The return of The Cure with brand new single Alone has prompted a resurgence of interest in the British goth icons. In 2004, founder and frontman Robert Smith spoke to Classic Rock’s Siân Llewellyn about the highs and lows of his band’s influential career.

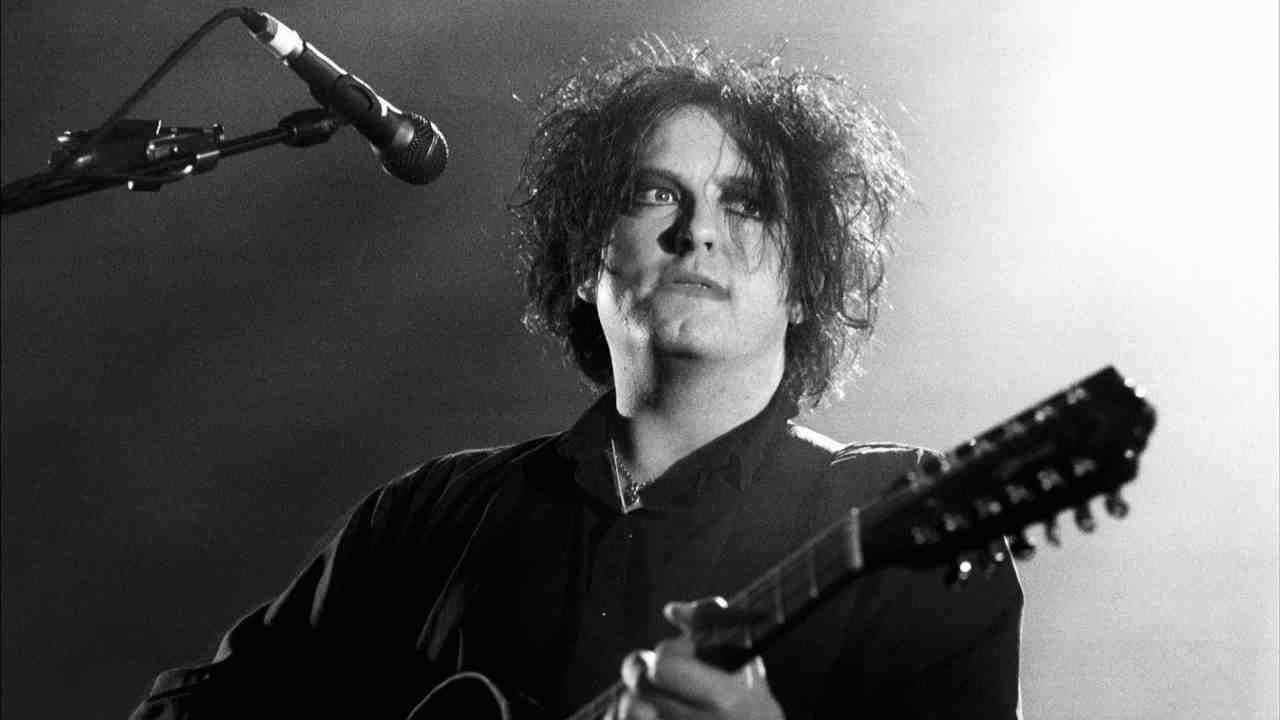

There’s never been a plan with The Cure,” says Robert Smith. It’s 2004 and the frontman of one the UK’s most successful bands is holding court at London’s Olympic Studios. Head to toe in black, hair wild but bereft of his trademark smeared lipstick, Smith’s a jovial sort, and the antithesis of the material on the albums he’s here to discuss.

Two decades after The Cure’s Pornography album burned itself into music fans’ consciousness, Smith found himself at a crossroads. His band’s most recent studio album, Wild Mood Swings – never before had an album been more accurately titled – had failed to set the world on fire. “For a number of reasons I had reached this point where I didn’t feel like I knew what I wanted to do, and I’d never really felt like that before,” Smith says. “I wondered if this is how it felt when it was it. When it was time to stop.”

It wasn’t, but it took a long look backwards to figure out the way forward. “I tried to think what people would like us to do,” he admits. “I was trying to second-guess what The Cure meant to people rather than just worry about how I felt about it, which I’d always just done before.”

And in this period of uncertainty, Smith returned to a pair of the bleakest albums in his catalogue. “I listened back to Pornography and Disintegration one particular weekend,” he continues. “I listened to them a couple of times each. I got very drunk. And got to thinking about what makes these records so special. They are always the two records that are brought up by fans of The Cure as being the ones that seem to symbolise everything they like about us. And for me as well, they are probably the two key albums that define The Cure, so I wanted something to follow that.”

The resulting album was 2000’s Bloodflowers, similar in tone and mood to the band’s bleak 80s material. It would also go on to become the final chapter in The Cure’s dark trilogy.

Pornography entered the pop landscape in May 1982, the same month that saw Barry Manilow’s Barry Live In Britain give way to McCartney’s saccharine Tug Of War at the top of the album charts. To say it sounded like nothing else was an understatement. Unrelenting and claustrophobic, it wasn’t above being panned upon release. Rolling Stone called it “the aural equivalent of a bad toothache”, but it mattered little. Cure fans, enthralled by the dark lyricism and minimalist sonic landscapes established on previous albums Faith and Seventeen Seconds, lapped it up. It ultimately it made Number Eight on the chart, The Cure’s most successful album to date.

Despite its success, the album session and resulting tour took its toll. As Smith and the others (the line-up then included the perennial Simon Gallup on bass and Smith’s childhood friend Lol Tolhurst on drums and keyboards) have freely admitted, recording Pornography wasn’t the most fun they’d had in the studio. The band was on the verge of splitting, as Smith told Rolling Stone in 2004: “During Pornography, the band was falling apart, because of the drinking and drugs. I was pretty seriously strung out a lot of the time, so I’m not sure if my recollection is right.”

With Phil Thornalley in the producer’s chair, the band set about making their artistic statement, as Smith said in the Pornography reissue: “I wanted to make the ultimate fuck-off record. And then The Cure could stop. Phil was trying to make it too nice… I wanted it to be virtually unbearable. I needed this recording to be our grand statement, and in the course of making it I didn’t much care about anything or anyone else in the world.”

Smith doesn’t have particularly happy memories of that time. “The band that did Pornography – me, Simon and Lol – that went out and played those songs the first time round… Well, I’ve got a few tapes of that tour and we really weren’t that good,” he admits. “It was an incredibly intense experience for us on stage. And at the time it was pretty depressing and I found it really, really difficult. We didn’t even get to America on the Pornography tour because the band disintegrated in Europe and me and Simon didn’t talk for well over a year. It was pretty fraught.”

Simon Gallup felt as though he was turning into someone else. “When we did the Pornography tour, it did change my personality,” he said. “I changed into somebody I didn’t like, I changed into a really nasty piece of work, but you can’t just blame it on the songs. It was of a time, and it was experimenting with things that by their very nature changed people’s personality.”

Following the charged, drug and alcohol-fuelled atmosphere of the Pornography tour, the situation between Smith and Gallup became untenable and the bassist quit. Instead of following the melancholic trajectory that his band seemed destined to follow, Smith regrouped (using producer Phil Thornalley on bass) and contrarily re-branded The Cure as a bona fide, radio and MTV-friendly pop act.

The disconcerting tour had served as conclusive proof that Smith had no real desire to be typecast as a prophet of misery. Returning to his parents’ home in Sussex, Smith began toying with the idea of a three-minute pop song. The result was a fledgling version of Let’s Go To Bed, which, when he took the demo to Fiction Records, was met with incredulity.

“They said, ‘You can’t be serious. Your fans are gonna hate it’,” Smith told journalist Bob Crandall. “I understood that, but I wanted to get rid of all that. I didn’t want that side of life anymore; I wanted to do something that’s really kind of cheerful. I thought, ‘This isn’t going to work. No one’s ever gonna buy into this. It’s so ludicrous that I’m gonna go from goth idol to pop star in three easy lessons.’”

But that’s exactly what did happen. The record company trusted Smith’s vision and the cheery pop single took hold on both sides of the Atlantic, confusing many new fans when they went to explore the band’s back catalogue. Smith, meanwhile, just found it all faintly hilarious.

His fanbase had changed almost overnight. “It went from intense, menacing, psychotic goths to people with perfect white teeth,” he says. “It was a very weird transition, but I enjoyed it. I thought it was really funny.”

But just as Smith had previously got bored of his doom mongering, after six years of pop stardom, he tired of the hedonistic Day-Glo pop hits. Smith (now with Simon Gallup back in the fold), became aware that he and his band had become everything he didn’t want to be: a huge stadium rock band.

“It sounds really bigheaded, but everyone wanted a piece of me,” Smith told Rolling Stone. “I was fighting against being a pop star, being expected to be larger than life all the time, and it really did my head in. I got really depressed, and I started doing drugs again – hallucinogenic drugs. When we were gonna make the album I decided I would be monk-like and not talk to anyone. It was a bit pretentious really, looking back, but I actually wanted an environment that was slightly unpleasant.”

Heading to the studio in Oxfordshire in November 1988, work commenced on Disintegration. It was quite the departure from 1987’s upbeat Kiss Me, Kiss Me, Kiss Me, but that didn’t stop the upward ascendancy of The Cure. When Disintegration was released in May 1989 fans latched on as easily to the sombre, atmospheric Pictures Of You, arachnophobia anthem Lullaby, and the plaintive Love Song (written by Smith as a wedding gift to his wife Mary as “a cheap present”), as they had to Just Like Heaven or The Love Cats.

Opening with Plainsong, and the eerie opening statement ‘I think it’s dark and it looks like rain’, Disintegration was not an easy ride, and Pictures Of You, with its washes of lush guitar and frankly unsettling lyrics, hit the same emotional buttons that Pornography had struck half a dozen years before. But while there are sonic parallels between Pornography and Disintegration, there are thematic differences. .

“I think they’re musically similar,” says Smith of Pornography’s One Hundred Years and Disintegration’s title track. “But lyrically it’s not similar at all because One Hundred Years is a kind of giving up, really. The meaning of the song is in the first line, ‘It doesn’t matter if we all die’. In Disintegration, it’s about getting away from someone, and in a weird way it’s more hopeful. One Hundred Years is about the upset of everything and Disintegration is just about the horrors of a relationship, so they’re different things. But musically I suppose there’s the same insistence in drum and bass.”

Shortly after the release of Disintegration The Cure took to the road again. Despite Smith’s distaste about being a “stadium rock band”, the tour was a resounding success and the new material gave the band a chance to stretch out and enjoy themselves. “Cure fans feel short-changed if we do anything less than two and a half hours,” says Smith. “We’ve done festivals where we’ve had to come off after 90 minutes and it’s just awful, cos we’re just getting into it. I think we’re heading towards a 12-hour spectacular if we’ve still got the stamina in another decade.”

But at that time “most of the relationships within the band and outside of the band fell apart,” said Smith. “Calling the album ‘Disintegration’ was kind of tempting fate, and fate retaliated. The family idea of the group really fell apart, too. It was the end of the golden period.”

It was also the end of the 1980s.

Disintegration had proved to be the perfect antidote to the larger-than-life, don’t-bore-us-get-to-the-chorus hair metal that was flooding the radio in the late 80s. Following that album’s commercial success, The Cure continued their dominance and released Wish in 1992, an album that perfectly married the pop band (Friday I’m In Love) to the epic soundscape outfit (From The Edge Of The Deep Green Sea). Then Smith’s contrary nature crept in, long-term drummer Boris Williams and Porl Thompson would call it a day, and The Cure would go on to release a series of idiosyncratic, good, though indistinct, albums. After a few years, The Cure needed to be reset. Smith rethought the band’s direction and the line-up.

“Trying to keep a band together just so everyone recognises the faces is really stupid,” laughs Smith, at the constant media assertion that The Cure is just him and an ever-revolving series of players. “It’s almost like worrying that no one’s gonna know who you are if you don’t have the same line-up. And it’s always been the case where I have been the most visible person in the band, for most of the time.”

But those who’ve come and gone have been largely the same faces: Simon Gallup has been the bassist continually, bar two to three years; guitarist Porl Thompson, who played from 2005-2010, was in The Cure while they were still in the demo-making stage; and keyboard player Roger O’Donnell was present for Disintegration, left and then returned for Wild Mood Swings.

That brings us to the late 90s. Seriously considering calling it a day while also trying to figure out what to do next, Robert Smith had something of a revelation while he was drunkenly listening to Pornography and Disintegration.

“I realised that I did Pornography when I was just turning 20 – well, I was just 21 – and I did Disintegration when I was just turning into a 30 year-old man,” he says. “I was now heading toward my 40th birthday, so I thought I should probably do something that is a third part of the story.

“When I was doing Disintegration I never imagined that it was a second part of a trilogy but, doing Bloodflowers, I said to the others to imagine something that would fit in with the theme of the other two albums, so it became a de facto trilogy.

“Pornography, Disintegration and Bloodflowers are thematically linked: they’re all very introspective albums; they’re very personal. But hopefully they transcend my own life, as is the hope of any good lyricist.”

Bloodflowers finally surfaced on Valentine’s Day in 2000, and while it was met with fair-to-good reviews, the record earned the band its only Grammy nomination – for Best Alternative Music Album of 2001 (though it lost out to to Radiohead’s Kid A). Smith still thinks it’s one of the best things The Cure will ever do.”

Upon rediscovering his sombre 80s muse, the frontman found that both Pornography and Disintegration were unwittingly encroaching upon The Cure’s Bloodflowers tour. “We found ourselves playing a lot of the older, heavier stuff,” he says. “It fitted in more with the mood of Bloodflowers.”

And that’s what lifted Smith’s hopes. “We hadn’t really done a tour like that for a long time, not since Disintegration, where we were playing really heavy sets,” Smith explains. I just thought it was really good fun and it was the best tour I’d ever done. I thought, ‘This isn’t the end of the group’, as I’d previously been thinking – I just had to re-find what it was I liked about being in it.”

Smith decided to make a defining statement, categorising Pornography, Disintegration and Bloodflowers as a dark trilogy. And when the Bloodflowers tour was over, it occurred to him to play all three in one night. Inspired after seeing David Bowie play one of his albums in its entirety – in the days before single album shows were de rigeur – he took his ambitious project to his band. “I suggested it to the others and they were a bit sceptical,” Smith says. But he won them over and The Cure played all three over two nights, in November 2002, at the Berlin Temprodom.

“It was conceived as a film. We thought, ‘If we’re gonna do it, then it’s going to be a one off,’” Smith remembers. “I wanted to capture the Bloodflowers look and feel of the band, because you never know with The Cure how long it’s going to last…”

The film was released as The Cure: Trilogy, (see left) and it leaves no doubt about the kinship of the three albums, sonically and emotionally. With their swirling guitars, dark lyrics and epic feel, they’re exhausting, yet brilliant – rock at its most harrowing and uplifting.

Robert Smith may not have had a plan for The Cure, but sometimes the best plans are the ones you never make.

Originally published in The Cure & The Story Of The Alternative 80s, August 2012