Manic Street Preachers’ masterpiece, The Holy Bible was so much more than just a rock album. In a musical landscape in which grunge was reaching the end of its glory days and Britpop was on the rise, it was an anomaly and an education, a reading list, a warning from history.

It offered art appreciation, political studies, and sent so many of us running into the arms of Sylvia Plath, George Orwell and JG Ballard, scouring local libraries for the authors and novels it referenced. It offered kinship, a haven of deep thought and raw, often uncomfortable honesty that acknowledged the emotional struggles and political questioning that come as part and parcel of the teenage experience. As the boorish laddishness of bands like Oasis began to take over, to some of us it was not just welcome, it was essential.

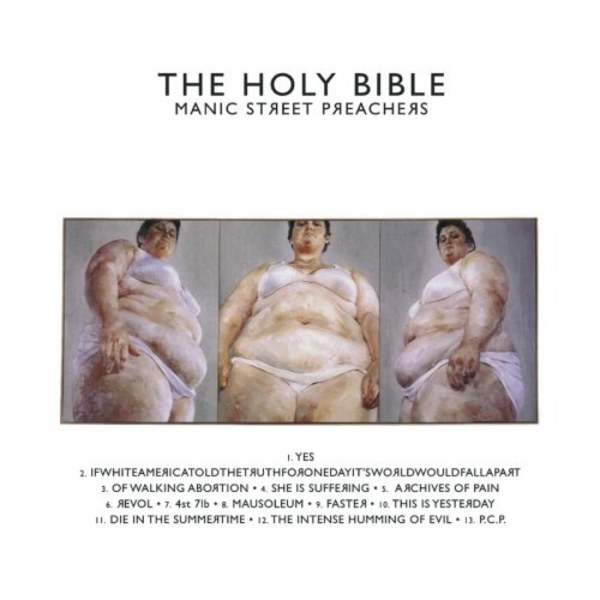

The shock of the new came from a first glimpse of the artwork. Artist Jenny Saville’s Strategy (South Face/Front Face/North Face) features a large woman in her underwear, examining herself from three different angles, a breathtaking challenge to the male gaze that has dominated the art world for centuries. When Richey Edwards (Richey James in the sleevenotes) sat down with Saville to explain the meanings behind the songs and the album’s overarching themes, she agreed to let them use the image for free.

Meanwhile, the back sleeve carried a quote from Octave Mirbeau’s The Torture Garden, a hint of the extent of the literary influences at play on the record itself, while the photographs of the band showed an entirely new mood – the bright leopard-print, eyeliner and spraypaint of their early days ousted in favour of a look that was military, beautiful, doomed.

The Holy Bible is the point at which the so-called Cult of Richey reached its peak, and it is undoubtedly his record, although he didn’t play a note on it. Previously he and bassist Nicky Wire had evenly shared lyric-writing duties, but here he took the lion’s share. Suffering depression, alcohol abuse, self-harm and anorexia, his bleak take on the world appeared to come from his own inner turmoil and his despairing view of the brutal history of the human race, taking on everything from serial killers and mob rule to small lives lived under right-wing totalitarian rule.

The words came in such a torrent you can hear frontman James Dean Bradfield tying himself in knots trying to fit them all in, from the tongue-twister dealing with prostitution and sexual exploitation in Yes to Faster, still one of the band’s most magnificent moments as self disgust meets a panicked self-aggrandisement: 'I am stronger than Mensa, Miller and Mailer/I spat out Plath and Pinter.'

When they performed the song on Top Of The Pops the show was inundated with kneejerk complaints, as Bradfield elected to wear the kind of balaclava synonymous with the IRA – although the fact that he’d scrawled his name across the forehead made it all somewhat less threatening.

Faster itself begins with a sample of John Hurt’s Winston Smith in the film adaptation of George Orwell’s Nineteen Eighty-Four: "I hate purity. Hate goodness. I don't want virtue to exist anywhere. I want everyone corrupt." The quotes and clips that pepper the album are an essential element, adding a human voice to subjects almost too weighty to approach. And so The Intense Humming Of Evil, inspired by the band’s visit to the concentration camps at Dachau and Belsen, begins with a report on the Nuremberg Trials, opening up to the bleakest few minutes you’re ever likely to hear on a mainstream rock record.

It’s also a perfect example of how the band had moved on musically. While their debut Generation Terrorists was their unashamedly glam classic rock moment, and Gold Against The Soul was a polished exercise in hard rock, The Holy Bible saw Bradfield and drummer Sean Moore take their inspiration from the shadowy edges of post punk: Joy Division, Magazine, Wire, Siouxsie And The Banshees.

And so while there are plenty of moments they let loose, with the frantic Yes, the aforementioned Faster and Revol, a blazing gallop through the sexual peccadillos of world leaders and dictators, there are moments so stripped back to the bone the pain is palpable. 4st 7lb, in particular, is a tough listen, Edwards’ portrait of the anorexia he was suffering via the avatar of a teenage girl. Beginning with a heartbreaking sample from a documentary called Caraline's Story and drifting into a sick euphoria that becomes more and more delicate as she wastes away, it’s a masterclass in restraint and musical sensitivity.

Just five months later, Edwards disappeared, leaving his car parked close to the Severn Bridge. A tragic postscript to a deeply personal piece of work with so much intellect and humanity, it means The Holy Bible will, sadly, always be viewed through the lens of what happened after its completion.

But it’s a record to celebrate and treasure, and to revisit on a regular basis. As teenagers dotted in grey provincial towns across the UK, it was our library, our art gallery, our way of starting to make sense of the world. It hasn’t dated a moment since its release, because it sounded like nothing else then, and that still stands today.

Defiantly cerebral and turning violence and ugliness into a strange type of beauty, The Holy Bible remains, 25 years on, the single most important British album of the 1990s. Amen.