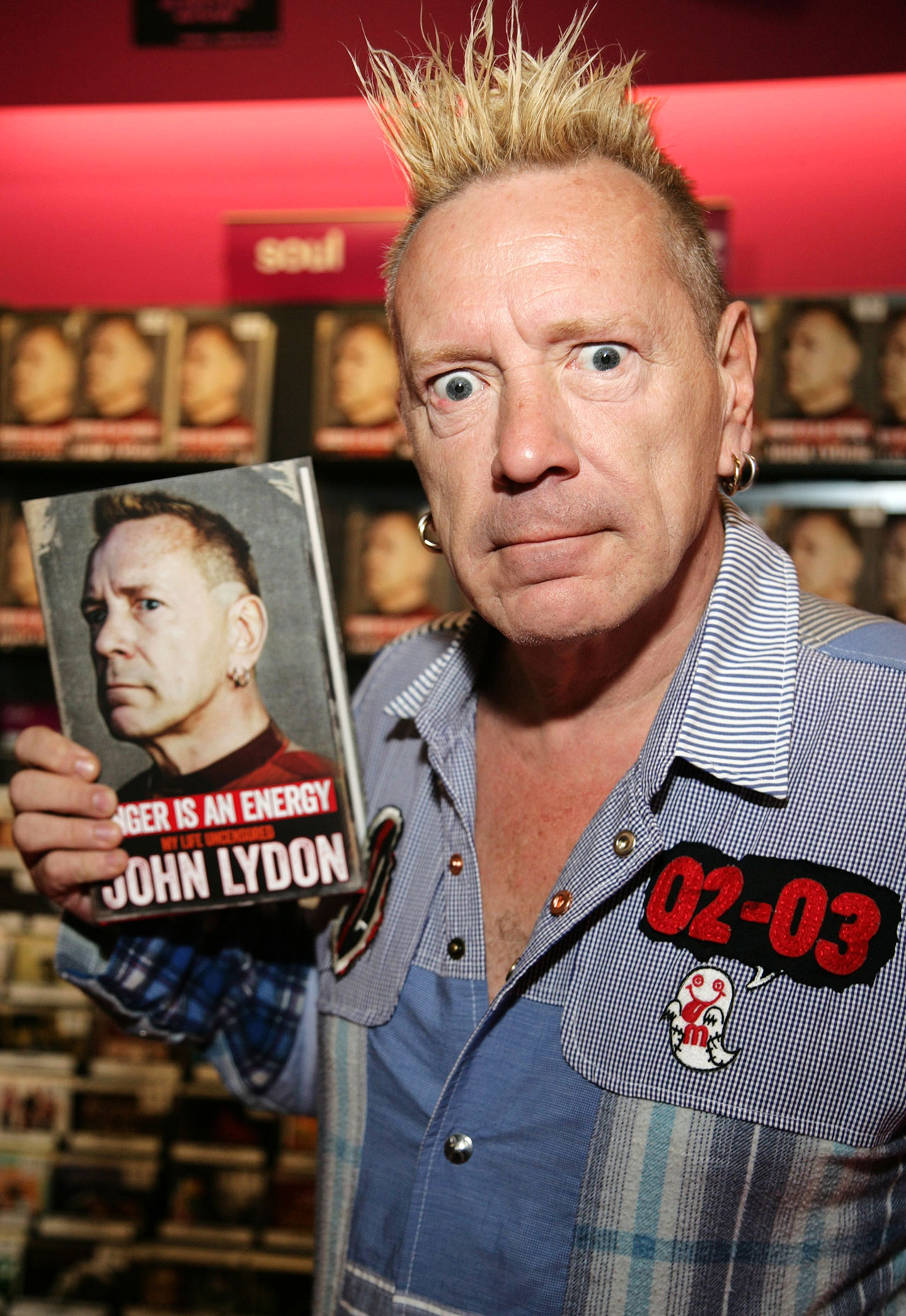

Former Sex Pistols vocalist and current PiL focal point John Lydon – opinion-polarising iconoclast of long standing – is tucking into a liquid brunch. Resplendent in billowing pink shirt, he’s perched on a Thameside balcony at Chelsea’s Harbour Hotel, smoking like a lab rat and lubricating a bright and breezy discourse with a rapid succession of minibar miniatures. Bourbon follows gin, follows vodka, follows bourbon… “Wanna brandy, mate?” It’s 11.45 on a Tuesday morning.

Lydon is animated (go figure) as he flicks through Mr Rotten’s Songbook, his eye-wateringly expensive, self-illustrated compendium of lyrics. Era-defining couplets and doodles in a distinctly Milligan style persistently prompt anecdotes, fury, melancholia, laughter and acid drops of obdurate bile.

The twinkle-eyed Lydon charm is habitually tempered by indefensible Rotten controversy – he’s nothing if not infuriating. And as he preaches his punk-inciting mischievous gospel, we realise why it is we can’t help but love this unlikely national treasure: he’s good bad, but he ain’t evil.

Songs are like machines

As I compiled Mr Rotten’s Songbook, I remembered the original writing of each song and what was floating around in my mind when I committed the lyrics to paper. When I write I have ideas running around in my head consistently, until I hear the right tone or noise and then I write to that. That spurs me on. I love writing. I love a choice phrase to explain a situation accurately.

Accuracy is intrinsic to me. It’s the heart, soul, mind, body, everything of writing. Telling a story, capturing a situation as best as you possibly can in as few words as possible. Being able to do that from my first band onwards was a real bonus. To be able to do it to music was an absolutely beautiful concept that was offered to me, and that turned into punk. I’d found the rivets that held the thing together, and that was a musical backdrop.

I always wanted to be a writer, but was never happy with words alone. I need a melody, a lilt, a sonorous or sometimes a malodorous structure in order to pin it down. I can also do that with cartoons and drawings. When we collected all my lyrics together, I looked through them and started doodling, illustrating how I remembered the situation surrounding certain songs, adding a fourth aspect of my personality to them, which is when they expanded into a book.

Lyrics set a band’s agenda

I don’t know if Malcolm [McLaren, Pistols manager] ever read the lyrics of Anarchy In The UK or God Save The Queen. I don’t know if any of them did. I just did what I did. I came in with my own imagery and wrote about aspects of life that completely altered the agenda, produced shock, awe and horror in the world. But it so needed it. From my point of view, these were the institutions, organisations, governments and religions that were ruining my life up to this point – ruining all of our lives. It wasn’t just my own personal point of view, it was an oppression all of us were under. We needed to break free from the shackles that were demanding blind obedience to a monarchy. Why can’t you question or challenge that? Why can’t you raise an issue with it? Well, I did.

I’m not the same as when I began

By the time I formed PiL I’d written enough, in great detail and accuracy, about institutions demanding your loyalties and all of that. I felt it was time to move into personal politics because I was questioning myself: did I have a valid place in all of this? I was facing ‘That’s the end of him!’ challenges from the media. They were out to stick their knives in my back, so I beat them to the punch [laughs]. I knew what my faults were, so all their negativity couldn’t hinder my progress. That’s when PiL went into self-exploration, studying emotions and what their value is. And as the years progress, so does my knowledge, and that helps the songs. Joining my first band all hinged on me wearing an ‘I Hate Pink Floyd’ T-shirt. Which I didn’t [laughs], so irony’s always been there too.

There’s strength in adversity

The most helpful part of my entire existence were those four years of complete confusion and isolation, lost in the wilderness [Lydon suffered a near fatal bout of spinal meningitis when aged just seven, which left him with severe memory loss]. It was really the most excellent gift that God or nature could have ever given me. I had the opportunity to view myself from the outside looking in and wonder who I really was. I discovered what a personality is, and how quickly a personality can be apparently removed because of lost memories. But your personality still exists – you still know you’re something, that you belong somewhere. There’s still some connection to your fellow human beings. It’s just what that connection is that took a long time for me to work out. But I learnt from that period, not to bother with lying and to believe everything that people tell me. But when I find out that they’re lying, that’s it, I’m done with them. I’ve gone.

Never trust a nun

When I desperately needed to remember who I was, some wicked adults lied to me and deceived me. I was left-handed from when I was born – I’ll always be left-handed. The only real physical trait that was still in existence when I came out of hospital was that I was left-handed, but the nuns that ran the primary school that I went to, the Sacred Heart on Eden Grove [Holloway], were trying to convince me: “No, you’ve always been right-handed.” This is hindering your progress and the most evil, spiteful thing you can do. They’d hit me with the sharp edge of a ruler, and that pain brought back the memory of being rulered the same way when I was younger. My memories were spurred on by anger, which is the energy.

Religion is pollution

I don’t know if I ever really believed in God, but it’s hemmed into you that you’re guilty no matter what you do, so you always feel shy and reserved about everything. Now that’s all gone, but there are moments of solitude where I can look back and remember just how painful, according to them, God can be. Organised religion is evil pollution. A parasite on our good nature that lulls us into a false sense of security and it stops us thinking for ourselves. Just like left- or right-wing politics, the modern religion.

A trained voice is a bland voice

You don’t need to follow vocal registers or limitations or styles of singing – you need to sing how you feel. And it takes a long time to get there. This takes me back to my first band again. I had to find a singing voice, immediately.

In them early days we didn’t really have monitors, so I never really heard myself until we were supporting Eddie And The Hot Rods at the 100 Club. They had monitors, and I was disgusted by what I was hearing [laughs], so a serious readjustment went on. I could never really understand why the band weren’t paying particular attention to what the words were, then I realised that the vocal sound was off.

I watch X Factor and American Idol, but only the auditions. I feel genuine pain and empathy for those poor souls – full of heart – that just ain’t there, and they’re not there because they haven’t been given the time to get there. Those shows would mean much more to me if they tried to develop someone from zero to hero, rather than letting trained singers waltz in and take over. A trained singer, to me, that’s just karaoke, just technique. There’s no heart and soul in it.

The music business kills bands

Large record labels poison you. Get rid of them. They mean well, but they infiltrate and tell one member a different thing to that which they tell another. Different sub-groups form, and it ends up with this kaleidoscope of catastrophe that creates poisonous agendas and jealousies. Then the commitment’s gone. That’s basically why Public Image has had what, forty-nine members over the years? When it comes to the crunch of making a second album, the record company have polluted all your minds against each other, everyone’s viewing themselves as a superstar and fancying their own solo careers, and then on top of that the record company withdraw the purse strings. It’s a bottomless pit of problems that goes on and on.

Band members don’t have to hate each other

From my first band onward, I thought: “Well, it’s adversity, isn’t it?” You know, Shakespeare: smile in the face of adversity [laughs]. You’re not supposed to like each other, but I knew deep down inside that wasn’t the right way. It took time, but now I’ve realised we can raise finance on our own just by gigging, and we appreciate each other. So now, for the first time in my life, I’ve made two albums with the same people. It’s a fantastic, heart‑warming feeling. And we will, some time before the end of this year, do a third, because there’s such a rich vein of ideas. Between us is a gold mine of great stuff and we’re knocking little nuggets out of each other that go towards the betterment of the songs. I never thought I’d be able to deal with the comfort zone, as we call it, which is really uncomfortable [laughs], but thrilling. It’s still a knife edge I’m on, just the other side of the knife.

Not all publicity is good publicity

Never was. Some of that Sex Pistols publicity got me discussed in the Houses of Parliament under the Traitors and Treasons Act, which carried a death penalty. I could have been condemned to death. I giggled all the way through that, though. In the end, the establishment pretty much harassed me out of the country. There were endless police raids. It wouldn’t stop and it became impossible to function, to do anything. You’d walk down the street – instant search. I don’t need this, my band don’t need this. Nobody needs this. It was ludicrous overreaction by the British establishment. They make their own demons and then they have to go to bed with those demons… And we roger them royally.

Super-Deluxe Editions of Public Image Ltd’s Metal Box and Album are out now via UMC.

What happened when the Sex Pistols appeared on the Bill Grundy show