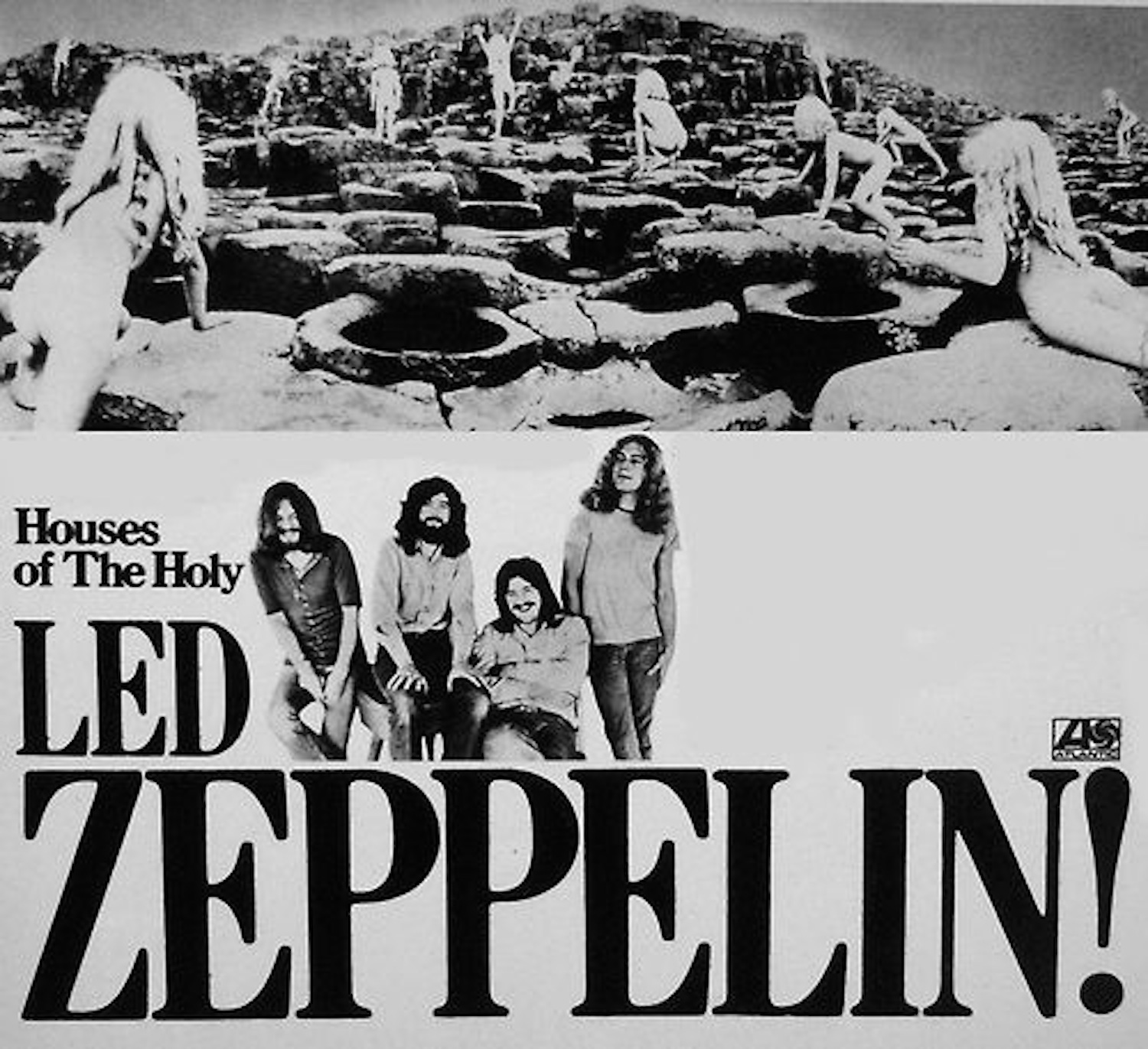

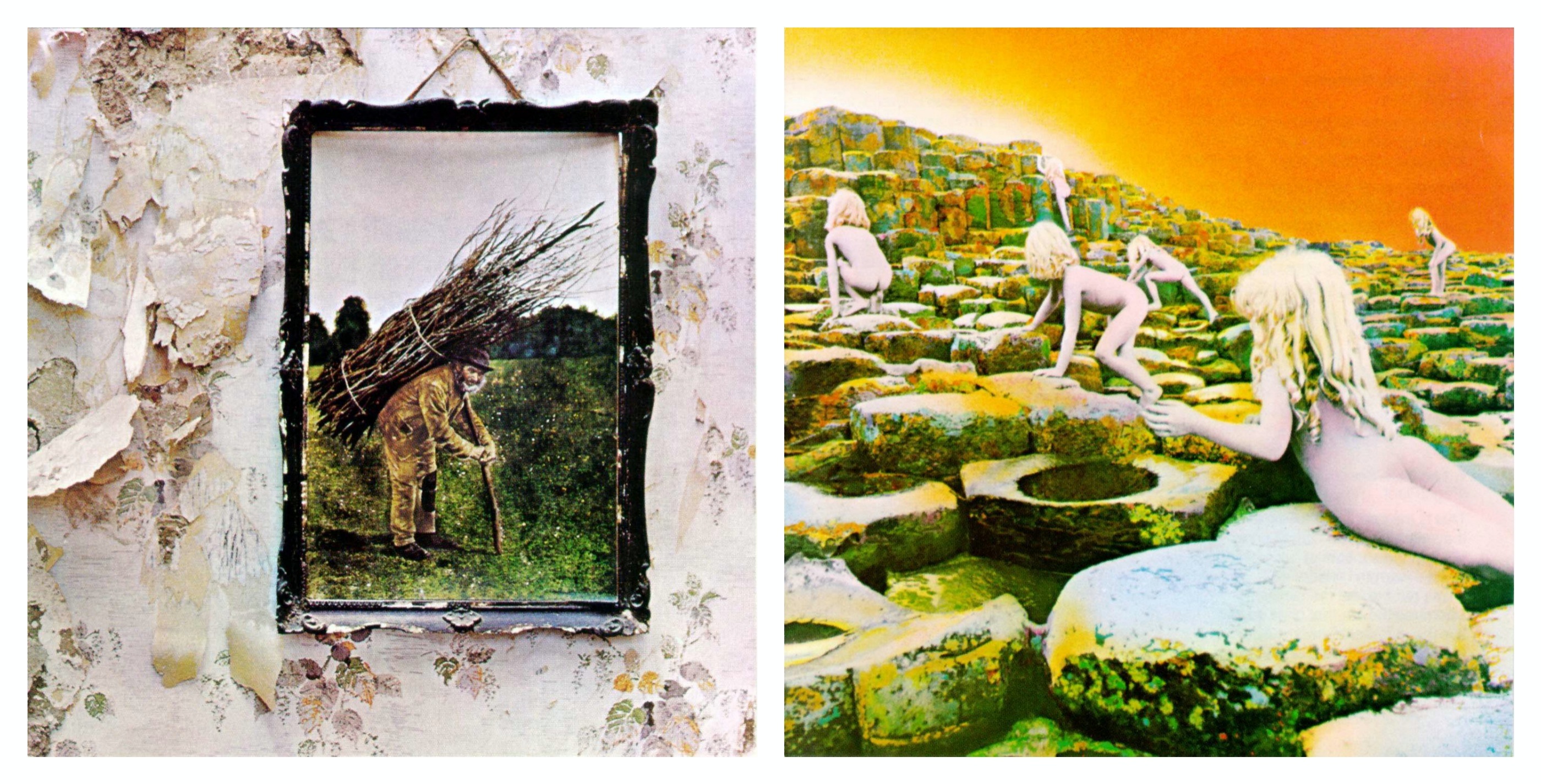

But there’s a more immediate matter at hand, which is the release of the two Led Zeppelin albums that form the second instalment in the high-profile reissue programme of the band’s entire catalogue: Led Zeppelin IV and Houses Of The Holy. Page smiles broadly when he recalls that untouchable period. “It was a wonderful time,” he says. “I can’t remember it all. But let’s see what I can remember…”

With Led Zep IV and Houses Of The Holy, there’s a broad consensus that this was the band at its absolute peak.

Well, I can’t say which album is the peak. The first album was a pretty fair introduction to what the band was. That album has so many ideas, and those ideas blossomed as time went on. But the fourth album, yeah, it was really serious, really good.

The received wisdom is that Led Zep IV was a reaction to the negativity that greeted the previous album. Is that how you remember it – that Led Zeppelin III was poorly received?

By the press – yeah. The press didn’t ‘get’ any of the albums. With the third album, they didn’t understand why we were doing acoustic music, except that it was all over the first album anyway. I wondered, where are these people coming from?

But the public got it.

We did great by the public, because once you’ve listened to Led Zeppelin, it’s got you. You get it: what’s going on, why it ticks, and the brilliant musicianship.

So with the fourth album, did you feel that you had to stick that press criticism back down their throats?

It just got to the point where you didn’t bother to pay any attention to them. Even after the third album, there were silly elements of the press in America that were saying, ‘Oh, the band’s a hype.’ And I was thinking, ‘Goodness gracious, this is just ridiculous now!’ But it didn’t matter.

For the making of the fourth album, in December 1970, you took the band to Headley Grange in Hampshire.

It was a manse, an old Victorian house, a wonderful place, and very imposing. I liked the idea of the whole band being in the same house, in residence, working. Fleetwood Mac had rehearsed there, although they didn’t record there. So I knew there wouldn’t be noise problems. It was in the countryside, so you weren’t going to have neighbours complaining. It seemed ideal.

What was the appeal of working there and being in residence? Was it the fact that you could make music at any time, day or night, whenever the inspiration came?

That’s the whole point. It’s a working environment. If it didn’t work, we’d go into a studio. But in fact it was great. While touring, we would mutate songs. From the beginning we were doing it, but now it was really evident from one concert to the next.

Did you take that improvisational approach into the writing and recording of the album?

Yeah. And we used the acoustics of the house. We were playing in this drawing room to begin with, and then John Bonham had another drum kit set up in the hall, with this really high ceiling. When he started playing I said, ‘Right, we’ll have to do something in here now.’ The drum sound in that hall was just huge. You’ve heard it – on When The Levee Breaks. So we were moving from drums in the hall to drums back in another area, and really using the acoustics of the building.

Did you have a way of preparing for a take, for getting in the right headspace?

Collectively – absolutely. This is how we managed to record so quickly and efficiently. At any time there would be a few songs that you’re working on. But working on one number to record, we’d get it up to a serious speed, so it’s really firing on all cylinders and the real essence of the song is cooking, and then you’d start recording. It was very easy to get to that point, because you’re already rehearsed, but with the red light on there’s even more urgency to it. We’d arrive at those takes in a pretty short time – just a handful of takes, maybe.

What if a song just wasn’t working?

If a song started to labour, if the essence wasn’t happening, we’d stop and do something else. We didn’t over-rehearse. We just had them so that they were just right, so that there was this tension – you know, ‘Maybe there might be a mistake. But there won’t be, because this is how we’re all going to do it, and it’s going to work!’ That was a measure of how good everybody was in this band. And because of that, you could get these ‘character’ numbers through the whole of the Zeppelin soundscape. Each song has its own character. Theoretically, there was nothing we couldn’t do, because musically we were all capable of doing anything. Together, I mean. We didn’t need to get in horn sections or whatever. It was all in-house.

Did you feel that you were pushing the envelope with this album?

The whole history of Led Zeppelin is musical expansion. We were really pioneering in every way, I think. And with this album, we were moving the acoustic aspect of what we’d done on the third album into these more intimate areas with Going To California and The Battle Of Evermore.

When I interviewed you in 1993, you said that with Stairway To Heaven you set out to make a “profound” piece of music. Did that make it a difficult song to write?

I had the sections for it. It was a question of piecing them together. But by nature of the fact that it had acceleration through it, it needed some work on it. There was a lot to remember in Stairway, when you were playing it and routining the track.

You also said that Robert wrote the lyrics for Stairway To Heaven very quickly, while you were at Headley Grange, with the band working on the arrangement.

I can say – he’ll probably deny it, ha ha – but during the running through of Stairway, I remember Robert was sitting down in the room and he was writing and writing. At the point where he came to sing it he had a major percentage of the lyrics already done. And he went home and tweaked things. That’s how it was. That’s what the whole magic of the environment was like. Everybody’s creative energies were all joined.

Over the years, Robert has made light of those lyrics, as if he were embarrassed by the naivety in them. But the words in that song are very evocative, very deep.

They are. They come at you on many levels. I thought his lyrics were superb. So… maybe we all criticise our past work. I’m not going to tell you what, but I could say, ‘Well, I could have played better guitar on such and such a number.’ But I ain’t gonna do that, because it is what it is.

Is it true that you would record your solos alone, in complete isolation?

Always. I’d use the same approach as doing the tracks. I’d try to put the solo on at the end, because I wanted it to be totally in character of what’s going on with the lyrics. What I’d do is just limber up, limber up, limber up and then, “Okay, put the red light on.” Those solos weren’t done over hours and hours. I’d know if I was there with it. And they were pretty much improvised. They weren’t worked out note for note. Never. The solos were always… take a deep breath and go for it. I might have worked out how I might start it off, but that’s it. The solo for Stairway comes right into that equation.

Famously, there is a story that the release of the fourth album was delayed because there was a problem with the mixing at Sunset Sound studios in Los Angeles.

There wasn’t really a delay. I was at Sunset Sound for much less than a week. I arrived there with [engineer] Andy Johns, and there was literally an earthquake going on when we walked through the airport. In the hotel you could feel the bed shaking with all the aftershocks. We were due to go into the studio, and I said, “Okay, but we’re not going to do Going To California till the end.”

Why not?

Because the lyrics in that song were talking about an earthquake, and we’ve just arrived during an earthquake! But I wasn’t going to turn around and go back to England. It was just Andy Johns and myself, and Sunset Sound was a superb studio. We mixed a lot of the stuff that was done at Headley. But the only evidence you’d know of the Sunset Sound recordings up to now would be When The Levee Breaks, because that was the version that went on the album.

It has it been reported that the Sunset Sound sessions were a disaster.

How could it be a disaster if you’ve heard When The Levee Breaks? It’s all myth.

So why did you remix the album in the UK?

When the rest of the band heard the Sunset Sound mixes, they didn’t get it. So I said, “Okay, we’ll remix it again over here.” At Sunset Sound, the playback system was so colourful – really sort of high top-end and low bass-end. But when we came back and played it at Olympic [studio in London], where the speakers were very middle-y, suddenly the huge headroom had disappeared. That’s all it was – the monitor systems in each studio were so vastly different. It just needed a little bit of EQ mastering and it was fantastic.

On the companion disc included with the new reissue of IV, there is a previously unreleased mix of Stairway To Heaven from the Sunset Sound sessions.

What did you think of it? It’s Stairway. You’ve heard it a million times.

It sounds a little warmer, maybe a little cleaner.

Do you think so? Personally, I think it’s more of a hi-fi mix. It’s got that expanse, that headroom, a real depth to it. But that’s the whole thing about doing a companion disc. It just gives more information, more colours. I really thought that this is so important to do, to give all this extra information to the whole of the studio life of Led Zeppelin… for the fans. I know what they love. I know why there’s a bootleg industry out there. I’ve paid a lot of attention to what was out there on the bootleg market as far as studio material, because I wanted to make sure that what was going on these releases wasn’t already out there. I know that no one’s even heard the Stairway mix, apart from the band.

You first played Stairway To Heaven, Black Dog, Rock And Roll and Going To California live in Belfast on March 5, 1971, eight months before the album was released. Do you remember the reaction?

In Belfast at that time, there were the Troubles. I don’t know what sort of mix of Catholics and Protestants were in that hall in Belfast, but the response to everything was fantastic. And here’s the key point. You’ve just said that we went over there before the album was released. You couldn’t do that now. The whole intrigue and mystery of it would be blown because people would be publishing it on YouTube, all the new numbers. But in those days it was really good, because things would just travel by word of mouth.

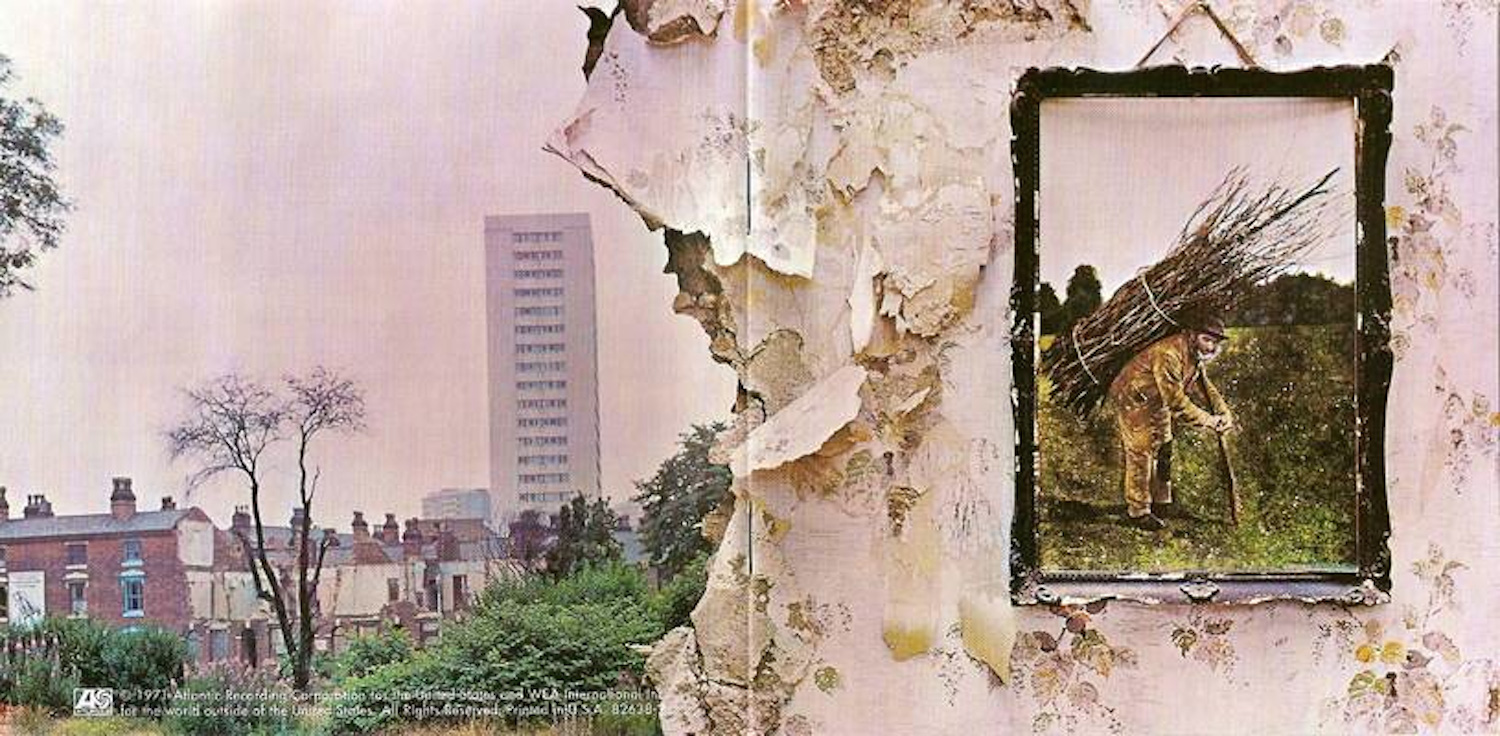

**When that fourth album was released on November 8, 1971, there was no band name and album title on the cover. **

It was my idea to have no title. It was a novel idea to put something out which had no title on it, rather than, oh, it’s just selling on the name.

The album is officially untitled yet it goes by various names: Led Zep IV, ‘Four Symbols’, and also ‘Zoso’, after your symbol…

I think it’s good that everyone calls it different things. With the [Zoso] symbol, people were calling it that, and that was a bit upsetting for the rest of the band [laughs]. It wasn’t intended to be like that.

The bosses at Atlantic Records thought that an album with no title and no band name was tantamount to commercial suicide.

They did. I went over to New York with [Zep manager] Peter Grant, and Atlantic were determined to have some words on the cover. I knew they thought: he’s impossible to deal with, this one. But it was so right to do it.

That album cover is so iconic. Is it true that the painting on the album cover was found by Robert in an antique shop?

It is. When I was living in Pangbourne, I used to go around the junk shops, picking up all this Arts and Crafts-era furniture. On this one occasion Robert came with me and there it was, this painting.

The cover was symbolic: the painting of the old man on the wall of a demolished house, with modern high-rise blocks behind it.

The imagery there is the old making way for the new. Those new buildings don’t look new anymore. But that was the idea.

The way you sequenced this album – the juxtaposition of hard rock tracks and acoustic numbers – is expertly judged.

We were crafting albums for the album market, a certain league outside of pop singles. So it was important, I felt, to have the flow and the rise and fall of the music and the contrast, so that each song would have more impact against the other.

You placed Stairway To Heaven at the end of side one of the original LP. Did you think about having it at the end of side two as a grand finale?

No, no, no! Levee Breaks had to end it, because it was just so ominous and dense and it was just going to disturb people. After you’ve caressed them with Stairway, now you’re going to disturb them [laughs]. That’s what it’s all about – conjuring up all these different emotions.

That side one is probably the greatest side of vinyl in all of rock history: Black Dog, Rock And Roll, The Battle Of Evermore, Stairway To Heaven. Really, it’s unbeatable.

It is good, isn’t it? But with the whole album, you get the feeling of the creativity of this band. It’s just coming in with full force. It’s showing the whole picture of what this band is musically. These were really honest performances – performances that you feel. No doubt about it.

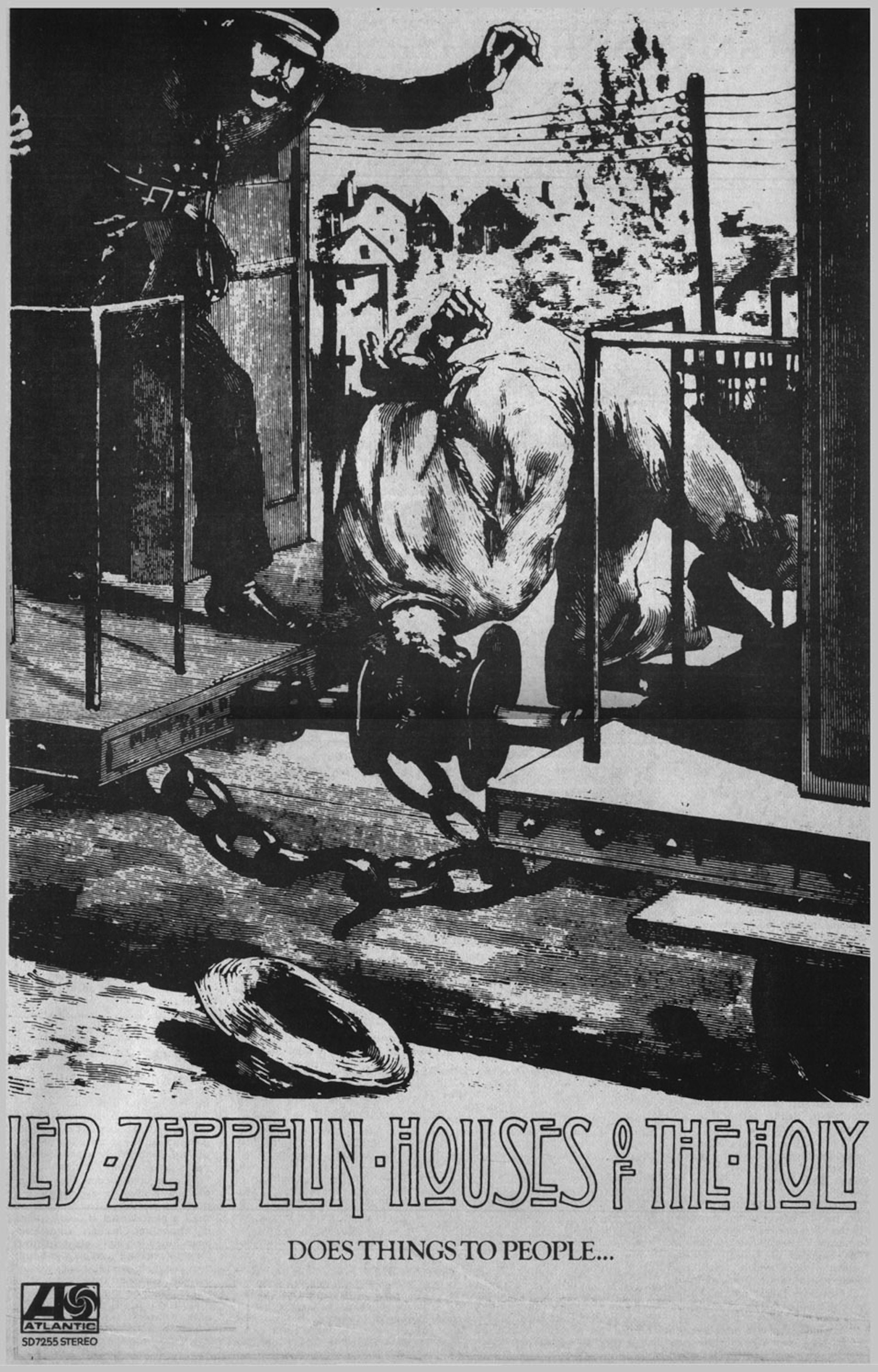

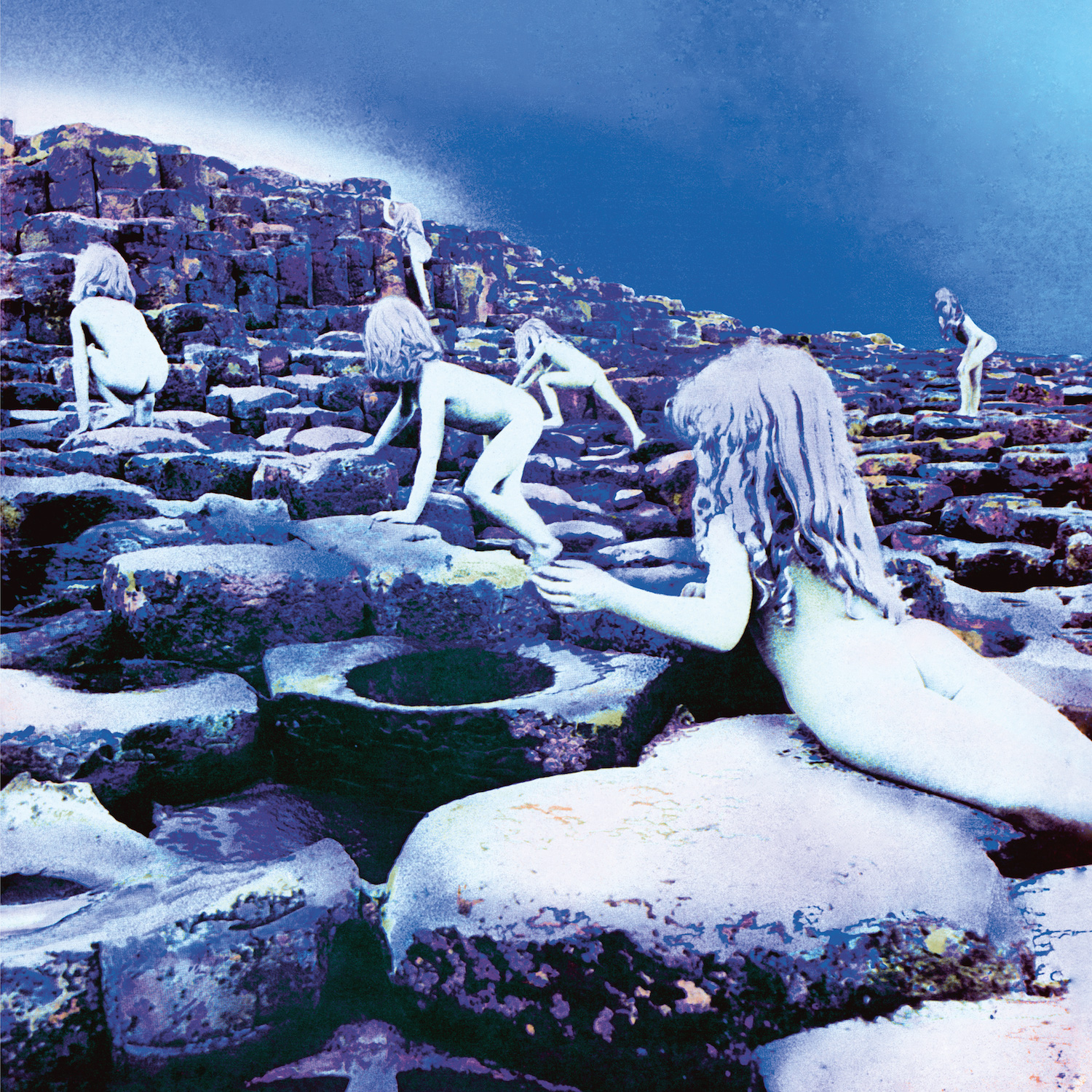

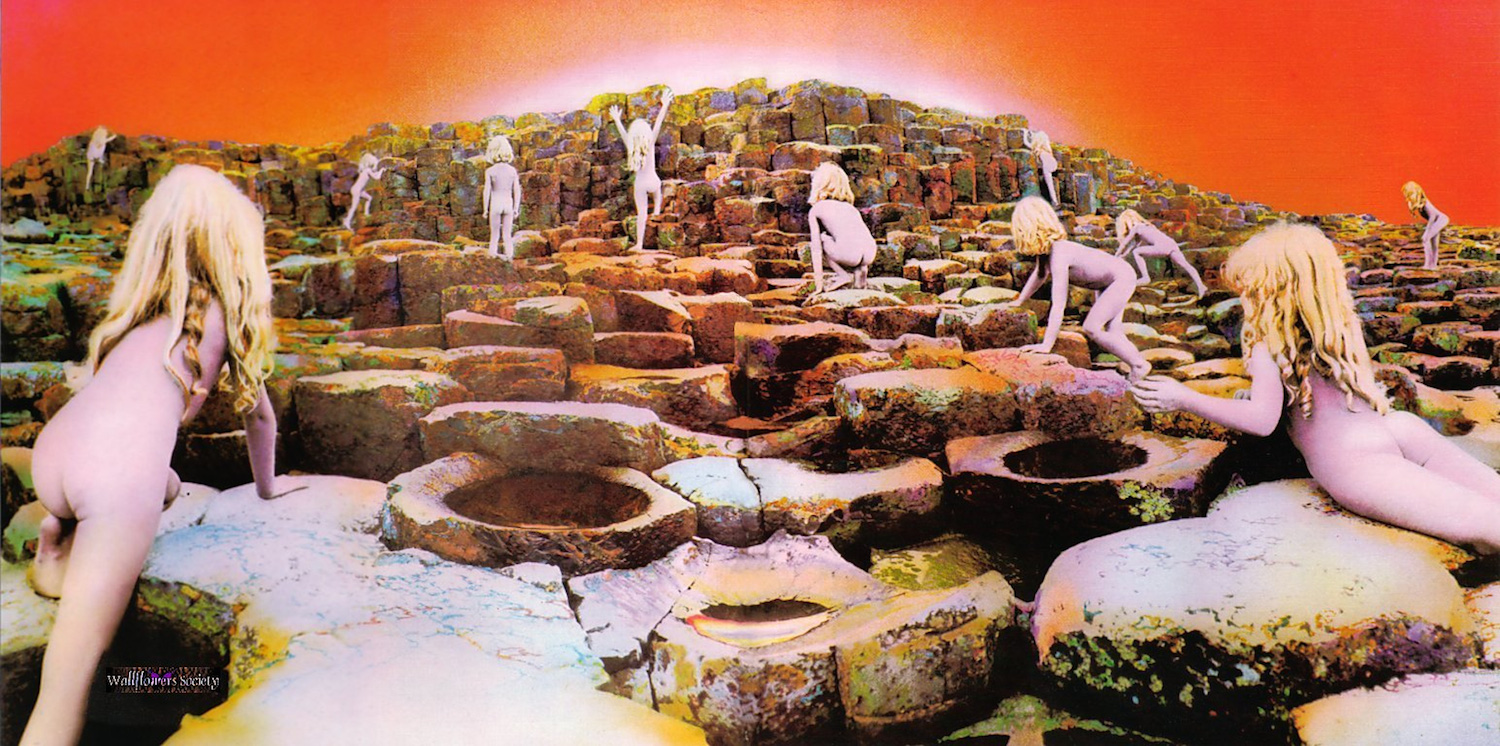

If Led Zeppelin’s fourth album was the band’s masterpiece, what followed was their unsung classic: Houses Of The Holy, released on March 28, 1973. In a sense, it was overshadowed by what came before and after it – IV and 1975’s monolithic Physical Graffiti – but it contained some of the most powerful tracks that Zeppelin ever created: No Quarter, The Rain Song, Over The Hills And Far Away, The Song Remains The Same. Adding to the mystique was the artwork created by Hipgnosis: a surreal image of naked children climbing the rocky terrain of the Giant’s Causeway in Northern Ireland, beneath a glowing yellow-orange sky. “It’s evocative, isn’t it?” says Page. “Its innocence, and the idea of us all being vessels of houses of the holy.”

The story goes that you rejected the original artwork submitted by Hipgnosis’ Storm Thorgerson, and then turned to their other designer, Aubrey ‘Po’ Powell.

Well, we got on better with Po than with Storm, but that’s how they were. If people didn’t like one person they’d work with the other one.

Did you know that the children on the cover are Stefan Gates, now a TV presenter, and his sister Samantha?

I heard it was Sam Fox. So it’s not true, then?

That old story about Sam Fox? Most people dismissed that as just another urban myth about Zeppelin.

I thought it made sense because she probably was put in an agency as a child model and all that.

Perhaps you could verify another story about Houses Of The Holy – that you wrote The Rain Song after George Harrison complained to you that Zeppelin never do ballads.

No, it wasn’t from George Harrison. He didn’t say it to me. I just heard it on the grapevine that he had said, “Oh, Led Zeppelin don’t do any ballads.” I’m paraphrasing, but it was something similar to that. He probably said it lightheartedly. He probably hadn’t really listened to very much Led Zeppelin.

There is also a similarity, in the opening notes of The Rain Song, to Harrison’s classic Beatles song Something.

Yeah [laughs]. I thought it would be interesting to put the first two notes from Something into the beginning of The Rain Song. But I thought that The Rain Song was really nothing like Something, so nobody was even going to think of it.

There is such beauty in The Rain Song. Do you consider it one of your best?

As a whole piece, yes, it’s pretty up there, for sure. As a guitar piece it was really good, but again, it came to life with Bonzo playing really sensitively on the brushes.

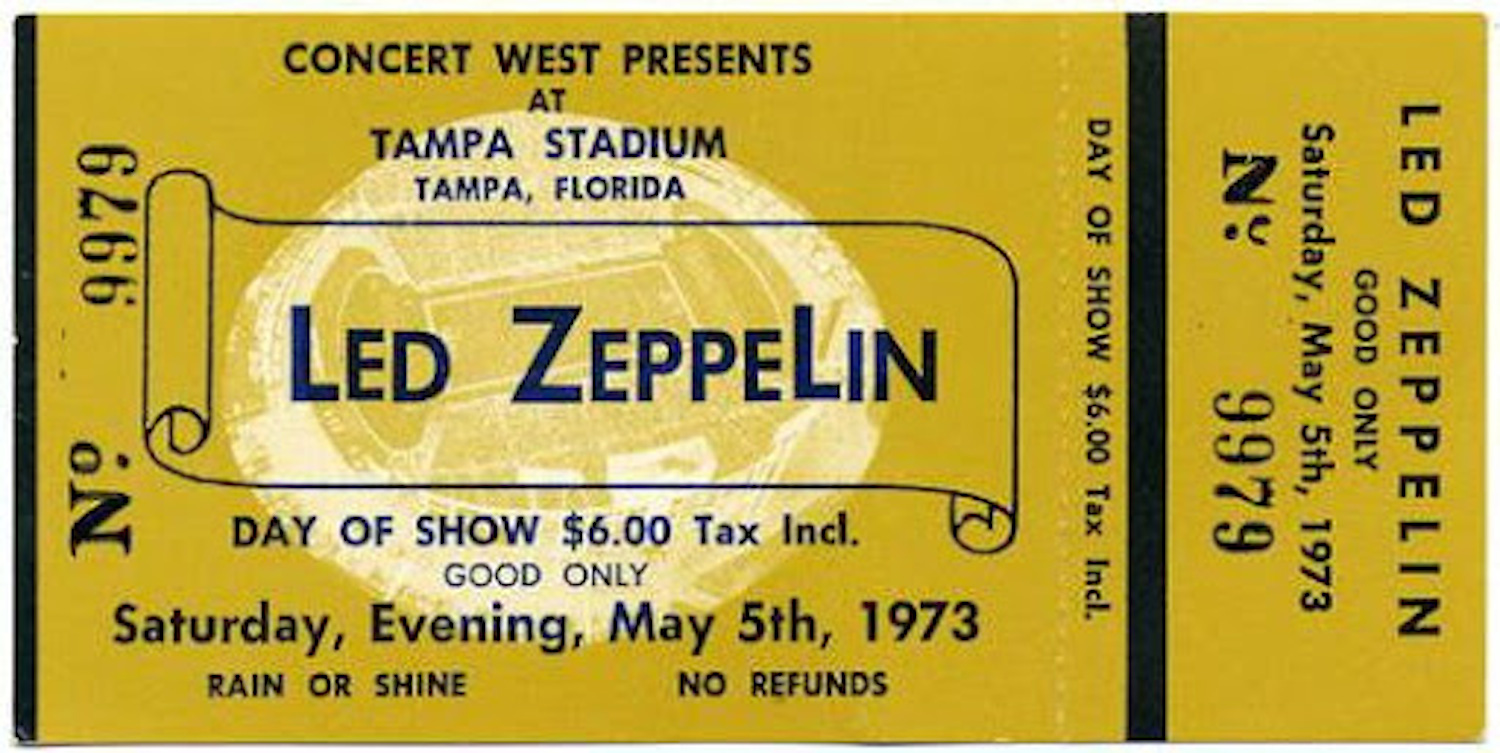

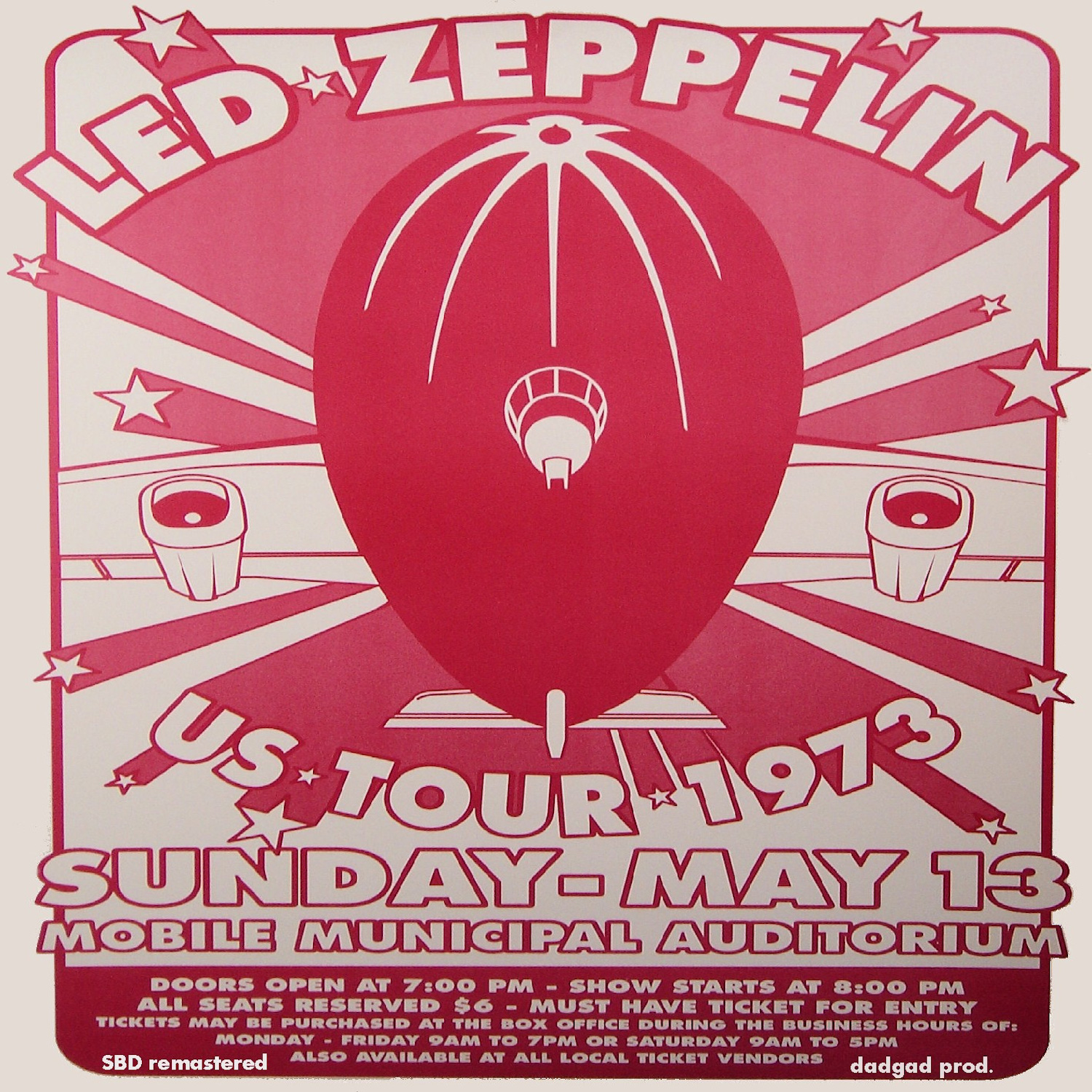

On the Houses Of The Holy tour, in the summer of ’73, Zeppelin’s gig at Tampa Stadium broke the attendance record that had been held by The Beatles.

What was it, 52,000?

More. 56,800, to be precise.

Well, we’d played fifty-something thousand the day before in Atlanta. Then we went into this huge thing in Tampa, where your main worry is, can everybody at the back hear what we’re doing?

Going on stage for such huge audiences, were you ever nervous?

I always had an edge, what you might call nerves, going on wherever it was. I wondered whether it was just the adrenaline. But I’d always get that sort of edge. There’s no doubt about it – you suddenly go into this sort of change, which you might call stage fright. But I was more realistic about what it probably was. It wasn’t being frightened on stage. I love being on stage. There’s nothing to be frightened about. But there was this edginess, sure.

With all the heavy touring that Zeppelin did in the 70s, doing three-hour sets, what kept you going? Was it that the music elevated you?

The whole set just kept stretching, because we loved playing. We could have just done an hour and a half, but we didn’t. We wanted to give everybody everything that we could every night. We were totally committed in the ethic of doing that.

Let’s talk about your life at this time. With all the work and the success and everything that came with it, did you ever feel disoriented?

No, nothing like that. It was all just a natural progression. In retrospect, if you look at the work we did, you think, Wow, how was that done? But, you know, we were all pretty young. I wouldn’t be able to take on a workload like that now – all that touring, five nights a week and the rest of it. But I was young. It was perfectly natural. That’s all there is to it.

Did Zeppelin’s fame at that point ever feel overwhelming, even frightening?

No. The whole climate was different then, wasn’t it? When you’re talking about that sort of passion from the fans, the way that it would be manifested was simply that the concerts just got bigger and bigger. So you could see, by the record sales as well, that the popularity was immense. And that was the manifestation of it, playing bigger shows and the response to it. And it never went away. The reality of Led Zeppelin, when you look at it all the way through, was that the audiences just kept swelling, right through to the end when we were doing Knebworth in 1980.

Who apart from the band would hear Zeppelin music before it was presented for release? Ahmet Ertegün, the head of your label?

[Flatly] He’d get the finished album. That’s how it was. It was wonderful, because it was so insular. You know what the climate was as far as what you had to do in those days. Literally what you had to do was make albums, then present them – with the cover – and then do more concerts. The record company wasn’t all over you. They couldn’t be all over you, because you’re telling them, “This is it – this is the new album.” And because of the demand for the Led Zeppelin albums, they couldn’t really get in the way. They didn’t want to get in the way of it. Because they could see – I guess history was proving itself – that we knew what we were doing.

Your power was your popularity?

Yes. And as you can see with the history, it was the right decision not to do singles along the way. That gave us the benefit to do exactly what we wanted to do, without having to think, Oh, what’s the single going to be? Or having some person from the record company saying, “Where’s the single?” Or even worse, saying, “I think you should do this!”

So there was never interference from them?

No. I’d lived through it with The Yardbirds, and I knew the climate wasn’t right for that.

Were you as much of a perfectionist in terms of business as you were with the music?

God, no! But that perfectionism applied to everything, to be honest.

Being such a perfectionist, were you a difficult person to work with?

No. I don’t think I was at all.

Did you ever sense that the band thought you were driving them too hard?

I don’t know if anyone thought I was. You’re always trying to strive to be better and better and better. That’s all there is to it. And sometimes, whatever you’ve done isn’t good enough. Do better, do better. But, you know, that’s my own thing. And I haven’t changed. That’s how I am.

In the 34 years since Led Zeppelin disbanded following the death of John Bonham, Page has continued to make music, albeit on a limited scale. There have been collaborations with Paul Rodgers and David Coverdale, and even with his old foil Robert Plant – the pair played on each other’s solo albums before officially reuniting for two albums in the 90s, 1994’s Zep-reimagining No Quarter: Jimmy Page And Robert Plant Unledded, and 1999’s all-new Walking Into Clarksdale.

But Led Zeppelin remained part of his life throughout. Ever since 1982’s archive collection Coda, Page has served as the curator and the guardian of the band’s legacy. But now, seven years after their one-off reunion show, this is all that remains of Led Zeppelin: the past. And for Page, it is now time for a new challenge.

What does the future hold for you? In terms of the music you’re making now, does that necessitate having a band?

Yes. I’m not going to just go out and do concerts with one guitar or even two guitars – one electric and one acoustic.

If you’re going to make a new album…

Maybe…

If so, would it be similar to Outrider, on which you had three singers?

[Smiling] We’ll have to wait and see, won’t we? The music I’ve been writing, it’s got various moods to it, various textures. That isn’t going to change. So there will be real surprises within it, you know? But there would have to be. I wouldn’t really be happy about it unless there was. But I have got material. It’s sort of there. And in a way I’m really pleased that I haven’t recorded it yet.

Why?

Because it will still be good. If something’s good, it is good, isn’t it? Riffs and things – they’re either good or they’re not good.

Robert Plant was recently asked about the possibility of making a modern Zeppelin album. He said: “The weight of expectation is too great.” Do you understand where he’s coming from?

No. No, no. Because I’m not doing a modern Led Zeppelin album. I’m doing the music that will be a summing up of where I am at this point in time.

But do you get what Robert was saying? Do you feel that what you created with Led Zeppelin in the past is in some way a burden on you as you’re making new music?

Well, there is pressure. But then you have to put it in context with actually thinking of all that pressure that’s built up over all those decades and putting your arse on the line for one night at the O2. What sort of pressure is that? You can imagine what it was like for that show. You know, one shot. At least when you’re recording an album you’ve got more than one shot at the solo. So you just have to look at it like that. New music is new music. But it still has to be good. It has to be vital. It has to connect with people. It doesn’t want to be limp and half-hearted. It really needs to connect on one level or another, whether it’s got that intensity to it or it’s something that is more rhythmic or voodoo-like, or something that is more sensitive or caressing. And that is what you’re doing – you’re a musician. You’re not thinking about whether it’s paling in the shade of Led Zeppelin. What sort of nonsense is that? [laughs] But you know what I’m saying.

Yes. But when we think back to Walking Into Clarksdale, your last original album…

Yeah, that’s like a minimalist album.

That was sixteen years ago.

Was that my last album?

Your last original album, yes.

Good. I’ve only ever had one solo album out in the past anyway, and that was in 1988. So I didn’t really try to cash in on the market, did I? I’ve done other projects along the way. I’ve worked with David Coverdale and this and that.

But do you feel that you’ve done enough?

Well, you can never do enough. But I don’t care. It doesn’t matter. It is what it is. And hopefully, next year I will be seen to be playing – because you need to be seen to be playing. That’s why I’ve put so much effort into stockpiling all of this new material. I know the importance of the Led Zeppelin legacy, if you like. So that’s why I’ve been stockpiling over a couple of years. I think it’s important. That’s the way to look at it and that’s the way to do it.

So do you need a singer to make this new music work?

Why, are you volunteering?

Come on, Jimmy. Don’t be silly.

Well, let’s put it this way: I don’t sing. I’ve said that on numerous occasions. I’m not a singer.

What is your singing voice like?

I don’t know. I haven’t really given it a shot, although I sort of sang many years ago, on the first Zeppelin album and a little bit on the second album.

But to answer the question about a singer…

You’re asking about what I’m going to do? Okay, let’s put it this way. What I would concentrate on would be the music that is going to be there. I wouldn’t approach whatever was going to be recorded in a flippant way at all. But I haven’t got any musicians ready at the moment to do anything, because it won’t be until next year that I’d even be able to do that. I’ve got so much promo to do relative to all of this [the Zeppelin reissues].

There’s one last thing I have to ask, and I know that it’s a pain in the arse…

Go on.

After the O2 show, you wanted to continue with Led Zeppelin, to do more shows. Robert did not. Seven years down the line, nothing has changed. Are you resigned to the fact that Led Zeppelin is finished and should fans just accept that too?

Yes, it’s time for me to move on to do other things. I’ve got a pretty fair old musical heritage. It goes way, way back to being a teenager. It goes all the way through from there to almost yesterday. I enjoy that. Ever since I was a kid, it was my passion to play music, to make music, and, you know, it makes people happy. If you do something as a living that makes people happy, you’re a very fortunate man. That’s bloody great. And I don’t mean this lightly when I say that is a wonderful lifetime achievement. That’s a great feeling.

For Jimmy Page, seven years of frustration have come to an end. After that O2 show, when Plant refused a Led Zeppelin tour – no matter how much money was on the table – Page, Jones and Jason Bonham rehearsed with Steven Tyler and Myles Kennedy. Whether they would have used the Led Zeppelin name, Page would not say. But in the end, nothing came of it. The subtext was quite simple: without Robert Plant, there is no Led Zeppelin.

In August 2014, Plant said of Page: “He should get on and do something. He’s a superb talent. Come on and give it to us.” Making new music, and playing it all over the world, is what Plant has done since that last Zeppelin performance. And now, belatedly, Page is gearing up do the same.

“I love making music,” Page says. “I love playing live. That’s it. That’s what I should be doing at this point in time. It’s ever onward now.”

Led Zeppelin IV and Houses Of The Holy are released in Deluxe and Super Deluxe editions on October 27 via Atlantic. See www.ledzeppelin.com

WANT MORE?

For Jimmy Page: 12 Unsung Page classics – click here.

For Jimmy’s early session years – click here.

For Jimmy’s solo album Outrider – click here.