This article originally appeared in Classic Rock #188.

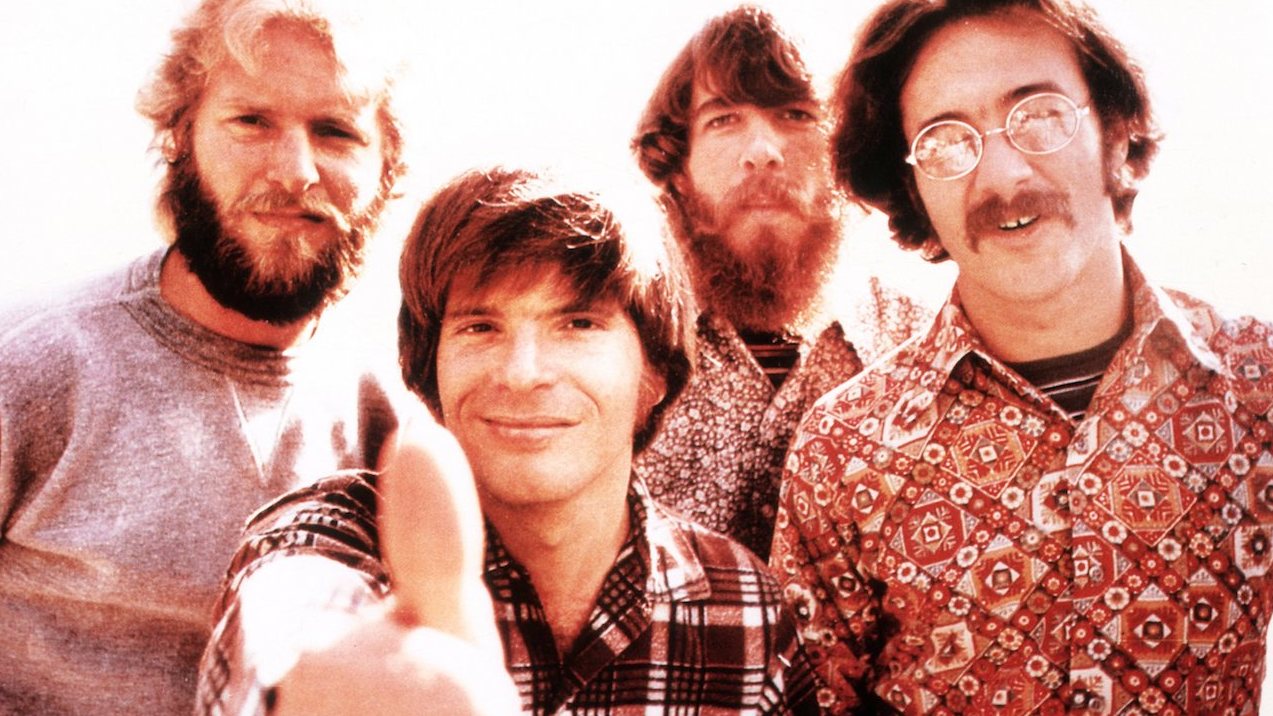

In May 1968, Creedence Clearwater Revival were booked at the bottom of a five-band bill at San Francisco’s Avalon Ballroom. The newly-named four-piece had been kicking around the scene in different incarnations for nearly ten years, but they were still a few months away from the debut single that would put them on the map. Taj Mahal, Dave Van Ronk and the two other bands ran through their soundchecks, leaving Creedence approximately four minutes to do theirs before the doors opened. Band leader John Fogerty plugged in and started to chop out a quavery rhythm on an E7 chord. John’s brother Tom, bassist Stu Cook and drummer Doug Clifford locked in behind him. In a flash of inspiration, one of their defining songs, Born On The Bayou, was born. And almost snuffed in the cradle, as it turned out.

“I was so excited that I was playing in front of a real audience in San Francisco, like any kid would be,” John Fogerty told American Songwriter this year. “I was just charged. And suddenly, I was inspired. It just kind of happened at once, and I turned to the band and said, ‘Just do this. Just follow this!’ And I just started screaming at the top of my range, just a melody and vowel sounds and consonants. It’s all sort of primitive, but I’m making noises. This is exactly how I write songs. This was happening right there. And then suddenly, nothing.”

Right in the middle of the creative roar, the stage manager pulled the plug on Fogerty’s amp, yelling that the band were wasting everyone’s time. “He said, ‘You’re not going anywhere anyhow,’” Fogerty recalled. “I looked at him and said, ‘Not going anywhere? Give me a year, pal.’”

Fogerty was good to his word. By mid-1969, Creedence were the hottest band in America. In that year alone, they accomplished more than most groups in their career. They had four Top 10 singles, three of which reached No.2. They released three classic albums, including Green River and Bayou Country, and played for close to a million people at arenas and festivals, including a headlining slot at Woodstock. Billboard awarded them Top Singles Artist, while Rolling Stone named them Best American Band. Give me a year, indeed.

But the Avalon stage manager wasn’t alone in his low estimation. “We were like Rodney Dangerfield – we didn’t get any respect,” Stu Cook tells Classic Rock with a laugh. “All these people in San Francisco, like the Dead and the Airplane, who’d been in folk bands and were now hanging out at Golden Gate Park and the Haight-Ashbury, they had their own thing going. We were out of sync, the guys from the East Bay who had a completely different take on the kind of music we wanted to play. We’d been working hard at it since the late 50s. While we had a psychedelic moment with Suzie Q, which gave us a little bit of cred as a band you could trip out to, most of our stuff was focused on singles. For years, wherever we played – state fairs, frat parties – it was singles. That was our specialty. John was a huge fan of the three-minute-or-less story.”

Fogerty was not only a huge fan but a dedicated student. Much of his youth was spent in the family basement, hunched over his record player, dissecting singles by everyone from Carl Perkins to Ray Charles. As he said in 1970, “As a songwriter, I think in terms of the Top 40. That’s where the tunes are. A single means you’ve got to get it across in a very few minutes. You don’t have each side of an LP. We learned from the singles market not to put a bunch of padding on your album. Each song’s got to go someplace.”

The first Fogerty song to really go someplace was Proud Mary. In a trick he’d repeat many times over, he struck a balance between unshakeable guitar riff, pop smarts and screaming rock’n’roll. “It was John’s first real Tin Pan Alley kind of tune,” remarks Cook, “with a beginning, middle and end. And the track has a very laid-back feel, very greasy. A really deep groove.”

Written in joy after Fogerty received his honourable discharge from the army, Mary rolled up the charts in March 1969, the same month Sgt. Pepper fell off the charts after eighteen months, the Jimi Hendrix Experience were splitting and Jim Morrison was arrested for exposing himself. Did Creedence have the sense they were stepping up as the next big thing?

“We were right in the midst of some kind of American revolution,” says Cook. “But being in the middle of it, I don’t think we were aware that the music scene was changing. The psychedelic thing was still going on with all of the bands that reigned at the ballrooms in San Francisco. I think they were surprised that the four guys who didn’t hang out and get high all the time were suddenly getting so far ahead. But then we weren’t a San Francisco band. We came out of the Bay area. When we went national and international, we weren’t part of any one scene. We were part of a larger American music scene.”

While this is true, Fogerty mined the gold of Creedence’s music and lyrics from one geographical area: the Deep South. The imagery of bullfrogs, bayous, backwoods and ‘Barefoot girls dancing in the moonlight’, coupled with Fogerty’s delta bluesman howl, gave the band their unique identity. Slightly incongruous coming from a kid who’d never stepped foot in Mississippi, sure, but what the critics dubbed ‘swamp rock’ was part of Fogerty’s well-laid plan.

“All the really great records or people who made them somehow came from Memphis or Louisiana or somewhere along the Mississippi River,” Fogerty said in the CCR biography Bad Moon Rising. “I had a lifelong dream that I wanted to live there. I never even thought about the social pressures. To me, it just represented something earlier, before computers and machinery complicated everything, when things were calm and relaxed. And singers like Howlin’ Wolf and Muddy Waters gave me the feeling that they were right there, standing by the river. The South just seem to be where all the music that’s kicked everything off started from.

“I put the music in the swamp where, of course, I had never lived,” Fogerty continued. “I was trying to be a pure writer, no guitar in hand, visualising and looking at the bare walls of my apartment. Chasing down a hoodoo. Hoodoo is a magical, mystical, spiritual, non-defined apparition, like a ghost or a shadow, not necessarily evil, but otherworldly.”

He found the hoodoo in evergreen classics like Born On The Bayou (and put the ‘hoodoo’ into the lyric), Green River and Bad Moon Rising. Even the titles sound like they could double as plays by Tennessee Williams. Earthy, mysterious and, for a world that wasn’t yet globally connected, exotic and alluring.

The band rallied behind Fogerty’s vision. Cook recalls, “We’d sit every morning before rehearsal, talking about the sound and direction of the band. John suggested that we really mine the roots of rural and urban American black music, which was our favourite kind of music anyhow. We’d all grown up together, listening to it for years. The whole thing of the south gave John great imagery to work with. John led, and each of us was there to do our part in putting this vision across.”

- The Story Behind The Song: Bad Moon Rising by Creedence Clearwater Revival

- Nine obscure Creedence facts

- Creedence men sue Fogerty over name

- John Fogerty: Wrote A Song For Everyone

Putting it across was hard work, but Creedence applied themselves with fervour. From their proto-grunge flannel-and-jeans to their drug-free lifestyle, they were like working-class soldiers pledged in the service of swamp rock. Nowhere was this discipline more effective than in the studio.

“My basic philosophy is that you’ve got to have it sounding like what you want right there in the room,” Fogerty said in Bad Moon Rising. “That’s where it all happens. Then it’s up to the engineer and the producer – who was me – to get it down on tape.

“It was no accident that we got that sound. We all felt it had to have the muscle and the subtleties we were looking for, and we spent a lot of time looking at snare drums and going through bass strings and bass amps and all that. The idea of fixing it in the mix is totally foreign to me. Same with singing. I’d go in there and probably do two takes, and that would be it.”

Cook adds, “Even way back then when recording was primitive, it cost a lot of money to go into a studio. More than we could afford. So we never thought of it as place where you experimented. We were really focused and well-rehearsed. When we went in the studio, we expected a result and we got the result. Every time we went in, we got better. So by the time we started having hits, we were super efficient. We could lock into those laid-back, greasy grooves instantly.”

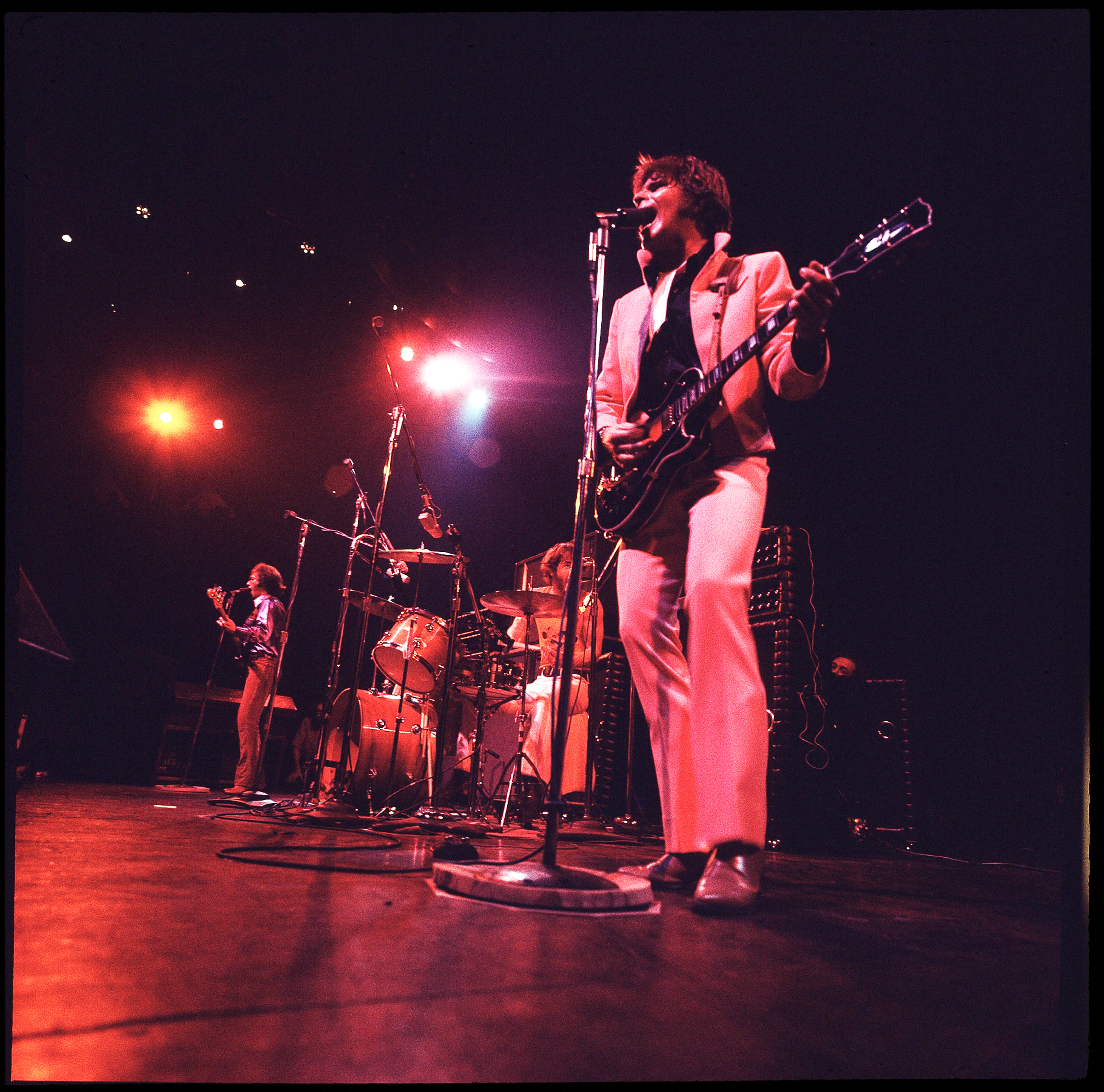

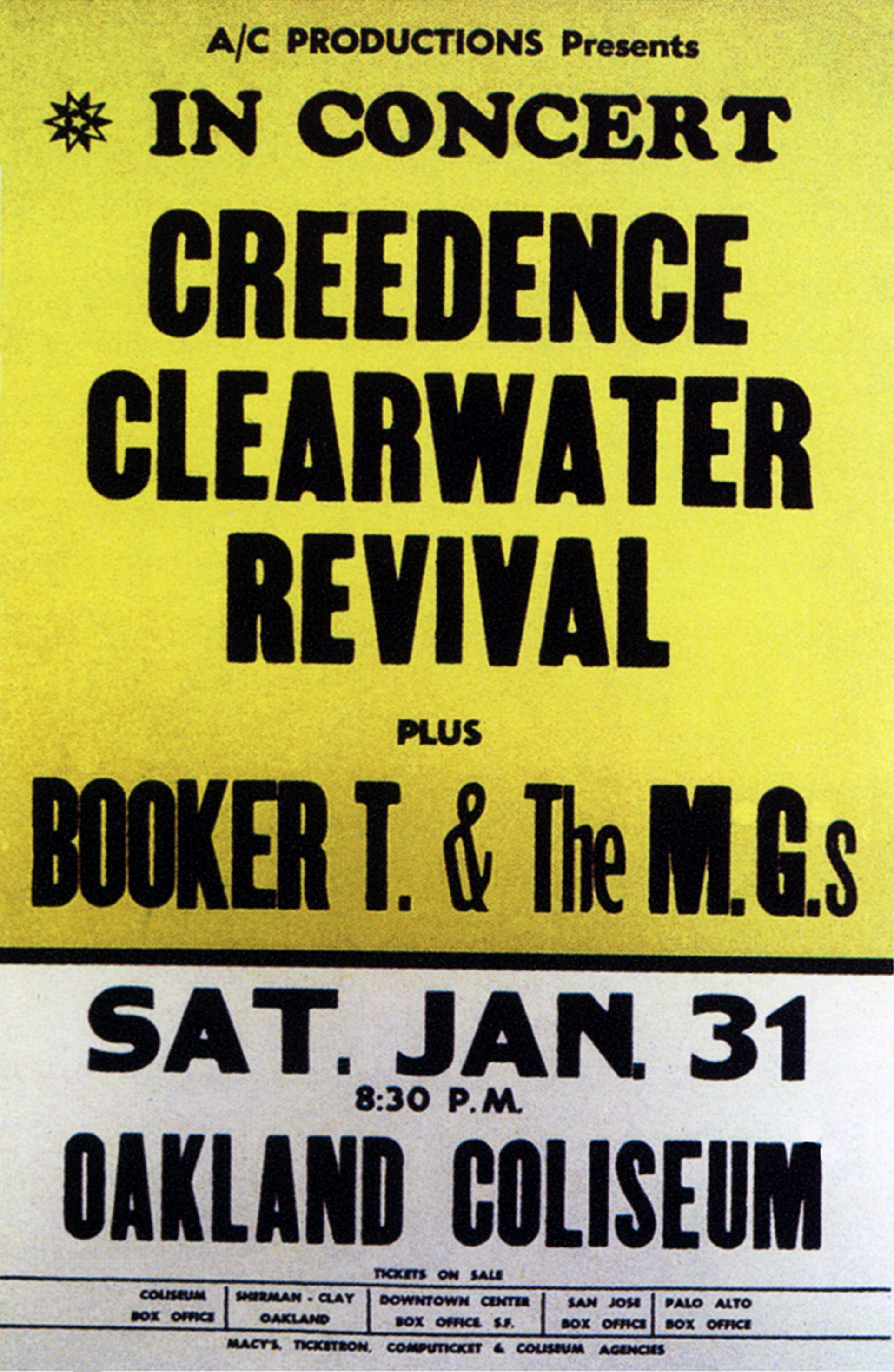

With the groove machine firing on all cylinders through 1969 – what Cook calls “the great gush period” – Creedence graduated from 50-watt amps to stacks, from a Volkswagen Bus to a Lear Jet, playing with The Byrds and Mothers Of Invention while also headlining large venues like the Hollywood Bowl and Mile High Stadium. But the big stage wasn’t always a comfortable fit.

“I don’t know that we ever made the jump,” admits Cook. “We were a garage band from our inception, and we worked hard at our craft. But I think we were at our best on a smaller stage, closer to an audience that was really paying attention. When you get on a stage that’s 40-feet wide, you kind of lose touch with each other. It’s harder to get the feeling across. It’s more of a spectacle. What’s going on in the audience, who can tell? And Woodstock was the epitome of that. My favourite quote about that show comes from Gregg Rolie: ‘It’s all hair and teeth after the first 20 rows.’”

At Woodstock, CCR took the stage at 3am, after the Grateful Dead’s marathon jam had lulled most to sleep. Fogerty recalled in Bad Moon Rising, “It was like a painting of a Dante scene, just bodies from hell, all intertwined and asleep, covered with mud.” He zoomed in on one guy flicking his Bic a quarter-mile back and played to him.

While the resulting film and soundtrack of Woodstock sent several careers to the next level – Santana, CSN, Ten Years After – Fogerty opted out: “I did not feel that the performance was our best and did not believe it would be good for it to be included in the film.”

However, Cook disagrees.“Those are classic Creedence performances,” he argues. “I’m still amazed by how many people don’t even know we were one of the headliners at Woodstock.”

As 1970 dawned, Creedence motored through their frequent differences of opinion and kept the radio hits coming. (Is there a more electrifying intro in rock than Up Around The Bend or a better feelgood tune than Lookin’ Out My Back Door?) They also brought their American swamp thing to ecstatic crowds in Europe and Australia, enjoying many rock-star moments along the way – hanging out with the Moody Blues, making a narrow Hard Day’s Night-style car escape from rabid fans in Germany and partying with Led Zeppelin.

“With Zeppelin, we ended up trashing a hotel in Adelaide,” Cook says. “It cost us about $2,000 to get out of there. But that kind of thing didn’t happen very often. 1969 and ’70 was really about three things – touring, recording, recovering. It was a pretty fast rocket ride.”

What’s unfortunate is that the band couldn’t quite enjoy the ride. “We were walking the tightrope between fire and ice,” Fogerty said in Bad Moon Rising. “I was desperately worried we were about to fall flat on our faces. In those days, you put out singles every few weeks, so I knew we had to write the next one.”

“As exciting as it was, it always felt like we were pushing a rock up the hill,” sighs Cook. “Our record company wasn’t much of a company compared to the real labels. Fantasy was a small, Bay Area jazz label, a catalogue label. They weren’t signing anyone. They didn’t have a promotion team. They weren’t in step with the 60s and 70s at all. They were like a bunch of beatniks from the 50s. If it wasn’t for Top 40 radio and our fans who liked the music, who knows what would’ve happened? Probably nothing.”

By 1971, Fantasy Records’ questionable accounting was one of many factors that led to the band’s implosion. Tom Fogerty’s sudden departure, John’s dictatorial leadership and insistence on handling their affairs himself, the group’s fights over shared creative input – it all spelled trouble. Of course, CCR’s bitter split in 1972 and the decades-long feuds and legal battles have been documented, as Cook says, “ad nauseam, and that’s why I prefer to think about the good times.”

He and Doug Clifford now tour with Creedence Clearwater Revisited (John tried to block them in court from using the name), keeping the old hits alive for audiences “from eight to 80”. Meanwhile, Fogerty indulged in some nostalgia with this year’s duets album, I Wrote A Song For Everyone, remaking his classic tunes alongside vocal partners from Bob Seger to Foo Fighters to Miranda Lambert.

As Fogerty tells Classic Rock: “I’m a lucky man that these songs are still loved around the world. But if there’s anything that I could imagine about why, I think it’s because my songs were very pure. I tried to speak very directly without a lot of words. And I try to make simple but powerful music.”

Pure, simple, powerful. That’s Creedence Clearwater Revival in three words. And that combination has helped their music endure for over 40 years.

Cook says, “Relative to other bands of the era, Creedence haven’t sold that many millions of albums, but I’m constantly amazed at how deep and broad our fanbase it. More so than artists who have sold way more than we have.”