In 2005, Geoff Barton’s Classic Rock cover story brought to light new information regarding Bon Scott’s movements the night he died, via interviews with former UFO members Pete Way and Paul Chapman.

In contrast with the widely reported version of events, Paul claimed to have been visited at home by Bon and his friend Joe Fury before Bon left their company, going on to meet up with the mysterious figure Alistair Kinnear.

Bon Scott biographer Clinton Walker had concluded that the name Alistair Kinnear was most likely an alias and no such person ever really existed. But Kinnear was real, and the year the feature was published he surfaced and consented to an email interview. The interview, which came in the form of a statement, was later published in a Metal Hammer/Classic Rock AC/DC special. Some 12 years on, author Jesse Fink tracked down some more key figures to try to piece together what really happened that fateful night…

Bon Scott’s death is arguably to rock music what the JFK assassination is to American political history: the great unsolved mystery of our time. The players involved contradict each other, pieces of crucial information are missing, and very little of what has been presented as fact stands up to rigorous scrutiny; all of which fuels the various conspiracy theories.

Much of the generally accepted version of events has been built around the testimonies of Alistair Kinnear, Joe Fury and Silver Smith, three people all allegedly associated in some way with heroin; the tight-lipped members of AC/DC; and a Japanese girl, Anna Baba, who had only recently been dumped by Bon after a casual relationship that lasted less than four weeks and wasn’t actually with him on the night of his death.

Now, what I believe is the true story can be told. And it’s easy to tell it simply by deconstructing Alistair’s 2005 statement to friend and crosswords compiler Maggie Montalbano that ran in Metal Hammer & Classic Rock Present AC/DC. It began:

“In late 1978 I met Silver Smith, with whom I moved to a flat in Kensington. She was a sometime girlfriend of Bon Scott. Bon came to stay with us for two weeks, and he and I became friends. Silver returned to Australia for a year, and I moved to Overhill Road in East Dulwich. On the night of 18 February 1980, Xena [sic] Kakoulli, manager of The Only Ones, and wife of bandleader Peter Perrett, invited me to the inaugural gig of her sister’s band at The Music Machine in Camden Town (renamed Camden Palace in 1982).”

Peter Perrett and his wife of ten years, Xenoulla ‘Zena’ (alternately spelled as Xena) Kakoulli were good friends of Alistair, according to Silver: “They’d known each other forever. I only met Peter and his wife once, but I know they were very close.” They were also well known for their fondness of heroin.

In 2009, Perrett described to MOJO the London drug scene of the time: “In America I could spend $500 a day and not even get straight because the heroin was so weak. The street stuff there, it was between two and six per cent heroin because it had been controlled by the Mafia and organised crime for so long and that was how they cut it. That’s why so many American junkies OD’d when they came to England… We were awash in this Iranian brown heroin, on account of the rich Iranians fleeing their country, taking their money out in drugs. It was easier than smuggling gold.

“You see, in the 60s junkies got most of their stuff from doctors, pharmaceutical stuff, which isn’t the same. There was the occasional white heroin, which was from the Golden Triangle. That was normally quite weak, but there weren’t that many junkies around and there just wasn’t a black market in it. Plus you had to inject that stuff, and it seemed a big step to go from smoking a joint or snorting a bit of coke to sticking a needle in your arm. But with the brown heroin you could snort it, or just smoke it, and smoking it just seemed less threatening.”

But while injecting is by far and away the most lethal method of heroin administration, snorting and smoking also claim lives. A 2003 paper by researchers at the Karolinska Institutet in Stockholm found that of 239 heroin-related deaths in Stockholm from 1997 to 2000, 188 were from injecting, 33 were undetermined, 11 were from snorting and seven from smoking.

Of those 18 deaths from snorting or smoking, 83 per cent were male with a median age of 32. Five of the 18 were casual or ‘party users’. In eight cases there were eyewitnesses to the deaths. Three dropped dead immediately after smoking or snorting, “the other five fell asleep and were found dead later on”. The research team also found that factors such as alcohol and the presence of other drugs were “important” contributors to causing death from heroin overdose.

Brown heroin burns at a lower temperature than white heroin, hence it being used for smoking. In London in early 1980, the in-thing was to smoke or snort brown heroin.

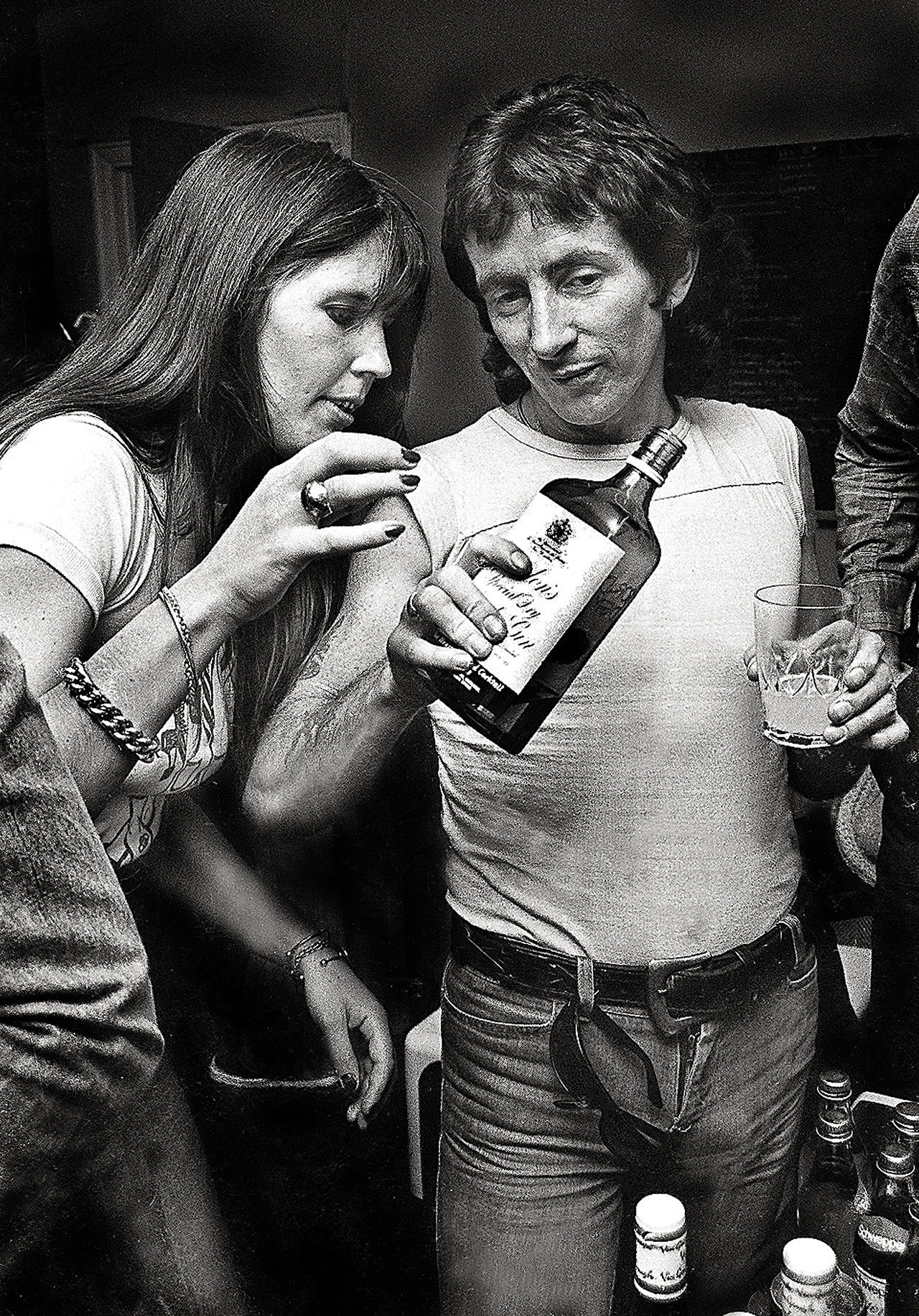

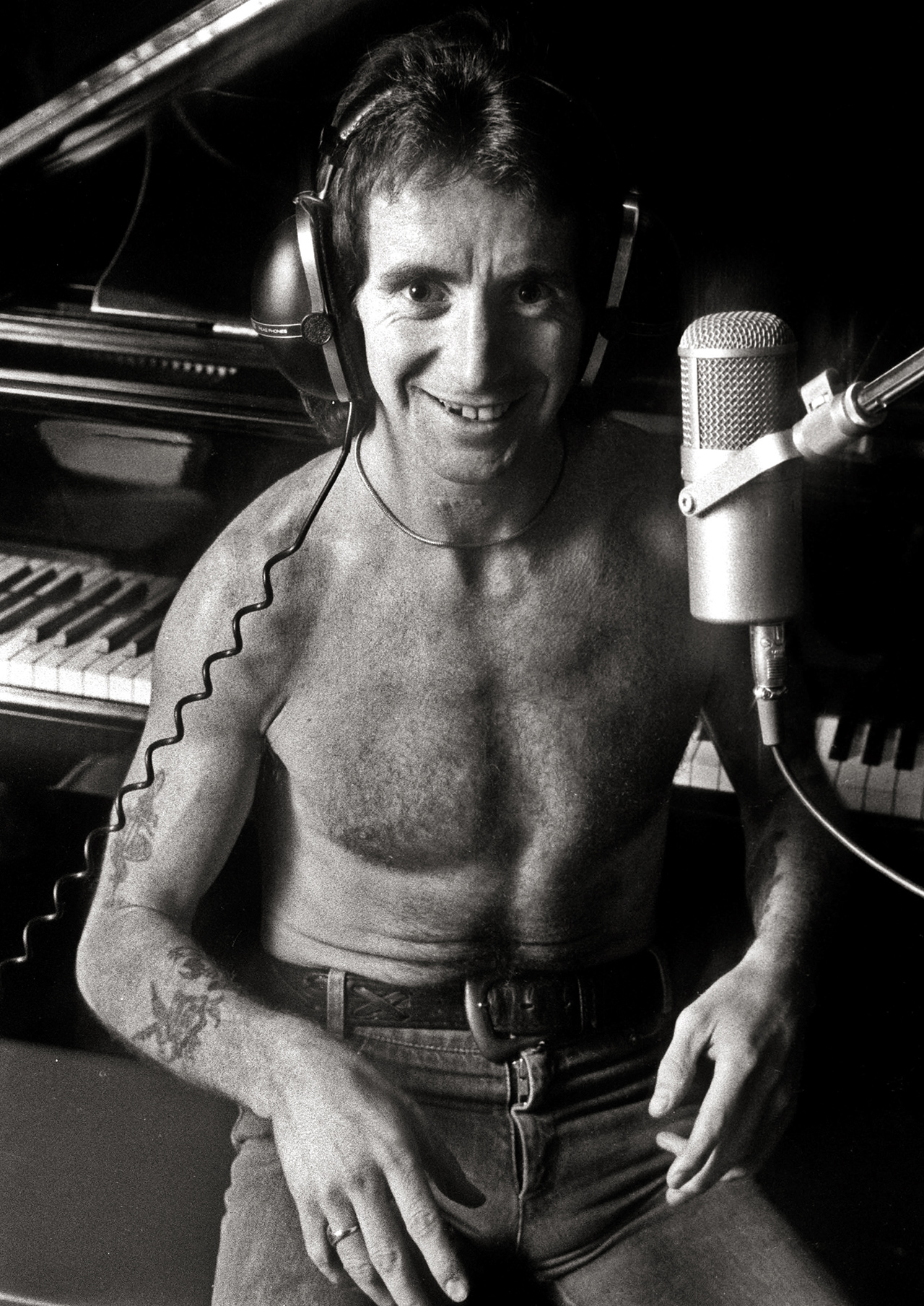

Says Paul Chapman of UFO: “In America, heroin was taboo at the time. So you get back to London, the first thing you do would be to dial up somebody you knew that had a bit of it. I was thinking, ‘[Bon’s] only just got here… if he hadn’t connected [with heroin] already, if everybody around him is doing this, I’m surprised that he’s not, you know, partaking like everybody else.’”

Silver told me that the heroin trade in London in 1980 was “a hippie thing on a small scale. It was very small scale. The importation was a couple of ounces at a time; it wasn’t sort of organised bloody container loads.”

Users in London mostly sought brown heroin to snort it, and she snorted herself, as did most of her friends and acquaintances. A few others smoked it, but she “never saw a needle, never saw a gun, nothing like that, there was nothing sordid”.

“A few travellers would bring in what was called ‘Thai white’ or ‘China white’. [Heroin dealing] wasn’t a disreputable occupation at the time. You had to have a few things going for you. You know, discretion. That was another thing. Bon was horribly indiscreet. He just didn’t think about things.”

Alistair’s story went on:

“I phoned Silver, who was once again living in London, to see if she wanted to come along, but she’d made other arrangements for the evening. However, she suggested that Bon might be interested, as he had phoned her earlier looking for something to do. I gave him a call, and he was agreeable, and I picked him up at his flat on Ashley Court in Westminster.”

This is where things get problematic because Alistair’s version of events clashes with Silver’s. Silver lived not in a flat in Gloucester Road, Kensington, as widely believed, but in what she described as a “tiny attic” in Emperor’s Gate, South Kensington, about a 20-minute drive from Bon’s flat at Ashley Court, Victoria. And from where Alistair lived in Overhill Road, East Dulwich, it’s roughly a 40-minute drive to Emperor’s Gate.

Silver told Australia’s ABC Adelaide in 2010 that on the evening of 18 February 1980 Alistair was planning to visit. When Bon called at around 7.30 pm asking her to go out, she declined, having already made plans, and suggested that he hook up with Alistair. Bon wanted to go to the club Dingwalls in Camden Lock.

Silver said she told Bon: “Alistair’s coming over later, do you want me to get him to ring you? He might go with you.” And that’s what happened. They set off together.

Yet in the original 1994 edition of Australian author Clinton Walker’s biography of Bon, Highway To Hell, she described another scenario altogether: Alistair was already in her flat when Bon called. She said: “Oh, Alistair’s here, I’ll see if he wants to go.”

How did those details come to change so dramatically in 16 years? Why was there no mention whatsoever of Joe Fury sharing her flat, as he claimed when I interviewed him?

Alistair and Bon were quite the odd couple but they knew each other well and were friends. Silver told me the pair had first met years before at the flat she was then occupying in Abingdon Villas, Kensington. Alistair even moved in with them for a period. On this detail, Alistair’s statement to Montalbano is substantiated: “He actually stayed with us, Bon and I, for a couple of months because he had work up in the city.”

After that, they lost contact, but “the night that Bon died, we hadn’t seen him in quite a while”.

Adding some weight to Alistair’s claim that he knew Bon, Clinton Walker’s book established that Anna Baba called Alistair after Bon’s death. She had his number. It appears with his name on the inside back cover of a pocket book allegedly owned by Bon but in Anna’s possession.

“When I saw him at the flat, [Bon] was already so drunk,” Anna quotes Alistair as telling her. In a short interview with London’s Evening Standard in 1980 Alistair said the same thing: “[Bon] was pretty drunk when I picked him up.”

So it’s odd that Alistair makes no mention at all in his statement to Montalbano of Bon being drunk when he arrived sometime between 11pm and midnight at Bon’s flat.

Joe Fury thinks it was out of character for Bon to be drunk at home so early in the evening: “I found it a bit funny… [it was] unusual for [Bon]. He must have been pretty damn drunk when Alistair picked him up [for Alistair] to say that Bon was drunk, ’cause he could drink a bit and you wouldn’t really know it.”

In an interview with a Canadian podcast, Colin Burgess, AC/DC’s first drummer, said he and his musician brother Denny may have been at The Music Machine that night, though he conceded, “I’m not sure… we went there with Bon… I can’t remember; it was a long time ago.” He’s on the record elsewhere as saying Bon didn’t appear intoxicated: “Bon was sober… I cannot remember Bon being drunk enough to kill himself in a car. I mean, come on.”

Yet, if we are to accept Alistair’s earlier comments, Bon was already drunk and got drunker as the night went on, reputedly drinking seven double whiskies.

“It was a great party, and Bon and I both drank far too much, both at the free bar backstage and at the upstairs bar as well; however I did not see him take any drugs that evening.”

Not seeing him take drugs is different from him not taking drugs. Lonesome No More was the band playing that night. Lead singer Koulla Kakoulli, sister of Zena, had done backing vocal work for both solo artist Johnny Thunders and Peter Perrett’s new band, The Only Ones, in 1978. Contrary to some reports, future guitarist for The Cult, Billy Duffy, wasn’t playing guitar that night with Lonesome No More – but he was there at the club.

“It’s very simple,” says Duffy. “I had been invited down to watch Lonesome No More play that night with a view to I think replacing the guitarist, which eventually happened, but I don’t think at that point I played with them.

“I was at the side-stage bar at the venue and I remember seeing Bon and another guy walk by, probably grab a drink at the bar and then disappear backstage. That’s it, really. I had seen AC/DC play in Manchester a couple of years previously and was a huge fan so there was no mistaking Bon.”

“At the end of the party I offered to drive him home. As we approached his flat, I realised that Bon had drifted into unconsciousness. I left him in my car and rang his doorbell, but his current live-in girlfriend didn’t answer. I took Bon’s keys and let myself into the flat, but no-one was at home. I was unable to wake Bon, so I rang Silver for advice. She said that he passed out quite frequently, and that it was best just to leave him to sleep it off.”

Again, Alistair’s account is at odds with Silver’s. Silver said that “the keys got jammed inside the door” while Alistair was attempting to enter Bon’s flat. Alistair makes no mention of this.

“According to Silver, when they got to Ashley Court, Kinnear couldn’t move Bon,” wrote Walker. “He roused him, but Bon couldn’t, or wouldn’t, move. Thinking he could usher him inside if he cleared a path, Kinnear took Bon’s keys and opened the flat, leaving the door ajar. The building’s front door, however, presented Kinnear with something of a problem, and although he managed to open it, he subsequently locked himself out.”

The keys jammed, or he locked himself out? It’s another inconsistency made more puzzling by the fact that the important factor of Bon’s house keys isn’t referenced in Alistair’s statement to Montalbano. As for the phone call, why would Alistair be ringing Silver asking for “advice” when he was already inside Bon’s fourth-floor flat, #15, and a natural course of action would be to carry him upstairs or at the very least attempt to do so?

He’d already driven drunk, by his own admission, from The Music Machine. How hard could it be to throw an arm around Bon’s waist and try to get him inside? Silver said she got the call from “a very distressed Alistair” around 1am, saying: “He’s passed out. He’s half passed out. What do I do?”

It wasn’t uncommon for Bon to drift off into a stupor from alcohol so, again, why would Alistair call Silver in such a panic from inside Bon’s flat if he thought it was just alcoholic intoxication?

“I suggested he take him home [to Alistair’s flat in East Dulwich],” said Silver, “where he might be able to get some help to get him up the stairs.”

Or in other words, she was suggesting to an intoxicated Alistair, who had the passed-out lead singer of AC/DC in his car, that he travel twice as far as he needed to, rather than drive the shorter distance to her flat in Emperor’s Gate, where she (and Joe, whom she failed to mention was there) could conceivably be of at least some assistance.

“I was up five flights, he was up three, so that seemed sensible, ’cause I was six-and-a-half stone and used to wear four-inch heels… I’d been in that situation with Bon many times and it was difficult, believe me.”

Whose help exactly was Alistair going to get at that time of the morning? Why couldn’t Silver get help from Joe or offer Alistair a hand herself? Why hadn’t Alistair called his own father, Angus, a doctor who lived in Forest Hill, next to East Dulwich, if he was worried about Bon’s health and didn’t want to go to a hospital? He lived only a mile from Alistair’s apartment.

Today Joe is genuinely regretful he didn’t help Alistair, talking of “my own guilt that I hadn’t gone out with [Bon] that night and tried to keep an eye on things… this is where you take a lot of ‘if only’. If only I’d gone to help Alistair try and get [Bon] into his own flat.”

He thinks that if Alistair had in fact lost Bon’s keys he was concerned at the time with the question of “Where will I take him back to if I can’t get into his flat?” This is perhaps understandable, if Joe was with Silver in a tiny apartment containing one bed and not much else. But “after so many occasions [of seeing Bon passed out] you just sort of think, ‘Oh, it’s another night out. Sleep it off in the car.’”

Joe says his reaction that night to Alistair’s call for help might have been different “if Bon had been in reasonable condition, [if] he hadn’t been drunk all the time”.

The guilt lingers to this day even if the memories of that fateful morning remain foggy.

“I felt indebted a bit to Bon because he’d always been very generous [to me]. Later I was thinking, ‘Well, shit, he rang and said, “Do you want to go out?” I should have said, “Yep.’” If I had gone out with him then I would have got him [inside], sorta got him home. When Alistair called, maybe I should have said, ‘Okay stay there, I’ll come down’ or ‘Bring him back here’ or something like that, which makes me think I was probably at Silver’s place.”

Were Bon’s story a TV whodunnit, a natural deduction to make at this point is that Bon was possibly already dead. Is that why Alistair was calling Silver in a blind panic? Had he told Silver and Joe the whole truth of what was going on? A man in such a predicament might have thought that leaving Bon’s keys inside his flat would make it look like Bon had been there; that he’d stopped by to collect something and gone somewhere else.

We know from Walker’s book that the caretaker at Ashley Court left a note behind for Bon on the 19th, saying a set of keys had been found on the mat inside the front door, the door of the flat was open, and all the lights and radios were left on.

But why would they be left on? Turning on a radio is not the first thing you do in the early hours of the morning while attempting to carry a passed-out friend to their bedroom or bathroom, unless you’re trying to wake them up.

“I then drove to my flat on Overhill Road and tried to lift him out of the car, but he was too heavy for me to carry in my intoxicated state, so I put the front passenger seat back so that he could lie flat, covered him with a blanket, left a note with my address and phone number on it, and staggered upstairs to bed.”

I propose to Paul Chapman that Bon may have already been dead, Alistair panicked, and made the decision to leave Bon’s body in the car to make it look like he died of natural causes during the night. At 67 Overhill Road, there were only six flats. Alistair’s one-bedroom flat was on the top floor, #6. It really wouldn’t have taken a huge effort to get Bon up the stairs and inside.

“Surely somebody wouldn’t just leave him there? Wow. I’ve never thought of that. Now that’s just opened up a whole new thing in my head. Who would do that? Somebody must have been extremely out of it upstairs, wherever upstairs was, and forgotten Bon was in the car. I remember how cold it was at my flat when the Calor gas went out, let alone being in a car outside. Whoever was down there with Bon in [East] Dulwich must have been upstairs nodding out. That’s the only thing I can think of. I cannot believe that somebody would not go out and check on him in that weather.”

Chapman mentions the weather and it’s worth elaborating upon. There are sundry misleading stories of Bon dying from hypothermia or freezing to death.

I checked with the Met Office. Temperatures that morning of 19 February 1980 didn’t get colder than five degrees Celsius. Both the 18th and 19th were dry days with slightly above average temperatures. So there was no frost.

The air temperature wasn’t that cold, then, for Bon to freeze to death. He wasn’t exposed to wind. It wasn’t raining. Bon was clothed, dry and, according to Alistair, had a blanket, possibly two. Hypothermia typically occurs after exposure to a combination of wind, water and cold air, or at least two of those factors. And while alcohol and drugs can reduce body temperature and exposure to cold air can bring on an asthma attack, Bon would have had to be especially unlucky to perish from hypothermia when he was dry, protected from the wind in an airtight space, and the temperature was “above average”.

On the balance of probabilities and with all the available evidence, there’s very little to show that Bon died from hypothermia but plenty to suggest he perished from something else.

Now at this critical point in the story Alistair Kinnear is, by his own admission, “intoxicated”. Yet despite his supposed drunkenness, he’s just driven his Renault 5 for 11 miles across London from Kings Cross/Camden via Victoria/Westminster to East Dulwich. According to Silver Smith he made a phone call at 1am from Victoria. Alistair doesn’t mention another phone call to Silver in his statement to Maggie Montalbano, yet both Silver and Joe Fury previously claimed in interviews that there was a second phone call.

Silver denied there was ever any collusion between her and Joe in their accounts of the morning Alistair phoned. Joe certainly is adamant he was not with Paul Chapman in Fulham.

According to Silver: “By the time [Alistair] got [to East Dulwich] Bon had just completely passed out; [Alistair] couldn’t even get him out [of] the car.”

Joe estimated that the second phone call came at 3am. That is a full two hours after Alistair’s first call to Silver. A car journey of 11 miles at 1am across London shouldn’t take very long. What was Alistair doing between Victoria/Westminster and East Dulwich that would take two hours? Attempting to resuscitate a dying or even dead Bon?

Recalled Silver for Australian ABC radio: “When [Alistair] got home he rang me again and said, ‘[Bon’s] down in the car, I can’t get him up here.’ So I said [to Alistair], ‘Well, take down some blankets.’”

Speaking to me, she rubbished the idea that she should have contacted the AC/DC camp immediately after Alistair got off the phone.

“People think, you know, it’s like today where everyone’s got Facebook, everyone’s got their bloody mobile with them every minute of every day. It wasn’t like that.”

Even if she’d had their numbers, which she didn’t, she thought she would have been ignored had she called the Youngs and told them Bon had passed out. “If I’d rung Malcolm and Angus and said, ‘Oh, listen, Bon’s passed out in a car in South London at two o’clock [sic] in the morning’, they would have just gone, ‘What the fuck are you telling me for?’ It was like, well, what’s new?”

Joe holds a similar view: “Four o’clock [sic] in the morning and someone’s having to take care of Bon, again. When I first met Silver, and I’m talking about her in relation to Bon, there was a lot of that [with Bon]. It all sounds good. But he was hard, very hard work in terms of passing out on you somewhere, which is partly why the relationship between me and her sort of developed a bit. She [wanted] someone a bit more organised, a bit more together.”

“The other thing,” Silver continued, “is if everybody rang an ambulance and moved their friend to hospital, everyone that ever passed out on alcohol, we’d need a bloody big ambulance service and also an expansion of the hospital system. That’s just stupid. That’s the sort of thing, you think, ‘Well, shit. Are you kidding?’ I would have thought it would be logical.

“I mean, how many times have you had friends pass out on alcohol, especially when you were young? You don’t ring an ambulance and get them to hospital. They wouldn’t thank you for it in the morning. Bon did that all the time. All the time. He didn’t ever think how it was going to be for the people around him. Ever. He just did.”

However, despite Silver’s legitimate protestations, it’s concerning that by her own account she got two phone calls from Alistair, quite panicked ones, and never thought the entire day of the 19th to either call Alistair to see how Bon was or try to call Bon herself or send someone around to Alistair’s flat to check on both of them.

Then there is the issue of the blanket or blankets. Silver told me Alistair “took down pillows and blankets”.

“I don’t think there was a blanket,” says Chapman. “I don’t think there was anything. Whoever left him in the car probably left him in there thinking that they weren’t going to be very long.”

Were there no blankets at all, then hypothermia would be possible.

“You see what I mean? ‘Oh, we’ll be out in a minute. Oh, look, he’s passed out. Leave him there for a minute.’ Then next thing you know they go in, whoever they are… and they probably went, ‘Oh, give us a bit of that.’ And they do a bit of that. And the first thing that happens is you put your head [down], bang, and you go, ‘Oh, that’s great.’ And then you nod off. I think whoever went with Bon to Dulwich sampled some of what it was they were getting, which is exactly what I would have done.”

Chapman has been thinking about Bon’s death for some time.

“I’m burned on this. When I say I’m burned on it, it’s just that I can’t dig in any more corners and nooks and crannies in my brain.” He pauses for a moment. “After this happened [with Bon passing away], I went into my dealer’s and there was someone there who shouldn’t have been there.” Chapman names that someone. It was another member of AC/DC and he was buying heroin.

“He went, ‘[Expressing horror] Herrrhhh, Tonka! Whhhssshhh. I gotta go.’ And he was out the door. I was like [to the dealer], ‘I didn’t know you knew…’”

UFO bass player Pete Way says the same band member later pulled a shotgun on a former member of AC/DC who’d paid him an unexpected house visit.

“He was running off the rails. He was very wired and in a bit of a state and he had a shotgun… really, like, in a condition. The guy only came out to say hello and he didn’t expect to be greeted by a shotgun. A lot of things were going on around then that should never have been going on.”

According to Silver, Alistair left a note with his address inside the car for Bon, “thinking when Bon’s come out of it he’ll just come upstairs”.

Said Alistair:

“It must have been 4 or 5 am by that time, and I slept until about 11 when I was awakened by a friend, Leslie Loads. I was so hungover that I asked Leslie to do me a favour of checking on Bon. He did so, and returned to tell me my car was empty, so I went back to sleep, assuming that Bon had awoken and taken a taxi home.”

This is the most perplexing part of Alistair’s statement. Who is Leslie Loads? No Loads has ever been interviewed or spoken publicly about the day Bon died, which surely would have happened by now – unless Loads, as I suspect, was a pseudonym.

“Poor Alistair, not being used to drinking, woke up the next morning with a terrible hangover and decided not to go to work, went back to bed,” Silver told Australia’s ABC in that same 2010 radio interview. “And when he got out later, which was like mid-afternoon, there was poor Bon still in the car.”

Alistair was working where exactly? Silver said “he was working a lot in Central London” but could not recall what he was doing at the time of Bon’s death.

But Alistair’s son Daniel Kinnear tells me he and his mother Mo “had zero financial support from my father”, grew up in a “very deprived household” and “were supported by government benefits and from additional money that my mother earned via cleaning jobs in pubs or other people’s houses”.

So the idea of Alistair being gainfully employed in a day job sounds most unlikely. Just as unlikely as mystery figure Loads going down to the car and seeing it empty. A comatose man in two blankets would surely be spotted even if he were stretched out asleep on the back seat or lying on a semi-flattened front seat. In their version of events, Way and Chapman were also informed Bon was dead well before Loads supposedly went down to Alistair’s car and found nothing inside.

The introduction of Loads into Alistair’s story just doesn’t seem plausible on any level. Was Alistair trying to give himself some sort of alibi, to make it look like Bon had momentarily left the car to go somewhere else? Was Loads there all along but not wanting to be identified? Was he even a he?

For the first time, I can reveal the identity of a third person that was with Bon and Alistair in East Dulwich on the morning of 19 February 1980.

The admission came during an exchange of online messages in late 2015.

“I was there when he died, as I spent the night at Alistair’s flat,” says Zena Kakoulli, Peter Perrett’s wife and the manager of The Only Ones. “I don’t know why [I stayed there], as I lived not far from him. Alistair had met Bon before that night; it wasn’t the first time they met.”

This totally corroborates what Alistair and Silver said about Alistair’s friendship with Bon: they weren’t strangers.

You were asleep in Alistair’s flat when Bon was in the car?

“Yes.”

Did you go back with Bon and Alistair in Alistair’s car to East Dulwich? Or did you arrive later? Was Peter Perrett with you?

“I went back with Alistair and [Bon] to Alistair’s flat. It was very late when we got back and I remember it being very cold. Peter did not go with us that night… Alistair was a close friend; the last time I saw Alistair was a few days before he went to sea [in 2006] and unfortunately disappeared… I met Bon Scott that night as Alistair was friends with Silver and I think knew Bon through her. It is a sad memory that still haunts me.”

So was Bon left in the car because you couldn’t both carry him? Was he still alive when you went inside? Do you know if he took heroin? I’m only interested in establishing the truth.

She’s selective in her answer, ignoring my first two questions, but reveals more than I was expecting.

“I didn’t see him taking heroin, but both Alistair and Silver were users at the time. I would think it probable that [Bon] did take heroin as I would not have thought somebody that was used to drinking would have been sick. It’s well known that if you take heroin when you have been drinking, especially if you don’t normally, it could lead to you vomiting, plus cause you to pass out. But I can only presume that’s what caused him to fall asleep and later vomit. He didn’t seem unreasonably intoxicated.

“If he had taken heroin it was with Silver and Alistair at the venue; I didn’t see him [take heroin]. Unfortunately the only persons that can know for sure are Silver and Alistair. I know how devastated Alistair was, and how it affected him for years afterwards. It is so bad that we will never know what happened to Alistair. He was such a lovely guy, and his disappearance has left an unsettling feeling. I miss him.”

It’s a mind-blowing admission after nearly 40 years of silence for a multitude of reasons. Zena was with Bon and Alistair in East Dulwich all along, rendering illogical the explanations proffered by Alistair, Silver and Joe about why Bon was left in the car, though there is no evidence Silver or Joe knew she was with Alistair.

According to Zena’s account, two able-bodied people were in the car with Bon – herself and Alistair. They could have carried him inside to either Silver’s flat (with Silver’s and Joe’s assistance, were he there, as he claims) or Alistair’s flat (on their own). Why didn’t Zena offer to help Alistair? Did she offer to help? Why didn’t Alistair take Bon to the hospital when Zena described him as being “sick” and having vomited, surely a possible sign of a heroin overdose, especially so given the company he was in at The Music Machine? If Alistair truly thought he was just dealing with a case of drunkenness, then why bother to phone Silver? Who calls and wakes up someone both at 1am and 3am if it’s not an emergency? The conventional telling of Bon’s demise – Silver’s, Joe’s and Alistair’s – just gets blown to smithereens.

I attempted to contact Zena for a series of follow-up questions to clarify some of the things she said, but my messages went unanswered. Yet she left me with enough information to convince me Bon had succumbed to a fatal heroin overdose and it had effectively been covered up.

A former heroin user now afflicted with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), a condition that has been widely linked in scientific literature to heroin inhalation, Zena thinks it was “probable” that Bon took heroin. She was there when Bon passed out and believes he hadn’t consumed enough alcohol to become unconscious. She confirms there was vomit, though whether she witnessed that herself or is basing her statement on media reports is unclear. Sensationally, she also suggests that Silver was actually at the venue with Alistair and Bon, which again fatally undermines the commonly accepted story as put forward in Walker’s book. But, again, there is no evidence Silver was at The Music Machine. If she was, she never admitted it while she was alive.

Zena’s sister Koulla Kakoulli of Lonesome No More also saw Bon in the last hours of his life: “[Bon] had so much to live for. Yes, he did come to our gig. If I remember right he was found in his car the next morning. Alistair was with him most of the night.”

So you knew Alistair? Were they drinking, doing drugs?

“I don’t think I should say. All I can say is Alistair was heavily into heroin at the time of Bon’s death. I know [Bon] was dead in the car outside.”

Heavily. An individual who was at The Music Machine that night and performed on stage doesn’t want to be quoted publicly but drops another bombshell: “Bon had a lot to drink that night. And I would be very surprised if he too [like Alistair] didn’t take a lot of drugs that evening, mainly heroin. I don’t wanna upset anybody this late in the game. End of the day it was a tragic accident. But [speaking] as an ex-junkie, Bon looked stoned.”

To be clear, the inference being made isn’t to getting high on marijuana. The inference is to heroin.

This is an abridged, edited extract of Bon: The Last Highway by Jesse Fink, out now through Black & White Publishing.

Who is Joe Fury?

Joe Fury operated – or at least was known by or has been referred to – under various aliases: Joe King, Joe Silver, Joe Furey and more. In written correspondence with me, Silver Smith frequently referred to him as ‘Jou’.

Just like Alistair Kinnear, the reclusive even apocryphal Joe has become a sort of bogeyman in the Bon Scott story. In three years of writing Bon, information about him was very hard to come by. I could only gather that on his return to Australia from living abroad in the early 1980s, Joe played bass in various bands and later gigged regularly with a band in Sydney called Rough Justice. He got married, moved on and fell off the radar. No one I spoke to who knew Joe or “Joey” could remember his real last name – or wanted to tell me.

Then, in September 2016, I had a breakthrough and finally made contact with Joe. Today he runs a garage business in New South Wales, but in the late 70s and early 80s he was a backstage fixture in the international live-music scene, working as a roadie for UFO, Wild Horses and even Little River Band.

Of Italian heritage, his real name is Joe Furi. He told me his “original family background was not terribly enjoyable”, which was partly why he changed his name to Fury.

Joe said he never read Clinton Walker’s book nor Geoff Barton’s Classic Rock article containing the allegations made about him by Paul Chapman. He wasn’t impressed: “It’s the greatest amount of drivel and crap I’ve ever read… I don’t know where [Barton] is now, but if he’d said that [to me] at the time he would have got a smack in the fucking head.”

He wasn’t even aware suggestions had been made that he was Alistair Kinnear. He knew nothing of Alistair’s 2005 statement to the press. Astonishingly, he was totally oblivious to the fact that Alistair was dead.

As Joe put it drily, he’d been occupied with “other things than following late 70s rock’n’roll”.

Bon and Joe had become friends back in Sydney in early 1978. When soon afterwards Bon and Silver broke up/took a 12-month break from each other, she and Joe travelled overland through Asia.

Bon, says Joe, “didn’t really want her heading off on her own”, so Joe accompanied Silver with his friend’s blessing. Bon even paid for Joe’s ticket.

It was during this trip that Joe and Silver would become intimately involved. On arriving in London, they worked together at the Tudor Rose, a pub in Richmond, and shared a single-room flat nearby, where Bon visited them. Yet Silver denied that she was in a relationship with Joe when Bon died.

“People quite reasonably kind of assume that [Joe and I] were [in a relationship]. We were just incredibly alike. Like twins… we just really hit it off; we had a lot of interests in common as well, quite esoteric stuff.”

But Joe tells a different story. He says he and Silver had formed “an unusual relationship” where they’d “merged into a bit of an entity”. Bon well knew what was going on between them yet didn’t feel threatened by it because, as Joe puts it, the affair was nothing more “than me sort of treading water with her until Bon finished up with AC/DC”. He presented “no challenge to Bon and Silver being the couple”.

“Friends of mine said, ‘What the fuck are you doing, you’re going to get killed. You’re screwing AC/DC’s lead singer’s fucking girlfriend. How long do you expect to live [laughs]?’ Looking back on it a couple of years later [after his death], I thought, ‘Jeez, I’m surprised he didn’t fucking hit me over the head with a baseball bat’ [laughs].”

Silver, says Joe, was Bon’s true soulmate, the woman with whom he might have returned to Australia to settle down.

“If you saw the two [of them] together, they were like an old couple even back then when they weren’t very old. Bon almost had the slippers and the pipe out and she’d be making him a cup of tea. It was that sort of relationship. It had none of that rock hysteria, fucking fame, showbiz [element to it], anything at all. Bon could have been out mowing the lawn and fixing things in the shed and she would have been saying, ‘The scones are ready.’”

As for a long-standing rumour that Malcolm Young had Joe beaten up after Bon’s death, for reasons unknown, it never happened. In fact, neither Joe nor Silver would ever cross paths with AC/DC again.

“It wasn’t Joe that was the problem between me and Bon,” deadpanned Silver.

So Bon’s problem essentially was Bon?

“Yeah,”’ she replied with a raspy laugh.

Exclusive: AC/DC's Bon Scott died from drug overdose, claims new book